Slovenija: Balkans or Central Europe?

"A small country, the most western in the Balkans. It is the home of the eccentric philosopher Slavoj Žižek and the wife of former US President Melania Trump" - this is how most stories about Slovenija begin. Even Yugoslav propaganda called it "the real gateway to Yugoslavia" when advertising this country to German-speaking tourists.

Republika Slovenija is tiny - 2.1 million people, or 70% of Kyiv, on the eve of the full-scale invasion. Nevertheless, Slovenija provided Ukraine with a relatively large amount of assistance. The value of the transferred weapons amounted to 0.10% of the country's gross domestic product. For comparison, Estonia is the absolute record holder in this regard (1.23%). In contrast, Canada, Italy, and France provided fewer weapons than Slovenija but allocated more financial assistance.

Despite this, we rarely talk about Slovenija. Although in the early twentieth century, Ukrainians and Slovenes lived in the same empire! Let's take a look at the history and current politics of Slovenija.

Limited dreams and parallels

Researchers at the Institute for Ethnic Studies in Slovenija's capital Ljubljana call the modern country "an important transit area in Europe". This trend has persisted for a long time, as ethnically Slovene territories were located simultaneously in the Italian, German, and Hungarian zones of influence. That is why there was a constant confrontation over them, even though the Slavs had lived there since the end of the sixth century.

Slovene historian Oto Luthar used an anecdote to demonstrate this trend:

In 2002, a large map was placed on a playground opposite a museum in London. It was supposed to tell children about the most famous cities in the world. The image of Venice completely covered the entire territory of Slovenija.

Ukrainians recognise this feeling. However, we are lucky because even if we draw a large Moscow, it will completely cover Ukraine. The emergence of the Ukrainian and Slovene states occurred only because these societies had an educated elite that contributed to the development of these cultures.

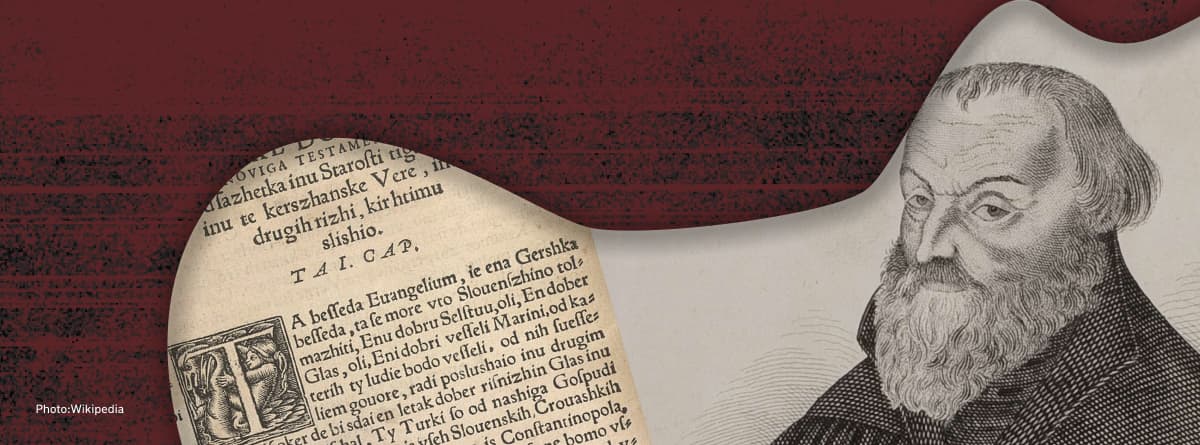

The nation-building processes in Ukraine and Slovenija took place almost simultaneously. For example, in 1550, the Protestant priest Primož Trubar created the first printed alphabet in the Slovene language so that Slovenes could speak and write in their own language.

Around the same time, Lavrentii Zyzanii was born, and in 1596 he published a textbook of the Church Slavonic language. This book is full of Old Ukrainian words of the time. He unlikely deliberately wanted to spread the Ukrainian language in print. Still, the results of Trubar's and Zyzanii's works are similar: the printed national language began to take root among the elite.

According to one version, Zyzanii was born in the Lviv region, in the medieval fortress city of Tustan. It dates back to Halytsko-Volynske kniazivstvo (the Galicia-Volhynia principality) but fell into decline as part of the Polish kingdom. At the end of the eighteenth century, the Polish state was destroyed by Prussia, the Russian and Austrian empires. All western Ukrainian territories were part of the latter. As a result, about two million Ukrainians and about a million Slovenes lived within the same empire.

However, at the end of the eighteenth century, Slovenija experienced an event unknown to the history of Ukraine — the Napoleonic occupation. The French army captured and retreated from Slovene territories several times. When France came to the Balkans for the third and last time, it incorporated the captured Austrian territories directly into its territory as autonomous Illyrian provinces, with the capital in Ljubljana.

France of the time was more similar to the modern idea of a state than any other country back then. The state not only took but also gave, including education. The French provincial administration introduced the native language of instruction in primary schools — Illyrian. Slovene intellectuals explained to the French that such a language did not exist. After that, in 1810-1813, the Slovene language was taught in the provinces' schools.

Although this policy was another step towards Slovene nation-building, most provincial residents viewed the French negatively. They were seen as foreigners who levied too many taxes. The Slovene historian Peter Vodopivec writes that folk artists depicted the following scene: a French soldier, tired of food and drink, lies down in a peasant cradle, and a peasant cradles him and turns him from side to side.

In the end, pro-French views were marginal even among the educated elite. It is noteworthy that the situation in Ukraine was similar. On the eve of Napoleon's French campaign against the Russian Empire, Polish General Michał Sokolnicki suggested creating French-controlled principalities in Chernihiv and Poltava. Napoleon read these proposals but could not implement them, even in theory, because the French army did not cross Ukrainian territory on its way to Moscow.

Despite this, the attitude in Ukraine towards the French was highly negative. The elite strata of Ukrainian society saw Napoleon as the child of the French Revolution, who had destroyed the aristocratic class of France. Similarly, the wider public mostly did not think in strategic and national terms but was guided by their socio-economic interests. When the descendants of the Cossack community joined the volunteer regiments to fight against Napoleon, they hoped to earn the tsar's "mercy" — liberation from serfdom.

During the nineteenth century, nation-building processes on the Ukrainian and Slovene territories in the Habsburg Empire took place concurrently, although the Slovenes had the upper hand. For example, since 1851, Mohorjeva družba (St. Mohor's Society) operated in Slovenija, promoting the Slovene language among illiterate people. A functional analogue in the Ukrainian territories was the reading room of the Prosvita Society, founded in 1868. In 1864, Slovenija established Slovenska Matica (the Slovene Society), which published scientific literature in Slovene. The Halytsko-Ruska Matytsia had existed since 1848.

However, according to Oleksandr Sedliar, PhD in History, by the 1860s, Matytsia was inactive enough and became a religious rather than a national publication. Moreover, its leadership included Muscophiles. Therefore, in 1868, its place was taken by the Shevchenko Scientific Society. Both the Shevchenko Scientific Society and Slovenska Matica still exist today. In addition, in Slovenija and Halychyna, there were Sokil sports societies aimed at the physical education of young people and national awareness.

Ultimately, the strategic objectives of the national movements of the two nations were similar. The Slovenes wanted a "united Slovenija", i.e., including all ethnically Slovene territories in one administrative entity within Austria-Hungary. This would have been more difficult to achieve in the Ukrainian case, as most Ukrainians lived in the Russian Empire. Nevertheless, Ukrainians on both sides of the border practised, as Mykhailo Hrushevskyi wrote, "measures for rapprochement". For example, people from Halychyna and Bukovyna would visit Taras Shevchenko's grave and leave notes in the book of impressions emphasising their national and regional identity.

Neither Slovenes nor Ukrainians, for the most part, sought independence in the early twentieth century.

An era of violence and different socialism

After the outbreak of World War I, the directions of these nation-building movements diverged, although both peoples fought together in the Austro-Hungarian army. Moreover, Ukrainians defended Slovenija's territories in the battles against the Italian army near the Soča River.

However, the size of the two nations was crucial. The Slovene elite could not imagine how a country could be created from such a few people. Ukrainians, on the other hand, although initially doubting the feasibility of their independence plans, were eventually forced to go along with it. On the other hand, the Slovenes hoped to unite in one state with other South Slavic peoples. For this reason, Slovenes who Russia took prisoner of war took Serbian citizenship and joined the Serbian army.

The defeat in the war finally destroyed Austria-Hungary. The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes emerged on its southern territory, as the supporters of the Yugoslav movement wanted. Instead, Italy did not receive what it had been promised by the Entente for its participation in the war — a part of the Habsburg territories, including those with a Slovene population.

In his poem, the military pilot and harbinger of Italian fascism Gabriele d'Annunzio called this outcome of the war a "mutilated victory" and called for not allowing "wings to be clipped". This image mobilised war veterans who wanted revenge. Ultimately, it led to the emergence of Italian fascism and the desire to assimilate those Slovenes living in Italy. This shaped the negative attitude of Slovene intellectuals towards fascism.

The situation with Ukrainian nationalists is different. According to the historian Oleksandr Zaitsev, they did not try to copy fascism, yet in the 1930s, their attitude to Italian ideology was somewhat favourable. An organisation of Ukrainian nationalists even planned to translate the texts of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini but did not have the money.

In April 1941, the Germans and Italians occupied the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the successor to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. This and the interwar experience of assimilation in Italy determined the future vector of the Slovene national movement. Communists and liberals united in one guerrilla front. Conservative Slovenes still tried to cooperate with the occupation regime, so there was a struggle between them and the partisans.

For example, in 1942, partisans killed a Catholic priest, Lambert Ehrlich, who supported the occupation forces. Eventually, the partisans liberated Slovenija and the whole of Yugoslavia. Although the partisan army consisted of people of different beliefs, it was the Communists who played a crucial role in the leadership. After the war, they killed approximately 11,000 Slovenes who were members of pro-occupation armed groups. Ukrainian history developed similarly.

Communists came to power in Yugoslavia. Although the Yugoslav regime was authoritarian, it was not as closed as the Soviet one. For example, since 1968, the University of Ljubljana has conducted public opinion polls. At that time, the leadership of Soviet Ukraine learned about the mood of the population only from reports of local party branches and KGB offices. The USSR only made such an "invention" as representative polls in the late 1980s.

Research by the Public Opinion Centre of the University of Ljubljana makes it easy to establish that Slovenes mostly saw themselves as part of Europe. In 1970, no respondent desired to go as a labour migrant to the USSR. At the same time, most of the population justified the need to spend large sums of money on road construction because Slovenija needed to be better connected to Europe. And on the eve of the collapse of Yugoslavia, 65% of Slovenes favoured building a state similar to Western European countries.

It is, therefore, not surprising that Slovenija was the first country to secede from Yugoslavia. This happened, just like in Ukraine, without a full-scale war. Serbian communists became more nationalistic, and the opposition in Slovenija became more influential. In 1990, Slovene communists decided to hold democratic elections, which were won by a democratic coalition. The new government announced an independence referendum. 88% of Slovenija's population voted in favour of independence.

At the same time, Slovenija's leadership still hoped to maintain good relations with other Yugoslav countries, writes political scientist Sabrina Ramet. Therefore, the Slovenes proposed to turn Yugoslavia into a confederation. Serbia and Montenegro rejected their idea, so Slovenija declared independence on June 25, 1991.

Yugoslavia tried to stop this by sending an army into Slovenija, but within ten days, the European Community persuaded the parties not to proceed. The army withdrew, and Slovenija had to suspend its independence for three months.

In 2004, Slovenija became a member of the EU and NATO. This was due to the country's small size. In the case of the EU, only 10% of the population was employed in agriculture at the time also played an important role. In Ukraine, this figure has been no lower than 15%.

The failed authoritarianism of a former dissident

Former dissident Janez Janša was elected Prime Minister three times. Over the past 30 years, his rhetoric has become extremely demagogic. He has simultaneously fought against the "post-communist mafia", the Yugoslav past, the Americanisation of Slovene culture and George Soros.

Although in 2014, Janša served six months in prison on corruption charges, this did not prevent him from winning the Prime Minister's post again in 2020. The victory resulted from Janša's repeating the electoral strategy of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban and even receiving media support from his allies.

This did not stop Janša from siding with Ukraine. He was among the first to visit Kyiv in March 2022 and compared the full-scale invasion to Yugoslavia's war against Slovenija. Moreover, he tried to portray his election rivals as Putin's allies.

This did not work. In the April 2022 elections, his Slovene Democratic Party was defeated. The new government consists of the Greens, Social Democrats and the Left. They are the ones who gave Ukraine the M-55S tanks.

Trade paradoxes and lessons learned

In 2022, another unusual event took place in Slovenija. The volume of its trade with Russia increased by 2.5 times. Those concerned sent an inquiry to the Slovene embassy in Russia to find out how this could happen when Russia was under sanctions, and most other countries traded less with the Kremlin.

Deputy Ambassador Bernard Srainer replied that Slovenia was aware of the problem. He was developing a report on this topic and concluded that physically, there were fewer exports and imports. Still, due to the jump in prices for goods, as well as for transportation and insurance, the amount of money was higher than the previous results.

The real volume of imports of fossil fuels and petroleum products fell by 50% compared to 2021,

the diplomat says, adding that the country is complying with all sanctions packages.

Let's look at the statistics. Indeed, imports from the Russian Federation, expressed in kilograms, were lower in 2022 than in 2019 but higher than in the pandemic years of 2020-2021. Exports of Slovenija’s goods also fell by 10%. The average annual weight of shipments over the past 20 years has been about 95,000 tonnes; in 2022, it was 10% less.

Therefore, Srainer is right, but we will see what the results for 2023 will be. Even the most successful history of post-communist integration can be levelled out by maintaining economic relations with Russia.

At the same time, Slovenija remains an interesting example of European integration for Ukraine. It is impossible to copy it due to the difference in socioeconomic characteristics, but this will not prevent us from learning lessons.