"Russia is committing cultural genocide": how Russians are destroying the culture and Crimean Tatar (Qırımtatar) language

On the night of February 26-27, 2014, the Russian military seized the Verkhovna Rada and the Council of Ministers of Crimea (Qırım). Since then, the peninsula has been under Russian occupation.

Russians are actively eradicating the culture and language there, destroying the Crimean Tatar (Qırımtatarlar) identity. This was happening even before the invasion in 2014, and it has been happening every day for nine years.

After the conquest of the peninsula by Russia in 1793 and especially after the deportation in 1944, there remained few cultural monuments of the Qırımtatarlar in Qırım. Now the occupation authorities are also trying to destroy these remnants,

said Mustafa Dzhemilev, leader of the Qırımtatarlar.

Read more about how Russians are destroying the cultural monuments of the Qırımtatarlar, but the Qırımtatarlar continue to protect and revive their own identity despite all the challenges in the article

Destruction of monuments

During the temporary occupation of Qırım since 2014, Russia has added more than 150,000 cultural properties of Qırımtatarlar to its state registers, according to Elmira Ablialimova, former director of the Bakhchysarai (Bağçasaray) Historical and Cultural Reserve and expert at the Crimean Institute for Strategic Studies.

About eight thousand objects of the peninsula's immovable heritage have been added to Russia's state registers. In addition, Russians are conducting archaeological research in the temporarily occupied territories. Ukraine does not know about the objects found on the peninsula after the occupation, so it will be even more challenging to prove the theft of excavations.

The Russians have almost destroyed the ancient suburb of Tauric Chersonesos, an ancient Byzantine city-state founded in the fifth century BC and included in the UNESCO World Heritage List.

The Russians have carried out "excavations" there: first, they brought in excavators, and the work is being carried out so that some of the information about Chersonesos' past is lost. It is the destruction of the original appearance of Chersonesos, its identity, and physical evidence of the existence of the ancient city.

Russia transferred the military units located on the Chersonesos suburb's territory to the New History Foundation. This is a fund of the Russian Orthodox Church, headed by Metropolitan Tikhon, the so-called 'Putin's confessor',

Evelina Kravchenko, a senior researcher at the Institute of Archeology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, told Ukrinform.

By destroying the true history of Chersonesos, Russians are imposing the narrative that it is the "cradle of Russian Orthodoxy". In particular, first-graders in the schools of the temporarily occupied Sevastopol (Aqyar) are told that "Russian Prince Vladimir (Volodymyr Sviatoslavych was a Kyivan prince — ed.) baptised Russia in Chersonesos" (Volodymyr spread Christianity in the territory of Kyivan Rus, baptising Rus in 988 on the Pochayna River in Kyiv — ed.)

Russians also "reconstruct" and change the original appearance of monuments. An example is the Khan's Palace in Bakhchisarai (Bağçasaray). After the deportation of the Qırımtatarlar in 1944 and until the collapse of the USSR, it was used as a museum and anti-Tatar propaganda centre.

After the temporary occupation of the peninsula in 2014, Russians destroyed the Golden Cabinet of Krym-Gerai Khan and wholly dismantled the palace's roof and stained glass windows.

"We are witnessing the loss of the only object that has survived (the Khan's Palace is the only surviving example of Qırımtatarlar palace architecture after the 1944 deportation — ed.), which is proof of the existence of Qırımtatarlar in Qırım," says Elmira Ablialimova.

"Russia destroys everything connected with the indigenous people of the peninsula. Every year, the Russians conduct archaeological research in Qırım, and Ukraine cannot control how the Russians use the excavated sites. Russia is committing cultural genocide by taking out historical archives," said Denys Chystikov, Deputy Permanent Representative of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Qırım.

Imprisoned artists

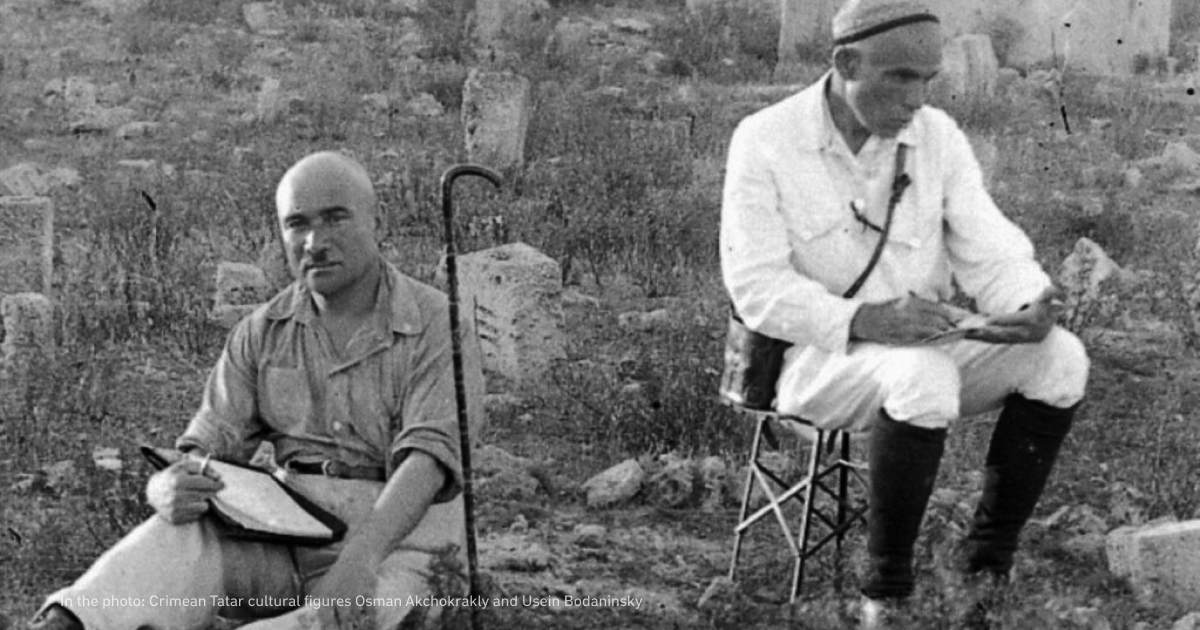

On April 17, 1938, the Soviet authorities shot the most prominent representatives of the Qırımtatarlar — writers, historians, public figures, artists, and teachers.

Üsein Bodaninskiy, an artist, scholar and founder of the Bakhchisarai (Bağçasaray) Palace Museum, was among them. In 1937, he was arrested in Georgia on charges of nationalism and sentenced to death.

Osman Aqçoqraqlı, a researcher of Qırımtatarlar culture, also came under repression. He wanted to study the monuments of Qırımtatarlar antiquity, history and culture of his people. In the summer of 1934, he was fired from the Crimean Pedagogical Institute on charges of nationalism.

In April 1937, Aqçoqraqlı was arrested in Georgia and accused of counter-revolutionary propaganda and espionage. Osman was sentenced to the highest form of punishment in the USSR — execution.

The poet Abdulla Latif-zade actively participated in the campaign to translate the Qırımtatar language from Arabic to Latin script. However, on March 21, 1937, the Soviet authorities fired him as an "ardent nationalist" and arrested him on April 19. He was later executed.

In addition to well-known personalities, the Bolsheviks shot thousands of other lesser-known figures in the Qırımtatarlar movement.

History repeats itself.

On May 16, 2022, Qirim's artist Bohdan Ziza poured blue and yellow paint and allegedly tried to set fire to the doors of the occupation "administration" of Yevpatoria (Kezlev) in protest against the war.

The next day, he was detained. He was charged with four articles — "committed terrorist act", "threat of terrorist act", "call for terrorism" and "vandalism for political reasons". On June 6, 2022, a Russian court sentenced him to 15 years.

On June 10, Ziza began a hunger strike. In this way, the prisoner wanted to achieve the deprivation of his illegally issued Russian citizenship. After 17 days, he stopped the hunger strike: "Weakness is taking its toll, most of all in my arms and legs. I feel dizzy from any movement. I hardly get out of bed," he wrote. Since the end of June, the family has not had any contact with the guy.

It is just one example of the 25,000 Kremlin prisoners illegally detained by Russia.

The language is on the verge of extinction

In 1944, the Soviet authorities organised the deportation of Qırımtatarlar, which had one of the most significant impacts on the development of the Qırımtatar language — people were cut off from their natural environment and forced to use the language of the places of deportation: Uzbekistan, Siberia (Russia) and Kazakhstan.

"The purpose of the deportation and genocide of 1944 was not only the physical humiliation of the Qırımtatarlar but also the destruction of the entire cultural heritage. The names of cities, villages and streets were renamed and Russified. They burned all books in the Qırımtatar language," recalls Mustafa Dzhemilev, the Qırımtatarlar movement leader.

According to Dzhemilev, Qırımtatarlar made great efforts to open schools and establish media, theatre or writers' unions in their native language after returning to the peninsula in 1985-1990.

As of 2022, the number of Qırımtatar language speakers in Ukraine is 20-25% of the Qırımtatar ethnic group, or 70-90 thousand people — more than 350,000 Qırımtatarlar live there.

According to UNESCO's classification, the Qırımtatar language is in danger of extinction. There are two reasons for this: the 1944 deportation and the 2014 Russian occupation.

Since the temporary occupation of Qırım, the language has been taught in schools on the peninsula as an optional subject, as it is not considered necessary. None of the Qırımtatarlar schools that were opened before the occupation are currently functioning.

As far as I know, there are still schools with Qırımtatar as the language of instruction in Qırım, but the number of graduates is a few dozen annually. Children have no place to use the language outside of school except at home,

says Gulnara Muratova, a National Corps of Qırımtatar Language representative.

Revival of the Qırımtatar language and culture

The Qırımtatar should be preserved and restored on the territory of Ukraine, says Mustafa Dzhemilev, leader of the Qırımtatarlar movement.

The most correct solution is the self-determination of the Qırımtatarlar within Ukraine. We are seeking conditions that will allow us to return, revive and preserve Qırımtatar culture within Ukraine,

Dzhemilev said.

On February 23, 2022, the Cabinet of Ministers adopted the Strategy for the Development of the Qırımtatar Language for 2022-2032. One of the main problems is the lack of scientific and educational materials and a consolidated base for its study. Therefore, the Ministry of Reintegration initiated the National Corpus of the Qırımtatar Language project.

The corpus is an electronic database containing Qırımtatar texts of various genres and historical periods. Here, you can find words in context, find out when and in what period they were used, and learn about neologisms.

There are also plans to launch a Qırımtatar publishing house, Kitap Qalesi, in Ukraine. The team is currently working on its first book, a bilingual collection of Qırımtatar folklore in Qırımtatar (Latin) and Ukrainian.

The priorities of Kitap Qalesi are Qırımtatar classics and the development of contemporary authors from the indigenous peoples of Ukraine.

"Our goal is to develop the Qırımtatar language through literature.

To do this, we plan to translate classical Qırımtatar literature into Latin, make translations into Ukrainian, and in the future develop and publish contemporary Qırımtatarlar authors," the publishing house's profile says.

Learning the Qırımtatar language is becoming increasingly popular. This is evidenced by a course in the Qırımtatar language offered by the Ukrainian Catholic University. Enrollment was closed a week after the announcement — even Ukrainians living in the United States, the Netherlands, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, and Lebanon joined.

Despite Russia's attempts to assimilate the Qırımtatarlar, they are resisting, and on the territory controlled by Ukraine, they are trying to preserve the culture and language of the Qırımtatarlar.

For years and centuries, we have been fighting imperial Russia for our memory, land, culture, language, dignity and freedom. Today, we are fighting for the right to live in a democratic society, build our future and develop as a people in our homeland. Even after the fiercest storm, I always say that the sun always appears over our Demirci (a mountain range in the Aluşta region of Qırım — ed.). And it will happen this time,

says Qırımtatarlar journalist and human rights activist Alim Aliev.