Refat Chubarov: "In the same way the state will take care of the preservation and development of the Ukrainian nation, it should also take care of the Qırımtatarlar, indigenous people"

On June 26, Ukraine celebrates the Qırımtatar Flag Day. Under the occupation of Qirim, the Qırımtatarlar are subjected to constant harassment: many representatives are accused of alleged terrorism, the occupation authorities of Qirim suppress any form of exercise of the Qırımtatarlar's right to peaceful assembly, the activities of the Qırımtatar Milliy Meclisi are banned, etc.

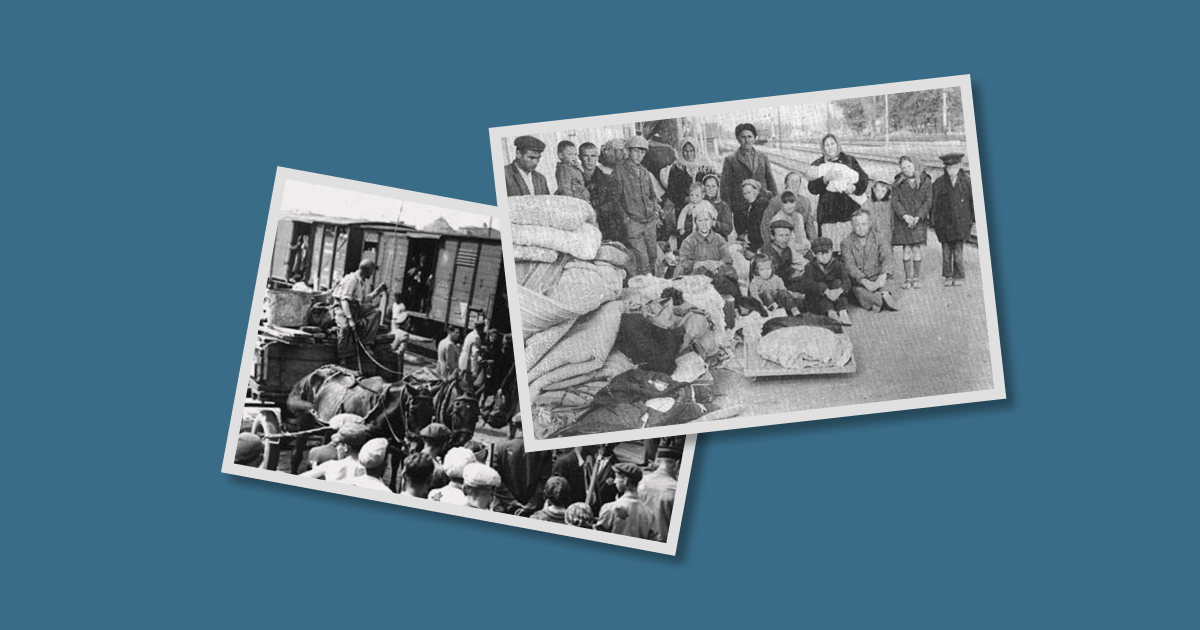

Such a policy towards this people has a lengthy historical background. In 1944, the Soviet authorities deported Qırımtatarlar from Qirim to distant regions of the USSR, changed their names, and forbade them to settle in their homes upon returning to Qirim.

Svidomi spoke to Refat Chubarov, the head of the Qırımtatar Milliy Meclisi, about the consequences of the Kakhovka HPP explosion for Qirim, how Russian behaviour on the peninsula has changed since the start of the full-scale invasion, the prospects for the release of political prisoners, and whether Qirim should remain autonomous after de-occupation.

Tell us about your family. What was their experience of deportation in 1944?

I was born in 1957 in Samarkand [a city in Oʻzbekiston - ed.]. My father, Abdurahman, was 13 years old when he and his family were deported. My mother was 11. They grew up in exile.

In 1968, my parents were able to return to Crimea, so I grew up there from the age of 11. People often ask me whether Qırımtatarlar were allowed to come back. No, Qırımtatarlar were not allowed to return to Qirim. Still, in 1968-69, the Soviet authorities specifically allowed several hundred families to return to Qirım to reduce the heat of the Qırımtatar national movement.

Another reason was to stop the debate in the international communist movement, where some communist parties, including the Italian and French ones, pointed out to Moscow that the Soviet Union had not overcome the consequences of Stalin's crimes.

But no one was allowed to settle where they had lived before the deportation. Everyone was resettled in the steppe parts of Qirim. The main principle of resettlement was that the number of Qırımtatarlar in one settlement should not exceed 5-8 families.

On June 6, the Russians blew up the Kakhovka HPP. What are the consequences for Qirim?

Despite its small territory [27,000 square kilometres - ed.], Qirim has a diverse landscape: mountains, foothills, and steppe. The steppe Qirim remained a virgin territory [unchanged by human activity — ed.] until the 60s. As a rule, people there were engaged in sheep farming.

In the early 60s, the Soviet authorities developed a programme to supply water from the Dnipro River to Qirim to use these lands. The project of the North Crimean Canal was launched under Khrushchev. The supply of the Dnipro water changed agriculture in Qirim. It made it possible to grow orchards, plant vineyards, and wheat.

During the occupation, Russians built military bases and many high-rise buildings in Qirim. In 9 years, 9 million new people have been settled on the peninsula [Svidomi could not confirm this figure; the Mission of the President of Ukraine in ARC reported that about 800,000 Russians had moved to Qirim during the occupation — ed.]. All of this requires water and other water-related services.

If there had been no resettlement of a large number of people and no significant number of military garrisons, there would have been enough drinking water from Qirim's springs for people but not for agriculture. Therefore, the cessation of water supplies through the North Crimean Canal is challenging.

The dam needs to be rebuilt for the water to start flowing again [the North Crimean Canal starts from the Kakhovka Reservoir. Before the occupation, the canal provided 85% of freshwater needs. In April 2014, Ukraine stopped supplying water to Qirim through the canal. On 24 February 2022, the Russians seized the main building of the canal in Tavriisk, Kherson region, and the Kakhovka HPP, after which they resumed the water supply. After the Kakhovka HPP was blown up and the Kakhovka reservoir was shallowed, the water supply to Qirim stopped — ed.].

Water is essential for Qirim to develop in a balanced way as a resort area and for agriculture to grow. Qirim cannot survive without the Dnipro water.

How long will the water supply problems in Qirim last? Do the Russian authorities have alternative ways of providing water?

No, not at the moment. The Russians had programmes and plans to extract water from the bottom of the Azov Sea. In the past years, they conducted research and tried experimental drilling, but the water was salty. Since they reached the Dnipro water last year, they stopped researching and drilling wells at the bottom of the Azov Sea.

Will they return to this idea? I think not. They have no time for that now. They need to figure out how to save themselves, not how to maintain the occupied Qirim.

How noticeable are these water problems for the population?

The dam blowing up does not directly affect the lack of water or any other problems with the water supply. There is enough water in the reservoirs in Crimea for this year, as there were frequent rains in the spring. But there is a problem with the agricultural sector. The Russians have planted a lot of rice, which will not ripen because it requires a lot of water.

The situation next year will depend on the weather. Crimea has a drought every 5-6 years.

What is the current mood like among Russians? How accurate are the reports that they are evacuating their families?

The Russian troops, the occupation administration, and those Russians who settled after the occupation know that they will have to leave Qirim. Some may still be waiting for something, but the most cautious decide to evacuate and prepare backup sites in Russia.

It is known for sure that the heads of the punitive structures, the FSS, the prosecutor's office and the Investigative Committee have evacuated their families. Like no one else, they have a clear vision of what is happening on the battlefield and that the advance of the Ukrainian Armed Forces towards Qirim is inevitable.

For us, the critical thing is that Qirim is no longer attractive to those Russian citizens planning to move there. I can give you an example of Köktöbel. Only 50% of tourist facilities have been opened there. But even these establishments have no visitors. This year's holiday season has failed because Qirim has become a frontline territory.

Comparing the moods among Russians before and after Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, how much have they changed?

It all depended on what was happening in and around Qirim. The first stage of the large-scale invasion was welcomed by pro-Russian Qirim residents, who thought that Russia would quickly occupy the rest of Ukraine and eliminate the Ukrainian government.

When Ukrainian troops de-occupied the northern regions in April 2022, the mood in Qirim changed. The awareness that the war had broken into Qirim came in August 2022, when the military airfield in Novofedorivka was attacked. That was when the first explosions occurred.

A few days later, a large ammunition depot near Canköy was destroyed [at the same time, a record number of people left Qirim - about 38.3 thousand cars - ed.]. This made Russia's fanatical supporters sober up. They realised that the war was already where they lived.

Then the constant drone attacks on targets began, including the Russian Black Sea Fleet headquarters in Aqyar. It makes people in Qirim realise that the Russians will leave the peninsula. The idea that the Russians will flee Qirim and the Ukrainian Armed Forces will come here is encouraging for the part of the population that remains loyal to the Ukrainian state.

Do the frequent reports of UAVs being used in Qirim affect the mood there? Can the Russians use them to boost mobilisation?

The Russian occupation authorities are trying to use anything to spread propaganda, to put different messages in people's heads. But still, everyone in Qirim, including Russia's supporters, is aware that the peninsula is not Russian land. Russia's supporters may lie to others, but they know how Russian troops invaded the peninsula and the brutal terms in which they held what they called a "referendum".

For Qirim, using these reports as a reason for mobilisation does not work. Therefore, drones play only one role — to deepen the awareness that Qirim is a frontline territory. The use of long-range missiles or other similar weapons against military targets will encourage Russians to leave Qirim.

Media used to report that tens of thousands of Qırımtatarlar were leaving the peninsula to avoid mobilisation. What about these people now? What about those who could not leave the peninsula?

In September last year, Russia announced the so-called partial mobilisation. They mainly mobilised people in the occupied territories to eliminate people not loyal to the Russian occupation. They used them as cannon fodder. It is illegal under international law: a country that has occupied the territory of another state cannot carry out either voluntary or forced mobilisation of the inhabitants of that territory.

Citizens of Ukraine living in the occupied territories understand that they will be used as killers of their fellow citizens. Therefore, they have not found any other way to avoid this mobilisation [than leave].

According to our data, we are talking about six - seven to nine thousand people. Those whose documents are in order immediately go to countries offering them asylum. Those whose papers are incomplete or overdue apply to Ukrainian consulates and embassies abroad.

Many Qırımtatarlar and other Qirim residents have gone to Qazaqsatan, as they can enter the country with internal Ukrainian or Russian passports. There, they applied to the Ukrainian consulate with a request to issue Ukrainian passports.

Many people we do not know could not resist the mobilisation, so they were forcibly mobilised into the Russian army. We do not know how many of them are Qırımtatarlar. We can only monitor those who are being buried. Among the fallen soldiers buried in Qirim, there are both Qırımtatarlar and ethnic Ukrainians.

Will Ukraine prosecute those mobilised?

If these people have not committed specific crimes, they will be considered victims. In the army, such a person is sometimes forced to follow orders. Still, unless it is established by evidence that this person's actions led to consequences that entail criminal liability, they will be considered a victim.

The Mission of the President of Ukraine in ARC reported that Russians had illegally imprisoned 16 civilian journalists. What are the prospects for their release? What about the Qırımtatarlar accused of alleged terrorism?

The number of political prisoners in Qirim varies but is currently around 200. It fluctuates, there is evidence of 185, and another is of 190. Among them are both professional and civic journalists. This phenomenon arose in Qirim when almost all journalists could not practise their profession.

The absence of a significant number of professional, unbiased and honest journalists caused such people to cover what was happening in Qirim [earlier, Svidomi wrote about the phenomenon of civic journalists in Qirim - ed.]. Among them are professional journalists such as Vladyslav Yesypenko or the first deputy chairman of the Qırımtatar Milliy Meclisi Nariman Dzhelial.

Russia avoids any negotiations. They have adopted the position that the political prisoners are allegedly their citizens, saying that we have no right to interfere in 'Russian internal affairs'. They remind us of Russia's unofficial position when Ukraine offers to exchange Qirim political prisoners.

I assume Russia is raising the price of political prisoners because they are mostly Qırımtatarlar. The Russians understand how important these people are for our country's image. People who did not bow their heads to the occupiers suffered physical and moral torture — people who retained their honour and dignity.

I think the Russians expect a situation when they want to release influential or valuable people. There are few initiative proposals [to exchange their citizens] from Russia, like in the case of Medvedchuk. They await situations when they need an exchange, and then they will offer Qirim political prisoners.

Have there been any attempts by the Ukrainian side to engage in a dialogue with Turkey on releasing political prisoners?

The President of Türkiye and I discussed various formats. One of the latest proposals from the Ukrainian side was to release Muslims. Together with the Turkish side, we offered to exchange Muslim prisoners. The Russians did not agree to this.

What should Ukraine do with Russians and collaborators in Qirim after de-occupation?

It should be done following the law. Another thing is that the current Ukrainian legislation needs to be improved.

All those who committed crimes, especially those Ukrainian citizens with specific obligations to the state, must be held accountable. These include the military, representatives of law enforcement agencies, and judges.

Russian citizens who settled in Qirim violating the Ukrainian legislation, i.e. after February 27, 2014, should be expelled from Qirim.

The date of February 27, 2014, is important because the European Court of Human Rights has determined that Russia has exercised effective control over Qirim since that day. However, the Russians wanted the Court to stick to March 20.

They wanted to convince the court that from the end of February to March 16, the people of Qirim decided [whether to remain part of Ukraine or not], held a "referendum", and asked Russia to join them. Then, according to Moscow, everything was supposed to be in line with international law. But the Court chose the date of February 27, when Russians entered the territory of Qirim with the so-called "little green men" and seized the Supreme Council and the Council of Ministers of Qirim.

When I talk about the need to improve the legislation of Ukraine, I am referring to this category of people [Russians who illegally settled in Qirim - ed.]. According to the current legislation, a foreigner or stateless person who illegally stays on the territory of Ukraine is subject to punishment. Such a person may be expelled in appropriate cases, but this is considered individually. This procedure is not acceptable for Qirim.

There are millions of such people there. How can we ensure such a procedure for them? Therefore, we call on the Verkhovna Rada to adopt amendments to the legislation that would provide for a particular expulsion procedure. Many Russians will try to stay in Qirim because they have invested there and bought housing. We must not allow them to appeal the decision, so we must provide for this in the relevant laws.

In your opinion, should Qirim remain autonomous after de-occupation? What should be done with the peninsula after the return?

Autonomy is a way to organise life in a particular territory with certain peculiarities due to its history or the processes that took place there. Qirim is such a territory.

The Russian Empire colonised this land, and as a result, Qirim turned from a virtually mono-ethnic territory inhabited only by Qırımtatarlar into a territory with a predominantly Russian population. There were attempts to destroy the indigenous people in Qirim during the Holodomor; the people were deported for almost half a century, and everything reminiscent of the Qırımtatarlar was destroyed on the peninsula.

Preserving the Qırımtatarlar, of whom no more than 400,000 remain, requires unique governance mechanisms and special mechanisms for organising life on this territory. It is impossible to try to do this without a special status. Without unique means, it will be impossible to preserve the Qırımtatarlar or promote their prosperity.

For an original ethnic community, it is essential to have adequate representation in the government on their land. It is important because it is the beginning of any activity.

But how can effective representation of Qırımtatarlar be ensured when they are an absolute minority? Today, Ukraine has a single electoral code, a single rule for electing local governments, regional councils and the Verkhovna Rada. How can this electoral code be used to elect representatives of the Qırımtatarlar when ethnic Russians make up almost 60% of the population in Qirim, ethnic Ukrainians 25%, and Qırımtaris the rest? We need unique mechanisms.

There are situations where unitary states provide unique electoral mechanisms for certain territories to ensure representation. For example, in Italy, in South Tyrol, where Italians, Germans and the indigenous Ladin people live [there is a representative body — the provincial council, elected by proportional representation. The council consists of 35 members who elect the president of the province. Representatives of three linguistic groups should be represented in the provincial council: German, Italian and Ladin - ed.].

The second is the Krım-tatar dili. Yes, Ukrainian is the state language throughout Ukraine, and no one can deny that. But how can we preserve the Krım-tatar dili? Alongside the state language, we need to create opportunities to use the indigenous people's language. It is in Qirim because there is no other place where this language could be preserved and developed. Why not ensure that state and municipal institutions use the Krım-tatar dili alongside the state language?

The autonomous status of Qirim should, firstly, prevent the monopoly of any ethnic community in Qirim. Second, it should not allow for an ultimatum from any ethnic community. And third, this autonomy should strengthen the Ukrainianness of Qirim as much as possible.

The experience of 2014 should make us learn one lesson. The state must constantly patronise all its territories. Before 2014, the Ukrainian state had no policy towards Qirim, the Qırımtatarlar, or Qirim's autonomy. It left everything, as they say, at the discretion of the locals, and they had their interests.

Against the backdrop of the war, autonomy has become a toxic word. Many people perceive autonomy as separatism. However, it is not autonomy but its content that can promote separatism. The state sets the rules of the relationship between autonomy and the centre. The state is the administrator of this autonomy.

Therefore, mechanisms must be provided to prevent situations like those of 2014. Thus, autonomy is not an end but an instrument for the government to ensure its powers, including preserving and developing the Qırımtatarlar as an indigenous people of Ukraine.

No one outside Ukraine will take care of the Qırımtatarlar. They live within the borders of the Ukrainian state. In the same way, the state will take care of the preservation and development of the Ukrainian nation, it should also take care of the Qırımtatarlar, indigenous people.

Every nation has the right to self-determination, but this right is often a fearful one. The international community and law promote and support those forms of self-determination that do not violate existing state and interstate borders. When any people demonstrate and exercise their right to self-determination in a manner that does not violate state borders and territorial integrity.