Schools in modern realities. How do Ukrainian children get educated?

The second school year in Ukraine has already begun in the context of Russia's full-scale invasion. Not all schools could launch offline classes due to the security situation in the regions.

Pupils of Kharkiv schools came to metro stations instead of schools. The latter have been equipped with lighting, metal-plastic windows and doors, air recovery systems, noise insulation and toilets.

Some children could not attend school on the first of September because a Russian missile destroyed it. Someone's city is under occupation, and the Russian military is stationed in their school. Someone thousands of kilometres away from their home will try to combine studies abroad and in Ukraine.

The article tells about the work of a school with no physical premises, forced to open in another city because of the Russian occupation, and a school abroad that gives a piece of Ukraine far from home.

Mariupol Lyceum in Kyiv

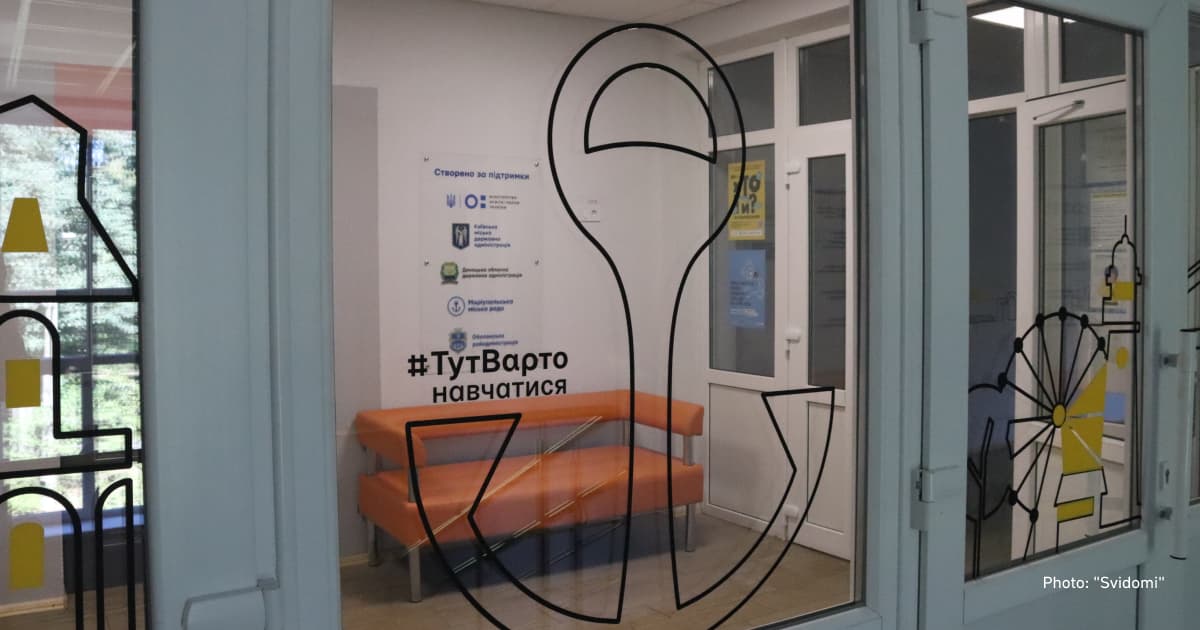

Amidst the noise and laughter of schoolchildren on the playgrounds, I hear the sound of a bell ringing through the open windows of the Mariupol Lyceum in Kyiv. Someone's lesson or break has started. Here, flags of the Donetsk region are flying on the walls, and anchors, a symbol of Mariupol, are depicted on the door. At the entrance, Vice Principal for Educational Work, Iryna Tsynkush greets me with a smile.

Before the full-scale invasion, the lyceum taught Mariupol students. After February 24, 2022, the educational process came to a complete halt due to the Russian invasion. Iryna Tsynkush said that the school was unable to leave. Instead, the staff and students managed to evacuate to the government-controlled areas or abroad.

"When we left, we started collecting information about the whereabouts of teachers and students. We gathered for a pedagogical council in early April, where two-thirds of our staff were present. We decided to stay open," says the Vice Principal for Educational Work.

On 6 April 2022, the school managed to resume remote education.

"At the end of the school year, the Ministry of Education informed us that we could not issue certificates for the ninth and eleventh grades. We had no database because everything was left in Mariupol. The electronic diary and journal were not enough. Then we started redirecting students to other schools, where we agreed they would be issued documents based on their grades during distance learning with us," says Iryna Tsynkush.

On September 8, 2022, the lyceum was informed that it would be provided with physical premises — the second floor of the Special Boarding School No. 4 for blind and visually impaired children. On January 2, 2023, the lyceum started working offline.

Currently, the school enrols about 300 students, with 80 of them attending the physical premises. The lyceum has classes from eighth to eleventh grade, with up to 35 children in some classes. There were about 450 students in Mariupol.

The new lyceum building also houses a boarding school, where 40 children live and study simultaneously. Most are displaced children from Mariupol, Bakhmut, and the Kherson region.

We have a synchronous learning mode for children abroad — they study simultaneously with everyone else offline but via a remote connection. In one of the classes, a maths lesson was just taking place. There were more than ten children in the classroom, but at the same time, there was a broadcast with students from abroad. For such lessons, teachers have an interactive whiteboard where they write, and children can simultaneously see it live and via the broadcast.

In one of the classes, I noticed interesting constructed projects — the Eiffel Tower and a drone. As Iryna Tsynkush explained, the school has STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Mathematics) classrooms. These are lessons that show complex processes using visualisation.

"These are applied skills when children assemble robots and quadcopters from various materials," the woman says.

In preparation for the new school year 2022/2023, the directorate first equipped shelters, especially for children who are permanently at school.

"The previous [school] year [2022/2023] was the most difficult for us. It was the opening of a new school when we had to transfer all the teachers to Kyiv. Some were in Ukraine, and some were abroad. We used to live somewhere for free. Our principal, Andrii Holotiak, gathered the staff in one city, and everyone moved. Now, we are renting apartments in Kyiv on our own. But we are all together, so we continue to work despite all the challenges," says Iryna Tsynkash with a smile.

Cherkaska Lozova, Kharkiv region

A school in the village of Cherkaska Lozova, about 10 kilometres from Kharkiv, continues to operate. On April 24, Russians shelled the Cherkaska Lozova lyceum. Before the full-scale invasion, 270 children studied there. Now, they all lost the opportunity to study offline due to the lack of premises.

The lyceum's principal, Tetiana Korin, meets me in a green dress with a smile to tell me about the school, its students and the current learning environment. She is a teacher of the Ukrainian language and literature and a graduate of the school.

A few metres from the building, the consequences of the Russian shelling are immediately visible — a burnt yellow and orange building with no windows, roof or doors, and in some places, no walls or floor partitions. Offline learning is not possible here, and the building is beyond repair.

The first hit was in March when one window was smashed. Then, in mid-April, another hit started a fire in the library. A few hours after the school caught fire, there was another hit to the gym, where we had piled all the valuable equipment, books and documents. Everything burned down.

"The school was built in 1937. At all holidays and events, we used to say that our school was holy because not a single shell hit it during the Second World War. This war destroyed the school," says the principal.

After February 24, 2022, the lyceum entirely switched to the e-learning format and still continues to this day. Currently, 230 students study here, including 40 abroad. Almost all the staff was also retained, including 22 teachers.

"We completed the entire curriculum for last year online despite all the difficulties. We are proud that the school year is over, and we have four graduates with honours," says Tetiana Korin delightfully.

In 2020, the school underwent extensive renovations, including insulation, new desks and blackboards, and each classroom had a computer and TV. Before 2022, the school received one-seat desks and an interactive whiteboard for primary school children. It was a gift for St. Nicholas Day. However, they did not have time to equip it all because of the start of the full-scale invasion.

Despite the burned-out library, the textbooks were saved because the students had them. Today, schoolchildren exchange books with each other; the older ones pass them on to the younger ones, which is how children preserve a physical part of the school. However, primary school textbooks have been burnt. Parents have to buy books for their children on their own.

The only thing left of the school is the main entrance. There is a painted tree on one of the walls where photos of all the school's graduates used to hang.

"We were so proud of this entrance because our graduate painted it. I would not have taken the photos if I had known this would happen. They would have survived; instead, we took everything to the gym, and it burned down," says the principal.

The building is no longer full of children's laughter or teachers' instructions during lessons. Only the sound of burnt metal inter-floor beams hitting each other in the wind can be heard occasionally.

On the left side of the entrance, there used to be a chemistry classroom, where the test tubes and beakers used during lessons are still in the lockbox — the largest class of 15 children studied here.

On the right side is a former Ukrainian language classroom, a teacher's room and a library. Burnt metal structures from the desks still lie on the floor. A broken window overlooks a playground where two children are playing.

The principal's office used to be on the first floor, and it was equipped for her almost before the Russian invasion. She kept all her documents and valuable books there.

For the new school year — 2023/2024 — a particular curriculum and timetable have been developed for children abroad — 40 pupils. They study simultaneously in foreign educational institutions and Ukraine. Despite the lack of a school building, the school management did host a first-bell celebration near the village council.

Next to the school, there is a surviving modern sports stadium that was built in 2021. People play football here, gather for dance classes and hold celebrations, including the first and last bells for schoolchildren living in the village.

According to the director, a project is already underway to renovate the institution - a four-storey new building with inclusive classrooms, a dining room, a gym, and toilets in one room. Previously, all of these were separate.

"We will implement the plan on the site of the destroyed school after the victory when all the children will be able to return to Ukraine," says Tetiana Korin.

Ukrainian school in Prague, Czech Republic

Today, about 500,000 Ukrainian children live abroad. Many continue their education online in Ukrainian schools, while others join foreign educational institutions. However, in some countries, there is a lack of space in local schools, particularly in the Czech capital, Prague.

Oksana Breslavska has created the Children of Ukraine association and a school for Ukrainians in Prague since the beginning of the full-scale invasion to ensure that children continue their education and do not lack communication with their peers. She has lived in the Czech Republic for 27 years and has never been involved in education.

"I am involved in a completely different field. It was like a cry from the heart to help children. I am a mother, so my parental experience helped me create the school," she says.

At first, after February 24, she helped children forced to go abroad — she organised primary schools and summer camps, hiking in the mountains, visiting museums and zoos.

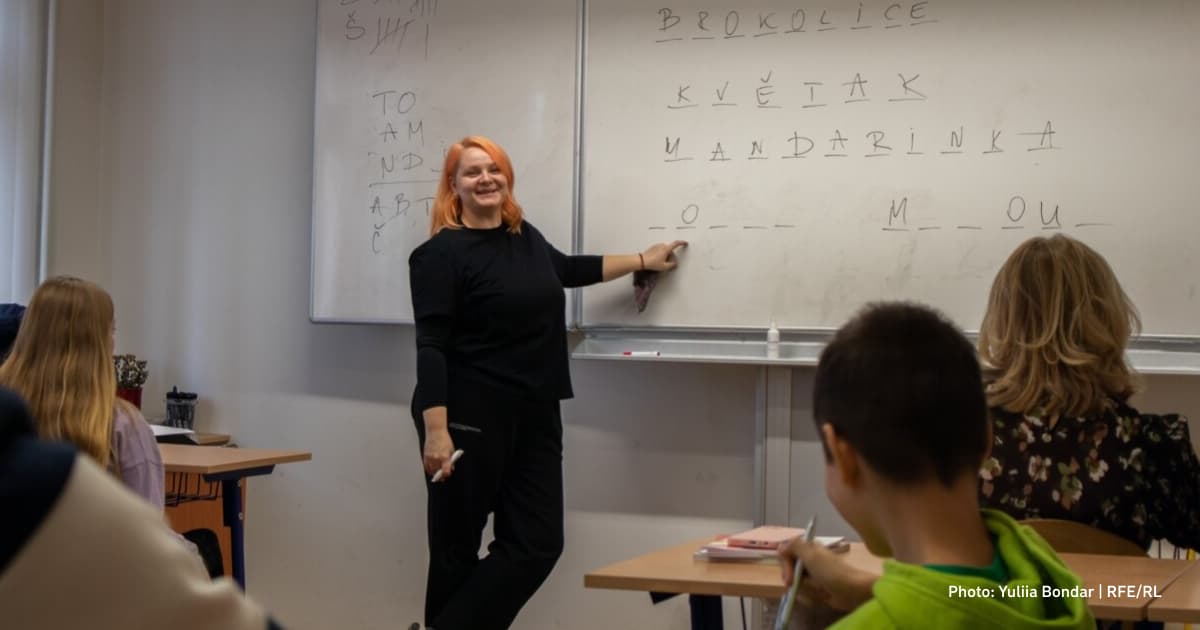

In August 2022, they decided to set up a full-fledged school for children in grades one to eight. Currently, the school operates from the first to the ninth grade, with 99 children from 19 regions of Ukraine. The teaching staff includes 11 teachers from Ukraine. There are two buildings: one for the first, second and third grades and the other for the fourth to ninth grades. The school employs 18 Ukrainian refugee teachers.

"The goal is to create a school so that children do not stay at home alone and do not study only online but are part of the community. We try to make their stay in the Czech Republic the most enjoyable," says the school's founder.

The curriculum at the school fully complies with Ukrainian educational standards but with an in-depth study of Czech and English. Children can also attend various clubs, including computer classes.

The Czech school cannot issue certificates and diplomas to students due to the lack of accreditation. However, the children still attend Ukrainian schools, receiving secondary education certificates.

"Last year, the schoolchildren negotiated individually with teachers in Ukraine to provide each child with a confirmation of their level of knowledge," says Oksana Braslavska.

The move and new living conditions have had a moral impact on the children.

"At the beginning of 2022, patting them on the head was impossible because everyone was stiff and scared. In autumn, there were positive changes. The children made friends and became more relaxed," the woman explains.

Psychologists work with the children. "When asked: "How do you cope with negative emotions?", they [the children] answer that they stay at home alone, scream and cry. When asked: "Why don't you tell your mum?" the children fall into two categories. Those who don't want to upset or hurt their parents with their problems. And those who have a grudge because they were forced to move to a new country and adapt to a new life," says the school's founder.

The school is funded through grants, donations and the founders' and parents' funds. The Czech government refuses to provide funding because the school teaches in Ukrainian.

"We have many children whose parents are at war. One of the reasons we created the school is to help those who are fighting by showing them that their children are safe," says Oksana Braslavska.