Kakhovka Reservoir and Zaporizhzhia: What is happening after the explosion of the dam

The explosion of the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant caused at least two problems at the same time: the areas below the dam were flooded, while the water level to the north of the plant dropped significantly. The large reservoir that was held back by the dam turned into a series of lakes that dry up in the sun.

Residents of coastal settlements have no water for irrigation, and the banks of the Dnipro and the reservoir are covered with dried mollusks, algae, and dead fish in some places.

In this report, we show what the Kakhovka Reservoir and the beaches of Zaporizhzhia look like and how this has affected nature and the locals.

The village's outermost street offers an eerie view of what remains of the Kakhovka Reservoir. Instead of a continuous stream pool, there is a dry plain with water residues in the hollows. The naked eye can see small lakes evaporating under the scorching sun.

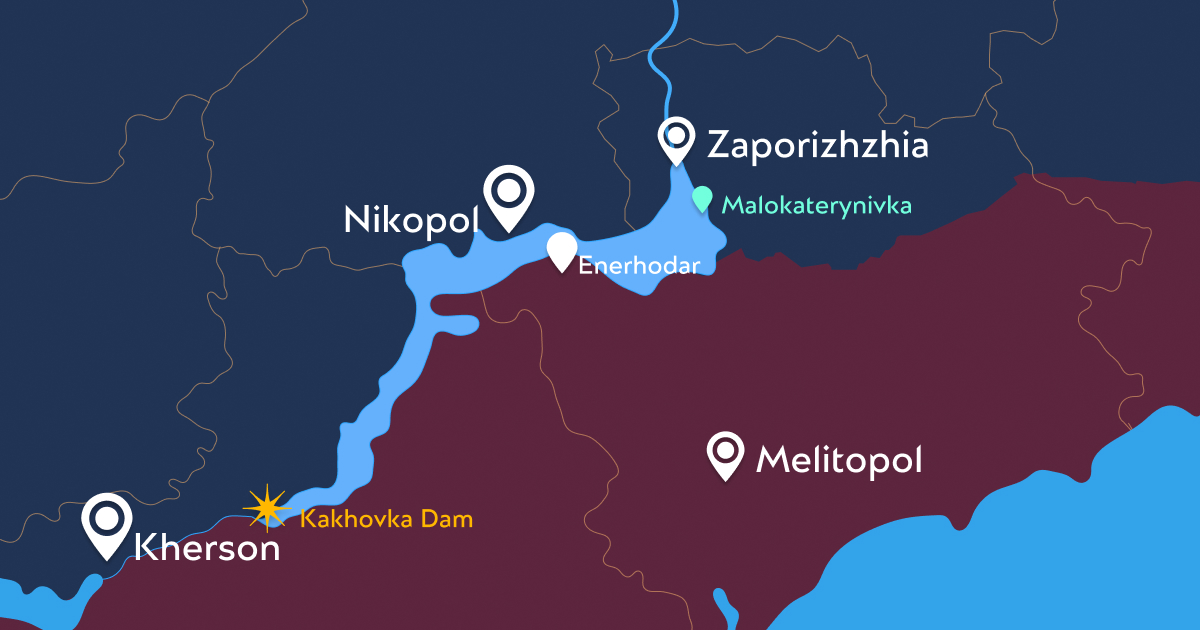

A distant explosion is heard. A few minutes later, a column of smoke rises in the direction of the temporarily occupied territories. It is about 15 kilometres in a straight line across the reservoir to the contact line in Kamianske. In recent weeks, active fighting has been going on in the Zaporizhzhia direction, with the sounds of it occasionally reaching Malokaterynivka, a village that is washed on one side by the left tributary of the Dnipro, the Konka River, and on the other by the Kakhovka Reservoir.

To get to the reservoir, you need to make your way through the bushes to the railway tracks that run along the reservoir's shore from Zaporizhzhia to Vasylivka and then through Melitopol to the Crimea. After the tracks, there are overgrown bushes and a pile of large stones. Before the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant was blown up, the water level almost reached the railway.

As soon as I reach the shore, I see a father, his son, and his daughter on bicycles. The boy calls out to me to look at their discovery and enthusiastically tells me what his father said about the World War II shell, although he doesn't understand when it happened or how it differs from what is happening 20 kilometres away.

The family lives in Malokaterynivka. They come to the reservoir to see how the water level has dropped and what interesting things are left on the ground. The father says they have already found up to ten pieces of different ammunition. They order bottled drinking water, but there is not enough for irrigation — it used to come from the reservoir.

Closer to the water, the soil is marshy, mouldy, and has a strong odour. As soon as I get closer, my feet get stuck in the mud, and dozens of insects instantly swarm around them.

There is rubbish on the bushes and between the stones that used to float in the water. Most of the shore is covered with small grey stones. As I get closer, I notice that these are shells and mollusks that have been stranded on land and died. Now their shells are cracking underfoot.

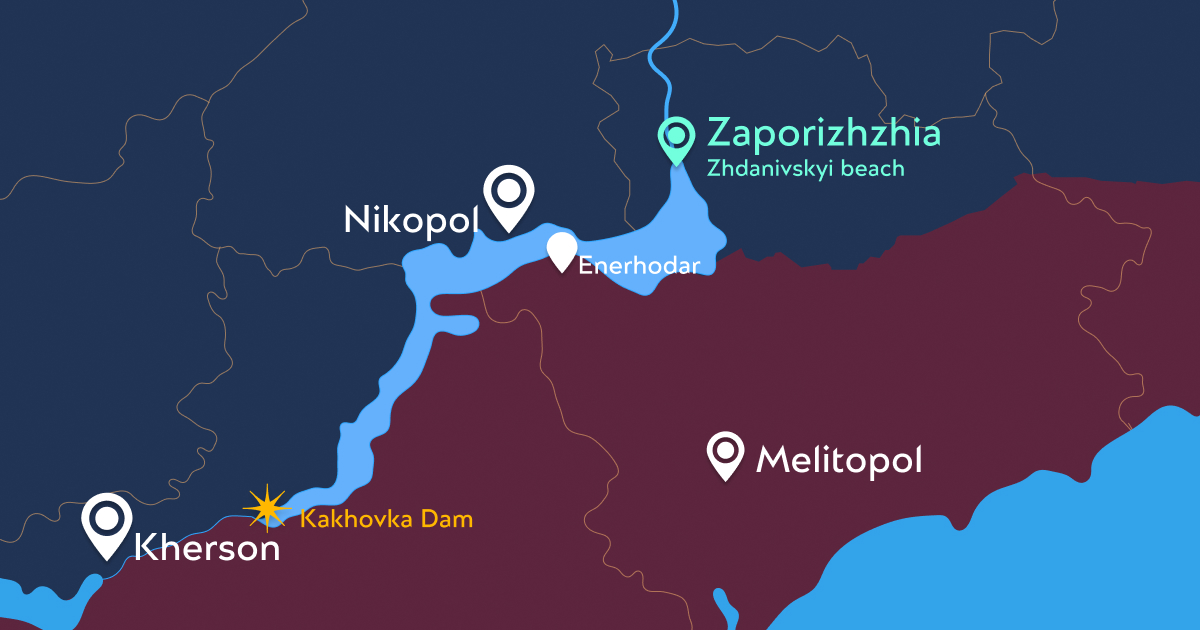

It's Friday, ten in the morning. Several people are sunbathing on the beach, and some are swimming. There is fresh, damp ground near the river — the water level is still gradually decreasing. The silt has aquatic plants in it, which will dry up on land in a few days.

A man with a metal detector and a shovel walks by the water. His name is Arsen. His naked torso is covered with tattoos, his feet are bare, and his trousers are rolled up to wade into the water. He says that everything that could be valuable in the river was found in the first days.

The locals say that after the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant was blown up, the shallowing of the Dnipro was visible on the same day, and the water receded by two to three metres every day.

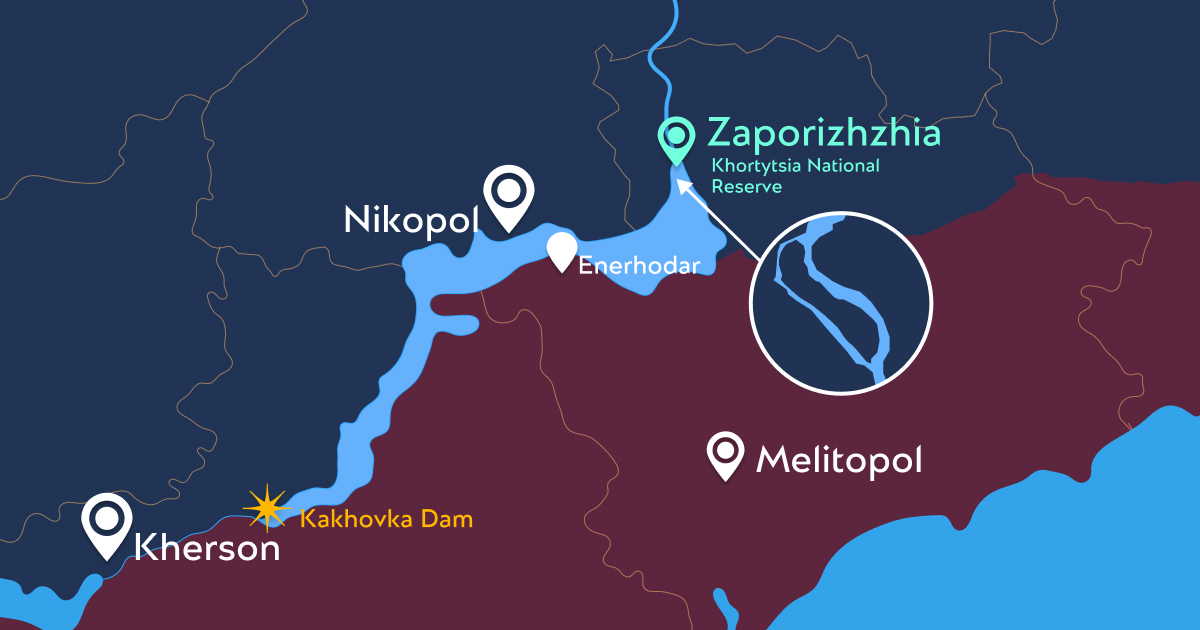

"Look, there is a yellow rescue booth. Before the dam was destroyed, there were three more metres of water from the booth. It was standing in the water, and the rescuers were tying the boat to the poles. And now look, you can even walk to Khortytsia," says Arsen.

Khortytsia is the largest island on the Dnipro River and one of the Seven Wonders of Ukraine. The island is best known for being home to the Cossacks from the 15th century until the liquidation of the Zaporozhian Sich in 1775. To the north of the island were the rapids, after which Zaporizhzhia is named.

After the HPP was blown up, the water level near the island dropped, islands and stones appeared, and you can partially see what the rapids used to be like. The main part of them is located north of the Dnipro hydroelectric power plant and still remains underwater.

When the Kakhovka Reservoir was filled, a complex of permanent lakes was formed on Khortytsia. Mykhailo Mulenko, the acting head of the nature conservation sector of the Khortytsia National Reserve, says that after the hydroelectric power plant was blown up, the water escaped from the reservoirs due to the shallow bottom. There are almost no lakes left on Khortytsia. All the aquatic vegetation died because it ended up on dry land. The fish managed to swim away, but other aquatic life, such as mollusks, remained at the bottom and died.

There are no problems with water supply in Zaporizhzhia, as the city is supplied with water from the Dnipro HPP, but the city authorities say they are paying extra attention to the possible fish pestilence. Representatives of district administrations, municipal services, and the Khortytsia Nature Reserve have developed an action plan. Mykhailo Mulenko says they are considering the option of reclamation fishing — the removal of certain species of aquatic life to improve the ecosystem.

"The methods of fishing depend on the situation: somewhere on the bottom of a snag, nets can be thrown. Where the bottom is flat, you can use nets or cast nets. This fish will be caught as long as it is alive and has no signs of poisoning. And then, we will collectively decide what to do with it. Perhaps send it for processing and canning," the scientist says.

The island is located on a transnational bird migration corridor. From Khortytsia, you can see how the birds have settled on the island, which used to protrude from the water only at the top. Rare species, such as the Canadian goose or geese flying from Finland, come to the rocks to spend the winter. The water does not freeze here, the hydroelectric power plant works, there is always fish, and birds have something to eat.

Mulenko says that now this area is completely useless for birds because there is no water. The birds can fly away, but there were nestlings and eggs which will die in the nests. In the future, the area will be unattractive for migratory birds. Upstream of the Dnipro hydroelectric power plant, there is Sahaidachnyi Island, where conditions will be no worse because the water level has not dropped.

"Did you see two planes today? We were sitting near the water, and when they flew over us, we had to cover our ears. I said, 'Oh, my God, my boys, please come back. But they flew by, dropped what they needed somewhere, and came back. Immediately, smoke went up on the other side [the temporarily occupied territories]," says a local woman. She introduced herself as Valentyna Pavlivna and was on her way home from fishing.

The woman looks about 50 years old. She is wearing a plaid shirt and a scarf with flowers. She carries a bag of fish on her shoulder and complains that there are fewer fish in the Dnipro, and that the fish that has not moved away with the river will die in the floodplains. In the village of Lysohirka, which is located downstream of the Dnipro, almost 2,300 kg of aquatic life has already died.

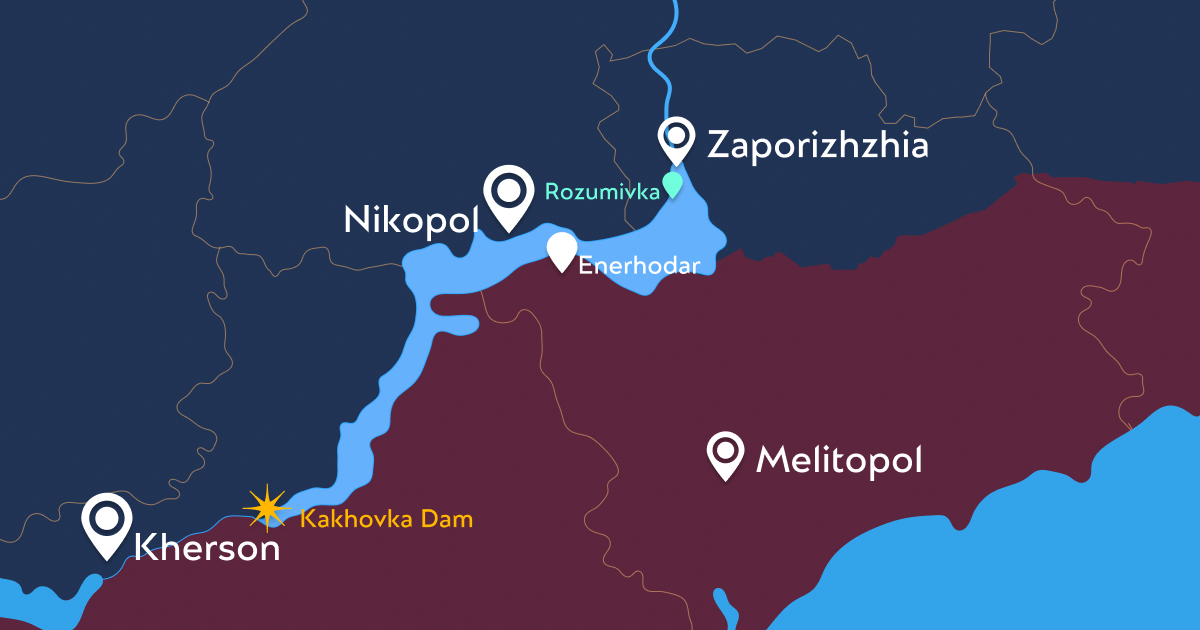

The village of Rozumivka is a 30-minute drive from Zaporizhzhia on the right bank of the Dnipro. The outermost street ends in a floodplain, which has already become significantly shallower, and in some places is almost completely dry. A viscous swamp has formed on the banks, and the water becomes mouldy.

The scorching June sun further dries up the local ponds and gardens. To keep the crops alive, they are constantly watered from the centralised water supply system. There is no water left in the wells and boreholes, or it is very shallow.

"So many crops were ruined. I pulled out the cabbage yesterday because there is nothing to water it with. Cabbage loves water. Half the yard is empty because there is simply not enough water for irrigation. Only if it rains will it save us," says Valentyna Pavlivna.

Beyond the floodplain, there is a forest, and beyond it, access to the Dnipro. It was here, near Rozumivka, that a barge carrying crushed stone ran aground and sank in December 2020. After the river's shallowing, a large part of the vessel was above water. People from Zaporizhzhia come to take pictures, but the barge is already being sawn up by its owner's representatives.

The Dnipro bank is covered with soft and warm sand. The only evidence that the water level used to be higher is half-dried algae, layered sections of the beach, and dead fish and shellfish.

Since the area of the shore has increased significantly, locals come to relax — sunbathing, picnicking, walking, watching the Dnipro shoal up, and seeing what else it has left on the shore.

What's next?

"The water has receded from the banks by 1300-1600 metres. The Dnipro is practically returning to its course as it was 70 years ago," wrote Interior Minister Ihor Klymenko.

70 years ago, the Kakhovka HPP had not yet been built, and a reservoir had not yet been created. In its place was Velykyi Luh, a territory with river floodplains on the left bank of the Dnipro River that belonged to the Zaporizhzhian Sich. Here, the Cossacks planted artificial forests and defended themselves against nomadic Tatars who were not used to wet marshlands.

During the construction of the hydroelectric power plant, in 1955-1957, Vekykyi Luh was flooded. Its flora and fauna, as well as historical artefacts from the Cossack era, ended up at the bottom of the Kakhovka Reservoir.

"The entire Dnipro bottomland, from Zaporizhzhia to Kakhovka, immediately became unrecognisable. The large Zaporizhzhia Luh was submerged under the Dnipro water, and the old crosses in the grandfathers' cemeteries were drowned forever. Everything that had seemed beautiful to fathers and grandfathers for centuries from their early childhood years has disappeared," Oleksandr Dovzhenko wrote about the creation of the reservoir in his Poem Of The Sea.

In the village of Pokrovske, near Nikopol, the remains of the Cossack Sich Church of the Intercession of the Theotokos were found after the reservoir was shallowed. The director of the local museum, Larysa Sadovska, told Nikopolnews that in 1734-1775, the village was the site of the New Sich. The Sich was destroyed by the order of Catherine II, and the church was damaged and looted by noblemen, soldiers, and Don Cossacks. In 1798, a new stone church was built in its place, which lasted until the flooding of the Luh.

On the dried-up bank of the reservoir, I see a man with a metal detector. Before I can approach him, he hides behind the bushes with a sack. There are fresh traces of excavation on the ground. After about 10 minutes, the man comes out again — this time without tools. He says he only comes across tin cans, old dishes, or other junk. He does not allow photographs of himself because he "works at a critical infrastructure enterprise."

The Union of Archaeologists of Ukraine predicts that there will soon be an increase of finds from the Velykyi Luh area in auctions. The Khortytsia National Reserve also reports a "real boom in black market archeology."

"The point is not so much that they can find something ancient and take it for themselves, but that they can damage the landmark itself. It becomes unrepresentative of science. It will be impossible to periodise it, to determine what kind of culture it is, and what kind of site it is," says Mykhailo Mulenko, a representative of the reserve.

By flooding Luh, the Soviet government caused the first catastrophe; by blowing up the hydroelectric power plant, the Russians caused the second. While historical circles discuss artefacts and heritage preservation, naturalists and ecologists debate the restoration of the reservoir or the meadow.

Ivan Moisiienko, a doctor of biological sciences and board member of the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group, advocates not restoring the hydroelectric power plant. He told the BBC that it is common practice in Europe to destroy dams and restore the natural flow of rivers. In his opinion, Ukraine should follow the same path to restore Velykyi Luh.

"The chance to restore the unique Velykyi Luh should not be lost. It will open up an area of almost 200,000 hectares, where the ecosystems of the Ukrainian steppe, meadows, and floodplain forests used to be," said Moisiienko.

Mykhailo Mulenko believes that there is no point in hoping for the revival of the Luh as it was before the construction of the hydroelectric power plant. The scientist explains that the hydrological facilities that used to be in Velykyi Luh — a network of small rivers, streams, and lakes — are now all under a layer of silt. Even if everything is cleaned up, the hydrological regime is unlikely to be restored. Before, the Dnipro was unregulated, and with the spring floods, water flowed continuously from north to south. This created the wetland vegetation of the Luh and formed meadows.

Nowadays, there is a cascade of other hydroelectric power plants above the Kakhovka reservoir. At its maximum capacity, the Dnipro HPP can produce a certain amount of water — a volume, Mulenko says, that cannot even be compared to that of the unregulated Dnipro.

"Even if a network of hydroelectric storage tanks is constructed there, there will still be a water shortage. It is possible to make some kind of recreational area, or even agricultural land, but it will no longer be the Velykyi Luh," the scientist says.

Refat Chubarov, the head of the Qırımtatar Milliy Meclisi, told Svidomi that the temporarily occupied Crimea has enough water in its reservoirs for this year because of frequent rains in the spring. There is a problem with the agricultural sector — the Russians have planted a lot of rice, which will not ripen because it requires a lot of water.

The North Crimean Canal starts from the Kakhovka Reservoir. Prior to the occupation, the canal provided 85% of the freshwater needs. In April 2014, Ukraine stopped supplying water to Crimea through the canal. On February 24, 2022, Russians seized the main building of the canal in Tavriisk, Kherson region, and the Kakhovka HPP, after which they resumed the water supply. After the Kakhovka HPP was blown up and the Kakhovka reservoir was shallowed, the water supply to Crimea stopped. The dam needs to be rebuilt in order for water to start flowing again. Chubarov claims that Crimea cannot live without the Dnipro water.

The state immediately announced that a new hydroelectric power plant would have to be built, and water would be accumulated in the upper reservoirs to fill the Kakhovka reservoir as soon as possible after de-occupation. The Kakhovka HPP regulates the flow of the Dnipro River to supply electricity, irrigation, and water to the arid regions of southern Ukraine.

"It will take at least 5 years to build a new plant in a 24/7 mode. It requires at least ₴1 billion. We still don't know the full extent of the damage: not only the plant but also the railway lines, water, and gas supply have been damaged. This is a complex hydroelectric facility that will take time to rebuild. We are currently developing a project for the station's location," said Ihor Syrota, CEO of Ukrhydroenergo.

The project is being developed taking into account possible military threats: some will be located underground, while others will be built so massive that they can withstand powerful attacks.