Ukrainian Cossacks in the south and how they fit into Ukrainian history

The Ukrainian Cossacks hold a significant place in Ukrainian history, culture, and literature.

As a phenomenon, the Cossacks are inextricably linked to the south of Ukraine since there were several Cossack communities, or Sichs, where they lived in winter camps.

Svidomi talks about the Ukrainian Cossacks in the south and their place in Ukrainian history today.

Defining the Cossacks

Serhii Plokhii, Mykhailo S. Hrushevskyi Professor of Ukrainian History at Harvard University, explains that the term ‘Cossack’ derives from the Turkic ‘qazaq,’ meaning 'warrior', 'guard', and 'robber', etc.

The Cossack is a phenomenon of the steppe, the steppe frontier. Usually, Cossacks lived in no man's land. They lived on islands, in the steppe, but they were not nomads.

The Cossacks, including the Cossack hetmans, replaced the remnants of the Kniaz (ruler, military leader, lawgiver, and tax collector in Rus—ed.) or princely class in Ukraine's history.

At the same time, the Cossacks are not a unique, purely Ukrainian phenomenon—they are Eurasian. They were the creation of a stratum of the population moving into the steppe from the Danube to the Amur. But only those in Ukraine were strong enough to form their own state.

‘But the Ukrainian Cossacks are different from the Don, Amur, Ural or any other Cossacks because they create their own institutions, their own state. For me, the Cossacks primarily mean the creation of an elite and a culture rooted in the experience of the Ukrainian frontier,’ said Serhii Plokhii in a conversation with philosopher Volodymyr Yermolenko.

The place of the Cossacks in the history of Ukraine

Serhii Plohii believes that the Cossacks are a complex historical phenomenon on their own and also complex when viewed from the perspective of development. He distinguishes between the first Cossack uprisings and the creation of the Cossack state and Cossack elite in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

For the first time since Kyivan Rus, the Cossacks brought about the existence and formation of state and local institutions and created their own state elite. According to Plokhii, the Cossack myth has become an important part of the Ukrainian political project, as it is at the centre of the ideas of modern independence. The Cossacks and the Сossack Hetmanate (Hetman state, a historical Ukrainian Cossack state that existed between 1649 and 1764 — ed.) also produced Ukrainian literature, history, and elite.

The historian is convinced that Ukraine would have a different name today without the Cossacks as a phenomenon.

‘When I refer to the medieval use of the term ‘Ukraine’, it was a designation of a territory that was not connected to social or state structures. Ukraine [as a state structure] emerged in the second half of the seventeenth century after the uprising of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi (the Cossack hetman who led the 1648 uprising against the Polish magnates in the southeastern territory of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth that is now Ukraine — ed.). The word came to mean the Cossack state or Hetmanate,’ Plokhii said.

Did Sichs settle in the south?

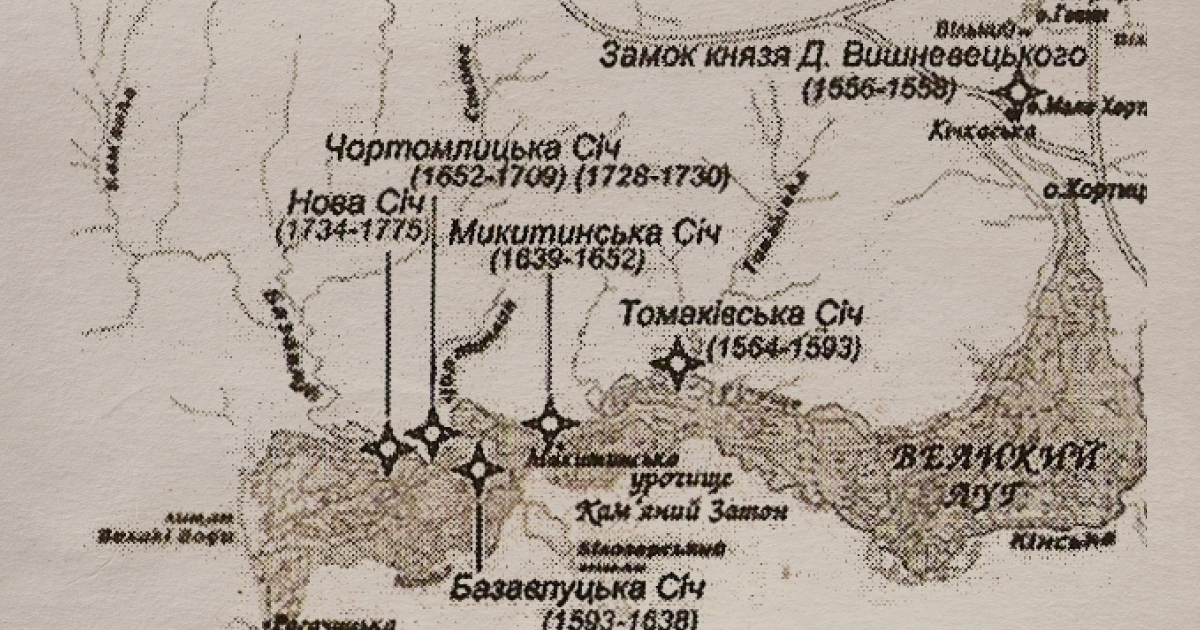

The Ukrainian south became an important component in the formation of the Cossacks as a phenomenon. The island of Khortytsia, located near Zaporizhzhia, is considered the so-called Cossack cradle. Dmytro Baida-Vyshnevetskyi, a magnate and one of the first leaders of the Cossack army, founded the first Zaporizhzhia Sich in 1553 on the island of Baida, formerly known as Mala Khortytsia. On the island of Khortytsia, the Cossacks set up winter camps and engaged in hunting, cattle breeding, beekeeping, farming, and fishing. Later, it was the base of the registered Cossacks.

In fact, Sich was a defensive fortress enclosed by a rampart. In its centre was a square, or maidan, a meeting place for Cossack councils. Around the maidan were Sich huts where Cossacks lived, a cannonry, houses of Cossack chieftains, the office for correspondence and intelligence data recording, etc. Over time, it turned into a huge socio-political centre that made history and shaped worldviews.

The very mention of the Sichs evoked Ukrainian patriotism in people, historian Serhii Bilivchenko said in a commentary to RFE/RL's Ukraine.

The Ukrainian south became the location for several Cossack Sichs: Tomakivka Sich (existed from 1564 to 1593), Bazavluk Sich (1593 to 1630), Mykytyn Sich (1628 to 1652), Chortomlyn Sich (1652 to 1709), Kamianka Sich (1709 to 1711), and Nova Sich or Pidpilnenska Sich (Underground / Сlandestine Sich — ed.) (1734 to 1775).

Many historical events are closely linked to the Sichs located in the south. Bohdan Khmelnytskyi's liberation campaign began with the Mykytyn Sich, which resulted in the creation of the Cossack state. The Chortomlyn Sich was destroyed by the Russians in revenge for the Cossacks, who, together with Cossack Otaman (Chieftain — ed.) Kost Hordiienko supported the protests of Hetman Ivan Mazepa (leader of Cossack-controlled Ukraine, who turned against the Russians and joined the Swedes during the Second Northern War (1700–21 —ed.), and his alliance with King Charles XII of Sweden. Nova Sich was destroyed by the order of Empress Catherine II ( the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796 — ed.).

These Sichs are related to the story of Velykyi Luh (Grand Meadow—ed.), which Svidomi discussed in the article ‘Development of the Ukrainian South: What goals did the Russians pursue, and why was the Grand Meadow destroyed?’

How people see Cossacks today

Oleksandr Muzychko, a historian and lecturer at the Odesa I. I. Mechnykov National University, explains in a commentary for Svidomi that the Cossack phenomenon is an archetype of the Ukrainian mentality, despite current debates among historians and attempts to dismantle it, including through service to the Russians.

In the history of the Scandinavian peoples, the Cossacks can be compared to the Vikings. The Vikings may have had their share of piracy, but can they be erased from Scandinavian history?

Serhii Plokhii believes that the Cossack myth is important, but today Ukrainians need to demythologise it.

'It is important for us to look more closely at the past and to establish contacts and lines of communication with this past, accepting some things and rejecting others. But on the other hand, we need to move away from myth and towards critical thinking,'

says Serhii Plokhii.