Ukrainian is not Russian: the difference between languages and the suppression of Ukrainian

There is a theory that languages are related if one is understandable to a native speaker of the other. However, Ukrainian and Russian differ in many aspects, including lexical and phonetic.

In August 2023, 9% of Ukrainians spoke Russian on a daily basis, compared with 23% in 2022. A number of factors have contributed to the spread of Russian in Ukrainian society. During the Russian Empire and the USSR, and after 1991 with the restoration of Ukraine's independence (Ukraine had been independent since 1918 with the establishment of the Ukrainian People's Republic), Russian was widely used in the media, cinema, literature and music. Instead, Russians can only understand Ukrainian words that are similar to Russian.

This article describes the history of the two languages, their differences and the spread of Russian after the restoration of Ukrainian independence.

History of Ukrainian and Russian

Both languages belong to the Slavic group of the Indo-European language family. Russian is the official language of Russia, Belarus, Qazaqstan and Kyrgyzstan, while Ukrainian is only the official language of Ukraine.

All Slavic languages are descended from the original Proto-Slavic language, which existed until about the sixth century AD, Professor Ivan Matviias, PhD in Philology, wrote. He says that in the 6th-7th centuries, the Proto-Slavic linguistic unity disintegrated, and the East Slavic language split off from it.

The main reason for the emergence of Ukrainian, Russian and Belarusian was the historical conditions that prevailed in the 11th-14th centuries and later in the East Slavic countries. Without these conditions, the territorial Old Slavic dialects would not have developed into separate languages. The three modern East Slavic languages only partially coincide with the Old Slavic dialects in terms of territory,

Matviias explains.

According to historian Oleksandr Palii, the Ukrainian language evolved from local Old Slavic dialects. Ukrainian has retained closer ties with other living Slavic languages.

"That is why average Ukrainians understand Poles, Bulgarians and Croats. However, average Russians from Russia often do not even understand Ukrainian. Therefore, it should be emphasised that neither Russian is a dialect of Ukrainian, nor vice versa," Palii explains.

Paul Jorgensen, a Canadian-born linguist who lives in Japan and runs the YouTube channel Langfocus, says that the misconception that Russian and Ukrainian are almost identical could be due to the widespread use of Russian in Ukraine. Ukrainian is similar to Polish, Belarusian, Bulgarian, Croatian and Slovak.

Lexical and phonetic differences between the languages

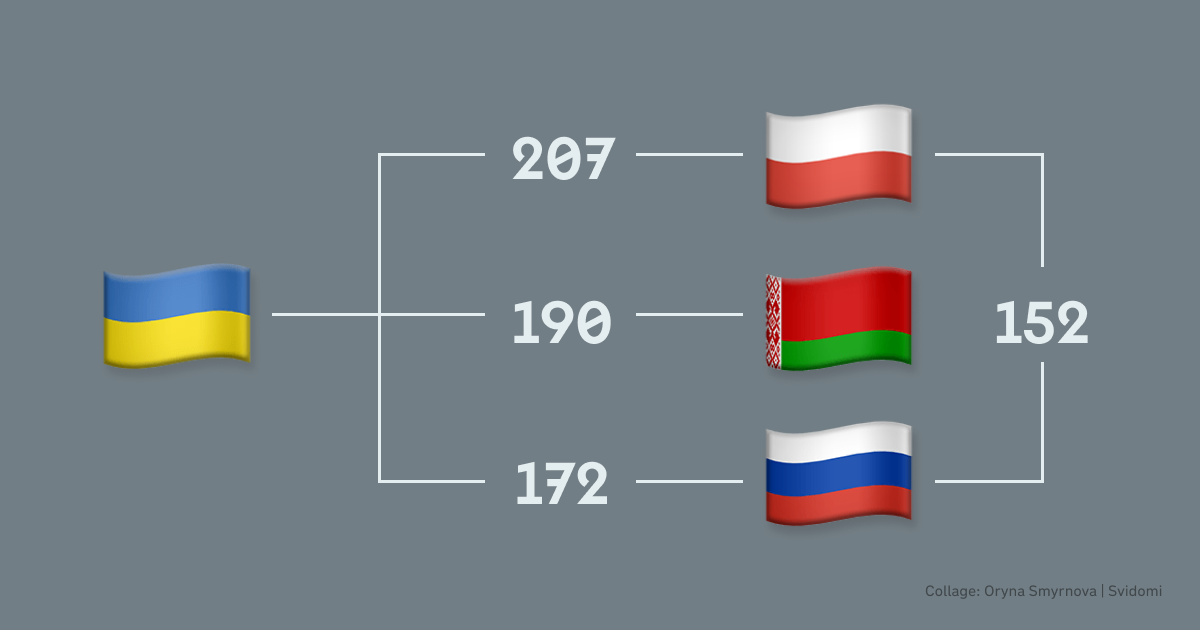

According to a Swadesh list of Slavic languages, Ukrainian matches Russian in only 172 of 207 lexemes. There are 190 out of 207 matches between Ukrainian and Belarusian and 169 out of 207 between Ukrainian and Polish. In particular, Polish and Russian share 152 lexemes.

Both languages use the Cyrillic alphabet. However, some letters are different. Russian has the letters "Ё" ([yo] in ‘yolk’) and "Ы" ([i] in ‘ill’), while Ukrainian uses the letters "ЙО" ([yo]), "ЬО" (soft sign, serves as an indicator of palatalization of the preceding consonant and the vowel ‘O’) or the letters "E" ([e] in ‘met’) and "I" ([i:] in ‘see’).

Such Ukrainian letters as "I" ([i:] in ‘see’), "Ї" ([ji:] in ‘yeast’), and "Ґ" ([g] in ‘girl’) do not exist in Russian. The Ukrainian letter "I" corresponds to the Russian letter "И", and "Ґ"(g) corresponds to "Г" ([g] in ‘goose’). The Ukrainian letter "Г" is pronounced like the Latin "H" ([h] in 'Harvard'). For example, the word "mountain" is pronounced "ho-ra" in Ukrainian.

Russian uses a hard sign (the Russian letter ъ). In contrast, Ukrainian uses an apostrophe (it separates a hard consonant from an iotated vowel so that sounds don’t influence each other). Unlike Russian, Ukrainian has a vocative case (a grammatical category of nominal parts of speech expressing the syntactic relationships between words in a sentence). There are seven cases in the Ukrainian language which help us communicate and determine the correct form of a word.

By their very nature, phonetic features are the least affected by external factors and best preserve the distinctive character of the language.

"These specific Ukrainian features can be found even in the oldest written texts, several hundred years old. This means, among other things, that the Ukrainian language is not only distinctive but also has a long and rich written history," says Uliana Dobosevych, a historian of the Ukrainian language and associate professor of the Ukrainian language at the Ivan Franko National University.

According to the historian, the lexical composition can be traced back to moments that reveal the original face of the Ukrainian language.

"A classic example is a pair of equivalents of the word “to win” in Ukrainian and Russian: перемогти (Ukrainian, is easily read as a modal — subjective, linked to human will — to be able to) and победить (Russian, faceless, inhuman, passive — after the trouble is over)," says Uliana Dobosevych.

says Uliana Dobosevych.

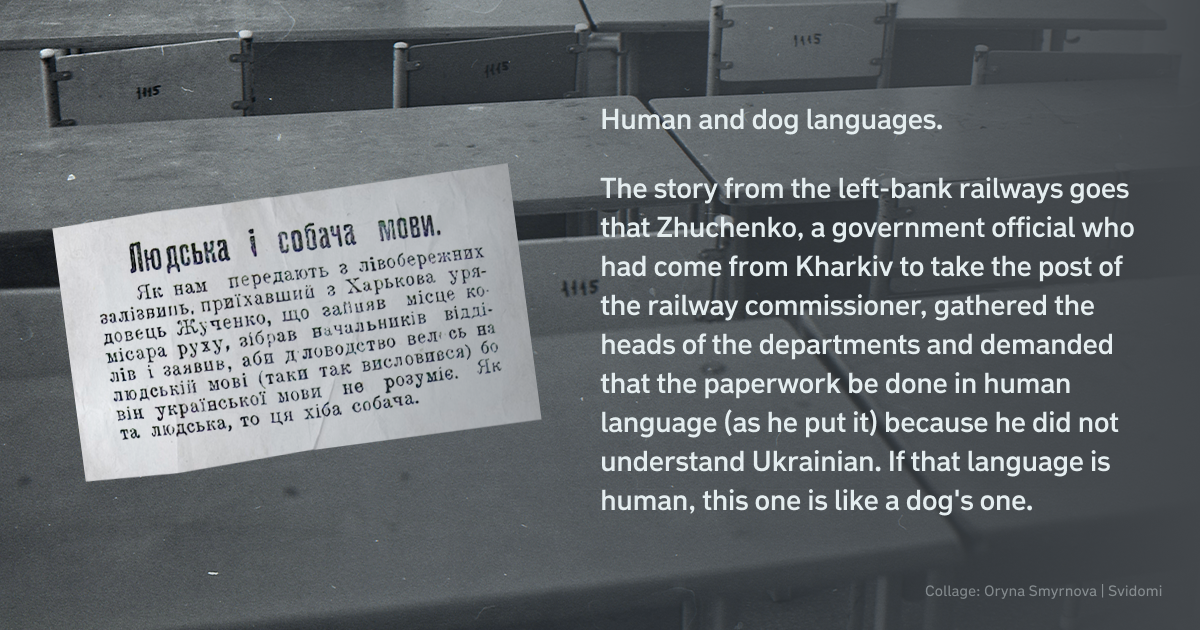

Linguistic violence by the Russians against the Ukrainian language

During the Russian Empire (1721-1917), Ukrainian was banned and considered "Little Russian identity", while Russian was the official language. Peter I, Emperor of Russia, is regarded as the main anti-hero of the formation of the Ukrainian language during the Russian Empire. He was the first to call Ukrainian a "dialect of the Russian language" and tried to eliminate it as a language of instruction in educational institutions.

The struggle against the Ukrainian language culminated in 1720 when Peter I issued a decree banning the printing of new books in Ukrainian. Books already printed had to be published by Russian standards, excluding Ukrainian identity in literature.

Empress Catherine II continued Peter the Great's policy. The Ukrainian language was eradicated from church records during her reign (1762-1796). The language issue became one of the main issues until the end of the 18th century when the autonomy of the Hetmanate and the Zaporizhzhian Sich was destroyed, and the Ukrainian lands were incorporated into the administrative structure of the Russian Empire.

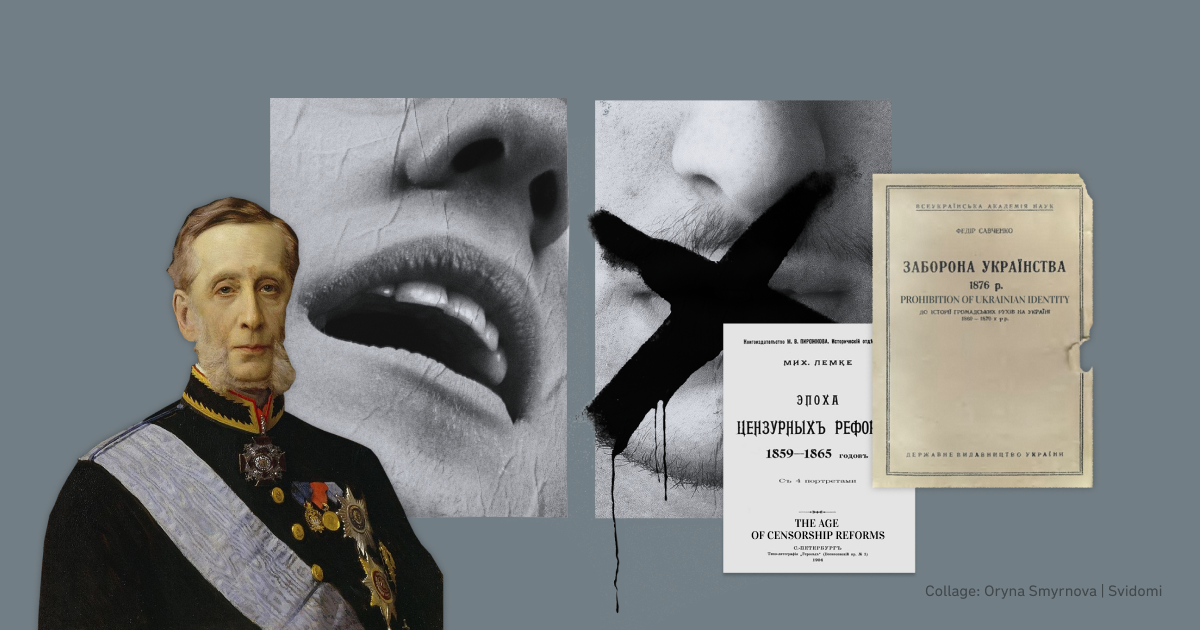

To consolidate this narrative, Emperor Alexander II issued the Valuev Circular (1863) and the Ems Decree (1876), which banned and punished the use of the Ukrainian language everywhere: in the theatre, literature and public spaces.

In return, the Russian authorities killed Ukrainian artists and scholars who fought for the manifestations of the Ukrainian language in culture. Between 1876 and 1880, for example, the scholars and teachers Mykhailo Drahomanov and Pavlo Zhytetskyi were dismissed from their jobs because of their scientific work on Ukrainian studies. Mykhailo Drahomanov and Pavlo Chubynskyi were also expelled from the country.

However, the repression of the language did not end with the introduction of censorship and a ban on the use of Ukrainian. In the 1930s, the Soviet authorities began interfering with the language's internal structure, destroying it from within. In particular, the vocative case was abolished. As a result, it was not used much for a long time.

These changes were made on a massive scale to bring the Ukrainian language closer to Russian, to turn it into a so-called "dialect of Russian". In this way, the language was stripped of its distinctiveness.

In the USSR, Russian became a privileged language. It was the language of education, especially after the decision of the USSR's Council of Ministers in 1978, according to which Russian was to be taught in "the first grades of secondary schools with Ukrainian as the language of instruction" in rural schools, in technical schools, and so on.

Russia's influence on the Ukrainian language after the restoration of independence and during the full-scale invasion

The Law "On Languages in the Ukrainian SSR" came into force in 1989 and was valid in Ukraine until 2012. Ukraine was supposed to ensure "the free use of Russian as a language of interethnic communication", and civil servants "should be proficient in Ukrainian and Russian".

For 32 years, however, the Russian Federation has de facto encouraged Ukrainians' dependence on Russians, especially for Russian-language content. Ukrainians continued to watch Russian programmes on television and Russian films in cinemas.

In 2010, the then Minister of Education and Science of Ukraine Dmytro Tabachnyk (in 2023, he 'ran' for 'People's Deputy' in the temporarily occupied part of Zaporizhzhia, south of Ukraine — ed.) advocated the introduction of Russian language teaching in secondary schools and the restoration of Russian language and literature classes.

As of 2013, Russian culture is being disseminated in school textbooks and radio stations. The share of Ukrainian songs on the radio was 5%. Russian songs accounted for over 40%, with the rest in English and other languages.

Only on November 8, 2016, the law on quotas for Ukrainian songs and language on the radio came into force. At that time, the share of Ukrainian songs on air was at least 35%, and the quota for the Ukrainian language on air was at least 60%.

The use of the Russian language in Ukraine has been declining since the start of the full-scale invasion (in 2022 —ed.). Aware of their loss of influence in Ukrainian society on the language issue, the Russians are only spreading falsehoods about the return of the Russian language to Ukraine at the legislative level.

However, between 2022 and 2023, 14% of Ukrainians abandoned the Russian language. From August 2023, 91% of Ukrainians will speak Ukrainian daily.