From rallies for European values to protests against Russian aggression — why people came to Euromaidan in the south of Ukraine

Protests during the Revolution of Dignity took place in all the country's cities: Lviv, Ternopil, Cherkasy, Dnipro, Donetsk, Kharkiv, and Kyiv. They also took place in cities in the south of Ukraine, such as Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, Mykolaiv, and Odesa.

In these cities, however, the protests in solidarity with the country's European course and against the beating of students in Kyiv on the night of 30 November quickly turned into something else. People came out not only for European integration but also for the integrity of Ukraine as a state, for their belonging to it, and then against Russian aggression in Crimea (Qırım) as well as in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, and against separatism.

Svidomi spoke to protesters in Odesa and Mykolaiv about the Revolution of Dignity in the southern cities.

"We want an independent, sovereign Ukraine. Away from Moscow" - what the Odesa protests were about

The protests in Odesa began as a response to the events in Kyiv. On the evening of November 21, 2013, when students protested against the suspension of the European Union–Ukraine Association Agreement by the then government of Viktor Yanukovych (the fourth president of Ukraine, convicted of treason — ed.), Odesa also came out in protest. However, for a city of a million people, there were very few people there. They were united by their long history as pro-Ukrainian activists.

Nataliia Mykhailenko, a Euromaidan activist, organiser of the embroidered shirt march in Odesa, and former director of the Odesa Regional Centre for Patriotic Education and Leisure of Children and Youth, talks about the beginning of Euromaidan in Odesa.

"We started gathering near Duke (the monument to Duke de Richelieu on Prymorskyi Boulevard - ed.) They were mostly pro-Ukrainian activists - Vitalii Ustymenko (one of the co-founders of Automaidan, a soldier of the Armed Forces of Ukraine — ed.), Oleksii Chornyi (head of the children's educational NGO Expedition, a serviceman of the Armed Forces of Ukraine - ed.), Oleksandr Ostapenko (associate professor at Odesa Polytechnic University - ed.). And the first thing that distinguished our Maidan from Kyiv's was that we immediately set up tents," Nataliia says about the participants of the Odesa Euromaidan and its main activities.

About three hundred people came to the first protest. Nataliia Mykhailenko says that at first, the actions took place at a certain time, usually at 6 p.m. every day. This gave the protests a regularity, and people knew when to come out. But on the night of November 24-25, the police dispersed the demonstrators and destroyed the tent city. Thousands of Odesa residents continued to protest later, in January 2014.

The beating of Euromaidan protesters in Odesa went unnoticed in Kyiv and other cities in western and central Ukraine. Here the then government tested the method of dispersing protesters, a technique it would use six days later in Kyiv on November 30, 2013.

Odesa had a strong reaction to the beating of protesters in Kyiv on the morning of November 30 and a rally gathered around Duke on the Boulevard in the afternoon. Since then, the protests for association with the European Union have turned into a full-blown Revolution of Dignity. This was mainly because those involved in the protests had different views from the main activists of the Odesa Euromaidan.

"Not all my friends supported the Maidan at first. They said they didn't want Europe, they wanted an independent Ukraine, away from Moscow but separate, so they were against it. And I told them: 'I'm sorry, but now the reality is that we have to choose between the Customs Union (an economic union of Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Armenia — ed.), a horror like the Soviet Union, or the European Union. But the beating of the students changed everything," says Nataliia Mykhailenko, describing the mood of the protesters in Odesa.

Moreover, the events in Odesa only gained momentum as part of the revolution. Nataliia Mykhailenko says that in January, activists blocked the bases of the Internal Troops and Berkut (a former special unit of the Ukrainian Interior Ministry — ed.) and were joined by fans of the local football club Chornomorets.

Football fans played an important role in the Revolution of Dignity in general, and perhaps the most important in the southern cities. It was the ultras who protested against separatism and Russia's annexation of Crimea (Qırım), forming self-defence groups against the police and 'anti-Maidan' protesters.

The ‘anti-Maidan’ movement was formed by opponents of Euromaidan in many Ukrainian cities. They initially supported the anti-European movement and Viktor Yanukovych. Then the movement grew into a pro-Russian one.

On January 22, 2014, on the Unity of Ukraine Day (Den Sobornosti Ukraiiny — ed.), one of the largest rallies in support of Euromaidan took place in Odesa. Nataliia Mykhailenko, one of the organisers of the march on the Potemkin Stairs, says that people came out to protest in Odesa after the news of the deaths of Serhii Nigoyan, Yurii Verbytskyi and Mykhailo Zhyznevskyi in Kyiv ( Serhii Nigoyan and Mykhailo Zhyznevskyi were shot dead by Berkut security forces during riots on Hrushevskyi Street. Yurii Verbytskyi's dead body was found on the city outskirts after he was kidnapped the day before — ed.).

"The rally was supposed to be apolitical. We wanted to form a big blue and yellow chain. But people came en masse in the cold and wind. They chanted 'Yanukovych out', 'East and West together' and other slogans. Then I realised that we would definitely win," she says of that action.

After Viktor Yanukovych fled to Russia in February 2014, in the spring, Odesa residents took part in protests against the annexation of Crimea and the war in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, which Russia launched.

"In February, there was no feeling of joy because we received news from Crimea. Berkut fled to Crimea too. It was hard," says Nataliia about the events of late February, when the Revolution of Dignity ended in Kyiv.

In Odesa, Euromaidan has another definite end date — May 2, 2014. A fire in the Trade Union Building killed 47 people, and four of the victims are still missing. The investigation is still ongoing.

On that day, ultras from Odesa's Chornomorets and Kharkiv's Metalist football clubs planned a pro-unity march from Derybasivska Street to the Chornomorets stadium. Kulykove Pole, where the Trade Union Building is located and which was the site of the anti-Maidan tent city in 2014, is quite far from the planned location of the march.

On May 2, the 'anti-Maidan' demonstrators decided to "prevent" the ultras' march and moved from the camp to the city centre. There, at the corner of Katerynynska and Derybasivska streets, two groups of demonstrators clashed after 3 p.m. Protesters from both sides then attacked each other on Hretska Square and Vice-Admiral Zhukov Lane. At the corner of the lane and Derybasivska Street, a pro-Russian anti-Maidan participant, Vitalii Budyko, shot dead Euromaidan activist Ihor Ivanov with an assault rifle.

This moment became decisive in the clash. After Ivanov's murder, the clashes escalated into a confrontation between the groups, and in the evening, the Chornomorets and Metalist ultras and Euromaidan protesters managed to push the anti-Maidan protesters out of the city centre and back to Kulykove Pole. 'Anti-Maidan' protesters occupied the Trade Union Building and decided to use it to defend themselves against pro-Ukrainian activists.

Both sides used flammable bottles, or so-called Molotov cocktails, to attack the other side. As the investigation is still ongoing, it is not possible to establish what caused such a massive fire in the Trade Union Building. According to preliminary data from the State Emergency Service in the Odesa region, 'anti-Maidan' protesters threw Molotov cocktails from the upper floors downstairs, which could have caused the fire.

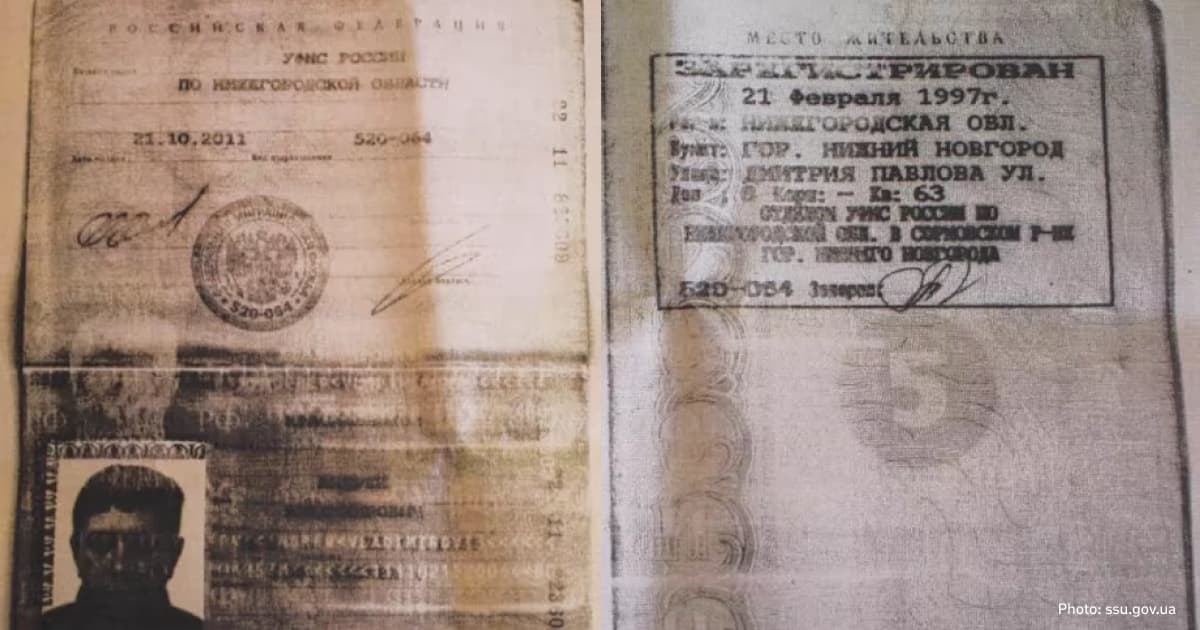

The Security Service of Ukraine, in turn, arrested three Russian citizens on May 3, 2014. They were accused of provocations that led to "clashes and mass casualties on May 2 in Odesa". One of them, Yevgeny Mefyodov, was exchanged in 2019. At that time, Ukraine returned from captivity the sailors captured by Russians in the Sea of Azov in 2018.

The second of May in Odesa had a strong impact on the citizens, says Nataliia Mikhailenko.

"Russian propaganda flourished here. They vividly spread the topic of 'the Odesa Khatyn massacre' (the massacre of civilians in the village of Khatyn, now in Belarus, by the Schutzmannschaft Battalion 118 in March 1943 by arson and shooting — ed.). Even my friends accused pro-Ukrainian activists of "killing poor people". Excuse me, these are not poor people. These people brought the war to Ukraine," she says of the mood among Odesa residents after the events of May 2.

Despite this, Nataliia says that the city has resisted. The main thing now is to collect activists' experiences to understand all the reasons for the Revolution of Dignity in Odesa. Even the events of May 2 are not well talked about in the city because of the investigative procedures. Russia uses this for its narratives.

"I made a powerpoint presentation and went to schools with it. I told the cadets of the University of Internal Affairs about Maidan. Young people need to see a real person who participated in those events. This breaks down the narrative that "they were there for money" and that on May 2 in Odesa, Euromaidan activists burned people more than anything else. I also hope that the Euromaidan cases will be investigated so that everyone knows exactly what happened," Nataliia says in her reflection on the events of the Revolution of Dignity.

"Thousands of people joined in February" — on the protests in Mykolaiv

"Mykolaiv supports the EU" — this was the slogan under which people came out to support Euromaidan on the evening of November 21, 2013. A day later, the police dispersed the rally. The district court in Mykolaiv banned mass rallies in the city until January 7, 2014, due to "a potential threat to participants of peaceful assemblies in the event of possible clashes between representatives of different political forces".

This is not the only example in Mykolaiv. Courts banned rallies all over Ukraine, in Odesa, Kharkiv, Chernihiv and Lviv. In Kyiv, the District Administrative Court of Kyiv banned the erection of tents, including portable ones.

The protesters of Mykolaiv's Euromaidan immediately appealed the decision to ban mass gatherings. They argued that the threat to the participants of the assembly came from the police, not from various representatives of political forces.

Despite the court's decision, people did not wait and continued to protest in Mykolaiv. After the police dispersed the protesters, about 30 people took to the square, journalists of the local newspaper Nikvesti reported for Radio Liberty.

Kateryna Romanova, deputy director general for research at the Museum of the Revolution of Dignity, said that people in southern cities responded to the events in Kyiv rather than advocating certain ideas.

"Initially, very few people came out in Mykolaiv during the first days, dozens of them. Then hundreds. And in February, thousands of people started to join in. When people saw how Yanukovych lived there in Mezhyhiria, how the Party of Regions members lived in general, they had some kind of epiphany that they had been deceived, taken advantage of, so people became more supportive of the pro-Ukrainian movement," she explains the change in mood among the Mykolaiv residents.

The 'anti-Maidan' movement appeared in Mykolaiv almost simultaneously with Euromaidan. They protested near the building of the regional state administration. One of the leaders of the movement was Yurii Barabashov, a local worker in the city's municipal services. Another organiser of the protests was Dmytro Nikonov, a former deputy of the Mykolaiv City Council from Nataliia Vitrenko's Progressive Socialist Party of Ukraine (banned in 2022 by the Supreme Court for its members' treason — ed.) These people opposed the ideas of Euromaidan and campaigned for Ukraine's pro-Russian course.

Kateryna Romanova says it is impossible to say how many ideological participants there were in the 'anti-Maidan' protests in Mykolaiv or how many people came out for money.

"There were people who had a certain dual or openly Russian identity in the southern regions. They could have supported 'anti-Maidan'. But it is impossible to say for sure because the Euromaidan cases are still pending in the courts. We need to look at the available evidence, and exactly how many people took part in the Euromaidan protests, and how these protests ended in these cities," she explains.

Svidomi has already told about the trial of the cases of Euromaidan protesters being shot.

In March 2014, after Russia annexed Crimea, 'anti-Maidan' protests in Mykolaiv intensified. Dmytro Nikonov declared himself the 'people's mayor' and called for a 'federal system' in Ukraine and for Mykolaiv to 'secede' from the country.

The Revolution of Dignity in Mykolaiv ended on April 7, 2014. On that day, Euromaidan protesters dispersed the tent camp in the park near the monument to the paratroopers.

"The 'anti-Maidan' protesters, who advocated the separatism of Mykolaiv and its 'accession' to Russia, tried to seize the building of the regional military administration. The police then surrounded the building and kept it from being overrun by pro-Russian 'protesters'. But the police did not make any arrests.

Euromaidan protesters, led by activist Oleksandr Yantsen and ordinary city residents, gathered near the city hall and went to the regional council. There, they managed to push the 'anti-Maidan' protesters back to the park and demanded that they dismantle their tent camp. After the 'anti-Maidan' protesters refused, the residents of Mykolaiv did it themselves. At 11 p.m. on April 7, the tent camp was dismantled.

"These are tragic events," says Kateryna Romanova, "but in Mykolaiv, they were the result of Euromaidan. In this way, Mykolaiv residents eliminated the threat to the city from pro-Russian protesters and Russia as a whole."

Oleksandr Yantsen died in the first days of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Dmytro Nikonov was arrested by the Security Service of Ukraine in 2014 for encroachment on the territorial integrity of Ukraine.

Yurii Barabashov fled to the temporarily occupied Luhansk after the dispersal of 'anti-Maidan' in Mykolaiv. There he became one of the 'militiamen' of the so-called Luhansk People's Republic. After Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, he collaborated with Russian troops and temporarily served as the governor of the occupied Snihurivka in the Mykolaiv region. After the liberation of the right-bank part of the Kherson region in November 2022, he fled back to Russia. The Security Service of Ukraine served him with a notice of suspicion of collaboration.

How protests in southern cities differ from those in Kyiv

Kateryna Romanova, Deputy Director General for Research at the Museum of the Revolution of Dignity, says Euromaidan as a phenomenon in the country's regions has been rather poorly researched.

"This is a difficult topic because the Kyiv Maidan needs to be researched and explored. It turns out that when the hybrid aggression, the Anti-Terrorist Operation, and the Joint Forces Operation began, it all diverted the attention of researchers to a certain extent. We still needed time to comprehend the events of the Maidan, and then the war broke out. Kyiv's Maidan itself still needs to be studied more deeply in terms of self-organisation and connections," she says about the study of the Revolution of Dignity as a phenomenon.

The researcher says that the Museum of the Revolution of Dignity is accumulating material about the protests in Kyiv and the regions rather than analysing it. Ukrainian historians have a lot of problems with this. Some activists are in the army, so they cannot testify because one interview is not enough. Clarification and repetition are necessary processes for collecting evidence and testimonies.

Identifying common features is necessary to understand the differences between the Euromaidan protests in the southern cities. Kateryna Romanova says that initially, people rallied against the refusal to sign the association agreement with the European Union.

"In Odesa, Mykolaiv, and Kherson, this was the impetus for the protests. But there was an understanding that Ukraine under Yanukovych was falling into the abyss. There was complete chaos in the legal system, there was the actual imposition of these Russian narratives, and people understood that it was either Europe or Russia. All the participants of those Maidans who came out were aware of this," the researcher says about the main motives of the Revolution of Dignity protesters in the regions.

However, the anti-Russian protests in the southern regions were stronger than anywhere else because the Russians were directly trying to undermine the situation in these cities. Russians came to the 'anti-Maidan' protests in Kherson, Mykolaiv and Odesa. According to Kateryna Romanova, activists of the Revolution of Dignity in Kherson told "about buses with the number plates of Belgorod and Rostov, which Russians took to the city".

In Kherson, the Euromaidan self-defence patrolled the city in the spring to identify separatists and Russians after the occupation of Crimea in March 2014. The arrival of Ukrainian troops in the Kherson region to defend the southern regions from the Russian army in Crimea somewhat calmed the situation in Kherson, the researcher confirms.

While the Revolution of Dignity ended in Kyiv on February 22, 2014, protests in the southern cities only grew. In April, pro-Ukrainian protesters dispersed the 'anti-Maidan' protesters in Mykolaiv.

"In February 2014, protesters began to take control of the buildings of regional state administrations in their cities. The situation was the most peaceful in Zaporizhzhia, while in Odesa, it was the opposite. Although the events of May 2 in Odesa were a shock for the city, they forced Odesa residents to answer the question, "Who are we?" says Kateryna Romanova about the spring rallies in southern cities in 2014.

This was the main difference between the protests in the southern regions of Ukraine and those in the central and western regions. People in the southern cities were quickly defining their own identity or had to express it through their active work.

But this was driven by Russia's war against Ukraine, not the initial Euromaidan protests. In a 2018 survey for the Museum of the Revolution of Dignity, more than half of respondents in the southern regions said that the Revolution of Dignity was a positive phenomenon and they did not regret taking part in it.

"Ukraine was united not by the European values of the European Union but by a threat. Because war is always a threat. Ukrainians have finally felt like citizens of Ukraine, and it is the fact that they live in Ukraine on this land that makes them feel proud," sums up Kateryna Romanova, the main consequence of the Revolution of Dignity in the southern cities.