On Wounds, Corruption and Civilians: An Interview with US Army Veteran Dennis «DJ» Skelton

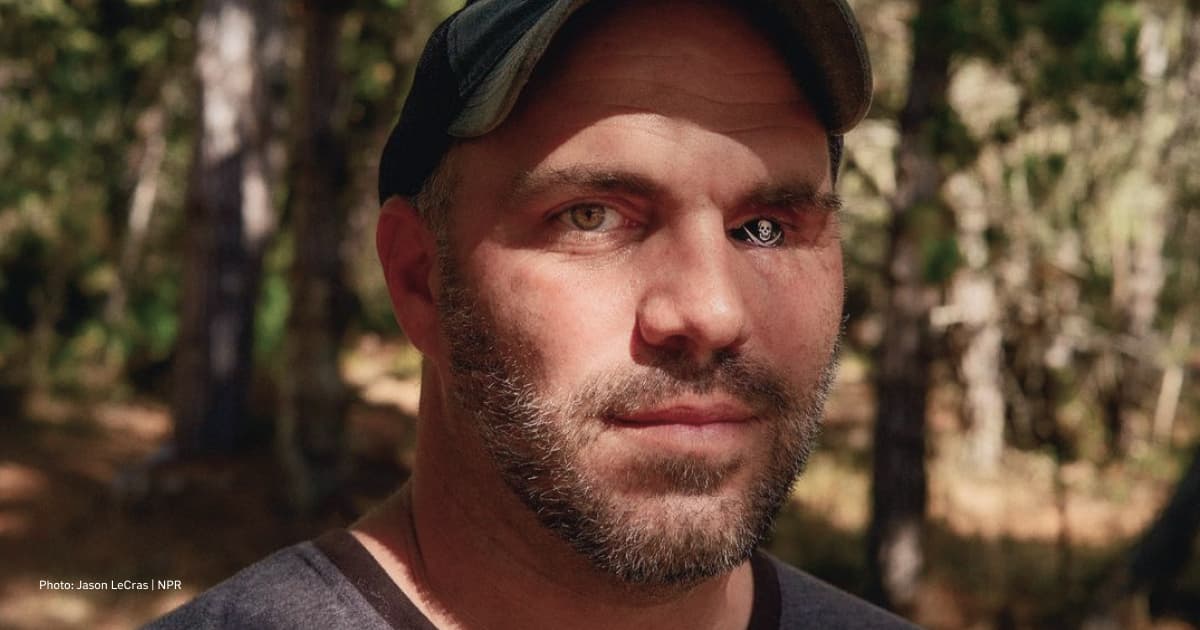

Dennis «DJ» Skelton is, perhaps, a great metaphor of a veteran. Observing him from a distance, there is little remarkable you could possibly take notice of. He could be a physics professor, a US businessman working out his options in Ukraine, or a head of regional administration. But take a closer look, talk to him, and you can learn a lot about him, veteran issues and life in general.

DJ was raised in a rural community in South Dakota (a state, he tells us, not many US citizens can find on the map). He enlisted in the US Army in 1996. Thanks to the assistance of his superiors, DJ was able to get into West Point Military Academy. Having graduated from it, he led a rifle infantry platoon, which was deployed to the front lines of the Iraq War.

November 2004 has changed his life forever. While in combat, he was wounded severely. A shrapnel entered his head through the left cheek and exited through the right eye, damaging everything in between, including the palate. This trauma severely complicated his ability to eat. But that’s not all. His right hand was also wounded, as well as his arm and chest.

When DJ was flown back to the US, his country had little recent experience in dealing with many wounded veterans. Therefore, for the past 20 years, he has spent much effort in the military, government and non-governmental sectors to change the ways these communities perceive DJ and people like him. He was pretty successful in his mission, and his biography clearly indicates this. Despite his wounds, DJ was allowed to serve in a combat position in Afghanistan.

His mission of helping the veterans (as he says, those on the right side of history) brought him to Ukraine. DJ has helped establish the American-Ukrainian Veteran Bridge. It is an organization working with the Veteran Fund to help Ukrainians on their way back from the military to civilian life. That is why Svidomi was able to talk to him.

First time in Ukraine, right?

Yes.

But you traveled a lot, didn't you? Iraq, Afghanistan, and China (DJ spent a year in China as a foreign area officer for the US military – Svidomi). What else?

– I have also been to Japan. There are lots of opportunities within the military.

But I assume in none of these countries, you have seen so many veterans as in Ukraine.

This is the first time that I have been abroad on a non-governmental mission. This is the first time that I’ve been here, specifically to find veterans. And therefore, I see more of them here, especially at this moment in history.

How does it feel to be around people like you in many ways?

It's humbling but sombre. I can empathise with the feeling of facing the enemy. And then to doubt whether this is the last chapter of your life. Whether you will survive it. You're in that moment, and then you come home. You experience all these feelings, emotions, fear, stress, anxiety, and depression. So when I look around, I think: "Oh, there are a lot of people here; there will be many of us".

However, it’s also a beautiful thing. For me, one of the greatest fears in life is getting settled where we are. Our brain stops being curious, and so do our hearts. We just wake up. Go through the day, go to bed, and we would repeat it over and over.

Everyone gets to look in a mirror and ask themselves if they want to innovate their life. And then go back to a chalkboard and say, okay, I have just done this new thing and learned a lot about myself; I have also learned a lot about things I hadn’t expected to know. Where do I want to go with that in life? That can be very exciting if the right resources are in the right community. That is part of the integration back into society. Otherwise, we come home and go back to what we used to do if we can do that.

That’s when it becomes kind of dangerous, and we almost forget about war. And we just go back to our daily life. But one can’t forget about war. There are things I've learned during the war I never would have learned about myself that will make me a stronger, more successful person.

I have seen in the media that you have been called the "most wounded commander" in the US Army. Is this true? It makes little sense to me because it is impossible to tell who is more or less wounded.

But it is pretty obnoxious. At the same time, if your son or daughter is going to war and their life is in their commander's hands, do you want your commander to be 50% fit? 75%? You're looking at me. I'm not 100% physically, and I'm not 100% mentally healthy.

However, I still wanted to return to my position and finish my job. It didn't matter to me where my soldiers were; they just happened to be in combat. So, I created a path to get back.

So this is what happened in Afghanistan: you came there, and you felt that you did not perform up to your standard, right?

Correct. But does that mean that there is no place in the military for people who have disabilities, who have limitations, who are not achieving 100% of what their peers are capable of? No. The military has almost every job society has. We have janitors, right? So for a military to say, oh, you are wounded, you are of no value to us, go home – now that’s interesting. When I'm most vulnerable trying to figure out my worth, that's an interesting thing to say to me, right? I think there's this culture that we can create that allows wounded people to go to the training, go to school, and then build stuff from there. You can still stay and contribute to the military, but maybe not in certain positions.

This culture did not exist in the US military at the beginning of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. And I was wounded at the beginning. It took a while. We had to write new policies. We had to change the way the government authorized the military. We had to change and educate a lot of military leaders. You need compassionate leaders willing to assume a little risk, believe in their people and allow them to go and do their job. It took a while for us in the US to realize.

When I look back, even in the last ten years, we have soldiers who are blind but still in uniform and teaching. We had a blind officer commanding a unit – for the first time in history. It wasn't overseas. It wasn't in combat but a critical unit that needed a good leader.

In the past, there were few examples of wounded people serving in leadership positions. Nowadays, I've lost count. I mean, there are probably hundreds of wounded service members that have stayed in the military. And it's made for a better military. It's made for a more diverse military. It's made for better soldiers.

Imagine getting wounded, coming back and getting put back together while having the support of the government, the medical system, and society. Imagine a scenario with flaws but good enough to keep me in uniform and moving forward in my career. That’s the military I want to serve in.

If you are a young private, that’s 18 years old, straight out of school, and that’s your instructor (DJ points at himself – Svidomi) – that’s pretty powerful. It can be.

Sure, if the person is open-minded.

Exactly. There’s another scenario. A system from which you are kicked out as soon as you are wounded. And then you have to figure it out all on your own, fighting for health care and what you see as basic rights. Am I here to go to work? 100%. But am I motivated? Of course not. Both the morale and capabilities of this unit are declining because people are becoming less and less motivated.

I have a question about your ocular prosthesis. In your pictures, I saw that you had a different prosthesis that looked like your real eye. Now, you have a prosthesis with a Jolly Roger pirate flag drawn on it. What made you change the former for the latter?

When I first started wearing a prosthetic eye, it was always a prosthetic that looked exactly like the other eye. It's a "let's make you look like you were before you were injured" concept. The problem then was that both eyes were not horizontally aligned. And I have all these scars near my eyes. So when people looked at me, they thought that the eye looked fine, but the rest of me didn't. Their brains were confused. So they would stare even more and more, just trying to figure out what was wrong with my face. It was awkward.

So, almost from the beginning, I had this thought that I didn't want it to be like that for the rest of my life. If you're going to stare at me, let me give you something more artistic that might lift your spirits. Let me give you an icebreaker (Dennis "DJ" Skelton has a prosthetic with a Jolly Roger pirate flag). Because I enjoy people asking: How did that happen? Because I am very proud of the chapter of my life when I chose to volunteer to serve my nation, and it resulted in what it did.

But that’s life. We all make choices, and those choices have consequences. We're just trying to get through this thing called life, aren’t we? And have fun on the way. So, I have a lot of different prosthetic eyes. Maybe 12 or 15. Different types.

How does the process of manufacturing one go?

It is made of glass. You make a mold of the shape of your eye. Once you have it, they pour glass into it, bake it, and then an artist would take a palette of colors and paint whatever you want.

And are these artistic works paid for by the government?

Yeah. You make an eye anyway. Let’s say it takes seven hours to make an eye. It takes seven hours and fifteen minutes to draw something on it. But if you want to draw something identical to your other eye, it would take hours. So doctors love it when I tell them that I want something artistic.

And what other drawings do you have?

I have a typical Purple Heart (military decorations in the US military, awarded to those wounded while serving – Svidomi), a US Army symbol, a betta fish. My son is really into Paw Patrol, so I now have one of the shields from the dogs.

Do you still need to get through surgeries?

The eye itself has weight to it. Gravity is our enemy. My eye was an exit hole, not an entry wound. The eye socket that holds the eye is made of parts. So, every three to four years, the weight of the eye will sink the socket. Looking at me, you will see it’s starting to drop. I probably have another year, and then I will go for surgery, change it, and repeat it for the rest of my life.

Are there long queues for the surgery? How long do you have to wait to get one?

Sometimes it is better, sometimes it is worse. There are plenty of stories about this. The queues were six months or even a year. Imagine I need to see a counselor; I need to see a therapist. I am struggling. I need help. The veterans are figuring out some of that and can ask for help. The answer was: Okay, come into the office, here is your appointment, come back in nine months. But I am telling you: I need help right now.

So there have been some laws that said if the wait time is longer than this amount of time, you can go to a private company, and the government will pay it. There were some limitations, but the point was that if you can get care quicker outside the government, do that.

Does this work? We are still learning. Sometimes it does, sometimes it does not.

And it has been 20 years…

It's been 20 years; that system was not there initially. During the war, we learned that queues happen because the rate of people who come and need help was higher than the rate of health workers hired and trained by the government.

Soldiers are coming back – that's going to be a problem, and that is a problem for all governments at war. Now, it’s a problem for the Ukrainian government.

Because of the USA's resources, we could try different things even during the war. But how do you know if the policy is failing? Well, who's the one person that knows this better than anyone else? The veteran. So, how does the government know that veterans do not get what they need?

That’s an interesting problem. Have we created the microphones? Have we made the platform so that veterans can express their frustrations in a way that articulates and describes precisely their needs and how they're not getting what they need?

That’s hard communication. You are communicating between the groups that do not really know each other. You get a lot lost in the translation. The Veteran’s world is highly emotional. But if you go to a political meeting, where they are writing laws – that’s a pretty dull world that lacks emotion sometimes. As a politician, I don’t want to sit and talk to somebody yelling and screaming at me. But at the same time, if we don't figure out how to help those two groups communicate, we'll never figure out the problem and the solution.

The relationships between the politician and the soldier between the businessman and the warrior, have a difficult history. It wasn't that long ago that I would apply for a job, and they would not even hire me, only because I was deployed to war because you thought everyone who goes to war is messed up mentally. Well, that’s silly, but who’s educating the CEOs?

It took a long time to change the culture so that when the soldiers are coming back home from the frontline, they are not judged based on the decisions they made in their lives. We are dealing with a societal problem: You do not judge a person based on one decision without getting to them, be it a veteran or LGBTQ.

I read your open letter, published in Foreign Policy magazine. The government has told you to change the liquid you use for the feeding tube (DJ uses a feeding tube to receive energy because part of his mouth is wounded, which complicates the consumption of food – «Svidomi»), and later wrote they are not able to pay for the liquid they recommended. That’s a paradox. Encounters with public services often produce paradoxes in Ukraine, too. What other paradoxes have you encountered over our journey?

After 20 years in therapy, I have understood and love this beauty of contradiction nested in the «fight for freedom» concept. If you are really fighting for freedom, risking everything you have when going to the frontline, then you're also fighting for the freedom of your fellow Ukrainians to choose not to do that. That’s the paradox of freedom and democracy.

I want to say whatever I want, but I don't want you to say these things about me. How do we coexist? That’s hard, extremely hard for warriors to separate these two things. If what we are sacrificing for is our home front, then there is this natural feeling that everyone should contribute.

Now I'll be extremely clear – there is no place for corruption, assholes manipulating the system for personal gains.

But there's this group of citizens that are good people; they just don't want to fight. You can contribute other ways to make your country strong, especially during the war. We just talked about Ukraine having a lack of healthcare professionals. Right now, you are struggling. Serve your country and study medicine or psychology. Or be a businessman or a businesswoman, get a building ready for a factory so that when veterans come from the frontline, you can hire them and help rebuild your country at any rate. You have a lot of teachers from 18 to 55 on the frontline. Be a teacher and fill the schools with really good educators to take care of the next generation. To me, that’s serving your country.

And again, it took me a long time to think about this. But I absolutely believe that this is the state of the country that I would be very proud of.

How Ukrainians were reacting to your eye?

Soldiers liked this – it is fun to have a pirate eye. Some people with whom I was in the queue in the bar said that the eye was cool, but none of that led to curious conversations.

There is also a related ongoing conversation in Ukrainian society. How much attention should you pay to a veteran in a public space without violating their privacy? For instance, my friend was standing in a queue with a veteran at the end of it. So she asked him multiple times if he wanted to take her place or if she could buy him anything, but he refused.

When I was younger and single if I was standing in a line and a lovely young lady came up, I would ask her to stay in front of me. It is all personal interest. And if a person wants to pass their place in the queue or pay for the veteran in a restaurant – that’s probably because this person needs to do that. Not because I care about them, but because I would feel happy by doing this. It’s probably selfish.

But again, every veteran is different. People often like to take this peanut butter spread, and just like – they are all the same. Some veterans might want that. Some veterans feel entitled. I served there, therefore I should get this. Really? I have a problem with entitlement; we are just people, nobody deserves anything. We are just trying to get through this life.

There is no way I will spend 12 years in college to be a doctor. No way. So, should the doctors now serve in the frontline? Firefighters, police. Being a policeman in some US cities right now is not the happiest career. Should they move to the frontline?

It takes a mature society to look at each other and see how interdependent we are. I will not wake up at 2 AM and spend 12 hours pouring concrete so you can have a nice, smooth ride. I am not doing this, and I live in a country where I can choose not to. So, should the construction workers now go to the frontline? We all depend on each other. You depend on the soldiers to go to the frontline, but they depend on you to give them a voice, to be heard. Most of the time, this relationship is not direct.

I think it is the healthiest way to transition for the soldiers: to spend some time thinking about how they played a role in making Ukraine strong and how all the other people who do not wear uniforms played a role in making Ukraine strong.

In America, we had this yellow ribbon. People wore it to show their support for the troops. Magnets on a car, stickers, all over the place. It's now a complete joke to the military community. We have homeless veterans, we have veterans’ suicides, we are struggling, we can’t get health care in a way that is fast and efficient, we can’t get jobs. You put a yellow ribbon sticker on your car, and then – done. Initially, it was different; it symbolized national pride, and troops loved this. But it was words, not actions.

But I think there are ways to tell the story. If only there were smart, passionate journalists who wanted to sit down and talk to veterans. Help them put the words together and tell their story. It is a win-win situation: you help veterans but also help citizens who are not serving understand the existing problems and what resources are needed. Because citizens have these resources: their brains, mouths, and pens. With these you can bridge the gap. Everyone plays a role, but corruption and entitlement have no place.

After a long conversation, DJ proceeds to his hotel room. He needs to change – formal attire is required by the next event scheduled. I am left thinking of what I have just heard. These are undoubtedly unorthodox ideas. But to what degree can they be applied to Ukraine, given the stark differences between the wars and the societies?

- DJ participated in a counterinsurgency overseas. Ukraine, instead, is fighting a war of survival against a bigger enemy equipped with almost every weapon you can think of.

- The American society is primarily liberal, meaning individualistic. The Ukrainian society is mostly collectivistic, not least because the Communist party systemically attempted to limit the time an individual spent outside groups.

- DJ emphasizes that he spent 20 years in therapy and was involved in veteran affairs. Ukraine is not 20 years away from war.

To learn is not to simulate what someone else did but to see how you can accomplish your goals with the tools you get from others. Thus, DJ is a great source and inspiration to look up to, but we have to figure out our own ways.