The war for democracy and democracy in war

The third year of Russia's full-scale invasion had begun. Ukraine was supposed to hold presidential elections in one month, and the new parliament was supposed to be settling in after being elected in October. Instead, democracy researchers note that Volodymyr Zelenskyy is increasingly concentrating power in his hands.

In 2022, Ukraine has clearly shown that it continues implementing reforms and is shifting its focus towards the West. The state policy is clear: the war with Russia is not only a matter of survival but also of global values, and Ukraine is on the side of democracy. Domestically, martial law still imposes restrictions on citizens, but how to balance them with security measures, and whether there are any algorithms for how to act.

This article was published as part of the special project 'The War Continues: A History of Ten Years of Resistance'.

An excursion into the history of Ukrainian independence

The first Article of the main law of Ukraine, the Constitution, states: "Ukraine is a sovereign and independent, democratic, social and law-based state".

In 1991, the vast majority of Ukrainians voted in favour of independence in a referendum. However, a communist, Leonid Kravchuk, who had been the chairman of the Verkhovna Rada of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, was elected president. The country was slowly moving away from the Soviet system, becoming more independent and looking more boldly to the West.

The era of the late Leonid Kuchma is remembered for the rise of the oligarchs and the murder of the journalist and founder of Ukrainska Pravda, Georgiy Gongadze. Records later emerged suggesting that Leonid Kuchma may have ordered the murder. In 2013, the court ruled that the recordings could not be used as evidence. Kuchma did not bear any responsibility for this.

In a conversation with Svidomi, the current chairman of the Verkhovna Rada Committee on Freedom of Speech, a historian by training, Yaroslav Yurchyshyn, calls this period one of the most difficult in the context of media work. No other president in Ukraine has ever been elected twice.

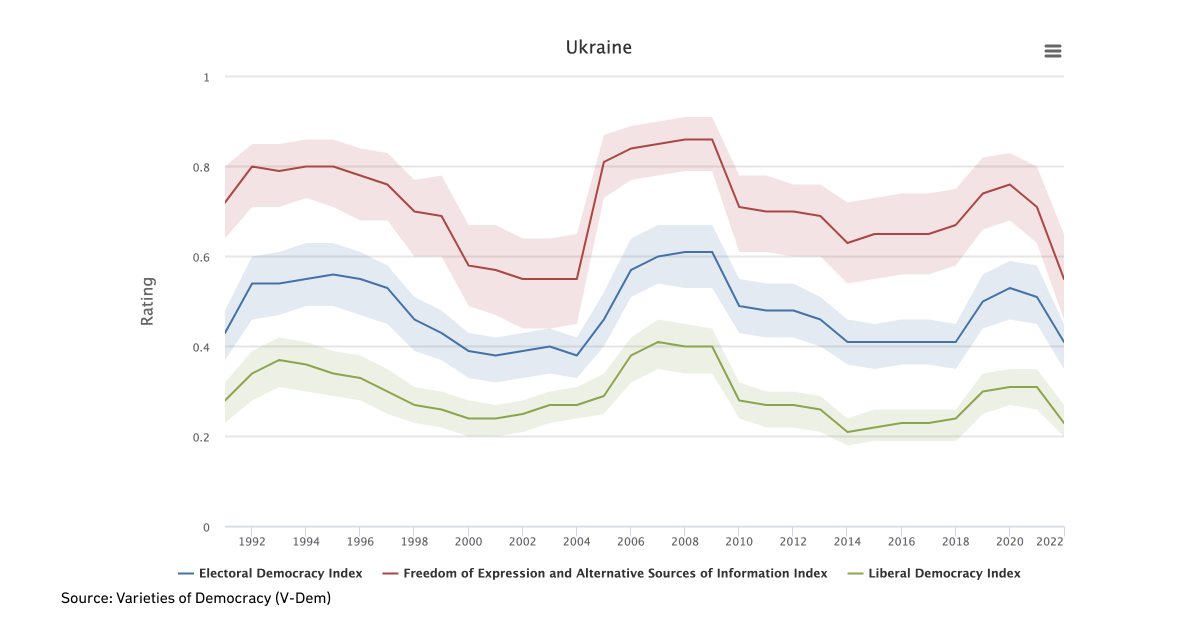

The Orange Revolution of 2004 clearly showed the preferences of the public: fair elections and a democratic system (the revolution occurred due to fraud in the presidential election, which led to a third round of voting. As a result, Viktor Yushchenko became President of Ukraine, not Viktor Yanukovych, who "won" the second round of elections. Yanukovych became President in 2010 and fled to Russia in 2014 – ed.). Under the presidency of the more Western-oriented Viktor Yushchenko, Ukraine entered the top 50 countries with a democracy index of 6.94 out of 10. The head of the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine, Serhii Tomilenko, said that the highest index of freedom of speech — 67% — was in 2009, the last year of Yushchenko's presidency.

The indicators declined in 2010 when pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovych was elected president. Ukraine has constitutionally reverted to a presidential-parliamentary form of government.

The Economist Intelligence Unit, which measures democracy around the world, describes this period as a rollback of democratic gains and the persistence of corruption in the oligarchic clan system that controlled politicians and the media. "Ukraine had many of the formal institutions and features of a democracy, but beneath the façade there was little substance," the organisation's report says.

The Euromaidan and the Revolution of Dignity of 2013-2014 were direct messages to the people that authoritarianism and decision-making that contradicted public sentiment would not work in Ukraine.

American researcher Emily Channell-Justice, director of the Temerty Contemporary Ukraine programme at Harvard University's Ukrainian Research Institute, has written a book about political activism and self-organisation on the Maidan.

Ukrainians have a strong belief in their own ability to change things. People didn't wait to vote Yanukovych out of office. They decided to go into the streets and tell him to get out. That's not exactly democratic, but it also shows the power of the voice of ordinary citizens,

Emily Channell-Justice tells Svidomi.

She notes that the process of Ukraine's transition from a post-Soviet country to one that, unlike Russia and Belarus, is trying to build a democracy has been gradual and has been getting stronger and stronger.

"It's not like Ukrainians woke up one day in 2014 and said, like, let's be part of Europe. I would describe it as waves that always get stronger. In 2004 and 2007, the European Union expanded to include other former early communist or socialist countries. That was a key point for Ukraine to recognise this as a possibility. And Euromaidan was like a final point — this is not even a discussion anymore, this is what we want."

After 2014, Ukraine gradually implemented reforms to strengthen its independent institutions: judicial reform, the creation of anti-corruption bodies, and the launch of Suspilne Movlennia (Public Broadcasting). Also, Ukraine implemented the decentralisation reform.

However, the influence of the oligarchs remained, and corruption scandals broke out. People wanted something new to change the whole system. This time, the protest was not on the Maidan but at the polling stations. In 2019, 73% of Ukrainians voted for Volodymyr Zelenskyy, a film producer, actor and comedian with no political experience. During his inauguration, he dissolved the parliament and won a mono-majority in the Verkhovna Rada in the snap elections.

Yevhen Hlibovytskyi, a member of the Nestor Group and the Supervisory Board of Suspilne Movlennia (Public Broadcasting) member, wrote in his opinion for Svidomi that Ukrainians have developed a unique way to "tame" the state and protect themselves from the totalitarian legacy. After a president is elected, their personal approval rating may remain high, but institutional credibility is taken away.

According to polls by the Razumkov Centre, in 2021, more than 70% of citizens distrusted the government, parliament, prosecutors and the judiciary, and 61% distrusted President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

All this time, Ukraine has had to balance respect for freedom of speech with countering Russian information influence: Russian social media and television programmes have been banned, and in 2021, the National Security and Defence Council imposed sanctions on three TV channels of pro-Russian politician Taras Kozak that promoted Kremlin narratives.

It was the starting point for Ukraine when Russia started the full-scale invasion in February 2022. At that time, Ukraine introduced martial law, and the level of democracy and the democratic system changed significantly.

Democracy and martial law

Martial law, which has been in force in Ukraine since February 24, 2022, allows for restrictions on a range of civil rights and freedoms, including the inviolability of the home, freedom of thought and assembly. Men of the conscription age who are not subject to exemptions cannot travel abroad, and there are curfews in the regions at night when businesses close and people cannot move around the streets. The closer a region is to the frontline, the earlier the curfew starts.

Although there is a ban on mass gatherings and protests, every weekend, in Kyiv, activists demand that funds from the local budget be allocated to the Armed Forces of Ukraine, and in Kharkiv, 30 kilometres from the Russian border, a KharkivPride rally was held in 2023. Police officers kept order and did not interfere with the assembly.

Petro Burkovskyi, an analyst at the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation, writes in his study of Ukrainian democracy during the war about the reorganisation of the state system: the president has received new powers over the Cabinet of Ministers, while the role of parliament has been weakened.

Plenary sessions of the Verkhovna Rada are held every few weeks. Dates and agendas are not announced in advance, and journalists still do not have access to the Rada and the 'government block' ( where the Office of the President, the Verkhovna Rada and the Cabinet of Ministers are located — ed.) in Kyiv to talk to politicians.

During a press conference announcing the results of 2023, Volodymyr Zelenskyy said that his team consists of five or six managers. If they are removed, Ukraine will become weaker, with fewer air defence systems and less aid. The president did not name these managers.

At the local level, decentralisation reform is at risk due to the creation of military administrations, where the heads are not elected representatives but are appointed by the president via decrees. Sometimes, such changes in the territorial structure were politically motivated, and military administrations unreasonably operate in communities far from the front line, such as in Hostomel in the Kyiv region, which was liberated by the Ukrainian military in April 2022.

"The establishment of military administrations was quite justified in the first stages after de-occupation. But now local governments are having problems because of this," Oleksii Koshel, head of the Committee of Voters of Ukraine, told Svidomi.

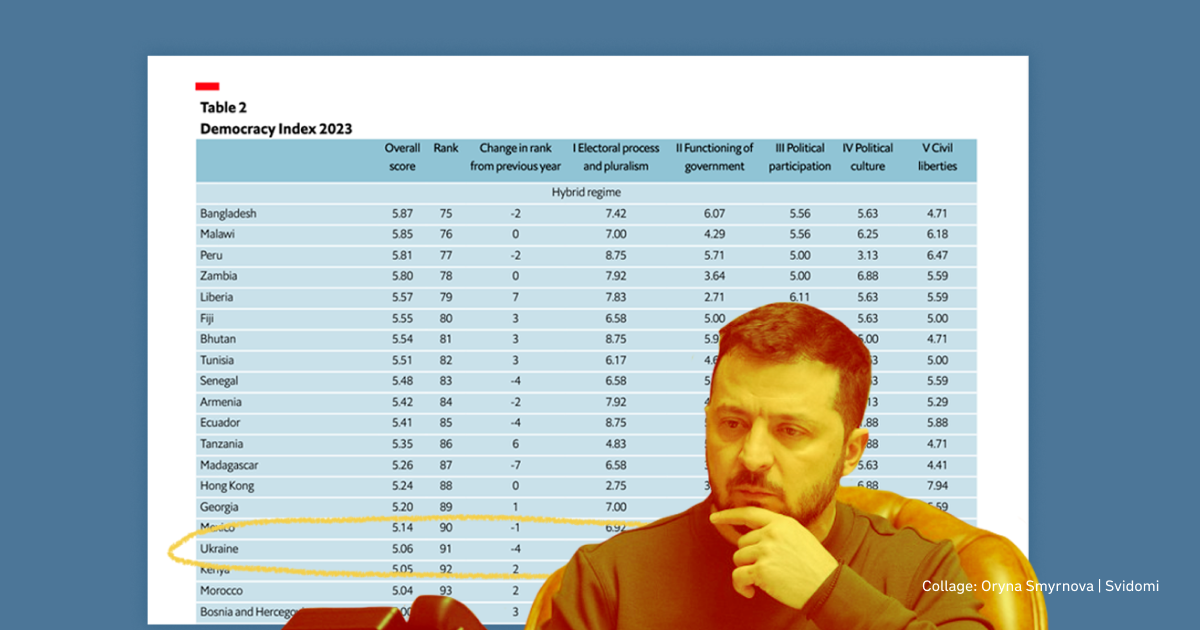

Last year, the Economist Intelligence Unit published its Democracy Index entitled "Frontline Democracy and the Battle for Ukraine". Despite the martial law, Ukraine's score in 2022 has not changed significantly (5.42 compared to 5.57 in 2021).

In a 2023 report, researchers at The Economist Intelligence Unit admit that the war is damaging democratic institutions, with power becoming more concentrated in the hands of Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Corruption remains a problem. Ukraine has dropped four places in the world's democracy rankings — from 87th to 91st.

Despite martial law, no censorship was introduced. Ukrainian information policy was more political: at the beginning of the invasion, opposition channels from the pool of Volodymyr Zelenskyy's predecessor, Petro Poroshenko, were taken off the air, and other channels producing news content were merged into the 24-hour news programme "United News".

The online media still has a plurality of views and criticism of the government. At the end of 2022, a new media law that meets the requirements of the European Commission was passed. In the Reporters Without Borders (RSF) ranking, Ukraine moved from 106th to 79th in terms of freedom of speech in 2022.

"At that time, we managed to find a balance between information protection and freedom of speech. The aggressor country committed the overwhelming majority of crimes against journalists," Yaroslav Yurchyshyn tells Svidomi. In 2022, the Ukrainian Institute of Mass Information recorded 567 violations of freedom of speech, more than 80% of which were committed by Russia: murders, captivity and obstruction of journalists' work.

Yurchyshyn says that Ukraine is unlikely to be able to maintain the positive trend in freedom of speech. He cites the harassment and wiretapping of journalist Yurii Nikolov and Bihus.info. The latter claim that their phones were wiretapped for about a year by the Security Service of Ukraine, whose officers then arranged video surveillance of the investigative journalists.

It is important to show that we are not a small post-Soviet country at war with a large post-Soviet totalitarian country. We are a European state that understands the value of freedom of speech even in times of war,

concludes the head of the Parliamentary Committee on Freedom of Speech.

It is hard to call e-democracy effective. Citizens can register an electronic petition to the president; if it gets 25,000 signatures, the head of state will consider it. A successful example is a petition demanding the opening of a register of property declarations of public officials. It gained more than 83,000 signatures in a few days, and Zelenskyy vetoed the law that would have closed the register to the public. Many more such petitions remain ignored.

Polls are conducted on the state-owned Diia app, but they are related to street renaming or the choice of Ukraine's representative at Eurovision.

Public sentiment

Ordinary people in Ukraine are willing to fight for their right to democracy. Even if they know not everything is going to be ideal, it's better than the other option. We know what the other option is — it’s Belarus and Russia. That shaped how people responded to the invasion in 2014 and to the full-scale invasion in 2022,

says Emily Channell-Justice.

According to polls conducted by the Razumkov Centre, in May 2023, 93% of Ukrainians expressed their support for a democratic type of government. The Kyiv International Institute of Sociology provides a 94% result.

How to preserve democracy

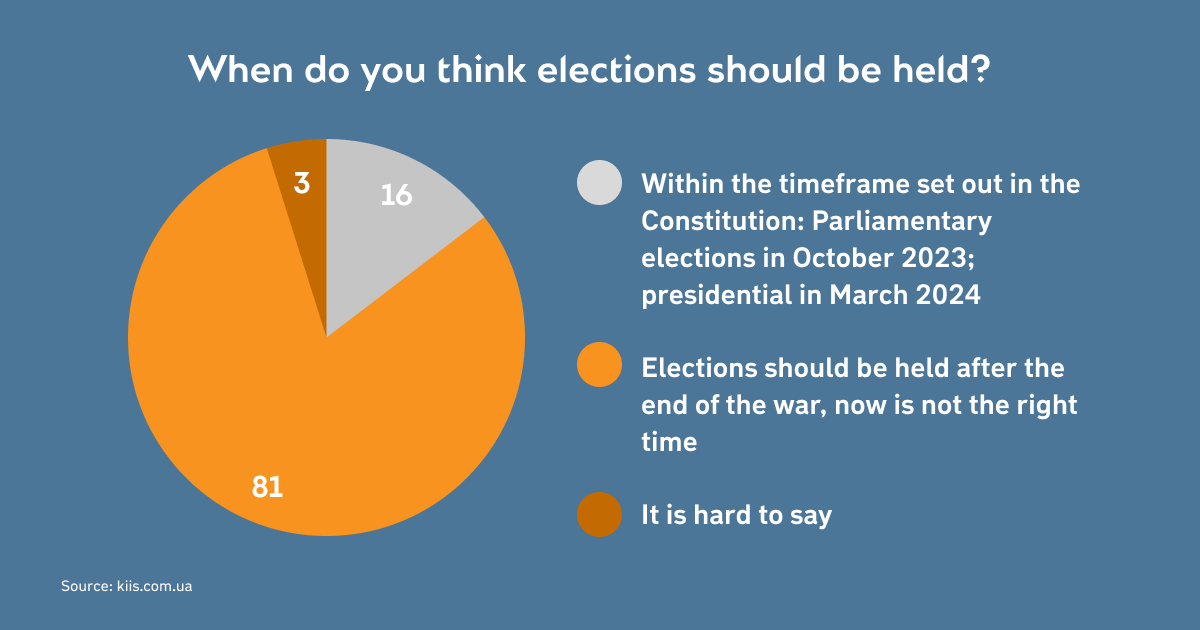

In October 2023, 81% of Ukrainians responded that elections should be held only after the end of the war. Civil society organisations issued a joint declaration against holding elections, arguing that they divide, distract and destabilise society. Volodymyr Zelenskyy has also said it is not the right time to hold elections.

As the war continues, the question of how to ensure the government's legitimacy and avoid its centralisation in the President's Office will become more and more relevant. This risk arises when other democratic institutions are weak.

Researchers at the Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chatham House, write that this weakness is evident because the Ukrainian judiciary has never functioned well or independently and is vulnerable to corruption. Political parties have often been projects to support the interests of individual business people or oligarchs.

"Having strong journalism and legal accountability institutions, a strong judicial system, and non-governmental institutions that can help hold political leaders accountable is the key to the future. It's really important to see that no group, whether it's Zelensky or the Armed Forces, has a total monopoly and total control. Because at that point, the measure of democracy in Ukraine will decrease," says Emily Channell-Justice.