Ukrainians' trust issue: the impact of war and totalitarian trauma

Yevhen Hlibovytskyi

Understanding Ukrainians. How does Ukrainian society form its trust in the president? How are they affected not only by Russia's current aggression but also by the world wars of the past and the Soviet Union? Why are Ukrainians like the world sees them today?

Yevhen Hlibovytskyi, a member of the Nestor Group and the Supervisory Board of Suspilne movlennia (Public Broadcasting) member, explains in his opinion for Svidomi.

This article is published as part of the special project "The War Continues: A History of Ten Years of Resistance"

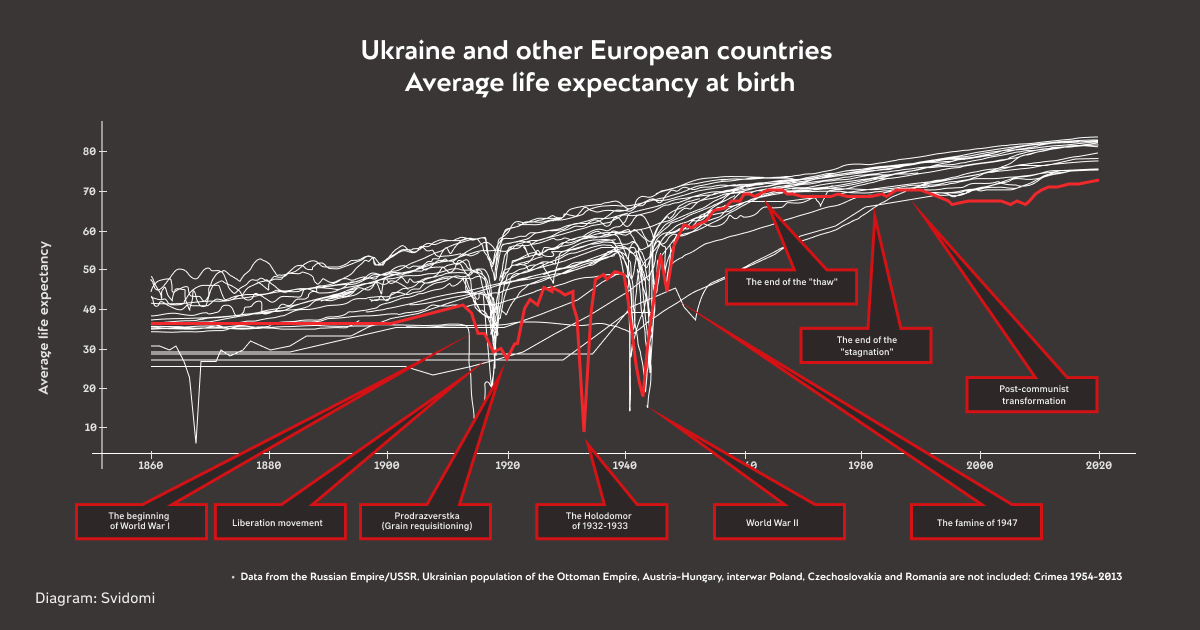

A comparative map of life expectancy between Ukrainians and residents of other countries on the European continent shows that in the mid-nineteenth century, Ukraine had average indicators: some countries fared worse, others better.

As we move to the present day, we see that Ukraine is firmly in the last position on the European continent. The living memory of Ukrainians reflects two major wars (World War I of 1914-1918 and World War II of 1939-1945 – ed.), the loss of independence (the Ukrainian Liberation Movement of 1917-1921 – ed.), the Holodomor (1932-1933), repression, the post-war famine of 1947, and a complex post-communist transformation.

Each time, it was necessary to adapt — not everyone did. Each time, disasters differed, and preparing for the next one from the previous experience was impossible.

Each of them led to a decline in the population: people of young age often died before they had time to leave their descendants. These consequences can be seen in the demographic pyramid.

In 2015, after the start of the Anti-Terrorist Operation in eastern Ukraine, which began as a result of Russia's invasion in 2014, Ukraine experienced a shortage of veterans' rehabilitation specialists. Among those foreigners who came to help was Pete Shmiegel, CEO of Lifeline Australia, the National suicide prevention strategy for Australia’s health system. He is an ethnic Ukrainian and knows Ukraine's history well.

When he arrived here, he was startled at how that previous history of disasters looked regarding social psychology. Shmiegel says that every country has its own traumatised groups. For example, PTSD is an occupational disease of police officers or firefighters. In Ukraine, he saw that trauma was widespread throughout society.

He began to speak out publicly, stating that it was impossible to effectively help veterans reintegrate back into civilian life here because it meant re-traumatisation.

Regular peaceful life in Ukraine is an entire trauma.

I have identified two components of the origin of this trauma: totalitarian and colonial.

Totalitarian trauma is associated with the use of force. In this case, the state is super-powerful, unaccountable, and controls almost every aspect of a person's life. Any manifestation of leadership or subjectivity increases the risk of death.

In such circumstances, corruption becomes a tool of security and survival that citizens cling to. This is what people in the West do not understand.

Totalitarianism is so horrible that a transition to autocracy is perceived as an improvement in conditions.

The Western experience with totalitarianism is short: Nazi Germany — 10-12 years (1933–1945 – ed.), Fascist Italy — about 20 years (1922–1945 – ed.). After the Western world faced totalitarianism, the so-called V-shaped recovery took place: one generation fell out as the generation formed under totalitarianism, and social competencies were passed directly from the elders to the younger ones. It worked when no more than one generation fell out.

In the Soviet Union, the totalitarian period was the Stalinist period (1922–1953 – ed.), followed by autocratic periods that tended to descend into totalitarianism. This trauma remained deep; it could not heal, and at some historical moments, it even worsened.

In Ukraine, there are three generations formed within the totalitarian trauma, and they have no other social experience to go by. All they know is trauma.

Totalitarian trauma makes you constantly alert, focused and mobilised. It leaves behind trails of rigid institutions.

The essence of the colonial trauma lies in the fact that one cannot create their own rules.

From the end of the Hetmanate (the Ukrainian Cossack state that existed from the mid-17th century) in the late 18th century until the declaration of independence in the late 20th century, there was no local government in Ukraine. The only place to put one's managerial talents or Ukrainian approach to work would be within the family.

To make a career in the Soviet Union, you had to go through several glass ceilings. One of them was membership in the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which imposed cultural obligations, among other things. You had to get rid of the "peasant language" (the Russians used to say that Ukrainian was the language of the villagers - ed.) and speak Soviet, that is, Russian. You had to renounce a large part of what shaped your identity.

The mixture of these two traumas determined the trajectory of Ukraine's development: in the 1990s, there were many confused people. It took us almost a generation and a half to get out of that state. Today's Ukrainians are self-aware and can quickly come up with solutions.

The depth of this trauma determines the unique role of empathy. This is one of the reasons why Ukraine is so inclusive, not xenophobic, not anti-Semitic, and ready to welcome [people of other identities].

Over the past 30 years, Ukrainian identity has moved from ethnic to civic categories.

Before, being Ukrainian was determined by the right of blood, i.e., being born Ukrainian. Now, the concept of Ukrainian identity has shifted towards self-determination.

The glue that holds society together is the result of all traumas. That is why empathy will be at the heart of Ukrainian identity until we recover from trauma. And so far, there is no light at the end of the tunnel.

Ukrainians and trust

To understand how trust is formed in today's context, we must take a deeper look at how independent Ukraine was born.

On March 17, 1991, Ukraine held a referendum on preserving the Soviet Union. 70% of Ukrainians said they wanted to stay in the Soviet Union. In their opinion, the late Soviet social contract was comfortable: there was no more totalitarianism, no one took you to Siberia (a remote region of Russia where the Soviet government sent people to prison – ed.), you could say something, but inactivity was rewarded — you gave up your political or civic subjectivity, and for this, you received social promises from the state.

This social contract seemed comfortable until the question of its possible destruction arose. The national liberation movements were weak at the time. Still, there was a coup in Moscow (an attempted coup d'état in 1991, when the self-proclaimed State Committee for the State of Emergency tried to remove Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev from power – ed.) It spoke to Ukrainian society: "We, the Soviet state, are proceeding from a social contract, according to which you are not subjective, and we take care of you. You are no longer subjective, but we now do whatever we want with you." This was the reason the coup failed — the citizens were no longer ready to accept this.

Ukrainians perceived what happened after the coup as a need to escape the threatening state of the USSR. The people gave the authorities the right to make any changes they wanted so that nothing would change. In the referendum of December 1991, 90% supported an independent Ukraine, while 60% elected a communist [Leonid Kravchuk] as President.

Independent Ukraine extended the life of Soviet institutions along with the trauma of Ukrainian citizens concerning those institutions.

No one destroyed more people on the territory of the Soviet Union than the Soviet Union itself.

When we talk about all these circumstances, we recall the protests. But the protest of the Revolution on Granite (the student revolution of 1990 against the signing of a new union treaty and demanding re-elections to the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR – ed.) achieved only the least essential demand: one communist replaced another (the resignation of the head of the Council of Ministers of Ukraine, Vitalii Masol, and the appointment of Vitold Fokin – ed.)

The Orange Revolution of 2004 (the revolution occurred due to fraud in the presidential election, which led to a third round of voting. As a result, Viktor Yushchenko became President of Ukraine, not Viktor Yanukovych, who "won" the second round of elections. Yanukovych became President in 2010 and fled to Russia in 2014 – ed.) succeeded in changing the personality, not the rules.

Only the Revolution of Dignity led to the emergence of a new Ukrainian political entity (the reason for the revolution in 2013-2014 was the refusal of the current government to move towards EU membership. The rally, which lasted from November 2013 to 23 February 2014, led to a change of government, the European vector of foreign policy and reforms in Ukraine. During the confrontation with the police, more than 100 protesters were killed – ed.).

Speaking of the historical countdown through the criterion of subjectivity, Ukraine has been independent since 2014, not 1991.

The immediate response to this was the war with Russia: the occupation of Crimea and the hostilities in the east (Russia launched military aggression against Ukraine and occupied the Crimean peninsula in 2014 when Ukraine was politically unstable after the revolution and the escape of the country's pro-Russian leadership – ed.)

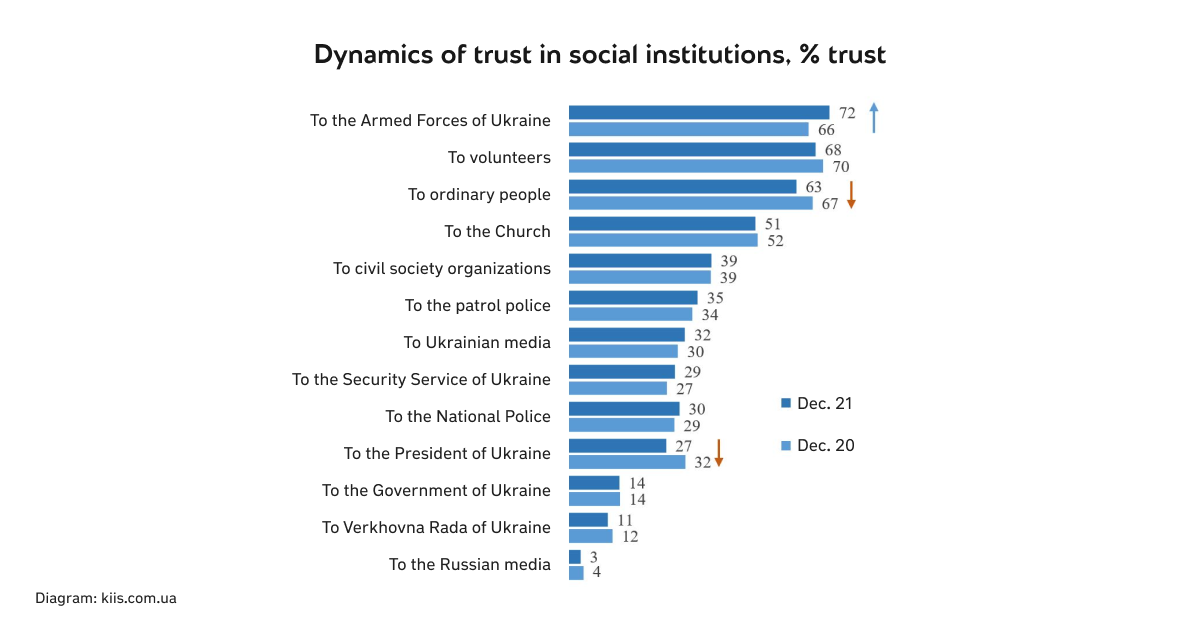

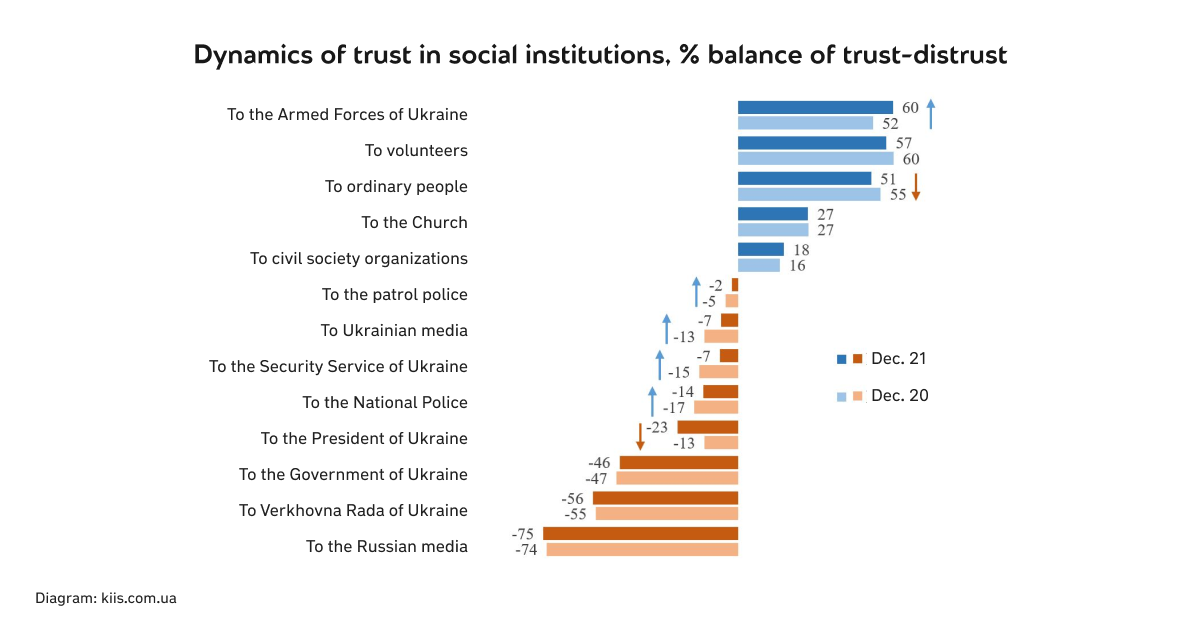

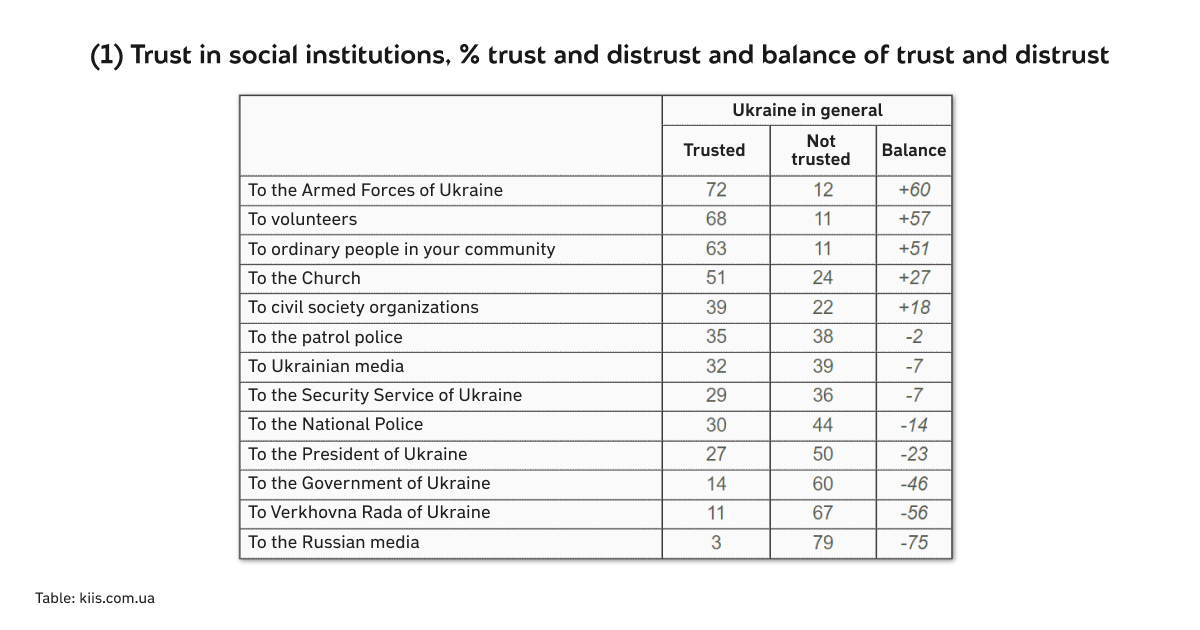

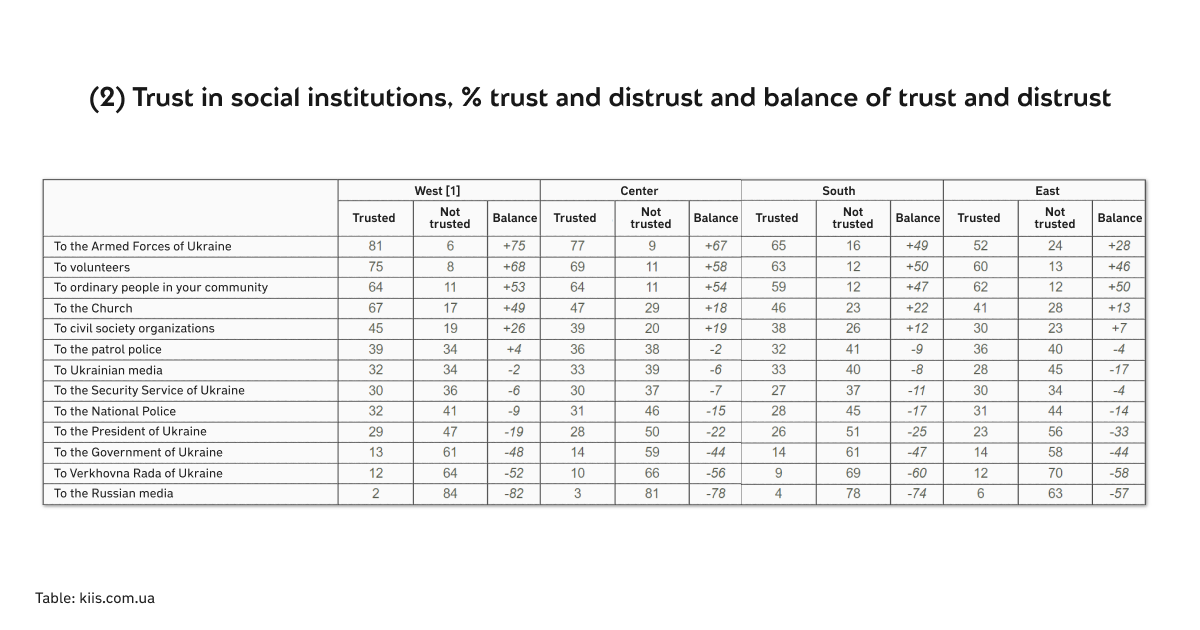

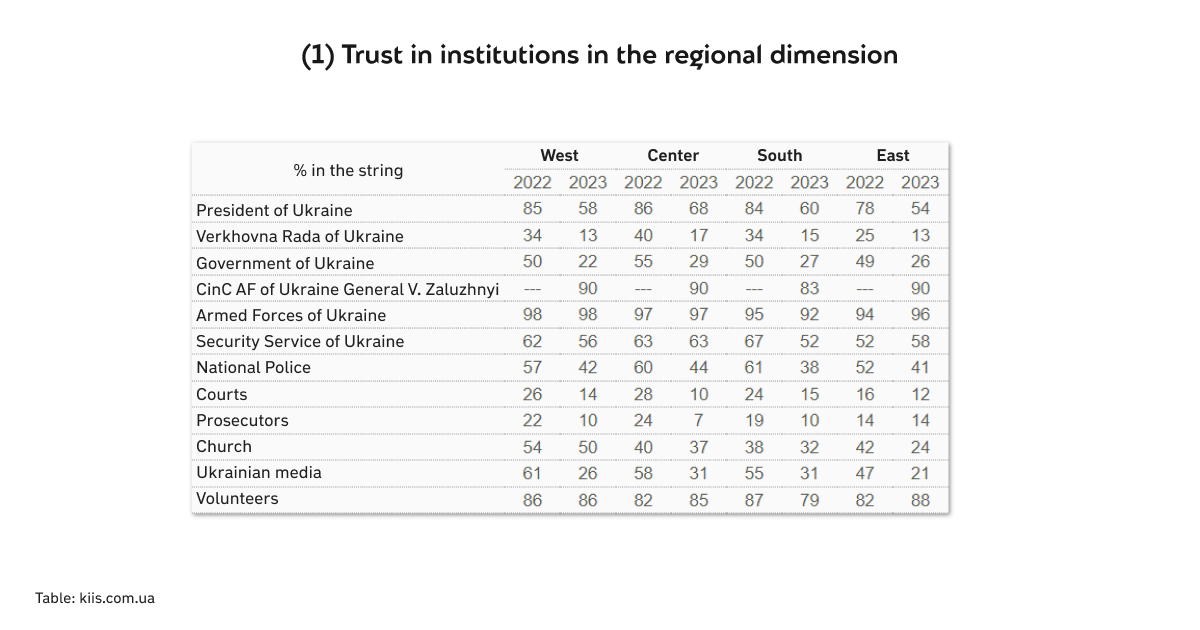

All of this directly affected the way approaches to institutional trust were developed. Before the full-scale invasion began in December 2021, according to a Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) survey, the Armed Forces of Ukraine, volunteers, ordinary people, the church, and NGOs had a positive balance of trust.

Anyone who has a weapon and is not at war with Russia (police, Security Service – ed.) was seen as a potential threat. The president, the government and the Verkhovna Rada were in the red zone. The only things that scored worse were those associated with Russia.

These survey results show that we still consider the state alien post-totalitarian and keep it at a distance. If we need something, we have a set of intermediaries — volunteers, the church, people and NGOs.

The full-scale invasion forced Ukrainians to take off their masks and tell themselves that this state — whether it was founded as a sequel to the Soviet version or on new principles — is still ours.

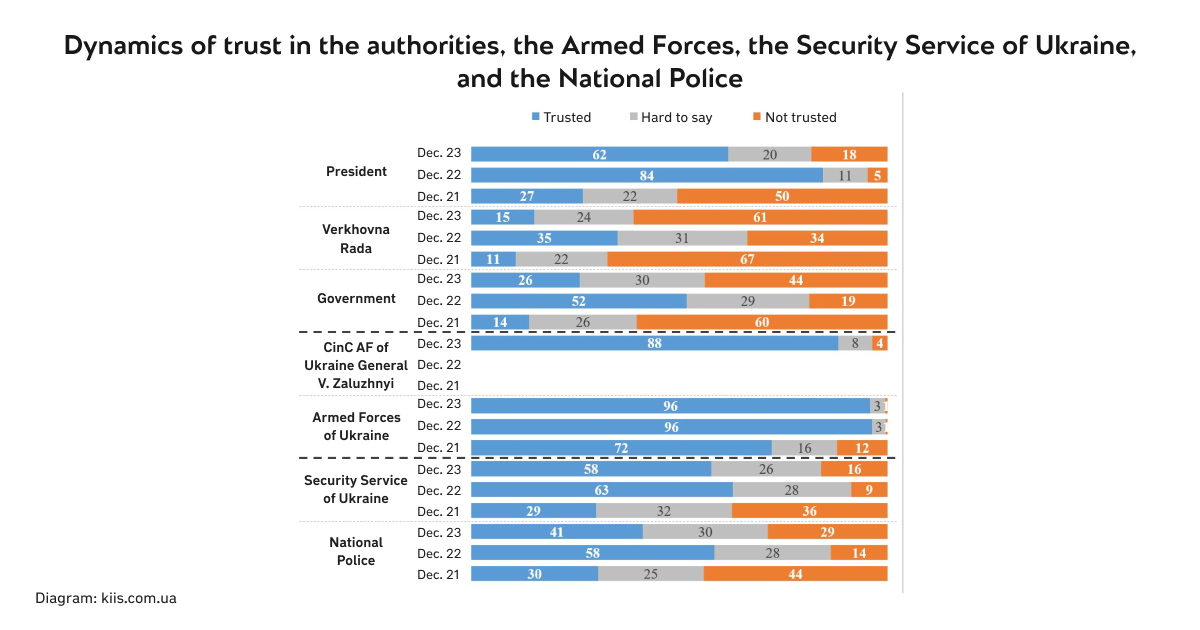

Then, there was a dramatic change in trust: The President of Ukraine, the National Guard, the National Police and volunteer units, the Security Service, the government, and the Verkhovna Rada — all have a positive image.

Society is giving the state an advance in trust. This is a unique way Ukrainians have learned to tame the state. After a president is elected, their rating (as a personality – ed.) may remain high, but Ukrainians take away institutional trust. This is a way of protecting themselves from the totalitarian legacy.

In 2022, the state used this advance of trust to build an international coalition and strengthen Ukraine's Armed Forces. But at the same time, it restricted freedoms and found ways to reduce pluralism.

In response, in 2023, society returned to its previous position — trust in all but those involved in the defence of Ukraine fell again.

Ukrainian society is beginning to take a more critical approach to who is the provider of strategic security and who it still sees as an unreformed threat. And this is the answer to what we want to see in the future.

In the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development –ed.) framework for trust in government, the components of trust are two competencies and three values:

Responsiveness — providing accessible, efficient and citizen-oriented public services that meet people's needs and expectations and transform over time in line with those needs.

In Ukraine, we know that responsiveness in the public sector can only emerge when we influence the human factor. Most of the time, it is caused by corruption.

The state moves in the direction indicated in the OECD definition only when the ground is slipping away from under its feet. That's when digitalisation or other tools come into play to help citizens get what they want without interacting with the state. However, the realism of people's expectations is seen as a problem.

Reliability is the ability of administrations to minimise uncertainty for people in the economic, social and political spheres and to act consistently and predictably in response to uncertainty.

In the area of reliability, all we know about the motivations of the political sector in the so-called "hype democracy" we live in is that it is creating uncertainty, not reducing it. It is an increase in anxiety and threat and a decrease in trust.

Integrity is the conformity of state institutions to broader principles and standards of behaviour to protect the public interest while mitigating the risk of corruption.

The "broader principles and standards of behaviour" have only a Soviet definition - there is an apparatus of coercion but no service. Therefore, until the essence of state institutions is redefined, relations with civil society institutions will not be redefined.

Openness/inclusiveness is the extent to which information is accessible to citizens who can then use it, actions and plans are transparent, and comprehensive ways of interacting with stakeholders are used.

Openness is not about placing an advertisement in the Uriadovyi Kurier (the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine – ed.) newspaper, where no one will read it to say later that no more applications can be submitted.

Fairness — consistency in treating people or organisations when developing or implementing policies.

These are all five items that we lack. And if they fail to appear, trust will remain low.

We will still be in a situation where citizens will play a zero-sum game with the state and those whom they perceive as intermediaries with the state: no security — no win-win.