Alla Horska. The artist murdered for creating Ukrainian art and fighting for human rights

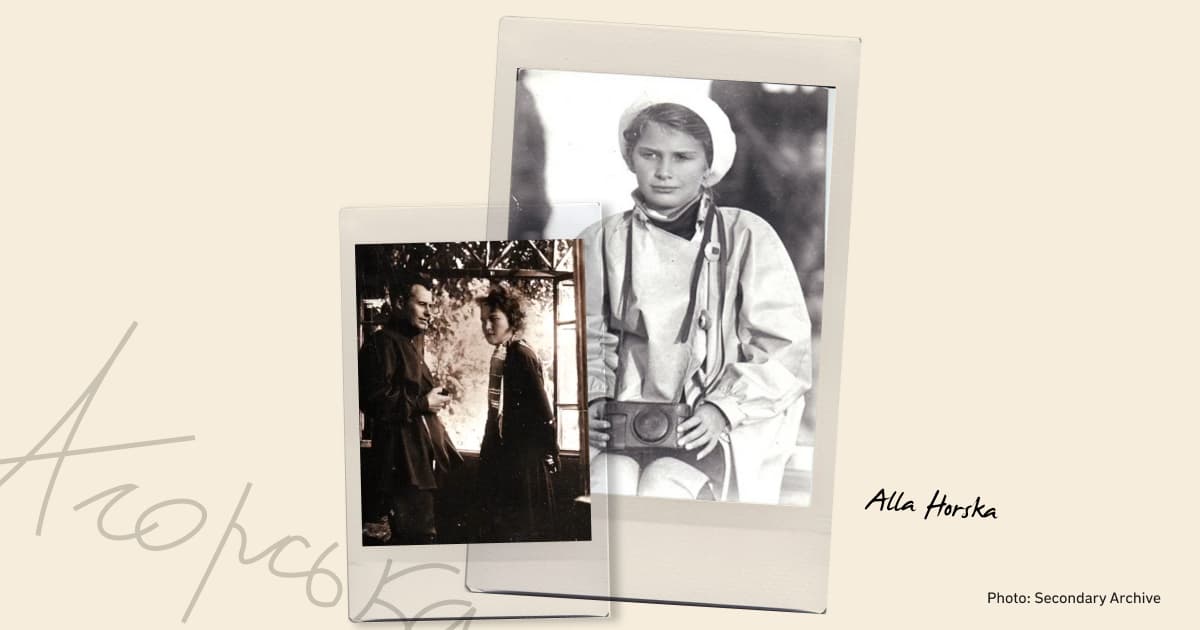

Alla Horska was a Ukrainian artist, monumentalist painter, human rights activist and representative of the Sixtiers movement (a name given in Ukraine to the 1960s group of artists who rejected the principles of social realism with their creativity and refused to let their artworks (paintings, poems, plays, etc.) serve the interests of the Soviet authorities — ed.). Despite the ban on creation and persecution by the Soviet authorities, the artist continued to contribute to Ukrainian culture with her works. As a result, the special services of the USSR killed her at the age of 41 in circumstances that have not been fully clarified.

Read about the artist's life story, her passion for Ukrainian identity, her struggle for human rights and her tragic death.

Russian-speaking family, childhood and moving to Kyiv

Alla Horska was born into a Russian-speaking family on September 18, 1929, in Yalta, Crimea (Qırım). At the time, Ukraine was part of the USSR under the leadership of Joseph Stalin, who embarked on a 30-year programme of Soviet modernisation. The main tasks were industrialisation, the collectivisation of agriculture, and the 'cultural revolution' (education of Soviet citizens). This led to the Holodomor of 1932-1933 and the beginning of mass repression against the intelligentsia.

Alla Horska's father, Oleksandr, was the film studio director in various cities — first in Yalta, later Leningrad (now St Petersburg, Russia), and Alma-Ata (now Almaty, Qazaqstan). Her mother, Olena, initially worked as a nanny in childcare institutions. After moving to Leningrad, she became a costume designer.

Alla and her mother were in blockaded Leningrad during the Second World War. Her father was absent, having left for Mongolia for a film shoot and was unable to return.

In 1943, the family moved to Kyiv, where Oleksandr Horskyi became the Kyiv Film Studio director and received a three-room apartment in the city centre.

In Kyiv, Alla entered the Kyiv Art Secondary School. Those who studied with Alla Horska called her the company's soul and recalled her independent character open and cheerful spirit.

"A few months into her studies, Alla became a leader. She was tall, grey-eyed, a smart girl, gentle, kind, sociable - she brought everyone together," wrote her school friend Halyna Zubchenko in the book The Red Shadow of the Viburnum.

After graduating from school with honours, the girl entered the painting department of the Kyiv Art Institute. The artist's first paintings were dedicated to the work of miners. Her works were immediately included in exhibitions throughout the USSR. Alla could have become a 'Soviet artist', but she was fascinated by Ukrainian identity. In her letters to friends, she boldly shared her thoughts on Ukrainian art:

"I don't like Picasso's art as a manifestation of the world view of the world bourgeoisie. Art without roots, people or nation. (...) But there is the art of Mexico, which represents its people. And I am working to create contemporary Ukrainian art representing my people,"

Alla Horska wrote to her friends.

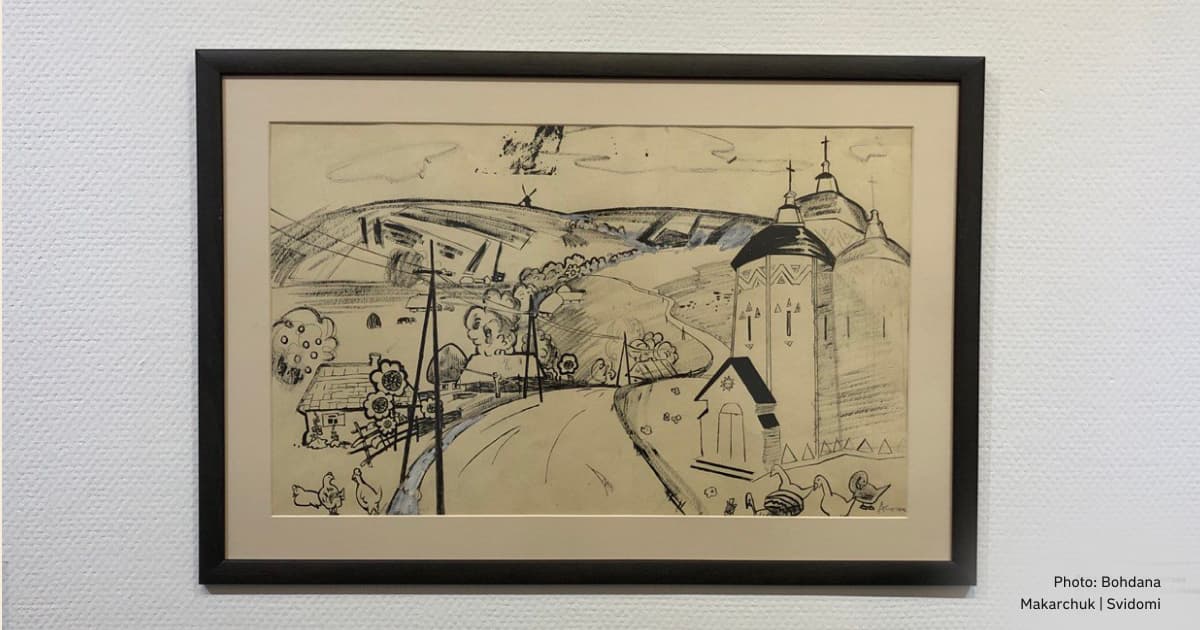

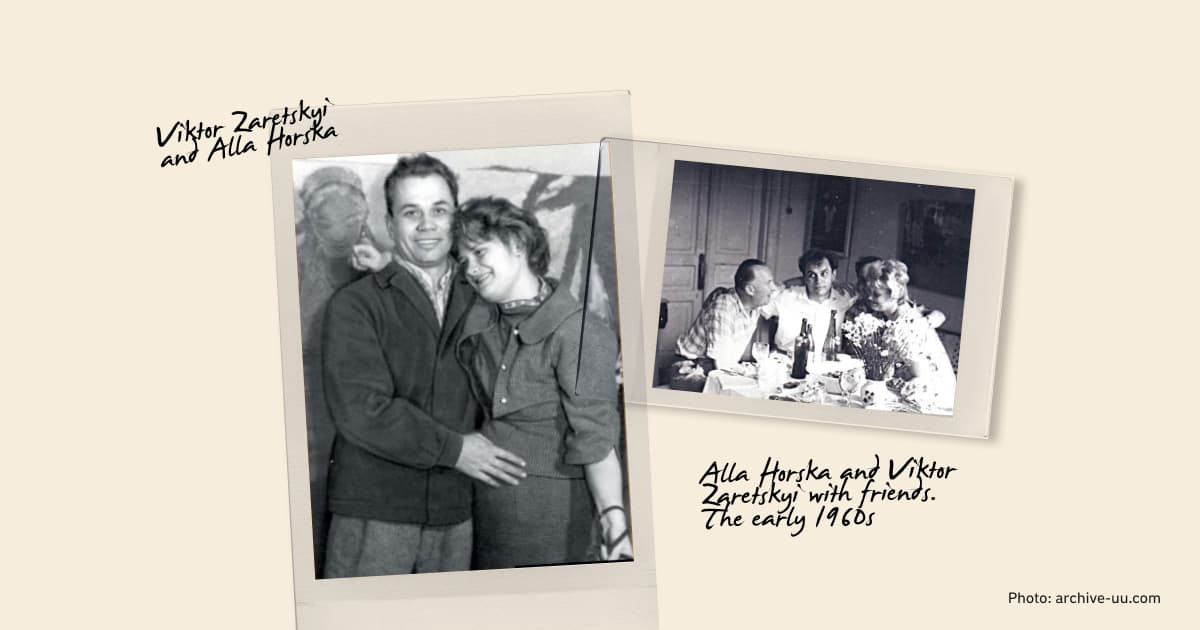

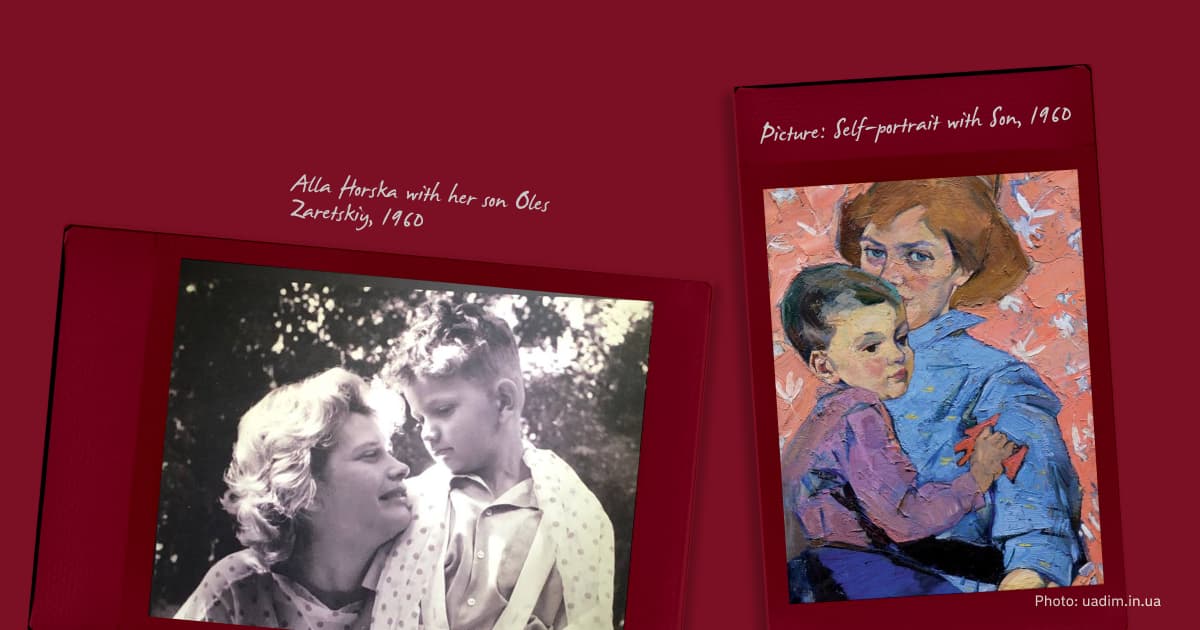

While studying at the institute, Alla Horska met Viktor Zaretskyi, her future husband. The lovers worked in the same studio, took artistic trips around Ukraine and became interested in monumental art together.

Alla Horska's family spoke Russian. As an adult, Alla made a conscious effort to learn Ukrainian, starting with the alphabet. She took lessons from her friend, the journalist Nadiia Svitlychna, wrote dictations, did exercises from textbooks, communicated with her friends in Ukrainian, and read poems by Ukrainian poets.

Nadiia Svitlychna was the sister of the poet Ivan Svitlychnyi, who was first arrested in 1965 for his 'nationalist' activities. Since then, Nadiia had been under surveillance and bugging (in 1972, she was arrested along with her brother and other Ukrainian artists for alleged anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda — ed).

Horska was not involved in Ukrainian culture from birth, but she deliberately became one of those punished for the Ukrainian identity.

Creative Youth Club and the broken stained-glass window Shevchenko. Mother

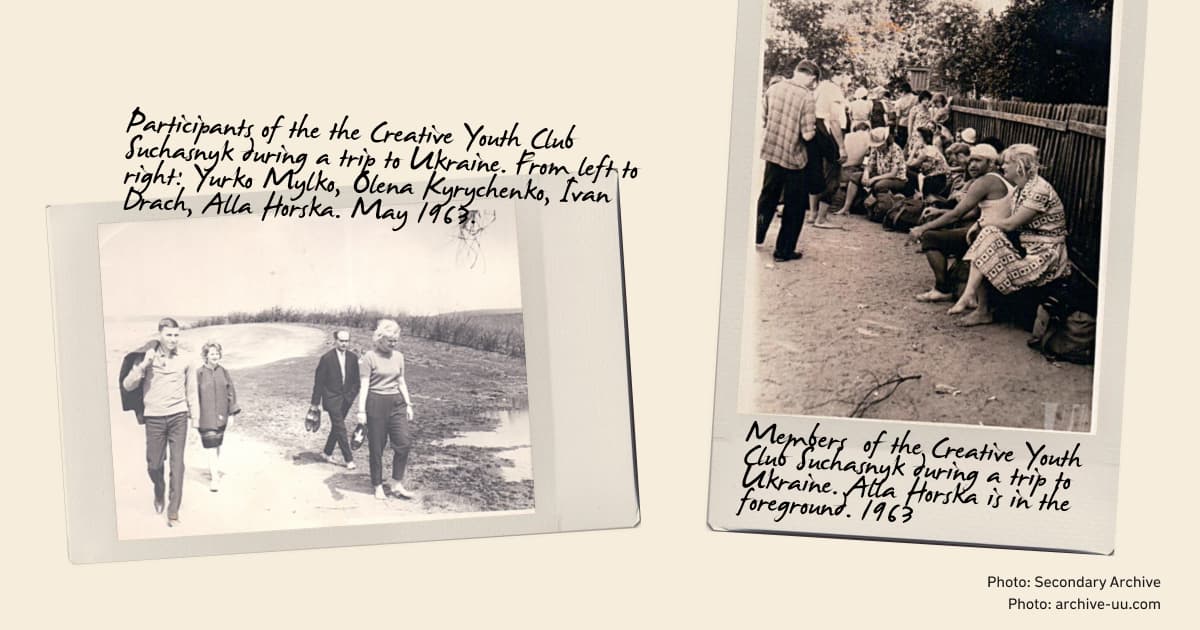

Alla Horska's apartment in the centre of Kyiv quickly became a place where Ukrainian Sixtiers gathered. In 1961-1965, Horska, along with Viktor Zaretskyi, the Ukrainian poets Vasyl Stus, Vasyl Symonenko, Ivan Svitlychnyi and the film director Les Taniuk, became one of the organisers and active members of the Creative Youth Club Suchasnyk. It was the centre of Ukrainian national life in Kyiv.

Her friend Serhii Bilokin described Alla as follows: "A tall, powerful blonde. Smiling, sincere eyes under a bundle of luxurious golden hair. (...) Alla lived among us, but she seemed to belong to another race of people, a titanic race, the crest of the raging Ukrainian element. It was impossible to stop Alla."

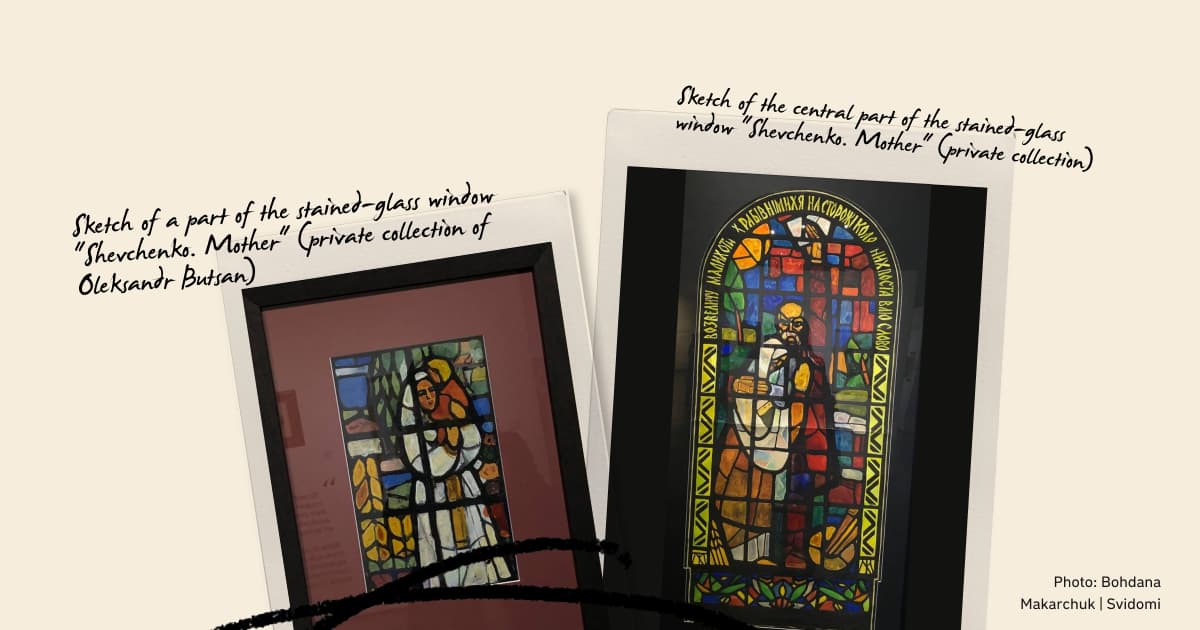

In 1964, on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the birth of the poet and artist Taras Shevchenko, the Rectorate of Kyiv University (in 2024, it is among the best universities in Ukraine — ed.) commissioned to decorate the lobby of the principal university building with a stained-glass window. After the sketches were approved, Alla Horska and other Creative Youth Club artists began working on the scale model.

In the centre of the composition, the artists depicted Taras Shevchenko embracing Mother Ukraine with one hand and holding the Kobzar (a book of his poems published in 1840, one of his most famous works) in the other. The image was completed with the lines: "I will glorify these silent slaves, and my words will stand guard over them!" The work was called Shevchenko. Mother.

After the artists created a life-size model, a scandal erupted. Having seen the model, the USSR party leadership panicked and called the work formalistically hostile. They were concerned: "Why is Mother Ukraine so sad? And why is Ukraine behind bars?"

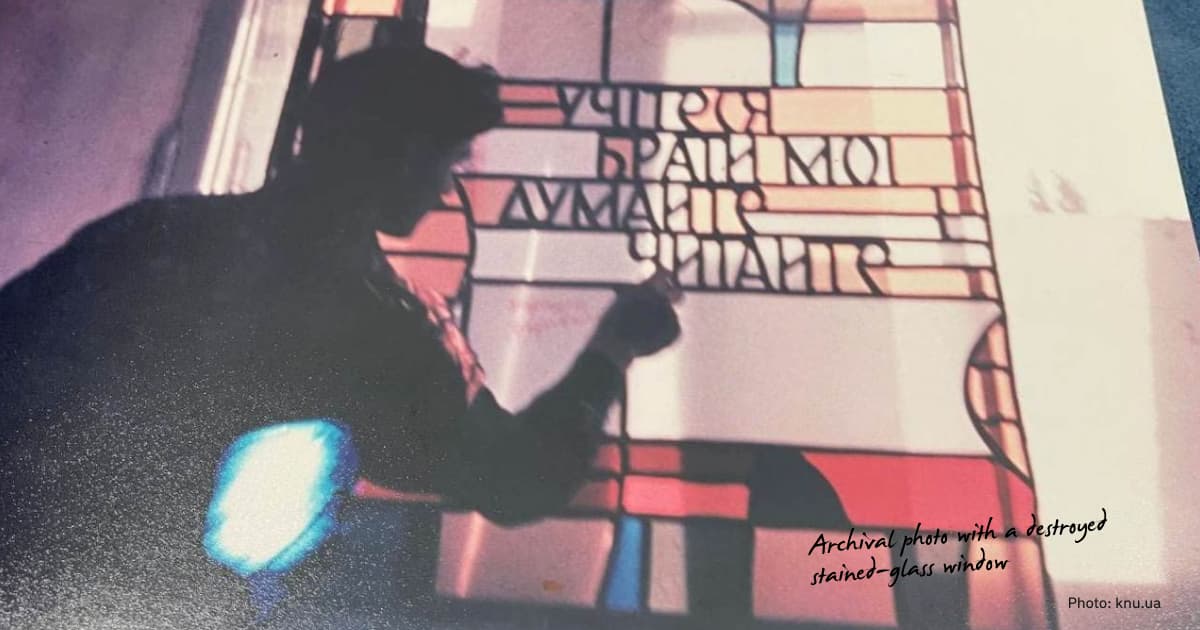

Instead of an official opening, the newly completed stained-glass window was smashed to pieces.

"It was broken on the quiet, and few people had time to see it. The performances were too contradictory and heated. There was too much fire and anger in the window," recalls Serhii Bilokin.

Subsequently, Alla Horska was expelled from the Union of Artists. To renew her membership, she had to go to Moscow. At the same time, the KGB installed a listening device in her apartment. Horska knew she was being watched.

A set designer whose work was never to be seen

In 1962, along with the director Les Taniuk, Horska worked at the Lviv Drama Theatre on the comedy How the Goose Died by the playwright Mykola Kulish (in 1937, he was killed by the Soviet authorities in the Sandomokh forest, together with other Ukrainian intellectuals; 1111 people were killed. The event went down in history as the Great Terror).

Later, they began to work on Mykhailo Stelmakh's play Truth and Falsehood. The Soviet authorities did not allow any of these plays to be staged, and the world never saw Alla Horska's sets.

"The set and costumes, version five... seven... It was a hard, knee-jerk search for myself. Because 'my feet in fashionable shoes cannot find their bare footprint' (Bilokin quotes the Ukrainian poet Ivan Drach). But they did - the best proof of this was the ban on both performances,'

wrote historian Serhii Bilokin.

The beginning of the persecution

Together with Vasyl Symonenko and Les Taniuk, she discovered a mass grave site for Ukrainians shot by the NKVD in the 1930s in Bykivnia (a place where the Soviet authorities secretly buried victims of Stalin's political repression who were shot in Kyiv NKVD prisons — ed). At the time, the Soviet government was conducting a campaign of mass repression against its citizens — the Great Terror. Ukrainian intellectuals were executed for alleged anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.

The most horrifying episode of this event was when the artists saw children playing football on the lawn with a human skull with a bullet hole in it.

Upon returning from Bykivnia, the friends, shocked to the core, wrote an official appeal to the Kyiv authorities demanding that they investigate the incident, begin identifying the dead and organise the burial. But there was no response.

From 1965 to 1968, secret and open trials took place in Ukraine. The first arrests of the Ukrainian intelligentsia after Joseph Stalin's death began, and many of the artist's friends were imprisoned, including the artist Opanas Zalyvakha, one of the authors of the stained glass window Shevchenko. Mother. He was sentenced to five years in a political prison camp for anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda. Alla Horska came to Mordovia in Russia to visit a friend. Throughout his exile, Horska continued to write letters to the artist.

In the second half of the 1960s, Horska was repeatedly interrogated by the KGB. In 1968, Alla Horska signed a letter of protest to the leadership of the USSR, signed by 139 figures from the world of science and culture, against the persecution, arrests and trials of Ukrainian intellectuals. Horska was subsequently expelled from the Union of Artists for the second time.

Alla Horska's son wrote that a piece of paper pinned up in the house said, "On the roof, the rooster is crowing. It's hard to sit on the stairs, and Arnold keeps wondering where Mrs Horska is wandering."

It was about the agent who spied on the artist sitting on the wooden stairs to their house's attic. Horska's friends, either jokingly or seriously, called him Arnold and often greeted him.

The artist actively helped her friends with money. She gave some of the money she earned to the families of political prisoners or those returning from political prison camps.

While waiting for Zalyvakha to return from the camp, Horska organised friends to buy clothes for him. She also hired a cafe to celebrate her friend's return. This meeting was their last — within a few months, Alla Horska would be murdered.

Alla Horska's death

On November 28, 1970, Alla Horska left her home and went to her father-in-law Ivan Zaretskyi's house. She never returned. Later, her husband Viktor Zaretskyi went to fetch his wife but found his father's house locked. Despite the family's concerns, the police refused to open the house.

On November 29, Ivan Zaretskyi's body was found on the railway tracks with his head cut off. On December 2, the police finally entered the house and found Alla Horska's body in the cellar, killed by an axe to the back of the head. These were the details of the tragedy that Horska's son, Oles Zaretskyi, described.

The investigation concluded that 'the father-in-law allegedly killed his daughter-in-law Alla Horska out of personal animosity and then committed suicide'. The artist's friend Serhii Bilokin recalled that Alla had met a stranger with whom she was talking in Kyiv's Shevchenko Park before her death.

Horska's family and friends were convinced that it was a political murder. No one investigated the circumstances of the artist's death. However, there were many inconsistencies in the case: Ivan Zaretskyi was an elderly man, and Horska was killed "professionally, with one blow", as the medical expert stated.

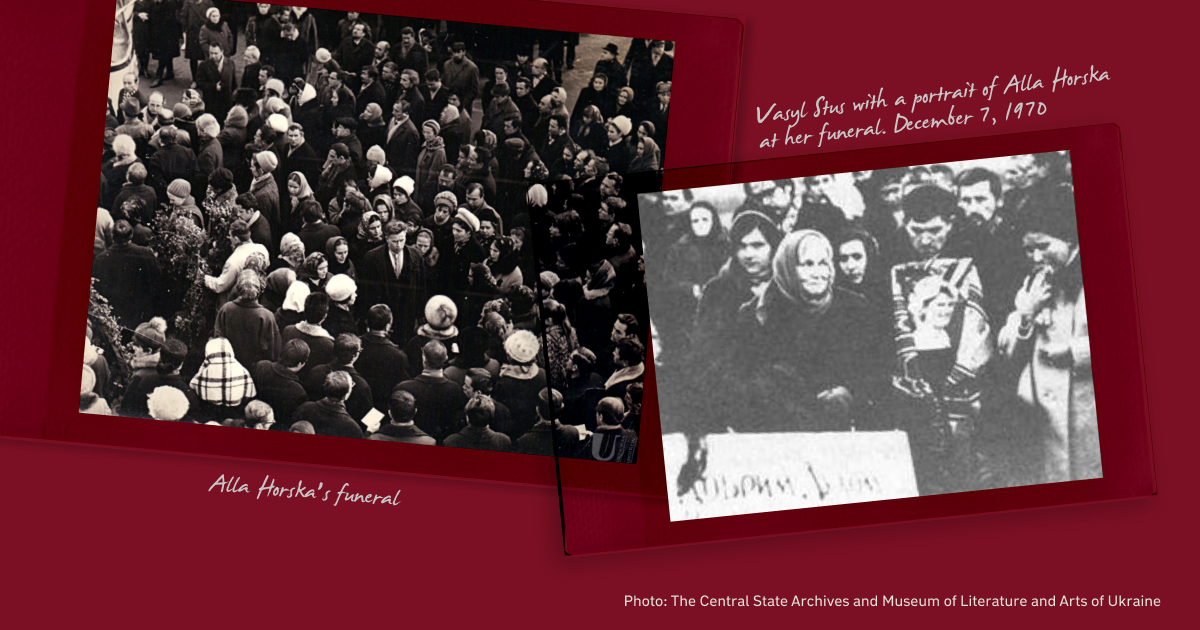

At that time, proving the truth or achieving justice was impossible. On December 7, 1970, Alla Horska's funeral in Kyiv turned into a protest rally against the ruling Communist regime. The Soviet authorities kept a record of all those who attended the funeral and added them to a list of those who allegedly 'threatened the security of the USSR'.

"We buried her forever on December 7, 1970, at the Berkivtsi cemetery in Kyiv, on a dull winter's day. She was buried in an oak coffin made in a film studio for some film. The coffin was not opened,"

recalls Serhii Bilokin, a friend of the artist.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Alla Horska's son, Oleksii, took up the search for the truth. He gathered information about his mother's life, writing to and meeting her friends, colleagues and surviving political prisoners. Later, he gained access to declassified material, which allowed him to prove that his mother and grandfather had been killed on the orders of the KGB.

Horska's mosaics destroyed by Russia in Mariupol

In the summer of 2022, after the full-scale invasion, Russian troops destroyed the Tree of Life and Boryviter (Falco) mosaics by Alla Horska and Viktor Zaretskyi in the temporarily occupied Mariupol. Created in 1967, both works were experimental, as the artists used non-standard materials: slag glass ceramics and metal. These works were considered the pearls of Mariupol's monumental art collection.