Flee the country with camouflage nets and thermal imaging cameras: how Ukrainian men avoid mobilization

"Your passport data will be entered into the State Border Guard Service database for departure [allegedly] before February 24, 2022. Before you leave, I will put you in touch with the driver, and we will call to agree on the exact time and place," this is how the dialogue between those who avoid military service and those who help them begins.

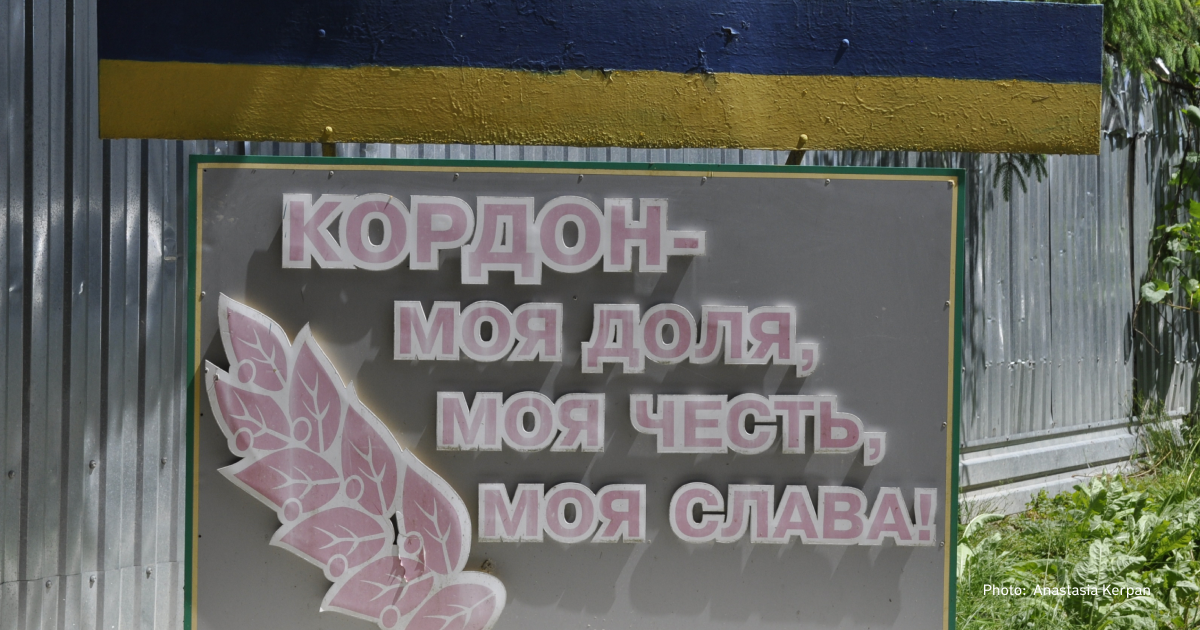

Svidomi went to Ukraine's borders with Slovakia and Hungary to find out how Ukrainians are fleeing abroad illegally.

Read the article to learn how people make money from draft dodgers, how it usually ends, and why the number of Ukrainian men trying to cross the border is growing.

How does it all begin?

Following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, President Zelenskyy declared martial law and general mobilisation in Ukraine. Since then, Ukrainian men between 18 and 60 have been banned from travelling abroad.

The Ukrainian law provides for some exceptions. For example, men who are medically unfit for military service, those accompanying a disabled person or a sick relative, single parents, etc., are exempted from military service and thus may cross the border.

On May 18, 2024, the Ukrainian parliament passed a draft law on mobilisation, which requires men liable for military service to update their military registration. This has led to an increase in the number of men trying to cross the border illegally to avoid conscription.

Routes, instructions and advice on how to cross the border illegally are publicly available. Many men are happy to share their experiences of being 'rescued' via TikTok and YouTube. There are chats on Telegram for shared discussions.

Some have separate discussion threads on what to take, news, finding a partner, legal support, and some kind of club for those who escaped. The channels may have different names and curators, but their aim is the same: to inform those who are planning to cross the border illegally.

Artem Titov, deputy head of the Onokivtsi Border Guard Inspectorate, says in a comment to Svidomi that blocking such channels is pointless because the next day, they can create new ones with identical content and the same people.

If you ignore the context, you might think you're in a chat about sports tourism. Everyone advises which is better: a tent or a hammock, which shoes are more comfortable in the current weather, and how to fit everything into a backpack.

Just practice how you'll set up and leave in the rain. If your poncho serves the roof of your tent, you need to pack and unpack accurately and quickly, like a biorobot,

advises a user called Serhii in one of these chats.

The story of someone who made it

22-year-old Oleh (name changed at the man's request — ed.) crossed the border illegally in April 2022. He planned to leave officially, but when he reached the border, Ukrainian male students were already banned from leaving the country.

He collected all the documents to see if he could leave officially in another way.

"I also received an invitation from a foreign university cooperating with my Ukrainian university to continue my academic year abroad. But that was no reason to cross the border," Oleh tells Svidomi.

After three unsuccessful attempts to cross the border legally, Oleg decided he had no choice.

In my opinion, Ukraine has decided to divide Ukrainian students. For some reason, those who studied in Ukraine had fewer rights than those who left the country after school,

he says.

Oleh found people who offered him a way to escape for five thousand dollars. The guy was sure they would take him to the checkpoint, 'by arrangement,' take him across the border, and stamp his passport upon his exit. It cost him five thousand dollars.

"We were told that it would cost five thousand dollars. We should bring along the money and not take anything else. I took a small bag and cash,’ Oleh says.

He was picked up in Chernivtsi and told to lie in the car so no one would see him. When the car got closer to the border, they had to wait until dark.

The driver said: 'I'm going to open the door quickly, and you should run right after those two guys'. And that's exactly what we did. We ran for about two hundred metres and stopped to catch our breath. I had already realised that the plan was not what I had been told. I was actually running through the woods. And that not everything was as easy as it seemed,

he recalled that day.

Oleh adds that he was unprepared, having been told a different story.

‘If I had been told all the crossing details, I might have considered it too risky,’ the guy says. However, by that time, he had already made up his mind to leave Ukraine.

"We walked through the forest for several hours. Then, the two guys I ran after told me to go on alone. There was a fence with barbed wire, and they opened it so that I could crawl through the bushes on my own and then walk across the plain to the nearest village," the 22-year-old Ukrainian describes.

He crossed the Romanian border and went straight to the Romanian police to obtain temporary protection.

"From that moment on, my official stay in the EU began," Oleh concludes.

The Romanian police asked him how he had crossed the border. But they were more interested in whether Romanian citizens had helped him than in what was happening in Ukraine.

While an independent attempt to cross the border is subject to administrative liability, a planned illegal crossing can result in three to nine years in prison for the organisers.

Organised illegal crossings abroad

On May 22, 2024, five people from the Kharkiv and Zaporizhzhia regions were detained at a site controlled by the ChopBorder Guard Detachment in the west of Ukraine. According to the investigation, the group had two coordinators: one based in Hungary and the other in Kharkiv, east of Ukraine.

"The man who coordinated all the process charged each of the men $14,000. Together with the organiser abroad, they found a local accomplice to act as a taxi driver and pick up the men from the station. In return, he was promised 10,000 hryvnias (half the average wage in Ukraine — ed.). Probably, the man was not told any details," Oleksandr Kovalchuk, deputy head of the Operational Search Department of the 94th Chop Border Guard Detachment, told Svidomi.

The Border Guard says that because of the employment problem in the border area, local people often look for any kind of income and agree to so-called 'fast buck' deals. These people are rarely aware of possible criminal or administrative liability.

According to Oleksandr, the most common scheme for illegal border crossing involves taking a person to a mountainous area, bypassing checkpoints, and then being met by a so-called guide, usually a local, who takes the offender closer to the border.

They can just take you up, point you in the direction and say: '300-500 metres and you're in Hungary'. They can also give you pliers or flashlights,

the deputy head of the Operational Search Department adds.

Once, Kovalchuk says, someone tried to use an ambulance to cross the border illegally in the area controlled by his detachment.

In Uzhhorod, an ambulance crew picked up the fugitives and drove to the border with their warning lights on.

No one expected there might be fugitives in the ambulance.

“The ambulance was not stopped at the checkpoints before the border because the warning lights were on. We stopped the car in a wooded area before the final destination,” the border guard said.

The border guard adds that it is difficult to talk about the statistics of organised border crossings in terms of numbers. The most significant difficulty, he says, is the qualification of the crime: whether it was an organised crossing or an independent one.

"Article 332 [of the Criminal Code of Ukraine] refers to providing advice, guidance, means [or removing obstacles]. Providing the same advice or instructions via a telegram channel is also a qualifying feature of Article 332. But these are often people who cannot be identified. They use anonymous Telegram accounts from abroad," says the border guard.

It is difficult to obtain an extradition or a suspicion report without a person on the spot. That is why the border guards mainly deal with the men they catch while those are attempting to leave the country.

Kovalchuk adds that in 2024, there were three sentences in criminal cases against border violators in their area. One of them was sentenced to seven years in prison, the other to eight years.

"The prison sentences are mostly suspended. There have been cases where we have arrested people the day after they have been sentenced. If a person is sentenced a second time in such a case, the responsibility is increased, and the probationary period is added to the total," the border guard explains.

The situation is dynamic but under control

Svidomi visited the border village of Onokivtsi in Zakarpattia (Transcarpathia, south-west Ukraine, in the foothills and slopes of the Carpathians, in the Tysa river basin — ed).

Artem Titov, deputy head of the Onokivtsi Border Guard Inspectorate, says that the number of attempted illegal crossings at the site has tripled in May 2024. The border guard attributes this statistic to the warm weather and the new law on mobilisation.

Men mostly try to cross alone, rarely in pairs.

"They think they are less conspicuous. They do not arouse suspicion from the locals and make less noise when they cross. And later, when they run away, it's easier to escape. You don't get distracted because you just run to the border," says Titov.

Since the beginning of 2024, the military has recorded 112 cases of illegal border crossing in the area controlled by the Chop Border Guard Detachment (149.4 km long stretch, total length in the west is 2563 km — ed.). In 85 of these cases, the perpetrators were detained.

‘We can't catch them when they are literally a hundred metres from the border. Then they no longer respond to dogs or warnings,’ the border guard says.

Artem Titov adds that Slovakian border guards do not pass on information about those crossing the border. These people are immediately granted refugee status or temporary protection. The situation is similar on the Hungarian border.

Those detained usually refuse to talk and explain why they are escaping: "There are those who are silent. Some ask for a lawyer. But some admit they wanted to cross [the border], wanted a better life. They say, 'What's wrong with that?'"

After being detained and fined, people often try to cross the border a second time.

Once, Titov recalls, the men used camouflage nets and thermal imagers to cross illegally.

Their thermal imagers were not the most expensive, but they could see 400-500 metres at night. After that, the border guard tells Svidomi there were three or four similar cases in a row.

However, according to the senior lieutenant, men are not only detained when they try to cross the border. Titov recalls a case in which district police officers on patrol spotted two suspicious men. They had no wire cutters or tent; at first glance, it seemed the men had come to rest.

However, after checking their mobile phones, it was discovered that the men were planning to cross the border the following day. On the day of their arrest, they went to a shop to buy beer and pizza.

Titov says that when an offender is caught, he is put in a particular room on the territory of the border guard detachment. Men can stay there for one to three days. During this time, the border guards establish the purpose and details of the crossing (whether they went alone or in an organised group, etc.) and open an administrative case.

The danger of crossing the border directly

No one sees the mountains as a danger, but if you climb alone, you may not know the terrain," explains the Operational Search Department deputy head of the 94th Chop Border Guard Detachment.

In addition, the apparent fatigue and the thin air in the mountains can prevent regaining strength.

"It happens that people get tired, especially those with health problems. Then they call 102 and ask for help: they're lost, they're sick, they can't walk, and it's hard for them," says Oleksandr.

Senior Lieutenant Artem Titov adds that wolves, wild boars and moose are also dangerous when crossing the forest and mountains.

"Now it is hot. The danger is possible dehydration. Anyone who tries to cross the state border takes a minimum of things with them. People can get hypothermia if there's rain or a downpour at night. Also, the local terrain is quite steep. Going up and down after rain is slippery, and you can fall and hurt yourself," Titov concludes.

Liability for service evasion

Ukrainian legislation provides for administrative and criminal liability. Conscription violators can be fined, have their right to drive restricted and be forcibly taken to a Territorial Centres of Recruitment and Social Support (TCR&SS).

The TCR is a body of the Ukrainian military administration responsible for military registration, mobilisation training and conscription.

"Criminal liability arises when a man is not entitled to a deferment, has passed a military medical commission and been found fit for service, and has received a call to go to a training unit, but has not reported without good reason," says Yevheniia Riabeka, a lawyer, former adviser to the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, and head of the Lawyers of the Armed Forces of Ukraine movement.

In this case, violators face three to five years in prison.

Suppose a person violates the new registration and conscription rules, which have been in force since May 18, 2024. In that case, representatives of the TCR can apply to the National Police to arrest the offender and take him to the relevant recruitment centre.

If the summons has already been filled in and its information is accurate, refusal to accept it will be considered a violation of the legislation on mobilisation. The delivery of the summons must be recorded on camera.