There is no PMC Redan. But what is it and what has this situation taught us?

That's right, PMC Redan, which has been in the news in recent days, does not exist. News headlines might give the impression that a new youth subculture has emerged in Ukraine. Its members have long hair, use the spider symbol as their emblem, and watch Japanese anime.

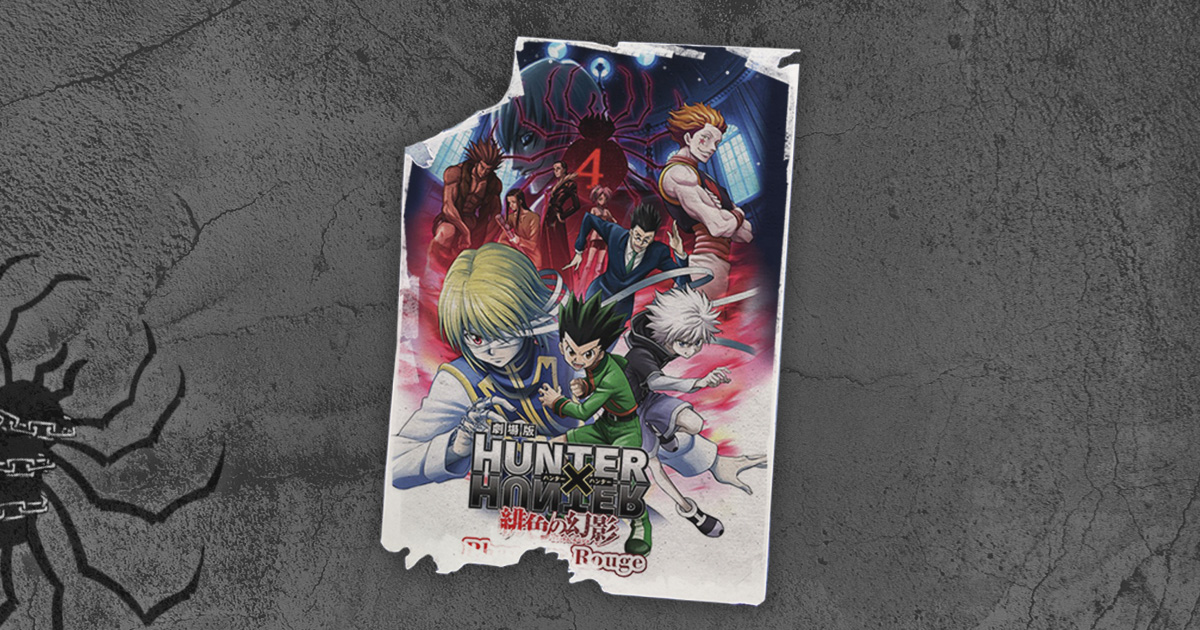

The very name of the movement, which originated in Russia, comes from the "Redan" group from the anime "Hunter × Hunter." Redan members oppose the subculture of football fans and arrange group fights against them. Redan meetings were apparently held in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Poltava, and other cities, but there have been no reports of fights.

In reality, it's not that simple. A 16-year-old from Dnipro, who founded one of the channels dedicated to Redan, explained to the police that this movement does not actually exist in Ukraine. Why did he create the channel then? To make money. From the FSB? No, selling advertising. The guy planned to quickly gain followers due to the hype around the topic and advertise various resources for $10.

However, the police in the Kharkiv region alone identified 245 people involved in the "movement." Moreover, Redan originated in Russia. This is an obvious Russian provocation, right? Perhaps. And perhaps it is something else.

This "movement" began to unfold spontaneously in Russia about a week ago. It all possibly started with a fight in a shopping center between two groups of teenagers. Allegedly, representatives of hooligan football culture attacked anime fans. The advantage was on the side of the former, so the latter decided to take revenge.

They mobilized other anime fans using anime social media pages. As a result, on February 20, the first mass fight between the groups took place. Russian security forces began detaining those involved in the fights.

The first reports about Redan in Ukraine appeared on February 25. In other words, the Russian special services had only a few days to come up with and implement a plan to destabilize Ukraine using anime. Of course, the enemy should not be underestimated, but it does not sound too realistic.

In addition, most of the photos published by the National Police do not have Redan symbols or other features characteristic of this culture. Most of them are just teenagers. It is also noteworthy that Redan members were detained not only in Russia and Ukraine. The Belarusian security forces detained 200 people associated with the Redan movement in a Gomel shopping center.

Russian propagandists claim that the Special Operations Forces of the Ukrainian Armed Forces used the already established youth movement to cause unrest in Russia. Ukrainian police say that the emergence of Redan in Ukraine is a Russian information and psychological operation. In Belarus, no one is saying anything. There is very little verified information.

Videos of Ukrainian teenagers in Rivne and Poltava allegedly chanting "no to war" are circulating on the Internet. So far, it has not been possible to confirm their authenticity. Even the aforementioned "prime suspect" from Dnipro explains that he wanted to make money from advertising, not fulfill the FSB tasks.

Despite all the absurdity, this situation can teach a lot. Here are the three most important lessons.

Lesson one: Russian information influence has not disappeared

Russia's full-scale invasion and tens of thousands of Ukrainians killed did not completely undo 300 years of Russian cultural dominance. Russian propaganda has lost its audience, but Russia still has a "soft" and decentralized influence on Ukraine.

Of course, it is easy to blame minors — they are not yet formed individuals, easy prey for the enemy. However, this understates the problem.

"Detektor-media" publication established that among the 100 most popular Telegram channels in Ukraine, about 10% have an openly pro-Russian agenda. One of such channels writes about Odesa regional news. It has 660,000 followers. Of course, Russians make up some part of the audience of this channel. But it is naïve to think that the rest are unaware teenagers.

Russian informational influence can only be overcome by targeted action. The war did not automatically put anything "in its place." Accusing "teenagers," "Easterners," or "pensioners" of consuming Russian content only understates the problem.

The only way to overcome the past is to change your own habits and encourage your family and friends to do so. If you are too lazy to do so, then don't be surprised by the following headlines of Russian propaganda: "The emergence of the PMC Redan in Ukraine once again proved that we are one nation."

Lesson two: The change of generations in Russia will not change anything for Ukraine

Putin now holds the record for the number of people who want him dead. Of course, this will lead to an imbalance of the regime; perhaps, Ukraine will get time to regain strength. However, violence in modern Russian society is the norm, not a deviation. Therefore, it is unlikely that the next generations of Russian elites will differ from the previous ones.

Svidomi has already talked about Yunarmia, a Russian youth organization that trains motivated soldiers out of children for future military campaigns. However, this is a state initiative, which means that checking off a plan, stealing money, or doing nothing is much more interesting for its functionaries than conducting activities that threaten Ukraine.

The problem is bigger. It's not just about the fights that Redan causes. People are always fighting everywhere. The appearance of the term "private military company" in the name of the movement is striking. After all, initially the social media pages about Redan in particular and anime in general did not contain the abbreviation "PMC." It was added later because many Russian teenagers are not critical of the PMC Wagner's advertising.

In their videos, Prigozhin's propaganda resources present war as a computer game with adrenaline, honour, and violence. Minors do not necessarily have to be immediately eager to join the ranks of mercenaries.

However, along with this propaganda, two principles are internalised in society: 1) everything in the world can be bought and sold; 2) there is nothing wrong with violence.

These ideas resonate with the cornerstones of Russian foreign policy. Russian society is so saturated with them that "PMC" emerges spontaneously as part of a teenage subculture.

Lesson three: Spontaneous mobilisation is possible

Not all that happens in the world has a rational reason. Sometimes, when faced with the irrational, people tend to think of a rational explanation.

Sometimes big social movements start with something small, especially in authoritarian societies. For example, the Soviet experience. On June 16, 1963, a tram was travelling through the Sotsmisto district of Kryvyi Rih. A drunk soldier was smoking a cigarette and blowing smoke in the face of a female passenger.

There was an equally drunk police officer on the tram. At the request of the passengers, he tried to force the soldier to stop. During the tram stop, the policeman tried to detain the soldier, although he had no right to do so. The soldier started to run away. The police officer started shooting and wounded the passers-by. The security forces caught the soldier and took him away to the police station.

People who had already changed their attitude to the situation gathered near the police station and began to demand the release of the soldier. This started a mass unrest in which seven people were killed and 86 were injured.

Thus, even spontaneous initiatives can have a start provoked by external forces. To prove this thesis, it is necessary to possess evidence. Currently, there is none.

Future threats

Although there is no clear Russian trace of Redan in Ukraine, Russian special services may try to organize other groups of minors in the future.

The Soviet secret services constantly tried to take control of international youth organizations, or even better — to infiltrate such movements in NATO countries. This continued during "perestroika": for example, in 1987, the KGB tried to take over youth organizations in the Democratic Republic of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). If the Soviet secret services were active even there, it is clear that the Russians will try to conduct similar operations now.