On the Turbai villagers who were resettled to the Tavria steppes after the anti-serfdom revolt

The Turbai Uprising was one of the largest anti-serfdom revolts on the Left Bank of Ukraine in the second half of the 18th century.

"Ukrainians have always been distinguished by their high capacity for self-organisation in the conditions of statelessness. Consider the history of our armies, which for a long time defended a stateless nation," says historian Yurii Harmatnyi.

As an example, he cites the opryshky (groups of social brigands active in the Ukrainian regions of the Carpathians from the 16th to the early 19th century — ed.), haidamaks (mainly peasant serfs, craftsmen, and impoverished noblemen in the eastern part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth — ed.), Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) and Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA, a Ukrainian nationalist paramilitary and partisan formation —ed.) rebels who fought under Moscow totalitarianism.

"Turbai self-government has become a vivid testament to the high capacity of Ukrainian society to self-organise. As the Maidans (a wave of street protests in Kyiv’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) sparked by then-President Viktor Yanukovych's sudden decision not to sign the European Union–Ukraine Association Agreement —ed.) have shown, we have retained this ability to this day, despite the genocide orchestrated by the Moscow communists," adds Harmatnyi.

Read more about the events in Turbai, Poltava region, how the villagers ended up in the Kherson region, and what is happening to these settlements in the south of the country in the article by Svidomi.

The uprising in the village of Turbai

According to historian Ihor Koliada, at the beginning of the 18th century, Turbai was considered a free military village and was part of one of the hundreds of the Myrhorod Regiment.

Turbai was founded between 1630 and 1640 in the Poltava region. At that time, the settlement was part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

As a result of the war of liberation in 1648-1654, the Left Bank of Ukraine was freed from Polish serfdom.

But in 1711, the then-hetman of the Zaporizhian Host, Danylo Apostol, removed the Turbai Cossacks from the register and enrolled them as his "subjects." The Cossacks' demonstrations against enslavement were suppressed. Only 76 Turbai residents were returned to the register. After Danylo Apostol's death, Turbai was passed to the hetman's wife Uliana. Later, it was passed to her granddaughter Kateryna Bytiahovska, who sold the village to landowner Fedir Bazylewski.

The Bazylewski family continued to oppress the villagers, robbing them, taking their cattle and cutting down the forest.

In response to the brutal beating of the Cossacks-Roman Kobzar, Nazar Olefir, and others whose families were sent to hard labour in the hamlet of Ocheretuvate-the Turbai villagers turned to the court again. They demanded to be enrolled as Cossacks.

However, in 1788, the Senate recognised the right to Cossack status only for those 76 families that remained in the register.

"Soon, all the villagers gathered in the otaman's yard. They were waiting for the court's decision. At this uneasy time, a community herdsman, Matvii Shapovalenko, rushed from the field and quickly said: "They are taking the herd (taking the villagers' cattle — ed.)!" This was enough to make the hatred for the Bazylewskis, which had been building up in the soul of every Turbai resident for years, explode with great force. The peasants did not ask who it was, but, armed with whatever they could find, they rushed to their herd in the field," wrote Ihor Koliada, PhD in History, Professor at the National Pedagogical Drahomanov University, Kyiv.

The next day, the officials and soldiers were released after taking a written statement from them that all the peasants had voluntarily joined the Cossacks.

On June 8 (19), 1789, the Turbai residents established their self-government according to the Cossack model. Nazar Olefir, Hryhorii Yastrubenko, and Tymofii Dovzhenko were in charge. Matters were resolved at a village meeting, and power was exercised by the otaman, Cossack leader, judge, and record clerk.

In April 1793, Catherine II decided to suppress the uprising by secretly sending military troops to the village. It was decided to resettle the Turbai residents. An infantry battalion with two cannons and 200 Cossacks was sent to the village to suppress the uprising.

"The most active participants in the uprising — Stepan and Leontii Rohachky, Musii and Manoilo Parkhomenko, Pavlo Olyfirenko, Vasyl Nazarenko and Hryhorii Velychko — were sentenced to death, which was later commuted to 100 lashes and life hard labour in Tobolsk (a city in the Tyumen region of Russia — ed.)," Koliada's article reads.

Other peasants were punished with whips and exiled to the steppes of the Tavria and Kherson provinces. The Russian Empire's government changed the village's name to Skorbne. Only in 1919, at a meeting of villagers, was the historical name Turbai returned to the village.

According to various estimates, approximately 100 peasant uprisings were recorded in the Poltava region in the first half of the 19th century as a result of disenfranchisement and increased exploitation.

Where the Turbai residents were resettled

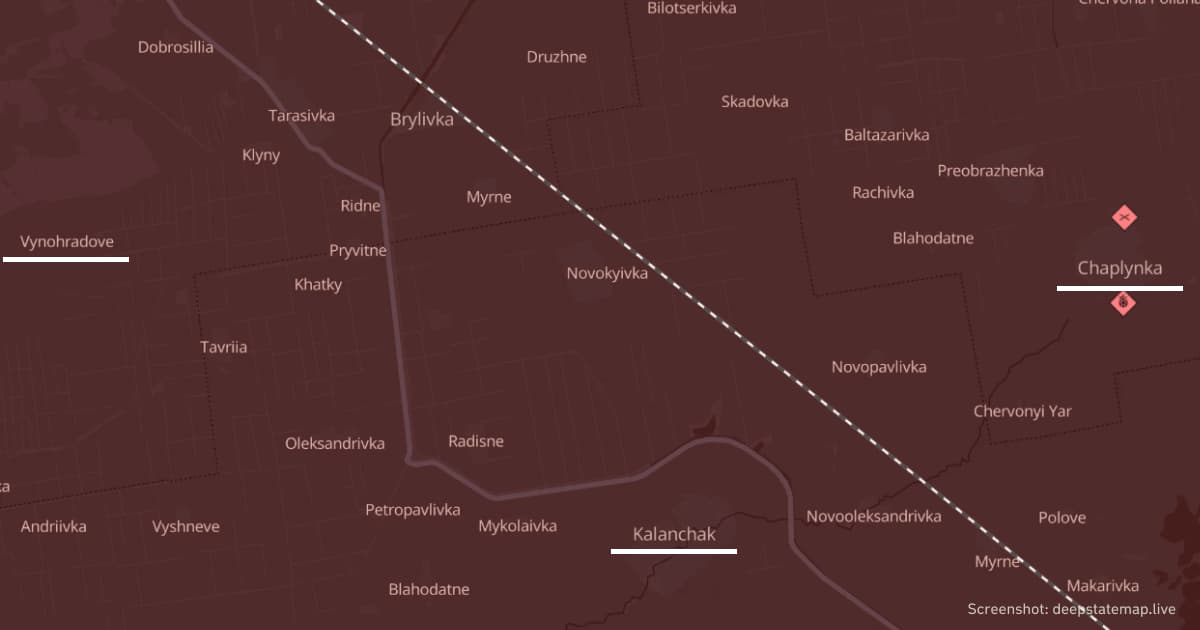

The villages founded by the Turbai villagers belonged to the Tavria province, on the left bank of the Kherson region.

However, very little information about them has survived. "So the records about them should be in the archive in Crimea (Qırım, temporarily occupied by Russians —ed.). They were not in the Kherson archive (even before the looting by the Russians in 2022)," says historian and member of the Ukrainian Heraldic Society Oleksii Patalakh in a comment to Svidomi.

A few references to the resettled Turbai residents were nevertheless found in the public domain.

In 1794, the Chaplynka village was formed on the Chumak's path (the route the salt merchants took across the steppes in the South of Ukraine to sell their precious commodity at vendors’ markets) from Kakhovka to Perekop. Its founders were 25 families of Poltava peasants, driven from their homes for participating in the Turbai Uprising.

The founding of another village in the Kherson region is also associated with the resettlement of Turbai residents. Thus, Chalbasy (later Vynohradove) was formed on the site of a former Tatar settlement. This is described in the work "History of Towns and Villages of the Ukrainian SSR. Kherson Region".

"The displaced people suffered a lot. To punish the disobedient, the authorities banned them from digging wells. Water was only allowed to be taken from the Dnipro River, 50 km away from the village. Therefore, in Chalbasy, a mug of water was valued more than a piece of bread, despite the famine. Water bought from shopkeepers was used to treat guests; according to a local custom born of the horrific reality, a person on his deathbed was to be given clean water for the last time," the document says.

Chalbasivka residents were allowed to dig wells only in the early 19th century.

"At the cost of superhuman efforts, the freedom-loving, strong-minded Turbai villagers and their descendants settled in the wild steppe," historians wrote.

In addition, several hundred Turbayv residents were sent to Biliaiivka and Yasky in the Odesa region.

While researching his ancestry, Oleksandr Zhurenko from Biliaiivka discovered that more Turbai people were coming to the village than Biliaiivka residents had lived there before.

"The only thing we can say is that we are more Turbai than Biliaiivka. There were 300 and 600 came," Zhurenko says.

What is happening now to the settlements founded by Turbai villagers in the Kherson region?

Kalanchak, Chaplynka, and Vynohradove are located on the left bank of the Kherson region. Since February 2022, the settlements have been under Russian occupation.

The Russians continue to exert pressure on the locals facing temporary occupation. Human rights activists and journalists report on the killings, torture and detention of civilians in the territories.

For example, in February 2024, the Russian military abducted and later killed Ukrainian priest Stepan Podolchak in Kalanchak.

In May 2024, representatives of the occupation authorities in Chaplynka founded a Russian military-patriotic organisation called the Yunarmiya (the All-Russian Military Patriotic Social Movement — ed.). During the opening, the Russians forced schoolchildren to swear an oath of allegiance to the Russian Federation and the Yunarmiya Brotherhood.

In addition, in June, the Russians published a list of residential premises that would be "put on the register" if their owners did not provide the illegal authorities with documents confirming their ownership. The list included houses from Chaplynka and Vynohradove, among others.