The Chronology of the Arab-Israeli Confrontation: Where Did It Start and What Is Happening Now?

Ukraine is not Afghanistan or Vietnam. Ukraine is neither Israel nor Azerbaijan. The illegal armed groups of the "L/DPR" are not the Islamic Resistance Movement (Harakah al-Muqāwamah al-ʾIslāmiyyah, acronym - Hamas). Ukraine is Ukraine, and Ukraine is fighting for its survival. It might seem simple enough truth. However, these apparent circumstances go unmentioned in the context of social media, which encourages a mandatory choice of sides.

At the same time, this dynamic is logical. Over the past ten years, Ukrainians have become convinced that fighting for their right to life in the physical and information spaces is necessary. This is a fundamental characteristic of modern warfare. Therefore, all participants in any confrontation seek to sway global public opinion to their side, using digital platforms to build situational or even strategic partnerships.

For example, the Coalition of armed Tuareg groups has recently resumed participating in the Malian civil war and declared solidarity with Ukraine in the fight against the Wagner PMC. At the same time, the instantaneous dissemination of information also has negative consequences. In Ukraine, unnecessary disputes arise over whom to support in this or that confrontation. This was the case with the latest episode of the war over Nagorno-Karabakh. The same is happening now, during the next, albeit somewhat unusual, episode of the Arab-Israeli confrontation.

The past is a weapon. The past allows us to legitimise the status quo and justify the political project of the future. Accordingly, there is never only one interpretation of the past. However, this does not mean that we should not strive for unbiased knowledge.

The purpose of this text is not to justify the position of Israel or its enemy. Moreover, Ukraine at the state level and the vast majority of opinion leadership will support Israel regardless of how the past is portrayed. Instead, the online media outlet Svidomi wants to offer the reader a chronology of the Arab-Israeli confrontation so that the understanding of current events may be based on more than Telegram messages.

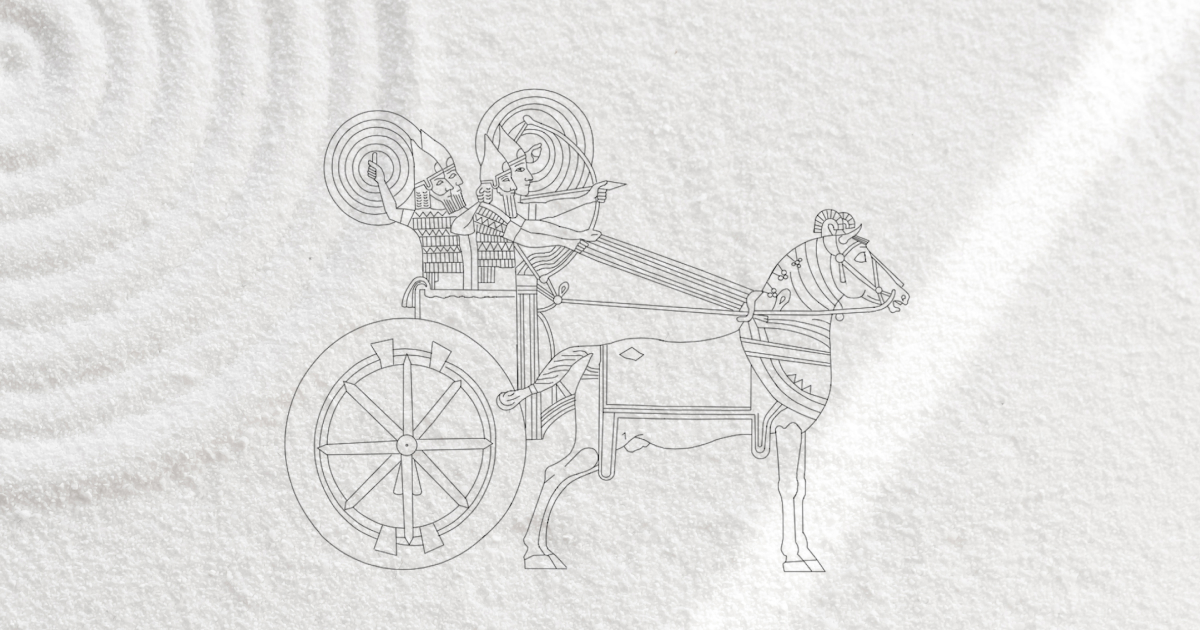

Pre-modern days

When the first tribes of Cimmerians arrived in southern Ukraine, local states, including the Kingdom of Israel, first appeared on the territory of modern Israel. During the twentieth century, various theories developed to explain its emergence: external invasion, peaceful penetration, peasant revolution, etc.

One way or another, the Assyrian state, centred in modern-day Iraq, gradually seized these lands and deported some Israelites. The rest of the Israelite tribes continued to live there and mixed with other local ethnicities. The region was captured by one ancient empire or another, including the Roman Empire. It played a key role in the history of the Jews. The Israelis raised several uprisings, and the empire responded with physical abuse and indirect violence, such as resetting people practising Judaism to other parts of the state, particularly in Europe.

These events are not directly related to what is happening in the region today. Like any other country, Ukraine has also seen bloody armed confrontations, uprisings, and expulsions of ethnic groups. However, these stories can later form the basis of narratives that can mobilise support and channel it towards political goals.

The British historian Keith Whitelam argues that the emergence of the kingdom of Israel was not a result of a single event but rather a complex process influenced by various factors, including political circumstances in which their authors worked. Thus, their task was to justify the present rather than to explain the past.

Modern times

The fundamental problem for the state in the system of international relations is survival. Without the state, this problem is transferred to a lower level — the community, the family, the individual. However, there is no other level above the state: no "adult" will take care of security. All nations face this challenge, not just Jews. Stateless peoples seek sovereignty, among other things, by shifting the security problem to a higher level — a state to trust.

During the nineteenth century, the elites of many European stateless peoples began to develop their ideologies of nationalism in parallel. This was also true of Jews living in Europe. They started to spread the Zionist idea, the doctrine of the need to create a Jewish national state.

As a result of the First World War and subsequent revolutionary wars, the empires that had been their home, albeit often a dangerous one, collapsed. Because of this and the growing anti-Semitism in Europe, Jews decided to move more and more often. Where did they go? To a region where very few Jews lived at the time (about 10-15%), which for centuries had been under the influence of Muslim culture and came under British control only after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. To Palestine, which was administered by the United Kingdom under a League of Nations mandate.

Any nation-state faces the same problem: its territorial boundaries do not coincide with its ethnic boundaries. In other words, there are always representatives of the state's ethnicity abroad, while within its borders, there are representatives of different ethnic groups. However, these difficulties rarely stop the establishment of new states.

For example, restraining Jewish state formation would have been impossible after the Second World War. On the one hand, it would have been unbearable for Jews to continue living in the cities of Europe where they had been ghettoised, robbed, and murdered yesterday. On the other hand, the British Empire never recovered from World War II and could not continue to exist in the long term. It was forced to balance Arab decolonising nationalism with the Jewish desire to come to Palestine.

The easiest way was to withdraw from the region. The legal prerequisite for this was the adoption of UN General Assembly Declaration 181 in November 1947, which allowed for the creation of Jewish and Arab states from the Mandate Territory and the transfer of Jerusalem under international control. This plan was never implemented, as Arab resistance began even before the proclamation of the state of Israel.

Later, neighbouring Arab states joined the war. However, they were defeated, so in 1948, Israel expanded its borders in contrast to those envisaged in the resolution. This happened again three more times - in 1956, 1967, and 1973.

Although there were significant differences between these wars, Israel maintained its dominance over the situation and continued to control territories not envisaged by the General Assembly resolution. This is the case, for example, with the Golan Heights, which has been under Israeli control since 1967. Before its seizure, there were no Jewish settlements in the region at all. The UN recognises the area as being under Israeli occupation control.

After the Yom Kippur War (an armed conflict between Israel, Egypt, and Syria – ed.) in 1973, Israel sought to normalise relations with Arab states gradually. But this does not solve the main problem: it is impossible to match legal and ethnic borders perfectly. There will still be Palestinians who are dissatisfied. And so it happens.

Both in the diaspora in neighbouring countries, where Palestinians arrived as refugees after Israel's independence, and in Palestine itself, several groups gradually emerged that refused to accept the current situation after the subsequent defeat of the Arab countries. Their ideology varied from Marxism in the sixties to political Islam in the eighties. These ideological elements made it easier for them to seek allies abroad: in the Soviet Union, Saudi Arabia or Iran.

The armed confrontation between Israel and these groups has been going on intermittently for about 40 years. Alongside this, there have been a number of peace talks between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organisation, a political organisation with representative functions, mediated mainly by the United States. Despite this, the problem has not yet been resolved.

At the same time, the idea of creating two separate states, Israel and Palestine, is popular among Israelis. In July 2023, 36% of Israelis considered creating two independent states the best solution. This is not a majority, but the option received the most votes.

On the 50th anniversary of the Yom Kippur War, several armed groups led by the Islamic Resistance Movement launched another offensive from Gaza, a Palestinian territory not controlled by Israel. The war crimes committed by the militants will affect the Israeli society's attitude to the ways to end the conflict. But are there any other ways?

Entire libraries of books have been written about the Arab-Israeli confrontation. You will be able to read them after the current stage of the Russian-Ukrainian war is over. But for now, the next chapter in the war for Palestine teaches us only one thing: the world remains a dangerous, unpredictable place, and Ukraine's relative security in it is possible only through hard daily and joint work.