Honouring the victims of the Crimean Tatar deportation. 80 years later

"On May 18, two soldiers came and told us that the family had 15 minutes to pack: take the most necessary things and come to the cemetery. My grandmother didn't understand anything then, but she had a bad feeling. She thought they were going to be executed. After the meeting, they started putting people into wagons. Members of the same family were put on different trains and deported to different destinations. So that day was the last time my grandmother saw some of her relatives," Alim Aliev, a Crimean Tatar, Deputy Director General of the Ukrainian Institute, tells Svidomi about his family's experience in Crimea (Qırım) in 1944.

At dawn, the Soviet Union began an operation to deport the indigenous population of Crimea from the peninsula. In a matter of days, some 200,000 Crimean Tatars were forcibly deported, many of whom died or were never able to return to their homes.

In this article, we honour the memory of the victims of the genocide of the Crimean Tatar people and recall the events that took place 80 years ago.

Deportation Timeline

The deportation occurred while the Second World War was still ongoing. German troops occupied Crimea (Qırım) in 1941. The Soviet army pushed them out in 1944. The last Nazi military forces surrendered on May 12, and a week later, the large-scale deportation of the indigenous people of Crimea began.

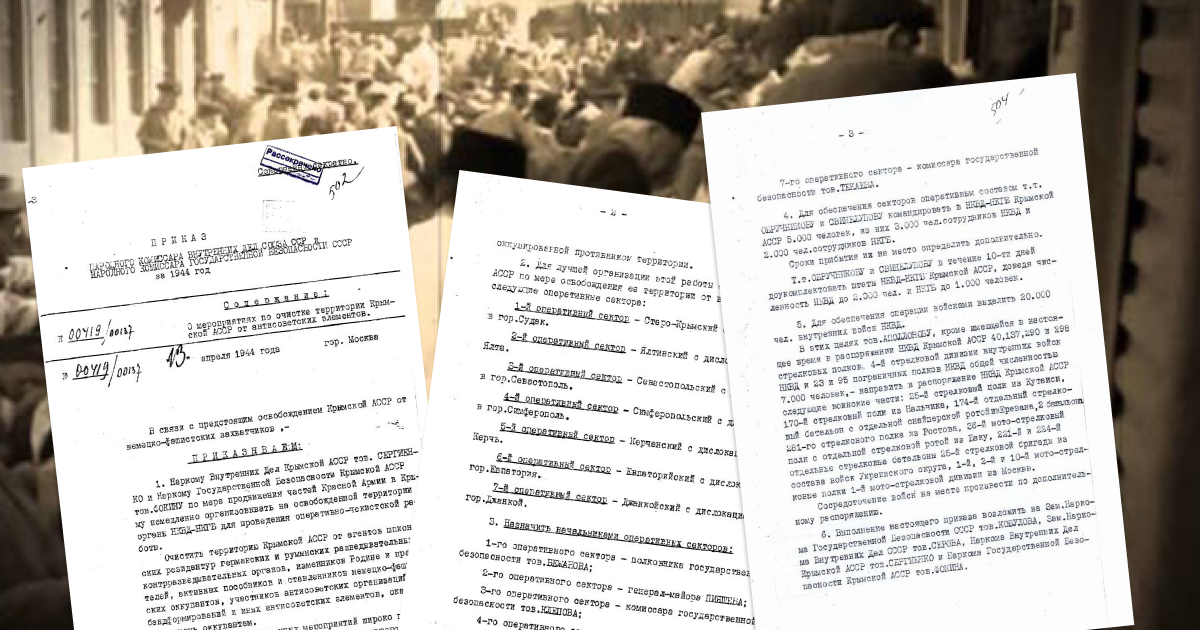

On May 11, 1944, the State Defense Committee of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) adopted a secret decree On the Crimean Tatars. In it, the Crimean Tatar population was accused of alleged massive treason and collaboration with the Nazi occupiers. Therefore, all Crimean Tatars were ordered to be evicted from Crimea.

The main round of deportation began at dawn on May 18 and ended on May 20, 1944. It involved 32,000 NKVD officers (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs, abbreviated NKVD, was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union, the ancestor of the KGB — ed.).

The deportees had a few minutes to half an hour to pack and were officially allowed to take up to 500 kg of belongings per family. In reality, people managed to pack only "hand luggage," if anything. The state would confiscate all remaining property.

In the first two days, 191,044 people were deported from Crimea. About 8,000 died during the transfer. The most common causes of death were thirst and typhoid. The dead were thrown out of the trains along the way and were not allowed to be buried.

The total number of expelled Crimean Tatars amounted to about 200 thousand people: more than 183 thousand went to Central Asia to "special settlements", 5 thousand went to forced labour in the Moscow Coal Trust, and 6 thousand to front-line reserve camps and six more to the Gulag (a system of labour camps maintained in the Soviet Union — ed.).

The USSR also expelled more than 40,000 Bulgarians, Armenians, Greeks, Turks, and Roma from Crimea.

On July 4, 1944, the NKVD officially informed the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin that the special operation to resettle the Crimean Tatars was over. But later, it turned out that one of the units did not deport the people who lived on Arabat Spit (Arabat Beli). On July 20, they were put into an old boat and drowned in the Sea of Azov. Those who tried to escape were killed with machine guns.

In the first three years after the deportation, according to official estimates, 20 to 25% of all Crimean Tatars died of hunger, exhaustion and disease. According to the self-census of the Crimean Tatar national movement, this number amounted to 46%.

The USSR deported the vast majority of Crimean Tatars to so-called "special settlements" in Uzbekistan, Qazaqstan and Tajikistan. These settlements were fenced with barbed wire and resembled labour camps. Those who left their special settlements without permission from the NKVD could be imprisoned for 20 years.

In 1948, Moscow recognised the Crimean Tatars as permanent migrants.

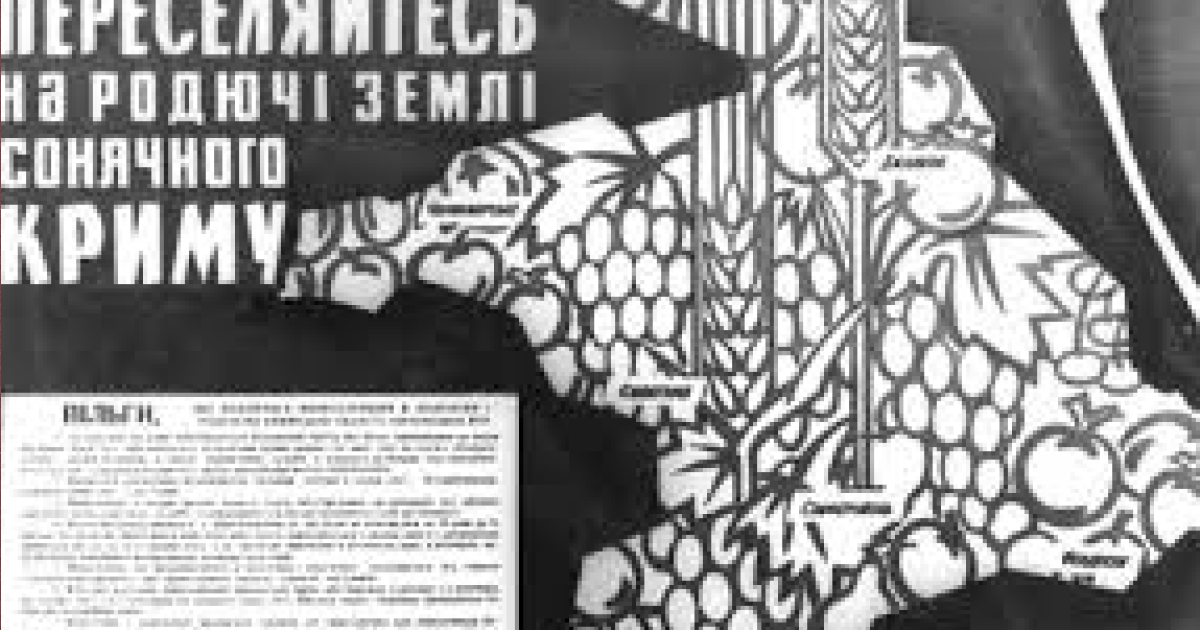

The ethnic composition of Crimea changed dramatically. According to the 1959 census, 71%of the peninsula's population was Russian, and another 22 % was Ukrainian. There is no data on the Crimean Tatars.

Without its indigenous population, the peninsula began to decline. In 1954, after the death of Joseph Stalin, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR issued a decree transferring the Crimean region from the Russian SFSR to the Ukrainian SSR to revive the peninsula's economy.

Crimean Tatars were not allowed to return to Crimea until 1989. Despite the long and difficult journey, those who were able to return to their homes found other people living in their houses.

"When we came back, the attitude from the locals was negative, and they perceived us as 'oh, the Tatarva (a derogatory name for Tatars — ed) has returned'. When we returned home, the local people knew nothing about us except stereotypes. After my grandfather's return, he visited his parents' house in Bakhchysarai (Bağçasaray). Nothing had changed in the house, not even the fence. It had been there for 45 years. This means that those who lived in their houses never felt that Crimea was their home," Alim Aliev said.

A new occupation, Eurovision and the full-scale invasion

When Ukraine declared its independence in 1991, Crimea became part of it as an autonomous republic. Russia had been occupying Crimea for a long time, gradually and consistently, either by deploying its Black Sea Fleet or by occupying a single island.

The crucial period in Crimea's modern history was 2014, when, following the Revolution of Dignity and the escape of President Viktor Yanukovych, pro-Russian sentiment in Crimea intensified. The peninsula's leadership publicly stated they would consider secession from Ukraine, and the Russian military intensified its movements.

The Crimean Tatars sided with Ukraine, and the Mejlis, the representative body of the Crimean Tatars, organised pro-Ukrainian rallies in front of the Crimean parliament.

Nevertheless, the Russians occupied Crimea and held an illegal referendum. Neither Ukraine nor the democratic world recognised this referendum and its results. Since the occupation began, the Crimean people have been subjected to renewed repression.

The "authorities" of the temporary occupation have searched the homes of Crimean Tatars and accused them of alleged terrorism and involvement in the international Muslim political party Hizb ut-Tahrir, which is considered a terrorist organisation in Russia (it’s legal in Ukraine and most countries — ed.).

The Mission of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea confirms 209 illegally imprisoned Ukrainian citizens, 126 of whom are Crimean Tatars.

Although no direct deportations are taking place, the Russians are doing everything possible to make Crimean Tatars want to leave Crimea or to ban them from entering the peninsula, such as the leader of the Crimean Tatar movement, Mustafa Dzhemilev, and the head of the Mejlis, Refat Chubarov.

In 2015, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine recognised the forced 1944 deportation as an act of genocide against the Crimean Tatars.

A week ago, Sweden hosted the largest song contest in Europe. In 2016, the Eurovision Song Contest was also held in Sweden, and Jamala won with the song 1944.

Jamala is a Crimean Tatar who knows about the deportation, not from history books but from the story of her family. She was born in Kyrgyzstan because that's where her family was deported to.

«Yaşlığıma toyalmadım // Men bu yerde yaşalmadım» ("I couldn’t spend my youth there // Because you took away my peace"), Jamala sang on stage at the Eurovision Song Contest. She is still unable to spend her youth in Crimea because of the occupation. Last year, a Moscow court arrested Jamala in absentia for allegedly spreading lies about the Russian army.