Development of the Ukrainian South: what goals did the Russians pursue, and why was the Grand Meadow destroyed?

Russian propaganda claims that these territories were a wasteland before the arrival of the Empire, but this is false. Until the Middle Ages, the Cumans lived here and the Crimean Tatars in Crimea (Qırım). The inhabitants of the region were engaged in agriculture and animal husbandry. Another feature of the area is its access to two seas, which opened up routes for shipping.

Svidomi tells about the South before the arrival of the Russian and Soviet governments and the critical moments in the development of the Ukrainian South.

What was the South like before Russian and Soviet rule?

Serhii Bilivnenko, a historian and lecturer at Zaporizhzhia National University, tells Svidomi that the Ukrainian South is quite a large area, encompassing several regions — the Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, Mykolaiv and Odesa regions. The South stretches from modern Mariupol to modern Budzhak in the Danube region.

It is widely believed that the South was a 'wasteland' before the arrival of the Russian Empire. This, however, is not true. As Serhii Bilivnenko explains, the Crimean Khanate existed in the south of Ukraine before the arrival of the Russians in the 18th century. There were cities like Ochakiv, Izmail, Khadzhybei (today's Odesa), etc. These cities were both multinational and multi-ethnic, with Armenians, Jews and Greeks living there, among others.

Another part of what is now southern Ukraine, below modern Zaporizhzhia on the right bank of the Dnipro, was inhabited by the Zaporozhian Cossacks. The Cossacks lived in winter quarters and farmed when there was no war.

"This concept of the wild field emerged from the European habit of referring to the areas inhabited by nomadic peoples as a wild field. But the South was permanently inhabited. Even before the Middle Ages, the Cumans lived in this region," says the historian.

Later, the Russian Empire defeated the Ottoman Empire in the 1768-1774 war, after which southern Ukraine and Crimea were ceded to the Russian Empire. As a result, the governorates of Taurida, Novorossiya and Ekaterinoslav were formed on this territory.

"When the Russian Empire conquered Crimea, the Greek Orthodox population was forcibly deported to the territory of present-day Mariupol. This explains why the largest Greek community in Ukraine lived there,"

says Bilivnenko.

After the South came under Russian rule, large cities such as Katerynoslav (now Dnipro), Oleksandrivsk (Zaporizhzhia), Kherson and Mykolaiv were built. Ports were built at modern Berdiansk and Mariupol. It was an agricultural region where wheat was grown, and the development of ports made it possible to export grain abroad.

"Mechanical engineering began to develop in the region, and a railway to the sea was built to transport more grain to European countries. It was thanks to foreign capital. Before the outbreak of World War I, southern Ukraine was as much a centre of engineering in the Russian Empire as Moscow or St Petersburg. It was also home to the largest percentage of wealthy peasants," says historian Bilivnenko.

Reconstruction in the USSR: what were the Communists' goals?

The idea of building a dam on the Dnipro originated in the Russian Empire, as the river was considered a promising transport artery for the supply of goods. At the beginning of the 20th century, the first plan was to build a dam with hydroelectric power plants on the site of the Dnipro HPP, but the project was postponed due to World War I.

In the 1920s, the Soviet government set out to industrialise the country. But industry needed energy, so the Bolsheviks began implementing the so-called GOELRO plan (Soviet Russia's plans for national economic recovery and development — ed.), which aimed to electrify the country. Serhii Bilivnenko explains that the Soviet authorities needed to link the mines of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions with the mines of Kryvyi Rih and build a developed industry that required electricity.

"In the Soviet Union, they saw Western Europe and the United States falling apart. For the Soviet Union to succeed, it had to be electrified. The Bolsheviks understood that agriculture could not compete with industry. That is why they decided to build the Dnipro hydroelectric power station and metallurgical complexes, which required large amounts of electricity," the historian explains.

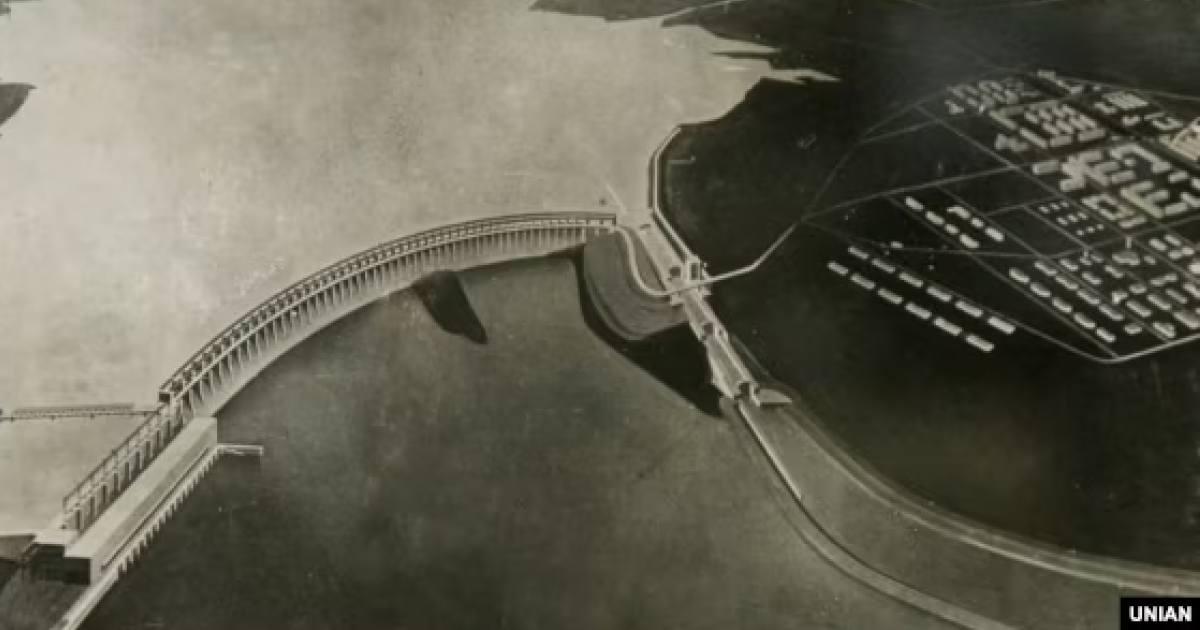

According to Bilivchenko, foreign engineers from the American hydroelectric construction company H.L. Cooper & Co. were involved in the construction. Soviet hydraulic and power engineer Ivan Aleksandrov developed the design of the Dnipro HPP. Construction of the Dnipro HPP began in 1927, and the first hydraulic unit was commissioned in March 1932. Thousands of people, including prisoners, took part in the construction.

According to Ukrenergo (electricity transmission system operator in Ukraine - ed.), the company that now owns Dnipro HPP, the project involved the construction of a dam across two islands in the Dnipro riverbed. This allowed construction to be carried out in stages without blocking the river or creating a bypass channel to divert water during construction. Construction was carried out simultaneously from the left and right banks to the islands.

In parallel with the construction of the Dnipro HPP, Dniprospetsstal, Zaporizhzhia Ferroalloy Plant, Dniprokombinat, etc., were being built to produce various alloys.

"The main goal of the Bolsheviks was industry. They also needed metal, which the Kharkiv Tractor Plant supplied. Another thing is that a big city (Zaporizhzhia — ed.) needs a lot of water. For this purpose, reservoirs are needed. A reservoir is also needed for cooling in production," says Serhii Bilivchenko.

The explosion of the Dnipro hydroelectric power station during the World War II: Consequences

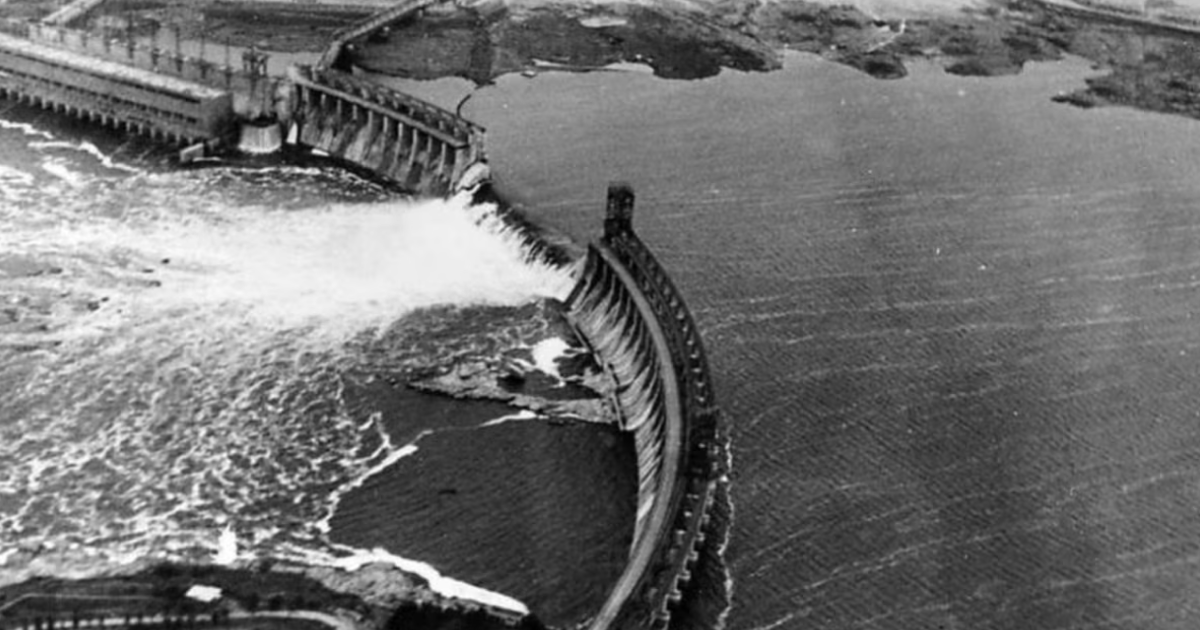

In August 1941, during World War II, as the front line approached Zaporizhzhia, Soviet troops decided to blow up the Dnipro hydroelectric dam to stop the advance of German forces.

Zaporizhzhia historian Volodymyr Linikov told RFE/RL that the retreat of Soviet troops began around noon on August 18.

"The retreat of the Red Army, which in some areas turned into a panic flight. Clearly, there was no way of stopping the Germans on the right bank. So it was decided to hastily blow up the Dnipro hydroelectric power station and the bridges over the Dnipro, which then, as now, passed through the island of Khortytsia. There were two bridges. One didn't work, but the other was blown up. They blew up the dam to prevent the Germans from crossing. Because a dam is also a bridge,"

he said, RFE/RL reported.

The dam was not completely demolished, but only a section of about 175 metres out of a total length of more than 600 metres. Bilivchenko said the dam was blown in the evening. Then, a massive wave of water moved towards the Grand Meadow, where both Soviet soldiers and civilians who had evacuated the city were at the time.

"People from the right bank fled with their children. During the night, they ended up at a point where the water level gradually rose. People died in those conditions. Historians estimate the number at five or six thousand, and then some. Sometimes, they say it was 100,000. That is not true," Bilivchenko said.

In a comment to RFE/RL, Volodymyr Linikov suggested that the number of people killed in the bombing could be as high as three thousand. The Berliner Allgemeine Zeitung reported the same figure. It is impossible to determine the exact number of people who died as a result of the bombing of the Dnipro hydroelectric power station, as the dead were not counted.

The German occupation administration tried to repair the dam and patch its holes. During the German occupation, the plant produced some industrial electricity.

The second explosion of the Dnipro HPP occurred due to a Soviet counter-offensive.

"In the spring [of 1943], the Germans started mining, and in the early autumn, this work accelerated. Again, there are confirmed facts that before the explosion on October 14, they drained the water from the upper basin. In other words, they did what they had done in 1941 - they lowered the water level. When the Soviet troops crossed the outer defensive circle towards Zaporizhzhia, the Germans blew up part of the dam. But the Germans blew up a much smaller part than the Soviet troops," says Vladimir Linikov.

The reconstruction of the Dnipro HPP began after World War II, in 1947-1950.

A great transformation of nature: the construction of the Kakhovka HPP

In a commentary for Svidomi, Oleh Bazhan, a historian and senior researcher at the Institute of History of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, says that the construction of the Kakhovka HPP was part of the "Great Plan for the Transformation of Nature", formulated in a joint decision of the Council of Ministers of the USSR and the Communist Party Congress of October 20, 1948.

"It was a massive programme to regulate nature and change the climatic conditions in large parts of the Soviet Union to increase crop yields. The plan was designed for 1948-1965 and included the creation of several large forest strips and the construction of reservoirs,"

he says.

A whole cascade of reservoirs was created in southern Ukraine to combat drought and promote economic development in the region.

"There was also the issue of creating a power plant, as at that time there were also plans to build new factories in southern Ukraine, so there was a great need for electricity," says Oleg Bazhan.

On September 20, 1950, the USSR Council of Ministers adopted a resolution on constructing the Kakhovka HPP and the North Crimean Canal, intended to supply energy to Crimea.

"There is a belief that Stalin allegedly considered the construction of the Kakhovka reservoir to be a military and strategic objective. That is creating an artificial water barrier in the event of large-scale military operations in the future. I have not seen such data in the archives. The main purpose was to generate electricity for the production needs of southern Ukraine and Crimea," says Oleh Bazhan.

The construction of the Kakhovka HPP was a large-scale process involving people from all over the Soviet Union. According to the historian, Soviet propaganda promised construction workers "big profits", but their salaries were delayed, and they complained in private letters about malnutrition and difficult construction conditions.

The creation of the Kakhovka reservoir, necessary for the hydroelectric plant, involved flooding 29 settlements. The reservoir occupied the territory from the village of Kozatske, eight kilometres from Kakhovka, and ended near Zaporizhzhia.

"The creation of the 'bowl' of the Kakhovka reservoir was accompanied by a campaign to relocate people from these settlements to new areas. We can say that 37,000 people were partially or completely resettled. But this resettlement was not fully thought out because there was not enough money for transport services, for paying the costs of moving buildings, for rebuilding in a new place, and there was no way to buy enough building materials," says Oleh Bazhan.

The resettlement occurred within the Zaporizhzhia, Dnipropetrovsk and Kherson regions and did not involve moving the population to new territories. It was a matter of moving from the left to the right bank of the Dnipro.

Was there a chance to save the Grand Meadow?

When the Kakhovka reservoir was built, an area of vast floodplains called the Grand Meadow was flooded.

"Due to the flooding, the historical area belonging to the Zaporozhian Sich was lost. Five Zaporozhian Sichs were submerged: Tomakivska, Bazavlutska, Mykytynska, Chortomlytska and Pidpilnenska or Nova. The island of Mala Khortytsia was also damaged," says Oleh Bazhan.

The historian explains that Communist Party documents do not indicate that the issue of preserving these territories as historical values was not raised by the Party leadership.

As early as 1941, the Institute of Archaeology of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR organised an expedition to study the monuments of the Zaporozhian Sich, which concluded that it was "completely inexpedient to study the Zaporozhian Sich archaeologically" due to "poor preservation".

"In 1951, an expedition of two historians was formed to study the monuments of the Zaporozhian Sich. However, it should be remembered that the ideological component was at work then. At that time, the subject of the Cossacks was not popular. Therefore, there was no qualitative research question," explains Oleh Bazhan.

This area was underwater for about 70 years. After the Russian troops blew up the dam of the Kakhovka hydroelectric power station in June 2023 and the water came out of the reservoir, archaeologists had the opportunity to explore the territory of the Grand Meadow and the places where the Sich had been. Archaeologists are conducting research in areas where the security situation allows it.