Who created the label about the Great Patriotic War?

Let's open a textbook on the history of the USSR for 4th graders, published in 1951. It reads: "The entire Soviet people, at Stalin's call, united to win the Great Patriotic War." Now, we open the textbook "Introduction to the History of Ukraine" for 5th graders, published in 2010. It reads: "The Great Patriotic War began in June 1941, and the Soviet troops showed heroism but retreated." There is no unbiased way to measure heroism. It will suffice to give the following estimate: Mark Edele, the inaugural Hansen Professor in History at the University of Melbourne, believes that in 1941, 4-6% of all Soviet soldiers in German captivity surrendered of their own free will. This is 100-200 thousand people.

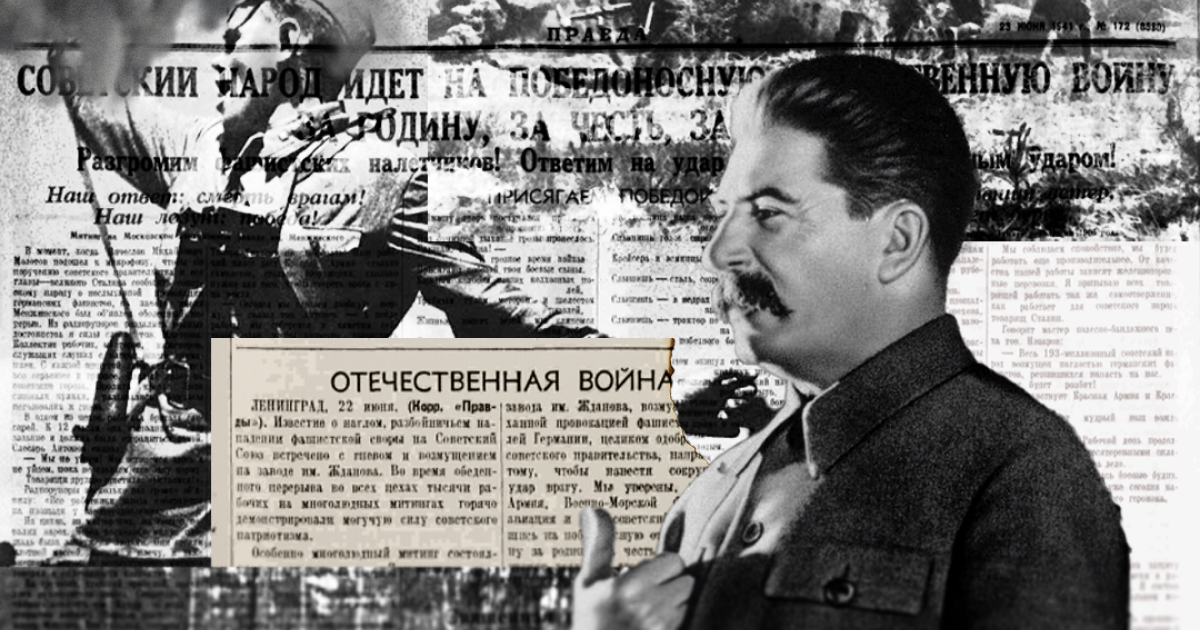

The Great Patriotic War was a label created quickly by Soviet propaganda. It was meant to convince people that these hundreds of thousands did not exist. That all the citizens of the USSR had united against Germany. It didn't matter that some people had only received Soviet citizenship shortly before these events when the Soviet Union seized the western Ukrainian and western Belarusian territories and the Baltic states. Who made up this myth?

The need for history

The twenties of the twentieth century in the USSR were both a time of deficient socio-economic development and experiments. The economic devastation resulted from Bolshevik policy and years of continuous warfare. For example, if all the arable land in Podillia were distributed among the region's peasants, each person would have 0.92 hectares, slightly less than St. Sophia's Square in Kyiv. However, this would not be enough.

The low level of technology meant that a peasant would have needed at least 1.1 tithes to support himself. At the same time, just a few hundred kilometres away, in Kyiv and Kharkiv, artistic life was booming, bringing the most avant-garde works to Ukrainian culture. But their authors also lived in poverty. The playwright Mykola Kulish worked as a school inspector, did not have his own home, and lived in a home for juvenile delinquents.

It was a time of experiments not only in art but also in science. Communist Party historians sought to construct a history of a people without a nation, portraying it as an endless chain of episodes of peasants' struggle against various oppressors. In such a history, none of the Cossack hetmans can play a positive role, not even Bohdan Khmelnytskyi, who agreed with the Tsardom of Muscovy.

The Russian historian Yevgeny Tarle did not follow this pattern. And it is not surprising — he began his career in imperial times and had social democratic, not Bolshevik, views. This did not prevent him from being an empire servant. He called the Ukrainian People's Republic delegation to the Brest-Lithuania negotiations "unexpectedly and independently born" and wondered why other countries considered the UPR a separate state.

Tarle was popular with students at Moscow University, where he taught. They say no one had time to take notes because he spoke so quickly and poetically. He specialised in the history of France and thus in the Revolution and Napoleon.

And this topic is a key one for Soviet and Marxist history. Therefore, in 1928, the leader of the party historians, Mikhail Pokrovsky, criticised Tarle. This was due to both personal grievances and the escalating political situation. Stalin consolidated power, so repression intensified. This led to Tarle's arrest in 1930 by Soviet security forces on charges of attempting to seize power in the country. He was sentenced to five years' exile in Qazaqstan. This was a "minor punishment", as other defendants in the case were shot or sent to detention camps.

Tarle did not serve the whole sentence. He blamed his expulsion on other defendants in the case, who had slandered him, rather than on the authorities, although he had done the same during interrogations. While in Qazaqstan, the historian wrote letters to all the authorities asking for help. Eventually, in 1932, despite the resistance of the security forces, he was allowed to return to Russia.

Who was behind this decision? The answer is to be found in Tarle's book, published in 1936 and becoming his prominent bestseller, Napoleon. While working on the book, the historian wrote to his wife that Napoleon had been commissioned to him. The book's editor claimed that the "master" had promised to be the first to read it. The Soviet elite used to call Stalin this way. For example, this is evidenced in the letters of the French communist writer Henri Barbusse.

By then, Pokrovsky had died, and the Marxist anti-national school of history began to die with him. Stalin, who had finally concentrated all power, set out to strengthen Russian nationalism. For example, in 1937, during the most severe intensification of repression, the Ukrainian SSR and the Georgian SSR celebrated the anniversary of their national poets, Taras Shevchenko and Shota Rustaveli. At the same time, only Pushkin's anniversary was celebrated throughout the USSR, and the leading newspaper, Pravda, published an article on the occasion entitled "Glory of the Russian People".

In addition, classical Marxist concepts reject the role of the individual in history. For them, any personality, such as Napoleon or Stalin, is merely a product of current socioeconomic relations.

Tarle never shared these postulates, so he openly admired the figure of the French leader. In addition, after being penniless in exile (the academician used to eat the head of a camel), he was "broken" and ready to cooperate with the authorities. So, he became a participant in a significant ideological transformation: the cult of the individual, the rise of Russian nationalism, and the Soviet state's return to history as a source of its legitimacy.

Patriotic: small and great

Most Russian historians refer to the French army's campaign against the Russian Empire as a "patriotic war". Pokrovsky rejected this notion. Tarle, on the other hand, used it. He devoted his next book in 1938 to this war. The historian fills his work with Russian nationalism, phrases like "the Russian people defended themselves, defeated someone who could not be defeated," "the Russian people mortally wounded Napoleon," and so on. In other words, the book was written not for a professional audience but for propaganda.

It was so popular that it was reprinted every year. In particular, in 1941, after the outbreak of the German-Soviet war. Despite all the attempts of Soviet propaganda to present this war as unexpected and unanticipated, Soviet intelligence officers and the Kremlin were well aware of the concentration of the German army. On the eve of the invasion, German reconnaissance planes flew into Soviet airspace on a daily basis. However, on June 14, Soviet propaganda continued to write that Germany was not planning an attack and that reports about it were enemy propaganda.

Therefore, when the Germans began to advance, no one among the Soviet leadership had ready answers. Pravda, published the night before the invasion, did not contain information about the war. Therefore, someone had to announce it on the radio. Stalin did not want to do this, so the responsibility fell to the head of Soviet diplomacy, Vyacheslav Molotov. It was then that he first called the war "patriotic" and compared the resistance of the Soviet people to the way the subjects of the Russian Empire repelled Napoleon's attack.

As of noon on June 22, Molotov could not have had any information about the actions of Soviet citizens. He also did not write this metaphor — it is not in the draft of the speech. Molotov claimed that Stalin had edited the text. In any case, Tarle's influence is evident.

On the same day, Yemelyan Yaroslavsky, a veteran Bolshevik close to Stalin, deepened this metaphor for the June 23 issue of Pravda. At the time, Yaroslavsky did not hold any influential positions and was engaged in writing propaganda materials. In his text, he added "great" to "patriotic". This is not surprising, as the material is written in the style of the Stalinist Empire. It praises the "Russian people" who always defeat their enemies.

However, these metaphors do not match reality. At the time, Stalin did not believe in war and hoped for a diplomatic solution. On June 23, he even sent his trusted translator, Vladimir Pavlov, to the German Embassy, which had not yet left Moscow.

(Un)accidental parallels

The German and French invasions have something in common. For example, in 1807, Napoleon signed the Treaties of Tilsit with Russian Emperor Alexander I, and a few years later attacked the empire. The same happened in the case of the Soviet-German non-aggression pact and the subsequent war.

In addition, during the initial phases of both wars, Russian and Soviet troops retreated due to their failure to be prepared for combat. However, the Russian Empire, unlike the Soviet Union, did not have such a powerful propaganda complex. While in evacuation, Tarle tried to justify the Soviet defeats by saying that the Kremlin was following the strategy of Mikhail Kutuzov, commander of the Russian Empire's troops in the war against Napoleon. The Red Army was supposedly retreating to defeat the Germans in a counter-offensive. This is how Stalin justified the losses of the first years of the war after its end.

However, on the morning of June 22, the Soviet leadership did not yet understand these parallels. They could not remain silent; they had to explain the war somehow. They fell victim to the "heuristic of accessibility". This trap of reasoning works like this: if an example comes to mind, it is the best fit. Tarle's repeated reprints influenced the thinking of Stalin and his entourage, which is why the "Great Patriotic War" concept emerged. Over the next 70 years, propaganda reinforced it. This is how a random and not too well-developed thought became the only "correct" way of thinking.