Resistance in deportation

The deportation is one of the most dramatic episodes in the history of the Crimean Tatars. But even during the deportation, the Crimeans never stopped dreaming of returning to their homeland.

Yes, at first, the hope was stronger, and some Crimean Tatars did not even build houses in the places of deportation. But as time passed, more and more people realised that the Soviet government would not return the people to Crimea (Qırım).

What happened between 1944 and 1991, when the Crimean Tatars were deported?

The Resistance Movement

Some Crimean Tatars tried to return to the peninsula by writing letters to the Soviet authorities. However, Stalin's system quickly crushed their resistance.

The first initiative groups appeared in the autumn of 1957, and by the mid-1960s, they were active in almost every settlement in Central Asia. One example was the actions of two Crimean Tatar boys, Enver Seferov and Shevket Abdurakhmanov.

"You want our nation to gradually dissolve among other nations and cease to exist as a nation. You will not be able to do that. The time has come to understand this. We demand that you respect our nation and let us return to our homeland."

Crimea is ours, and sooner or later, you will recognise it. Today we have one goal - home or death. And you will soon feel that the responsibility for everything that has happened lies entirely with you.

Despite this, hundreds of Crimean Tatar families continued to leave for Crimea. Still, they were denied documents, work or education.

Attempts by people to return to Crimea en masse and to meet with human rights defenders led to increased repression. Well-known activists and human rights defenders - Mustafa Dzhemiliev, Ilia Habai, Petro Hryhorenko, Reshat Dzhemiliev, Yurii Osmanov, Rolan Kadyiev and many others — have been sentenced to various terms of imprisonment in fabricated criminal cases.

The story of Mustafa Dzhemiliev

Mustafa Dzhemiliev is one of the leaders of the Crimean Tatar national movement. He is also a human rights activist, a member of the dissident movement, a political prisoner and a Hero of Ukraine (the highest national honour that can be awarded to an individual citizen by the President of Ukraine - ed). For his political views, Dzhemiliev was expelled from the university and went through seven court trials. He spent a total of 15 years in prison.

— Weren't you afraid of being killed?

I was more afraid of being disgraced. It was important to maintain a moral victory and not to disappoint my fellow citizens. Of course, everyone is afraid. It is understandable. But my sense of responsibility was stronger than my fear. If you don't do what you have to do, you don't feel fulfilled.

Mustafa Dzhemiliev recalls that at the time, they did not believe they would return to Crimea in their lifetime. They did not even dream that the USSR would collapse. But it turned out that they were able to return to their homeland in their lifetime and witness the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Common history

The topic of the Crimean Tatar resistance movement is interesting in the context of the struggle of Ukrainian figures for independence. In the same years, Viacheslav Chornovil launched the national “sixtiers” (people of the 60s — ed.) movement together with Ivan Svitlychnyi, Ivan Dziuba, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Vasyl Stus, Ihor and Iryna Kalynets, Alla Horska, and others. The movement opposed the totalitarian regime and advocated for the revival of Ukraine, its language, culture, spirituality, and state sovereignty.

Similar methods to achieve their goals. Similar searches in their homes. Similar punishments from the Soviet authorities. Deportation to the most remote corners of the USSR.

The two movements are yet another proof that the history of Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars cannot be considered separately. For it has always been, is, and will be a common history of Ukraine.

Mustafa Dzhemiliev recalls his correspondence with Viacheslav Chornovil when they were both in exile. Chornovil wrote that the Crimean Tatars needed to change their strategy because Ukraine would gain independence. And Crimean Tatars would be more comfortable living in an independent democratic Ukraine than in Russia.

Nadzhiie's family history

Najie Ametova's father joined the national movement, or rather its participants, when he was about 25 years old. At that time, the activists were fighting for the rights of the Crimean Tatar people and, in fact, for the return of the Crimean Tatars to their homeland.

Nadzhiie's grandparents used to tell her father how wonderful Crimea was, how beautiful it was, that it was a paradise on earth. When the Crimean Tatars began to return to Crimea, they would look down the aeroplane ramp and try to see where paradise was, but there was a desert. "But, of course, for my father, it was paradise. We have a very strong attachment to the land; we feel it wherever we are," says Nadzhiie.

Crimean Tatars used to resist nonviolently. In the early 90s, around May 15-16, Crimean Tatars from different parts of Crimea left their homes and marched to Simferopol (Aqmescit) on May 18 to honour the memory of the victims of the deportation of the Crimean Tatar people. And to remind them of themselves, "We are here, give us the right to learn our language, give us the right to move into our homes. Give us the right to be here, Indigenous as we are, a people on our land."

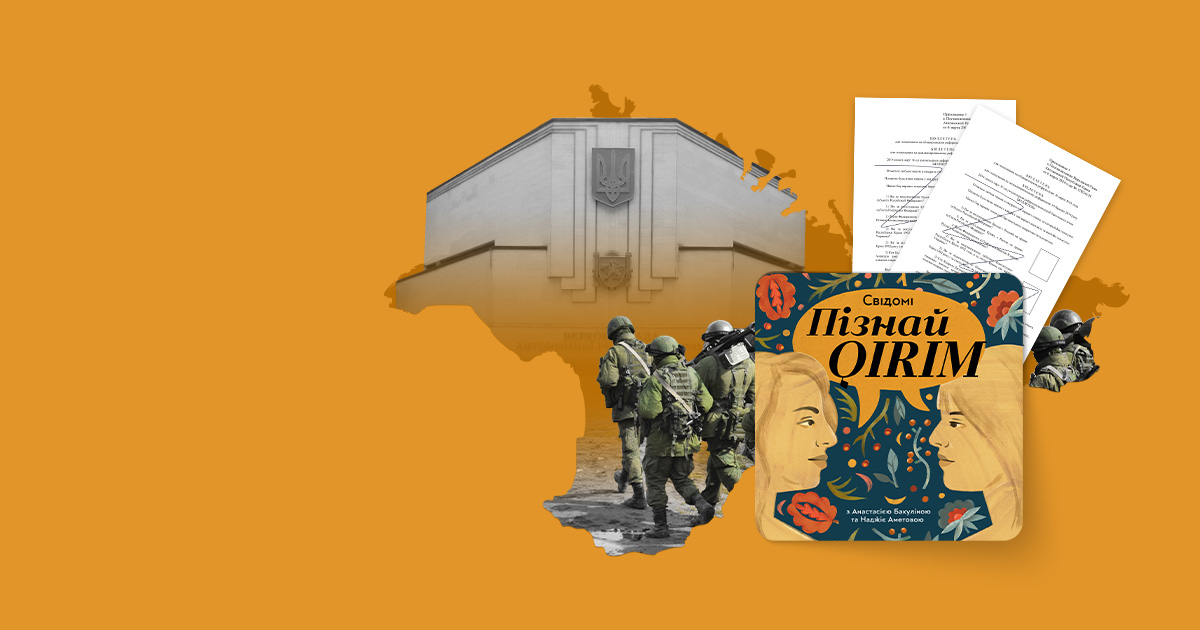

The Crimean resistance movement after 2014

There is definitely a resistance movement in Crimea. In fact, you have to live in the occupied territories to understand these people and the risks they face there.

Crimean Solidarity is also one of the heroes. These people know for sure that even here, near the courthouses, where they go to support political prisoners, they can be arrested, but every time they come, there are more and more of them. And that is also resistance.

The Yellow Ribbon is such an accessible form of resistance to the occupation. It is based on the special desire of people from the occupied territories to find their place in these great historical events, with the clear understanding that if for some reason they cannot leave, they still do not want to lose contact with Ukraine.

In 2022, we saw a profound qualitative and quantitative change. After the occupation of Crimea, the situation for many inhabitants of the peninsula remained unclear for a long time. However, the outbreak of a full-scale war significantly accelerated the processes. And for a large number of Crimeans, the war became a realization that this was a moment that offered more opportunities for de-occupation.

The fact that the Crimean Tatars are united in ideas and values is proved by the fact that the resistance movement was formed long before the deportation in 1944. Now, the resistance movement of the Crimean Tatars continues. It is important to communicate with those who became its leaders while they are still alive, to learn more about the country's history, and not to repeat the mistakes of the past.