Güzel Qırım

The story of this family's deportation differs from the others recorded before. It will not contain many details about Crimea (Qırım), descriptions of the smells from favourite places, or Crimean Tatar proverbs. It will not because Russia has committed two crimes in three generations of this family.

This year, Asan Isenadzhyiev, a veteran of the 12th Azov Special Forces Brigade and a paramedic from Azovstal, who managed to survive captivity, torture and the tragedy in Olenivka, shared his story. Due to captivity and torture, Asan lost some of his memories. It is difficult for him to recall the details of his life in Crimea and his stay in Mariupol.

Güzel Qırım is the name of a Crimean Tatar song that Asan's family taught him and the one he sang while in captivity. The title translates as "My Beautiful Crimea".

Every year on May 18, Ukraine commemorates the victims of the deportation of the Crimean Tatar people. According to the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, in 1944, the Soviet authorities deported about 200,000 Crimean Tatars from Crimea, of whom more than 46% died of starvation and unsanitary conditions during transportation and at deportation sites in Uzbekistan, Qazaqstan, Tajikistan and other regions of the USSR.

Read about two crimes of Russia in the family of Asan Isenadzhyiev in the article by Svidomi.

Captivity

My grandfather fought near Cologne, Germany, during the Second World War and was wounded in the left eye, losing it. He fled back to the front when he was sent to a hospital. A few days later, my grandfather was declared a traitor and was deported.

My grandmother was still a child when the deportation began. She was no more than five years old. They were taken to the railroad cars, and she remembers very clearly that small children were taken separately. When one child fell down the ladder and started running away, dogs were set loose on her, and she was mauled.

Crimean Tatars were transported in freight cars to Uzbekistan for three days without food or water. Then, a lot of people died from the heat, and several were beaten to death. They were buried when they stopped to change the wagons. My grandmother said that during the May heat wave, they travelled with the dead bodies for a very long time because there were no stops.

They were brought to Uzbekistan, where the locals met them with hostility. They were treated with disdain, so they constantly had to fight for their right to exist. For a long time, there was a ban on education, so from childhood, my grandmother had to work gathering flax plants. They had a "point man" and could not go more than five kilometres away, if memory serves. It was drudgery. They were not trusted with any other work, not because the Uzbeks were against it, but because it was forbidden. At that time, the passport still had a fifth point on "nationality" (nationality was the fifth entry in these documents, following surname, name, patronymic and date and place of birth; it has been known as the ‘fifth point’ — Piata grafa — ed.). And if it said Crimean Tatar, that was it — the door was closed.

There was no work, and we had to earn a living to feed our children. My grandmother told me that the first petals of tobacco were considered the most expensive. They used to collect them and resell them to buy bread. They also said that there was a flower that blooms only two weeks a year. And the pollen of this flower is also very expensive, more expensive than gold. I can't remember the name, but it is used as seasoning. And everyone who picked tobacco would go to collect this pollen. Of course, no one gave all the pollen. They gave away about 90% of it and kept 10% to get more food and clothes for the children. That was the life in captivity.

Güzel Qırım

In the early 90s, my family returned to Crimea, where my parents met and I was born. Families built their houses from scratch because other people lived in their homes.

When I was growing up, I was told about deportation, avoiding details. Unfortunately, my family tried to pass on the traditions to me, but I wasn't that interested then. I remember they talked about wedding customs, the essence of which I don't remember much. They also passed on the language: I was taught to speak Crimean Tatar and sing folk songs. However, I am not very fluent in Crimean Tatar at the moment. Even when recording my latest address to Erdogan, I had to learn it for about a week.

My grandfather taught me math and developed my mathematical thinking. Throughout my childhood, he gave me math problems because he was an artilleryman, and calculations were very close to him. I would get 5 kopecks for solving the problem correctly.

My family instilled russophobia in me. We were told not to trust Russia. My grandmother always spit at the TV whenever she saw something about Victory Day, exaggerated "victorious" hysteria in Moscow, etc. As the youngest in the family, I always had a rag to wipe the TV. My grandmother would openly spit on the TV, and I would wipe it off.

As a child, I often went to Simferopol (Aqmescit), where I lived on the outskirts. There is a forest nearby, a river, a poplar tree, and a cow named Maia. I don't know why, but I liked wrangling up the cow and running to the river with my dog Zhuzhyk. I would throw him a stick, and he would bring it back. I also liked going to Bakhchisarai (Bağçasaray). We often went to the mountain city fortress of Chufut-Kale (Çufut Qale) with the class. There is lovely vegetation, dense forest, clean air and a beautiful view.

Growing up

I was 17 years old when helicopters started flying and Russian "little green men" (Russian soldiers without insignia on their green uniforms that seized control of Crimea in 2014 were dubbed the "little green men") appeared in Crimea. At first, my friends and I found like-minded people. Back then, we had scoots but no money for fuel, so together, we looked for Zhiguli decorated with St. George's ribbons, drained them of gasoline to drive around, and looked for collaborators. We passed information to the police and the Security Service because we believed that most of them would do something. We all believed in that.

During the rally on February 26, we walked around and met people with red ribbons, Aksyonov's people (Russian-appointed head of Crimea Sergey Aksyonov, who founded volunteer battalions on the peninsula). My parents did not want to let me go, but I went anyway. I walked into a crowd where everyone was pushing each other in the forward/backward direction. I started pushing them, too. I didn't understand how I ended up in the front row. You can hardly raise your hand because you are pushed back and forth. Then, the bottles and cobblestones came flying. One cobblestone hit the guy next to me in the head.

A pro-Russian activist started pushing me. I tried to hit him on the forehead. He was outraged by this. He started hitting me because his hand was higher. That's how he knocked me out. I came to my senses behind the building when they were carrying me. Later, we went away.

Next came the Belbek airport defence. My friends and I decided to go there. The guys were in a complete blockade. We brought them water, cigarettes, and waffles. Since we were not allowed to buy cigarettes in cartons because we were underage, we found a man and a driver. We bought a few cartons, contacted the guys, and found a place to drive up to. We ran there like a raiding party, handed them the cigarettes and left.

Then we decided to go to Sevastopol (Aqyar) for a cup of coffee. But there were "striped weirdos" with ribbons and St. George's armbands. A riot broke out. Guys from one Crimean Tatar organisation brought me to my senses. I regained consciousness in Bakhchisarai.

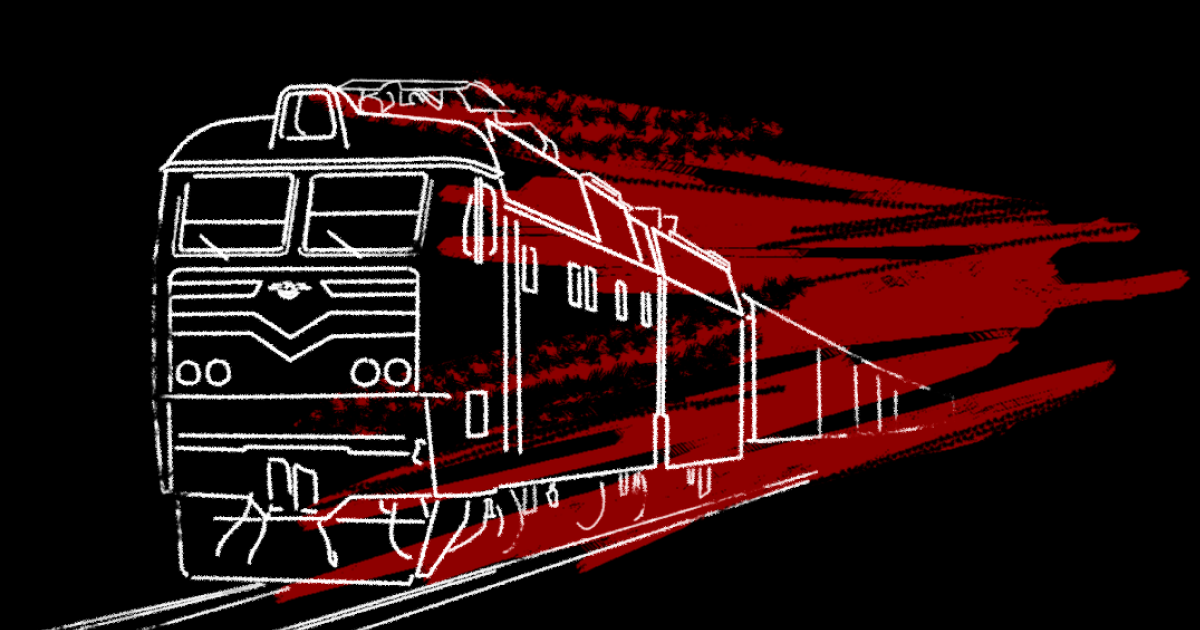

There were different rallies then, but my classmate turned me in. I was in close contact with a girl he liked, and he decided to "remove" a competitor. I told her everything. Then she called and told me I had been handed over to the Federal Security Service. So I took the Simferopol-Kovel train and left Crimea. I realised that I was going for a long time.

I have never been back to Crimea since then.

96 days

I wanted to become a programmer, but my family decided I should become a doctor. I couldn't enter medical school because my family didn't have the money to pay for my education, so I enrolled as a paramedic. After that, I joined the army, which I had been dreaming about since the beginning of the Russian-Ukrainian war. It was an obvious decision for me: I wanted to be useful to my country, which was invaded. After all, I am first and foremost a Ukrainian and then a Crimean Tatar.

I served at Chonhar initially, and in 2018, I transferred to Azov. I knew there would be an offensive long before February. However, I thought it would happen on the 22nd. When it didn't, I planned a vacation. On February 23, we were put on full alert. Then there was Azovstal, where I helped the wounded despite the lack of medicine. We were surrounded, and I realised that the only way we could get out was as prisoners.

And so it happened. We were captured on May 18. On the way to Olenivka, I was thinking about the situation's symbolism. We were promised that everything would be under control in captivity—although, of course, captivity is captivity. But I didn't expect things to get so big.

In Olenivka, I was "lucky" to get to barracks 200, where we were blown up. (On the night of July 29, the Russians carried out a terrorist attack in Olenivka, where the defenders of Mariupol were held. The explosion killed 53 people and injured 120). "I don't understand how I survived. I was thrown by the blast wave. My battle buddy was lying next to me with a huge hole in his head. Shrapnel hit my shoulders, leg and ribs. After the attack, we, 36 wounded, were placed in a punishment cell meant for six people. And the torture began. It lasted for 96 days. They taped my eyes shut and tied my hands with the tape, too. I was subjected to all kinds of torture: they beat me with their hands, kicked me, and gave me electric shocks. Once, they smashed a chair against me. We were not allowed to go to bed during the day and slept with the lights on.

During my captivity, I often thought about my family's fate and the hardships we faced. There, I hummed a song my grandmother had taught me — Güzel Qırım.

I was preparing myself for the worst. So, at some point, I started to imagine that my whole family was dead and I was burying them. After that, it wasn't so scary anymore.

We were exchanged on December 31, 2022, and I returned to Ukraine.

***

I believe in miracles, but I don't believe in happy endings. I hope that at least my children will visit Crimea. If I do manage to return, I will probably go to Demerdzhi-Yayla (Demirci yayla) or the village of Nyzhnia Kutuzovka. I used to go there with my classmates. There are vineyards, a forest, a mountain, and a water reservoir. One can see the sea. Birds are singing. There are also storks. And horses are grazing.