Theft of cultural heritage. How to return the treasures looted by Russia?

On June 9, a court in the Netherlands ruled to return the "Scythian gold" of Crimean museums to the territory controlled by Ukraine. It was taken to an exhibition in Amsterdam before the Russian occupation of Crimea in 2014. Ukraine demanded that the collection be returned to Kyiv, while the Russians appealed the decision and demanded that the artefacts be returned to the peninsula. The litigation lasted nine years.

This case is not about the direct theft of heritage but a long struggle for its legal return. However, the Russians took away a lot of Ukrainian cultural heritage by occupying parts of the south and east of Ukraine. What to do if cultural monuments fall into the hands of the occupation authorities?

On June 5, the 20th International Human Rights Documentary Film Festival Docudays UA hosted a discussion within the framework of RIGHTS NOW! & The War Archive — Stolen Treasures: How to Return Ukraine's Cultural Heritage Plundered by Russia?

Read the article about the situation with the Ukrainian cultural heritage, the mechanisms for its return and how to manage them.

Looting before the full-scale invasion

The Russian Empire, the Soviet government, and Nazi Germany stole Ukrainian cultural property throughout the last century. Ukrainian culture went through several decades of the colonial policy of the USSR in the twentieth century, with repression of artistic achievements and their creators.

We have consequences not only of the war that began in 2014. The sacrifices and losses suffered by Ukrainian culture in the twentieth century have not been measured and are not fully understood. We have consequences accumulated for at least the last decades, and in a broader perspective, for the previous centuries,

says Kateryna Chuieva, Deputy Minister of Culture and Information Policy of Ukraine.

In 1929-1930, the Soviet authorities campaigned to sell museum valuables abroad. At that time, several of the most valuable works of European and Asian art were removed from the Khanenko Museum. Thus, Khanenko's unique bronze Aquarius, created in Iran in 1206, ended up in the collections of the State Hermitage Museum [the Museum of Arts in St. Petersburg in Russia - ed.].

During the Second World War, the museum staff evacuated Khanenko's works to Ufa, Russia. The Nazis looted the part that remained in Kyiv during their retreat in 1943. The museum is currently seeking the missing piece of the collection.

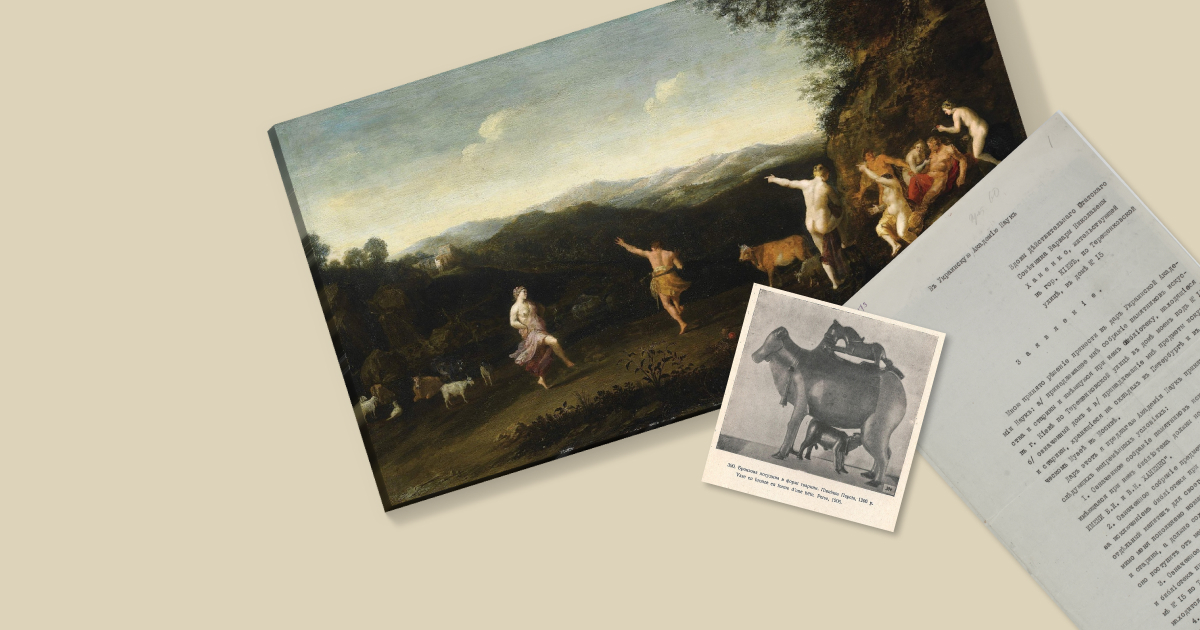

In 2013, a work that belonged to the collection taken by the Germans was found at an auction in Amsterdam. The painting "Arcadian Landscape" by Cornelis van Poelenburgh has already been returned to the Khanenko Museum.

We lost 25 thousand exhibits during the Second World War. Only a few works have been returned. We still have to return the losses of those two wars [World War I and World War II - ed.], let alone this one,

says Olena Zhyvkova, Deputy Director for Research at the Khanenko Museum.

Challenges to heritage preservation

There are several destructive factors in preserving Ukrainian cultural heritage: the war, the specifics of understanding the role of heritage [lack of additional expenditures, payments and government attention to cultural sites - ed.] and restoration. According to Kateryna Chuieva, elements of an integrated programme to restore lost cultural heritage have yet to be developed.

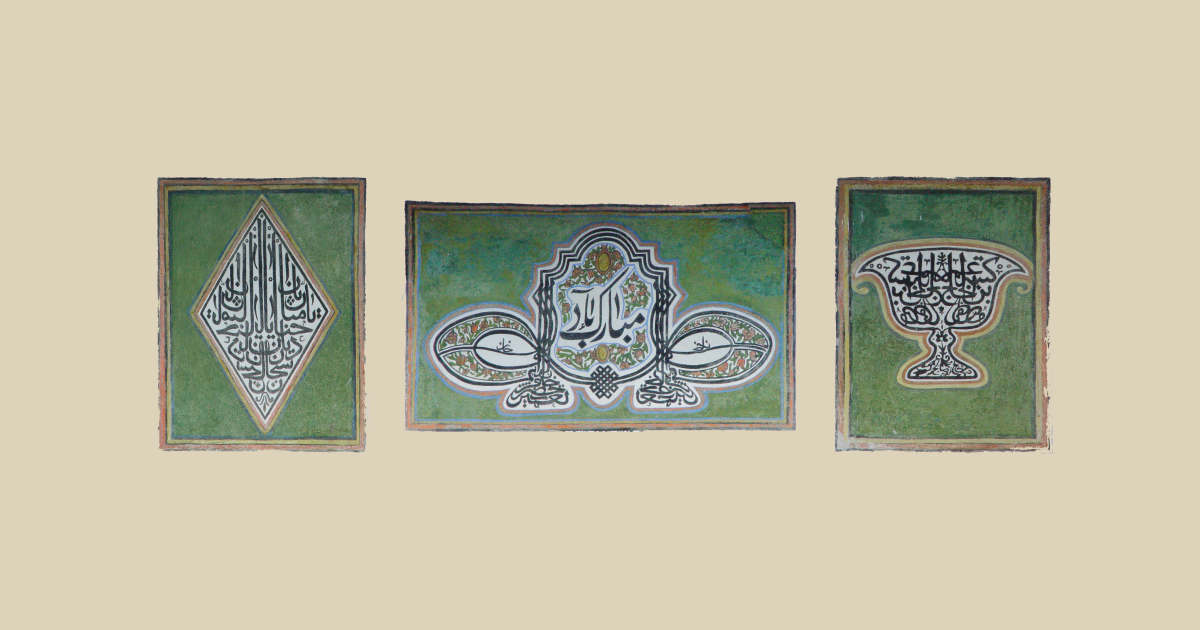

During the temporary occupation of Crimea since 2014, Russia has entered more than 150,000 cultural objects of Crimean Tatars into its state registers, said Elmira Ablialimova, former director of the Bağçasaray Historical and Cultural Reserve and expert at the Crimean Institute for Strategic Studies. About eight thousand objects of the peninsula's immovable heritage have been added to the state registers of the Russian Federation.

Russians are also conducting archaeological research in the temporarily occupied territories. Ukraine does not know about the objects found on the peninsula after the Russian occupation, so it will be even more challenging to prove the theft of excavations.

Another challenge is the deconstruction of cultural heritage and the change of primary identity, which can no longer be restored. An example is Hansaray (Khan's Palace) in Bağçasaray. After the deportation of the Qırımtatarlar in 1944 and until the collapse of the USSR, it was used as a museum and anti-Tatar propaganda centre.

After temporarily occupying half of the island in 2014, Russians are destroying it under the guise of "restoration". They ruined the Golden Cabinet of Krym-Gerai Khan and completely dismantled the palace's roof and stained glass windows.

In 2011-2013, there were agreements to include this monument in UNESCO. The building had already been damaged, so we wanted to support the culture of the Qırımtatarlar. The occupation prevented this from happening. Now there is little left of the historic building, so it is no longer possible to talk about UNESCO membership,

explained Mustafa Dzhemilev, leader of the Qırımtatarlar.

The Hansaray is the only surviving example of Crimean Tatar palace architecture after the deportation of Qırımtatarlar in 1944 and Soviet rule.

"We are witnessing the loss of the only object that has survived [since the deportation - ed.], which is proof of the existence of Qırımtatarlar in Crimea," says Elmira Ablialimova.

Accounting for loot and documentation

To return the cultural heritage stolen during the Second and First World Wars, Ukraine used paper documentation, which included a description of all the exhibits.

Olena Zhyvkova emphasises it is important to keep records of all inventory in museums. According to her, this is the responsibility of cultural institutions. It is also essential to document the participation of the stolen items in exhibitions and shows.

If the museum's activities are archived properly, it makes it possible to compile an evidence base that will testify in court that the item belongs to this collection,

Zhyvkova says.

According to the Khanenko Museum employee, this is the responsibility of each museum, as the state cannot create a database and store all the data quickly due to the large scale and limited resources.

In the temporarily occupied territories, where no records were kept, another mechanism may be searching for and identifying objects through Russian media reporting abductions.

Documentation concerns not only objects from the temporarily occupied territories. Recording monuments all over Ukraine is important because the war also destroys treasures.

There may be different standards and technical capabilities. If it's just a picture taken on a mobile phone, it's better than nothing,

Chuieva says.

The government is currently developing an accounting mechanism.

It's not just about the object, description and data. There will also be things related to urban planning documentation, design, modes of territory use, etc.,

explains the Deputy Minister of Culture and Information Policy of Ukraine.

Repatriation and restitution of cultural property

Ablialimova notes that Ukraine should base its decision on the return of looted culture on national interests.

"Today, at the national level, we need to have a clear, balanced answer to how we treat the issue of restitution. Are we returning the loot or just demanding its return," explains Elmira Ablialimova.

Ukraine should record not only what was stolen but also what was destroyed. It is important to envisage a restitution system and what we can take as compensation for losses.

Our national legislation does not define the term of restitution. We have a term of return, but this term is about voluntary consent. It does not apply to war issues,

says the Crimean Institute for Strategic Studies expert.

An example of the heritage being returned by other countries

In August 1990, the Iraqi army invaded Kuwait. During the military conflict, Iran removed some cultural monuments from occupied Kuwait. Later, the Kuwaiti government wrote statements and prepared lists of cultural property exported by Iraq. Following a meeting and resolution of the UN Security Council, Iraq returned about 25,000 items by October 1991.

In 1991, Iraq also announced the loss of a large number of cultural objects due to the US intervention [interference by one country in the affairs of another - ed.] and civil unrest. The country handed over four volumes with lists of lost cultural property to UNESCO. However, the valuables were not returned due to a lack of evidence: no photographs or descriptions of the stolen items.

At that time, UNESCO once again stressed the need for detailed documentation and photographic records of cultural property so that stolen and displaced items could be returned.

There is also the example of Türkiye when in 1906, the government decided that everything found in Türkiye during archaeological research was state property. Then the government made a statement to all countries asking them to return everything found on the country's territory since 1906.

Ablialimova explains that this is an example of the state's responsible attitude to its cultural heritage, which needs to be defended.

This war is about the existential existence of the Ukrainian nation. Culture is among the factors that create Ukrainians. It should become our national security factor, and its heritage will be protected. Museums today are places about our identity, what we are fighting for and defending,

says Elmira Ablialimova.