What is genuine Ukrainian culture, and how has Russia distorted it?

Since the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion, Ukrainians have primarily turned to their traditional culture, such as holding Vechornytsi (evening parties), celebrating Christmas in a conventional way, or learning about the history of embroidered shirts.

Svidomi talked to Yaroslava Muzychenko, a senior researcher at the National Center of Folk Culture "Ivan Honchar Museum, about traditional Ukrainian culture, Ukrainians' perception of this culture today, how Russia has distorted it, and how to get back to our roots.

The concept of traditional culture

Yaroslava Muzychenko explains that in Europe, modern nations began forming identities based on traditional cultures in the nineteenth century. Folklore, customs, formal and family rituals, folk dress, and cuisine are part of the conventional culture that distinguishes one nation from another. It helps different peoples to demonstrate their separateness, but at the same time, different cultures can have common features.

"There are similar elements in the celebration of Christmas in almost all European nations, and each nation has its peculiarities. The complex of these features, consisting of folk festivals, art, dress, songs, fairy tales, etc., is the traditional culture of the ethnic group, ethnographers record," Muzychenko explains.

Ukrainian traditional culture was formed over thousands of years. It includes not only Slavic traditions but also elements of the cultures of the tribes and peoples living on the territory of Ukraine before. Thus, there are traditions in Ukrainian culture that date back to the Neolithic period, such as pottery.

The situation with Ukrainian culture during the Soviet period

Yaroslava Muzychenko explains that during the Soviet period, traditional Ukrainian culture experienced several waves of transformation. The authorities left a distorted national form in which they put the content necessary for "communist education." The first one took place in the 20s of the XX century.

The scholar explains that in the 1920s, the Soviet government allowed the celebration of Christmas but called it "Komsomol Christmas." Back then, carolers went from house to house of the people loyal to the authorities with a five-pointed star, and instead of receiving Christmas treats, they brought gifts to their hosts.

Another indication that the Soviet government was replacing traditional Ukrainian culture is the disappearance of kobzar and lira singing and the spread of bandura chapels. The researcher adds:

In the 30s of the last century, 'uncontrolled' kobzars stopped going to villages. Those who remained after the Holodomor and repressions began to gather bandura players in chapels, who sang songs about the Communist Party from the stage. These songs were called "folk songs," and their list was strictly censored,

The Holodomor of 1932-1933 also had consequences for Ukrainian culture, as people had no time for celebrations after it. Moreover, the Soviet government also fostered a dismissive attitude toward traditional holidays.

"For example, people were especially forced to go to volunteer clean-ups on Saturdays or Sundays to do dirty work at Easter, Trinity, and other holidays. Churches were closed for worship; instead, they were used as dance clubs or household warehouses," adds the scholar.

Cities were cleansed of any manifestations of Ukrainian culture while carrying out massive Russification: schools and higher education institutions were pushed to use the Russian language. In villages, elements of folk festivals, songs, and the Ukrainian language were allowed, however, to create an image of Ukrainian culture's inferiority.

Yaroslava Muzychenko says that during the next wave of transformation in the 1960s, the Communist Party Congress decided that scientists, especially ethnologists, should "take care" of changes in people's minds. Therefore, the Ukrainian SSR Council of Ministers created a commission to create new holidays and rituals and ethnographers were tasked with figuring out how to use folk culture to benefit the "party."

"They developed scenarios and guidelines for' properly' celebrating holidays. These instructions were handed over to clubs, "houses of culture," and schools. This process was covered by the media, which at that time depended on the state apparatus and was controlled by," the researcher says.

At this time, a collective image of a "Ukrainian woman" in a wreath with ribbons and a corset and a "Cossack" in shiny blue or red pants were formed, as well as a "Hutsulka and Hutsulyk," representing Ukrainians. Choirs and dance groups performed in this " solely correct" attire, performing the repertoire approved by the authorities. Muzychenko explains:

As a result, younger generations developed a dismissive attitude toward Ukrainian culture. For them, it was ridiculous, incomprehensible, untrue, and unnecessary

However, at that time, some centres managed to preserve traditional culture. For example, in Kyiv, it was the house of the artist and sculptor Ivan Honchar, where he created a museum of Ukrainian folk culture.

"Gonchar fought in the Red Army during World War II, travelled with the troops to European countries and saw European museums and art schools. I was amazed at how other countries honour their culture. When he returned home, he noticed a difference: in "Soviet" Ukraine, national art was destroyed, isolated from society, or devalued. So the artist began travelling around Ukraine and collecting folk art, ancient icons, and photographs of Ukrainian families in traditional costumes," the researcher says.

Ivan Honchar used his sketches and photos to create 20 craft albums describing different regions of Ukraine and individual villages and towns.

"In Honchar's house, Ukrainian ethnic culture was forged into a national culture. It was the centre of the Ukrainian Sixties movement, a civic and artistic phenomenon in world history. For example, Alla Horska, a sixties artist, human rights activist, and public figure, visited the city for the first time and began to study the Ukrainian language (she was a Russian speaker) and folk art. As a result, her work changed, became bright, original and national", - explains the museum employee.

The revival of Ukrainian culture and the war

In 1989, as the pressure of the totalitarian state weakened and the Ukrainian liberation movement grew stronger, folk culture began to revive.

"During the first years of independence, the subject of 'Folklore' was introduced in schools, and a large number of magazines and research papers on traditional culture appeared," Muzychenko says.

The process stopped in the late 1990s when Russia began to influence cultural processes in Ukraine again. The scholar says:

A large amount of literature imported from Russia appeared, which formed a pseudo-patriotic attitude toward culture. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian state has stopped allocating funds for the publication of ethnographic books and magazines

In 2005, there was a new cultural "outbreak" when embroidered shirts became fashionable, and some Ukrainian stars began to organise festivals, such as Oleh Skrypka's Kraina Mriy (Country of Dreams).

Muzychenko explains that the full-scale Russian invasion significantly impacted Ukrainians' attitudes toward traditional culture.

"Today, under the threat of destruction, Ukrainians are beginning to look for an explanation for why this is happening. Eventually, they concluded that Russia attacked to destroy our identity. Therefore, in response, Ukrainians search for their roots — cultural identity — to perceive and preserve themselves," the researcher says.

Ukrainians' perception of traditional culture and the influence of Russia

Even though Ukrainians are now beginning to learn about traditional culture, not everyone understands what is indigenous to it and what is imposed by Soviet/Russian policy.

"Ukrainians still congratulate each other on the Three Saviors, or Spas, (Savior or Transfiguration Feast is a Christian folk holiday of Eastern Slavs during which fruit, honey, and nuts are blessed in church - ed.). However, in Ukrainian traditional culture, there is only one Savior's Day, while in Russia, there are "three Savior's Days" - "honey, apple and nut". It is due to climatic conditions. In Russia, everything ripens later, and harvesting is still important, unlike Ukrainian reproductive farming. That's why the folk calendar is different there," the researcher says.

These narratives emerged in Ukraine because Russia has been "throwing" false information about Ukrainian rituals with Russian cultural elements into the Ukrainian information space for a long time.

"Every year before Masnytsia (Shrovetide), stories about pancakes with caviar and advertisements for "folk festivals" with samovars and bagels are spread. These are all Russian elements," the scholar explains.

"This is how Russia tried to keep Ukrainians in its cultural field.

How to preserve traditional culture?

According to Yaroslava Muzychenko, to preserve traditional Ukrainian culture, it is necessary to create high-quality scientific research and popularise it.

Civil society should pressure the state to request research on this very topic. Creating a complete sound archive of Ukrainian folklore, electronic catalogues of museum collections of folk art and interactive online atlases of ethnocultural phenomena. They should be made freely available to everyone, and we should develop educational programs on their basis.

"In such atlases, one could find information about what kind of clothing prevails in a particular region, what songs, fairy tales, and original rituals of calendar or family holidays originate from a particular region," says the researcher.

"Young people will then be able to sing authentic carols from their region, not unnamed songs they found on YouTube," Muzychuk emphasises.

The popularisation of traditional Ukrainian culture should be carried out in cooperation with scholars, civil society, and the state.

You need to invest in your own identity

How do foreigners perceive Ukrainian culture?

In addition to Ukrainians rediscovering traditional Ukrainian culture, foreigners also start to discover it for themselves.

"From what I see, foreigners like our language, rituals, and cuisine," Muzychenko says.

It is mainly due to Ukrainians being forced to stay abroad and open up Ukrainian traditions to other nations.

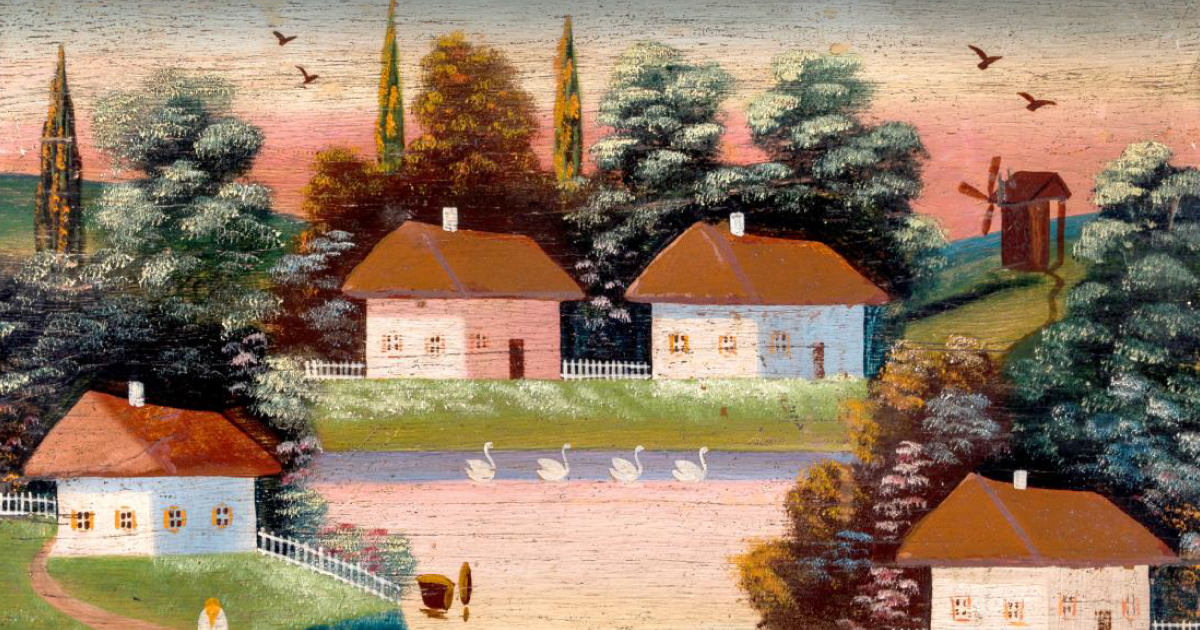

The following paintings were used for the cover:

«Over the Dnipro River» , nevidomyj/a, 1936, Kyiv Oblast

"Portrait of a girl wearing a flower crown", Jarmolenko Panas (1886 - 1953-05-20), Kyiv Oblast