Sudan: a country of many wars

Private property, two-storey building. This is a diplomatic mission of another country with a population of about 40 million people and a war going on. No, this is not the Ukrainian embassy abroad, but the Sudanese embassy in Ukraine. And despite this analogy, the Russian full-scale invasion and the Sudanese war could not be more different.

You most likely heard about the latter in April 2023, when it began. Although it has since disappeared from the headlines, it has not ceased. The attempted coup d'état has transformed into a protracted confrontation. It is difficult even to define what kind of war it is. First and foremost, it is a struggle between two armed groups against each other, but also against the Sudanese democratic project as a whole.

How did it come to this? Why have wars in Sudan been ongoing almost non-stop since independence? And what are Russia's interests in the country? To answer this question, we should first consider the history of Sudan.

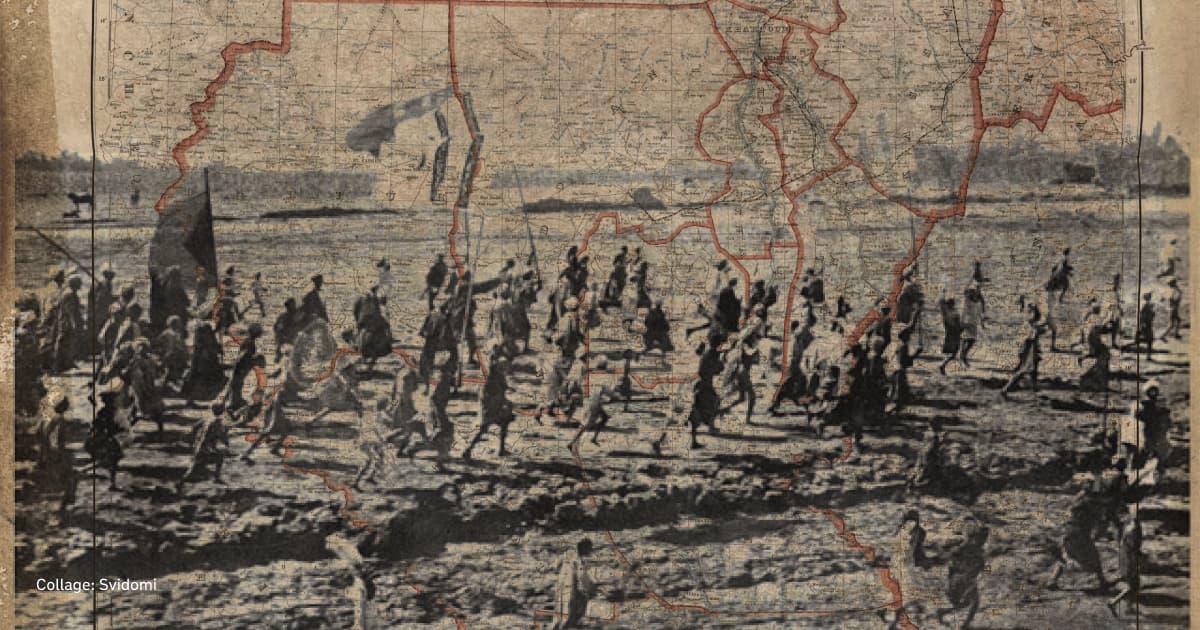

Sudan as a frontier

Sudan is a country in northwestern Africa. To the north, it borders Egypt, which has long considered this country its sphere of influence. If anyone has ever been to the south of Egypt and visited Abu Simbel Temples, they can roughly imagine how hot it can be in Sudan. In 1961, Polish reporter Ryszard Kapuściński visited the capital of the newly created Sudan and almost fainted from the heat.

"I felt that I couldn't go on, but I also knew I didn't have the strength to return. I started to panic, and I was sure that if I didn't find shade now, the sun would kill me," he wrote about his visit to Khartoum, the capital of Sudan. In June 2023, the temperature in the city reached 41 degrees. However, this did not stop the enemy from fighting for the streets of Khartoum, where Kapuściński once walked.

Sudan has an area of 1.8 million square kilometres. It is three times the size of Ukraine, nine times the size of Great Britain or twenty-two times the size of the Czech Republic. A country of this size cannot be ethnically homogeneous. However, Sudan has always been a frontier territory where different cultures clash. In the tenth century, an unknown Persian geographer wrote The Regions of the World from East to West. He mentions a "small province of Tari" with two Christian monasteries.

Jana Eger, an archaeologist at Freie Universität Berlin, suggests that this is the area on the border of two regions of Sudan — Northern State and Northern Kordofan (Šamāl Kurdufān). The ruins, which probably belong to the monastery, are located in the heart of the country. As of the tenth century, it was here that the frontier between two cultures - Egyptian Muslim and Nubian Christian — was located.

Over time, this border moved further south. Today, Islam is the dominant religion not only in Northern but also in Southern Kordofan. This is primarily the result of several hundred years of raids by Muslim Arabs from Egypt to the south. The Arabs were convinced that slavery was the most effective tool for converting to their religion. The fear of slavery would push people to accept Islam. They were partially successful, as the tribes of northern Sudan did indeed convert to Islam, and having Arab ancestors in the family was considered a sign of prestige. At the same time, the peaceful spread of Islam should not be ruled out.

Sudan as a colony

The result of these raids was described by the traveller Samuel Baker, who visited Egypt and Sudan in 1861:

"Every family in Upper Egypt and the Delta (of the Nile - ed.) depends on slave labour. Enslaved people cultivate the fields of the Sudan. Slaves take care of women in the harems of the rich and middle class. Poorer Arabs also want to own slaves. In fact, Egyptian society without slaves is like a cart without wheels: it cannot go anywhere."

The second half of the nineteenth century was a time of decline for the Ottoman Empire, under whose formal protectorate the Egyptian khedive stood. For example, there were uprisings in Crete in the sixties, the Balkans in the seventies, and the Sudan in the eighties. As a result, the first Sudanese state emerged, headed by the religious leader Muhammad Ahmad, who proclaimed himself the harbinger of the second coming of Christ. Therefore, this state was built around both religious and proto-national identities.

Meanwhile, the British took advantage of the uprising in Egypt and captured it. They did not stop there, and in 1884, they started a war against Sudan with the Egyptians. In 1885, Ahmad was killed, but even after that, the uprising did not stop. The British managed to destroy the Sudanese state only in 1889. They also desecrated the grave of the uprising leader.

Towards the war's end, Winston Churchill arrived in Sudan, serving in the British army as a press officer. At first, he portrayed Muhammad Ahmad in typical Orientalist terms — as a savage and barbarian. But later, he radically changed his point of view: in his book The River War, he called Ahmad a "noble man", a "priest, warrior, and patriot". And in 1931, he romanticised the leader of the Sudanese uprising, saying that his life was a romance in miniature.

Among other things, Churchill emphasised that Ahmad contributed to the liberation of enslaved Sudanese people by turning them into soldiers. The British were generally not happy with the economy built on the slave trade, but they did not want to transform it. On the contrary, they tried to reinforce the existing fissures in Sudanese society, particularly between the south and the north. They specifically restricted the activities of Christian preachers in the north and prevented Islam from spreading organically in the south.

Sudan as a nation-state

The results of these policies became apparent after the collapse of the British Empire. In the early 1950s, Sudan was still London's largest African colony. The story of its liberation is linked to the Egyptian state, as formally, London and Cairo jointly owned Sudan. At the time, the Egyptians could not free themselves from the British presence at the negotiating table. Sudan was the issue that blocked these negotiations. Egypt insisted that Sudan was part of the country, while the British feared that including Sudan would strengthen Cairo too much. Former U.S. Secretary of State Robert McNamara considered Egyptian demands one of the biggest mistakes in British-Egyptian relations.

However, in 1952, military officers seized power in Egypt and chose an anti-colonial course. They compromised on the Sudan and, in February 1953, agreed with the British that Sudan would have the right to determine its future. The Egyptians believed that the Sudanese would want to unite.

This was the beginning of the process of Sudanisation, i.e. the transfer of executive positions previously held by the British to the Sudanese. In addition, elections were held in 1953. Representatives of the empire were unhappy with the speed at which they lost control. An adviser to the British Governor-General, William Lewis, complained: "they (the newly appointed Sudanese - ed.) don't know how a government works", meaning how they could be appointed to political positions.

However, Egyptian representatives failed to play a subtle diplomatic game around the Sudanese issue. On the one hand, nationalist Egyptians did not understand why Cairo supported the Sudanese right to self-determination rather than advocating unity. On the other hand, the Egyptians' involvement in the process of Sudanisation and proposals for the country's future radicalised Sudanese supporters of independence. In addition, in 1955, an uprising of army units in the country's south began due to the fear of northern domination. It failed, but it pushed northern politicians to declare independence.

The British ambassador understood the reasons for the uprising. Writing about the principle of forced separation of Southerners and Northerners, he noted: "Of course, we are not solely responsible for the past [...]. But for 50 years, for two generations, we were in charge, and the policy that inspired our stewardship during that period cannot be left out of account".

Since then, the struggle between the rather artificially constructed identities of "Sudanese-Arabs" from the north and "Sudanese-Africans" has been going on almost continuously. It also involves several foreign players — the Soviet Union, West Germany, and Israel.

In fact, the differences between them are not that significant, and in general, there are people with darker skin in the north than in the south. There are also many Muslims living in the south. However, as the anthropologist Sondra Hale writes, 40 years of war resulted in artificial rifts between the south and the north.

This saga ended when South Sudan, thanks to US lobbying, became an independent state, a member of the UN, and thus a full member of the international community. Since 2011, South Sudan has been the youngest country in the world. Despite the support of Western countries, the civil war between the state and some rebel organisations continued in South Sudan. It is still ongoing, although the intensity of the fighting has significantly decreased since 2020.

The UK Secretary of State for International Development, Rory Stewart, described the situation in the newly created country as follows:

"I was worried about the South Sudanese government’s request for us to rebuild the same building the US had financed in 2005, South Sudanese opposition forces looted and vandalised in 2013, the Japanese rebuilt in 2014, and government forces razed to the ground in 2015."

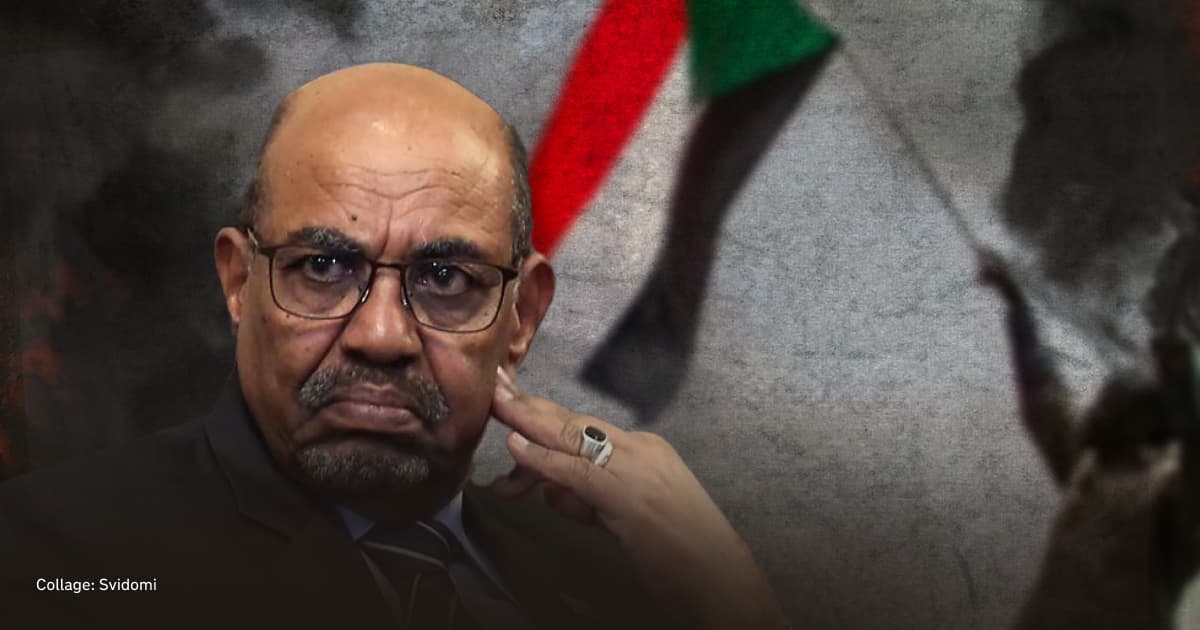

However, the separation of South Sudan into a separate state did not end the war in Sudan. On the contrary, opening another front in the country prevented the authoritarian ruler Omar al-Bashir from waging war in the south. We are talking about Darfur (Dār Dājū).

The conflict in Darfur

"Dar" means "home" in Arabic. The Furs are the largest ethnic group in this region, but not the only one. The area lies in the west of Sudan. Like those in South Sudan, its inhabitants believed they were being unfairly treated and economically exploited by the power elite from the north of Sudan.

The conflict in Darfur did not start yesterday either. As early as the sixties, after the Declaration of Independence, political groups emerged that opposed the privileged position of the Jellaba ethnic and class group. These are people from northern Sudan and the basins of its main rivers. During the nineteenth century, these people used to trade in slaves recruited in Darfur, among other places.

After Sudan gained its independence, the Jellaba benefited from the funds allocated for the region's development. This happened because ethnically related Jellaba Arabs from northern Sudan concentrated power in local authorities in Darfur.

The historian Rex Sean O'Fahey described this system as follows:

"When I first went to Darfur in 1969, I recognised this fact of a quasi-colonial administration ... all were very much Northern: an officers' club, a civil servants' club, khaki uniforms everywhere, a beautiful open-air cinema owned by the Greeks. One governor apologetically handed me over to his deputy as he was about to go on holiday to hunt foxes in Dorsetshire (a rural region in England known as one of the best places for fox hunting - ed.)”.

In 1981, the Fur movement succeeded in getting a member of this group appointed to the post of head of the region for the first time in 60 years. This led to polarisation: the Fur actively opposed the Zaghawa (nomadic Arabs) and vice versa.

In addition, environmental conditions in Sudan began to deteriorate. Due to the drought, migrants from other regions began to arrive in Darfur, but the furs, mostly settled farmers, did not want to give them access to land or water. Eventually, in the mid-eighties, the conflict turned armed.

These events were described by Sudanese anthropologist Sharif Harir: "Under the immense pressure, the Furs took drastic measures to protect their interests. They resorted to setting fire to pastures on a large scale, aiming to compel the Arabs to relocate to alternative grazing lands. Additionally, they attempted to restrict access to water sources. In response to the Arabs’ theft of their cattle, the Furs reciprocated in kind. The situation escalated further as the Arabs retaliated by setting fire to Fur villages and farms, uprooting trees in orchards, and causing destruction to essential farming equipment such as pumps, ploughs, and trucks."

Over time, the conflict has evolved. While initially resource-based, it eventually became a struggle based on identities and ideologies. This is how the concept of janjaweed (Janjawīd) emerged. It is used to refer to Arab armed groups that attack the Furs.

In 1989, the conflict was brought to a halt at the non-governmental level, in particular through a series of roundtables. Direct violence became less intense, but the confrontation did not disappear. In the early twenty-first century, the Second Sudanese Civil War slowed down. Washington hoped that the war would finally end in Sudan. Meanwhile, the situation in Darfur was getting hotter again.

It is difficult to name a single event that started the war. It is often pointed out that in 2002, Fur armed groups carried out a series of attacks on the barracks of the Sudanese armed forces. However, this dramatically simplifies the picture of the confrontation, which was never fully resolved.

Moreover, the armed conflict that began in 2002 was not purely ethnic. Instead, it started due to the confrontation between the population of Darfur and the authoritarian regime of al-Bashir (al-Bashīr). Several Arab tribes refused to side with the state; some even joined forces with the Fur.

To suppress the Darfurian resistance, the regime began to strengthen Janjaweed groups. They were recruiting "prisoners, former members of the Islamic Legion (an Islamist group sponsored by Muammar Gaddafi - ed.), former military personnel, the Ansar (followers of Muhammad Ahmad - ed.), criminals and landless nomads from North Darfur".

In October 2002, the Janjaweed launched a significant offensive against Fur communities. As a result, a 12-year war broke out between the Janjaweed-led state and the Fur rebels. This war was genocidal.

"Have you ever seen a cell so full that the door cannot be closed? To close the door, they (Sudanese military - ed.) would put a Toyota Land Cruiser by the door, close it themselves as much as they could, and then the car would push the door until it was completely closed."

"My aunt was wounded by a piece of shrapnel from an Antonov bomb (the Sudanese military used Soviet An-26 aircraft as bombers - ed.) Three other people were killed immediately, but she survived. [...] Their bodies were torn apart, and many body parts remained hanging from the tree branches."

These are the recollections of several Furs who witnessed the events.

The total number of people who died as a direct result of the violence, as well as as a result of hunger and disease, has not yet been established. However, the number runs into hundreds of thousands of people.

Sudan as a Russian interest

Sudan's aviation uses aircraft manufactured in the Ukrainian SSR. There were periods when the Kremlin maintained good relations with the country and provided weapons. However, this has not always been the case, which is again related to Egypt.

After the 1952 revolution, the Soviet Union began to provide significant assistance to the country because of the anti-Western orientation of the new government. However, the defeat in the Six-Day War against Israel in 1967 and Nasser's death in 1970 changed the situation completely. The following Egyptian leader, Muhammad Sadat, was suspicious of the USSR. His views were shared by a large part of the military, as Soviet "advisers" followed officers and even demanded the execution of those accused of the 1967 defeat. In a letter to US President Richard Nixon, Sadat wrote: "we are not within the Soviet sphere of influence nor, for that matter, anybody's sphere of influence". During his time, relations between the USSR and Egypt deteriorated significantly.

In Sudan, then, the regime of Gaafar Nimeiry was quite friendly to the USSR. Although he received weapons from the USSR, he fought against the Communist Party of Sudan. In 1969, Nimeiry visited the USSR and offered to maintain good relations despite all this. However, the Sudanese leader did not know that the KGB considered the Sudanese communists extremely reliable. After Egypt's foreign policy transformation, the Kremlin had to get back at him. In 1971, a group of Sudanese military and communists attempted to seize power but were defeated. This worsened relations with Moscow.

They were restored only after Omar al-Bashīr came to power in the nineties. The relationship reached unprecedented levels after Putin's transfer from the FSS to the Kremlin, as Russia supported Sudan's wars in the south and Darfur. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, since 2001, Russia has supplied Sudan with more than $985 million worth of weapons. In return, Sudan joined a small club of countries recognising the temporarily occupied Crimea (Qirim) as Russian territory. In addition, Sudan was a launching pad for Russia to spread its influence in Africa and the Middle East, thanks to its port in the Red Sea.

Finally, it was not only Russia that supported al-Bashīr. Under Yanukovych, Partiia rehioniv (the Party of Regions) also tried to increase arms supplies to Sudan under the guise of a Ukraine-Sudan Agreement Concerning Cooperation in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space for Peaceful Purposes. The agreement was not ratified, but Ukrainian weapons worth $226 million were delivered to Sudan in 2010-2013. According to the Stockholm Institute, in 2010, they set a record by selling about 190 tanks, which is why they outsold Russia, China and Belarus combined.

In 2013, the war intensified again, so the al-Bashīr regime decided to institutionalise the Janjaweed, turning them into a Rapid Response Force. Since then, this armed group, independent of the army, has existed as a separate political force. It is led by Mohamed Dagalo (Muẖammad H̱amdān Daqlū), generally referred to mononymously as Hemedti. He and his unit have been directly involved in war crimes in Darfur.

As Kholood Khair, an Oxford graduate, founder, and Director of the Confluence Advisory think tank, explains in a commentary to Svidomi, Hemedti has developed his political project.

"He wants to copy the state model that underpins the United Arab Emirates - a monarchy with a strong economy and a large extractive sector. After the independence of the South, Sudan lost a significant part of its oil and gas reserves. Therefore, the focus shifted to gold mining. The extraction of this resource is more decentralised, so non-state actors can better manage it than the state. Namely, Hemedti and his partner Yevgeny Prigozhin," says Kholood Khair.

Earlier, Svidomi has already told how the owner of the Wagner PMC extracted gold in this country.

The gold business is not the only thing uniting Prigozhin and Hemedti. The social composition of the Janjaweed is somewhat reminiscent of the Wagner PMC militants. Their methods of warfare are similar, in part because the Wagnerians have been conducting training for the Rapid Response Forces since 2017.

Sudan as a victim of coups

In 2019, a coup d'état took place in Sudan. The army deprived Omar al-Bashīr of the power he had held for 30 years. Protracted protests in the capital preceded this. The political climate for Russia has deteriorated, and the project to create a military base for the Russian navy has been suspended.

After the arrest of al-Bashir and his allies, the military formed the Transitional Military Council. At the same time, the protests did not stop: the Sudanese protested not to replace the dictator with a military junta. Rapid response forces dispersed the protesters, killing more than 100 people. Eventually, the military agreed to share power with civilians. This formed the Transitional Sovereign Council and set a timetable for the democratic transformation of the country's political system.

However, this plan failed to materialise: another coup d'état occurred in 2021. The military arrested civilian officials this time, including Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok. He was later released and even reinstated, but Hamdok resigned because he did not want to be associated with the military regime. The Transitional Sovereign Council still exists, but after the 2021 coup, it became more controlled by the military.

Elections were scheduled for the summer of 2023. Members of the Transitional Sovereign Council are not eligible to run for office. At the same time, Army Commander-in-Chief Abdel al-Burhan and Hemedti did not plan to give up power. Moreover, Burhan, like Hemedti, had his political project. While the Janjaweed leader focuses on the UAE and monarchism, Burhan cooperates with Egypt and promotes political Islam.

Analyst Khair believes that the conflict between the two groups has been evident for a long time. "Even when they organised the 2021 coup together, Hemedti was already demonstrating political separateness — he did not speak out in support of the coup for a long time and then spoke cautiously," she says.

That's why a war broke out between Burhan and Hemedti. "The political changes in the country after the fall of the al-Bashir regime have reached a dead end," she explains. "These two armed groups simply do not know how to solve their problems in any other way. They fear democratisation because they may be held responsible for the blood on their hands."

The current conflict should not be considered a secret game of foreign powers. Both sides may receive assistance from specific forces, but it is not decisive. As Sudan's history demonstrates, these political players have enough reasons to fear and hate each other without external interference. Although Burhan tried to hide it, his army received help from Wagner, just as the Jandaweed did.

At the same time, Wagner has a strategic interest in the Hemedti's group. It has the most power in the country's west, in Darfur. This region borders on Chad, a country where the rebel group Front for Change and Concord in Chad, or FACT, exists. This group received assistance from PMC. In early 2023, the Wagnerians continued to train other groups.

"Therefore, access to the Sudanese-Chadian border can be quite valuable for PMC," explains Khair.

Moreover, Hemedti has already demonstrated his value to the Kremlin on another border - with the Moscow-controlled Central African Republic. In January 2023, he blocked the border to prevent rebels from overthrowing the CAR regime. So if the Russians eventually establish a loyal regime in Niger and Chad, the Kremlin will have a belt of friendly African states, from Mali to western Sudan.

When considering these international political schemes, we should not forget about civilians in Sudan, as they suffer the most from the current war. On the one hand, many Sudanese dream of seeing the demise of the Rapid Reaction Force, which is responsible for crimes in Darfur. On the other hand, the price of such an outcome may be too high: another civil war and further consolidation of power in the hands of the military. Neither is conducive to building democracy in a country in permanent war for the past 60 years.

This war is now in its seventh month. The United States, Saudi Arabia, and the East African Intergovernmental Authority on Development have been mediating between the army and the Janjaweed. Still, it is unclear what the outcome might be. Burhan and Hemedti will not be able to stay in the same country because there will always be a so-called "security dilemma" between them.

So the war is going on. This situation is favourable for Russia because even if al-Burhan wins, the Kremlin will find common ground with an authoritarian leader unlikely to have other allies.

Khair does not lose hope for the possibility of further democratic transformation. Despite the war, Sudanese civil society, which sparked the 2019 revolution, is still in the game. The only question is whether the mediators will hear their voices.