Dovzhenko's legacy: the development of a Ukrainian film studio

To follow the path of Oleksandr Dovzhenko, it is enough to watch his key films, such as 'Earth' and 'Shchorsʼ. Or read his iconic works — 'The Enchanted Desna' and 'Ukraine in Flames'. When we think of Dovzhenko, we see an established filmmaker and writer, almost a Soviet propagandist.

His time in Odesa remains in the shadow of his busy work periods in Kyiv and Moscow. But Dovzhenko became a film star in Odesa. He made the films he wanted to make, not the ones the Soviet government wanted him to make. The Odesa period was not Oleksandr Dovzhenko's heyday as a director but changed Dovzhenko into a person.

Read the full story about Oleksandr Dovzhenko's work and life in Odesa, as well as the imprint that the early period of his work left on the city and the film studio.

How Oleksandr Dovzhenko ended up in Odesa

The sun-drenched Frantsuzskyi Boulevard is much quieter than the busy central streets of Odesa — Deribasivska and Lanzheronska. Here, you can reach the sea and hear it — the waves breaking over the noise of cars and trams. It is also the location of the Odesa Film Studio.

Almost a hundred years ago, Oleksandr Dovzhenko also walked along the boulevard to the film studio. A little-known illustrator and graphic artist at the time, Dovzhenko came to Odesa from Kharkiv in 1926: he was invited to work as a director at the film studio at the suggestion of Yurii Yanovskyi. Yanovskyi was the editor of the First Film Factory of the All-Ukrainian Photo-Cinema Administration (VUFKU), one of the first names of the Odesa Film Studio.

Dovzhenko went to Odesa to make his first film 'Vasya. The Reformer'. It was an opportunity for him to show himself and express himself in something different. In Kharkiv, Oleksandr Dovzhenko tried to become a writer, but to no avail. The local public did not like his stories very much. The Free Academy of Proletarian Literature (VAPLITE) members did not accept Dovzhenko into their circle. But there he met Mykola Khvylovyi, Pavlo Tychyna and Yurii Yanovskyi.

The friendship with Yanovskyi became one of the key moments in Dovzhenko's life.

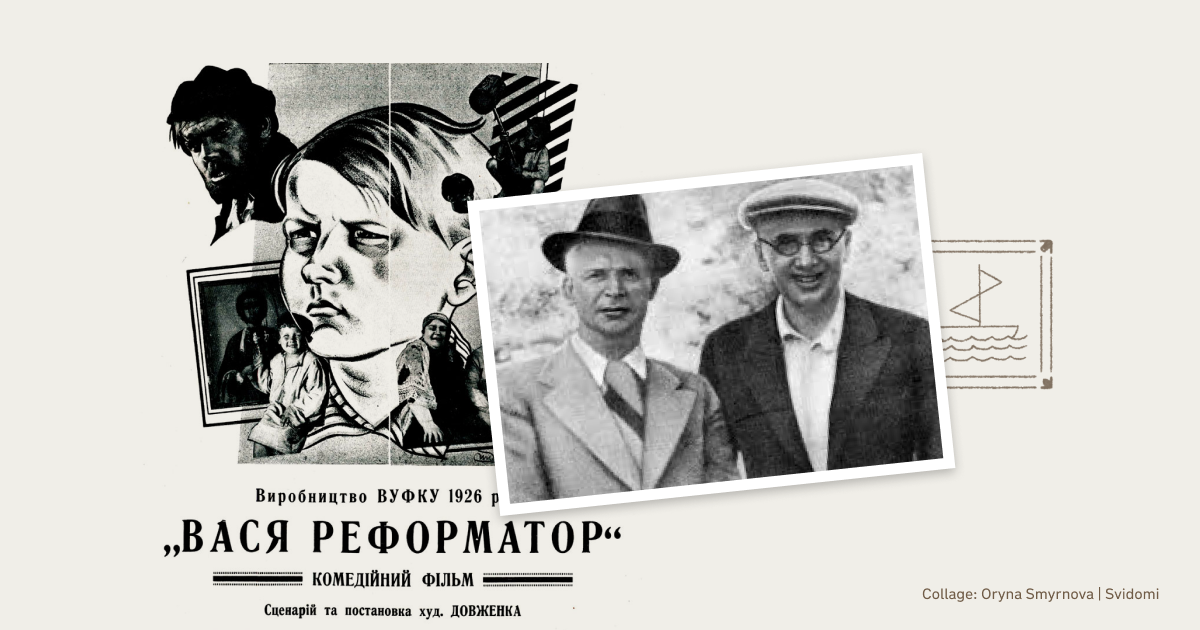

Yurii Yanovskyi came to Odesa Film Studio to work as an editor. The first thing he did was represent the interests of Oleksandr Dovzhenko. Yanovskyi took two scripts — 'Vasya. The Reformer' and 'Love's Berries' put them into production, paying his friend with money from the Odesa film studio. In this way, he supported Sasha Dovzhenko, and Dovzhenko lived on this money," says Andrii Osipov, the director of the Odesa Film Studio.

Osipov has studied Dovzhenko's life and work for over a year, partly because the studio is currently making a biopic about Dovzhenko. There is a whole shelf of books about Dovzhenko in his office, and on a large board are photos of the participants in those events.

'They say that Dovzhenko was a bit careless with the filming, inattentive, and maybe insecure. Is that true?' I ask Andrii Osipov about the process of making 'Vasya. The Reformer'. This is Dovzhenko's debut film, and much has been written about it, even more than some other films made at the Odesa Film Studio.

'You have to understand that Dovzhenko was asked to finish this film. At first, Favst Lopatynskyi shot it, but he left the film. That's why Dovzhenko was unhappy with the film. He treats his other films carefully, almost in perfection,'

Andrii tells me.

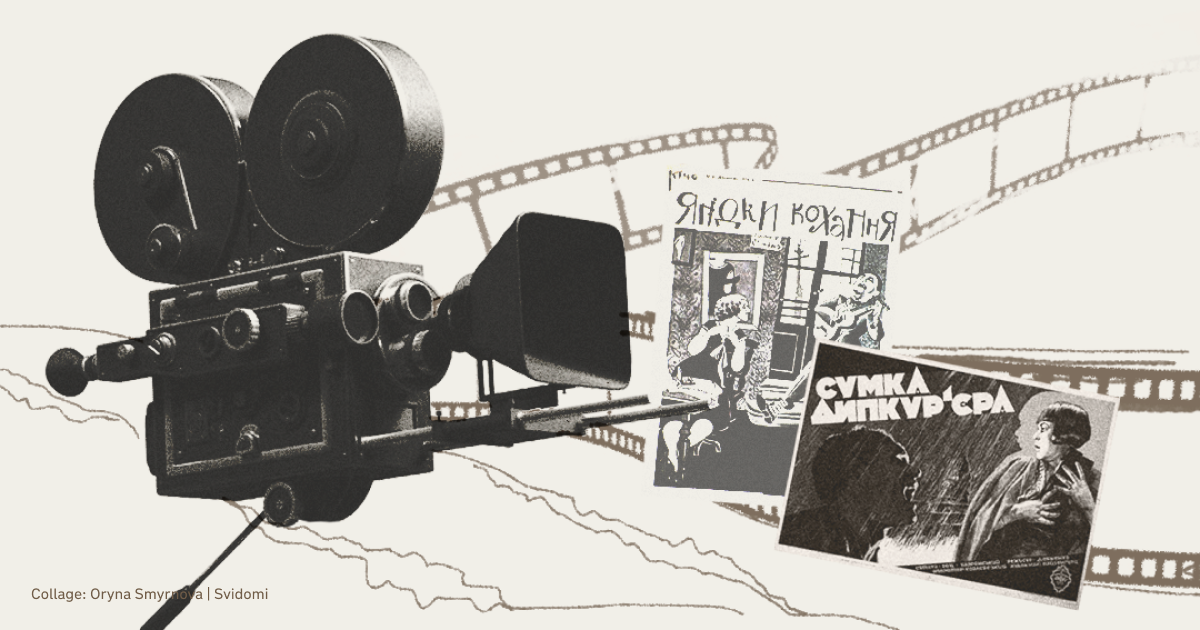

Despite his dissatisfaction, Dovzhenko continued to make films for the studio for another three years until 1929. With his subsequent films, 'Love's Berries' and 'The Diplomatic Pouch', Dovzhenko's fame grew. In Odesa, he became almost a star for the time.

'Everyone who made films in Odesa at that time became a star,' says Osipov. Dovzhenko gained influence with the authorities. He lived in the best apartments, women fell in love with him, and he was accepted into the high society of the time.

Oleksandr Dovzhenko was already married to Varvara Krylova when he went to work in Odesa. The move caused a crisis in their relationship. Taking advantage of his quickly acquired celebrity status, he courted other women and even had a brief affair with the ballerina Ida Penzo. Yurii Yanovskyi also courted Ida.

'Ida had an easy-going personality and did not want to choose between them. Their love affair lasted six months, and at the end of 1926, Dovzhenko fell in love with another woman, Olena Chernova. And then he met the actress Yulia Solntseva, who became his second wife,' says Andrii Osipov, describing the director's life between films.

Yurii Yanovskyi would later describe this love story between himself, Ida Penzo and Oleksandr Dovzhenko in his debut novel 'The Ship Master'.

Like Kharkiv, Odesa experienced a cultural boom in the twenties of the last century. Theatres and cabarets sprang up, and artists and writers came to work and relax. The film studio was one of the centres that attracted artists to the city.

'These metamorphoses in the mid-1920s made Odesa, after Kharkiv, the second epicentre of Ukrainian and avant-garde cultural life. And Dovzhenko was one of its symbols. Even though he was not rooted in purely Odesa narratives and myths, Dovzhenko brought his vision and style to the city. Odesa at the same time entered into a synthesis with the southern sense of burlesque, Black Sea carelessness and the chic of local bohemianism,' says Oleksandr Teliuk, head of the Dovzhenko Centre's archive.

The screenplay for Dovzhenko's film 'Zvenyhora' was written by Maik Yohansen, a Ukrainian writer and one of the founders of VAPLITE. He was executed in 1937, like many other writers of the Executed Renaissance.

Oleksandr Dovzhenko escaped this fate. Although his second wife, Yulia Solntseva, could have been an NKVD (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs in the Soviet Union — ed.) agent. Dovzhenko also met her in Odesa.

Even Dovzhenko himself could have been recruited as early as 1920 in Zhytomyr, where he had fled from the Bolshevik occupation of Kyiv and the final destruction of the Ukrainian People's Republic. This is because from 1918 to 1919, Oleksandr Dovzhenko was a soldier in the UPR army and took part in the suppression of the Bolshevik uprising at the Arsenal factory in Kyiv.

"Somehow, after the Red Army concentration camp, he got into diplomatic work. This probably means he was connected with the Secret Service: all diplomats are somehow connected with the Secret Service. In Warsaw and Berlin, his diplomatic work involved particular activities. The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic asked the best people who had left the country after the Bolsheviks came to power to return. Some of the people who Dovzhenko and his colleagues persuaded were later subjected to repression,"

says Osipov.

At first glance, Dovzhenko's figure in the history of Ukrainian cinema seems somewhat ambiguous. But his time in Odesa is the most carefree of his career. Then came the repressive 1930s for the Ukrainian intellectual and creative elite and the Second World War. After the war, Dovzhenko was not allowed to settle in Ukraine and lived only in Moscow, working at Mosfilm. He died there in 1956. He wrote in his diary: I will die in Moscow without ever seeing Ukraine!

The creative legacy of Oleksandr Dovzhenko

The film 'Vasya. The Reformer' (1926) has not been preserved. Researchers consider it lost. The director himself did not like it, but it brought Dovzhenko his first success in his work in general.

'This film saved the studio. If Oleksandr Dovzhenko had not agreed to make it, the money spent on the film would have been lost. And so they were able to return it,' says Andrii Osipov.

So Dovzhenko stayed with the studio and made 'Love's Berries' (1926), which he was also unhappy with, and later 'The Diplomatic Pouch' (1927).

'Yurii Yanovskyi again played a critical role, greatly influencing film studios. He did everything to ensure that Dovzhenko got the most attractive script of the time. In 1926, the most fashionable topic was the death of the diplomat Theodor Nette (a Soviet diplomatic courier who died during a terrorist attack on a Soviet train in Berlin — ed.). Poems were dedicated to the event, and ships and factories in the USSR were named after Nette. A film studio in Odesa was commissioned to make a film. Strangely, Dovzhenko was assigned to the film because he was still a beginner. And it was a state commission, a lot of money, and many applicants. But the most exciting thing is that Dovzhenko managed to do it," Osipov says of the film's history.

This film finally established Dovzhenko's status as a famous director. He shot 'The Diplomatic Pouch' in an adventure style, imitating the German silent adventure films of the time. With this film, Oleksandr Dovzhenko began to develop his style with more dynamic editing and experimented with framing and camera optics to create expressive and exciting shots. The film was a box-office success, ran for a long time in cinemas, and was also shown abroad.

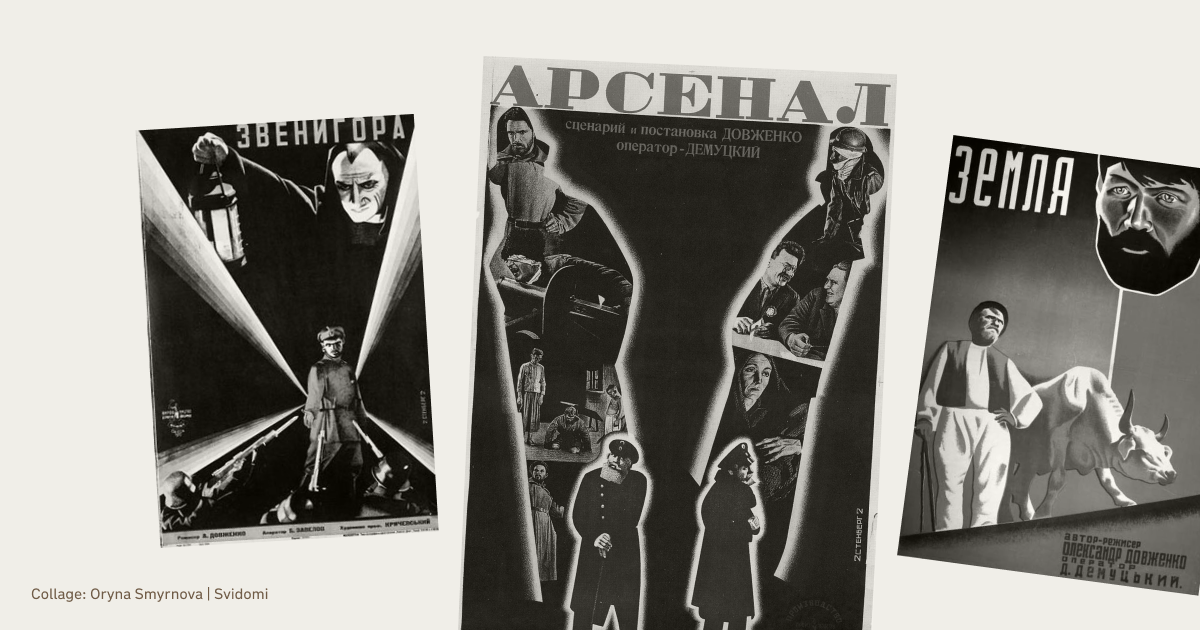

In 1926, Yurii Yanovskyi was dismissed from the film studio under unknown circumstances. However, this dismissal did not affect Oleksandr Dovzhenko's position. Although he failed to make a satirical film about the last emperor of the Russian Empire, Tsar Nicholas II, he began to develop his trilogy 'Zvenyhora', 'Arsenal' and 'Earth' in Odesa.

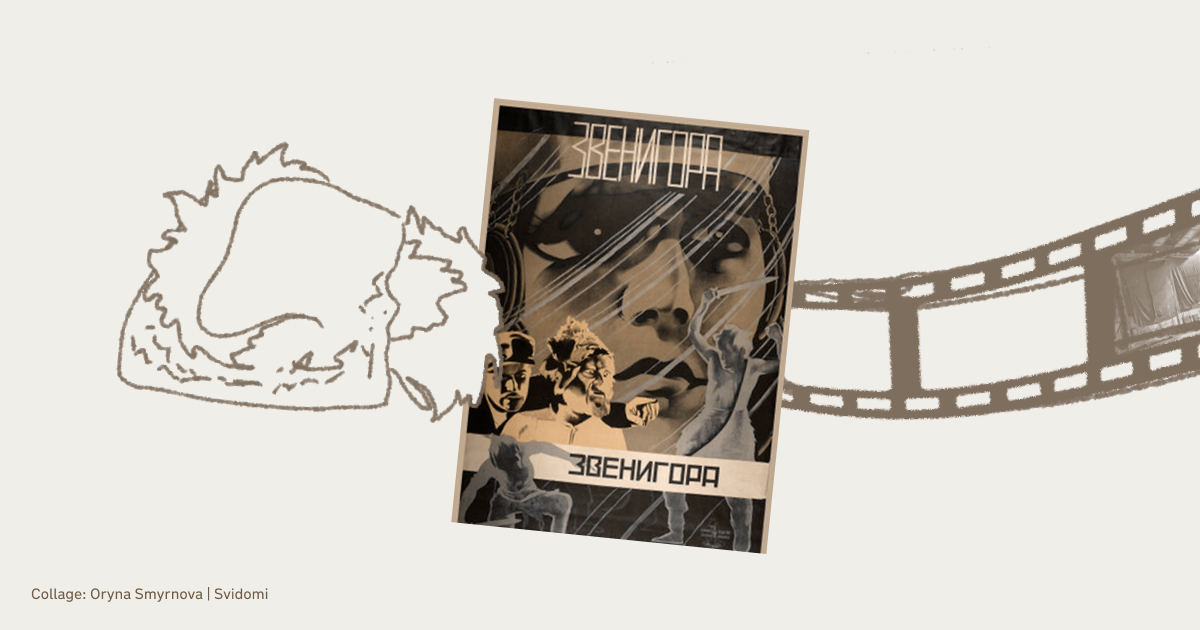

'Zvenyhora' (1927) tells the story of the legend of Scythian treasures buried by the Haidamaks (a popular movement of rebels against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth on the right bank of Ukraine in the 18th century — ed.). The unnamed protagonist, ‘grandfather’, tries to find them, a prototype of the peasantry stuck in the past. The film covers over two thousand years of Ukrainian history, from the Scythians to Soviet Ukraine.

Maik Yohansen and Yurii Tiutiunnyk wrote the script. But Oleksandr Dovzhenko almost completely rewrote it while he was working on it. He wanted the film to be his 'Iliad', accessible only to experts in Ukrainian history. Vasyl Krychevskyi, a famous Ukrainian architect and artist, helped Dovzhenko collect ethnographic material for the film. The film ends, however, with the glorification of socialist industry. One of the characters, the grandson of ‘grandfather’ Tymish, gives up the search for the treasure and chooses to work for the benefit of the Soviet state.

Oleksandr Dovzhenko changed the script so that the names of Maik Yohansen and Yurii Tiutiunnyk did not appear in the credits. Yohansen wrote in 1930 that he had "written (together with Yurtyk) the script for 'Zvenyhora' (which was later changed and spoiled by O. Dovzhenko)".

'Zvenyhora' gave impetus to the avant-garde genre in Soviet cinema, took the Ukrainianisation of cinema at the Odesa Film Studio to a new level, and finally cemented Oleksandr Dovzhenko's reputation as the leading Ukrainian film director. Even the positive coverage of Soviet industrialisation did not prevent Soviet propaganda journalists and critics from accusing Dovzhenko of 'excessive bourgeois nationalism'.

Oleksandr Teliuk, head of the Dovzhenko Centre's archives, says we can and should talk about the birth of Ukrainian cinema from when 'Zvenyhora' was released.

'Dovzhenko became a symbol of Ukrainian cinema at home and abroad for decades. But if the director's next landmark films, 'Earth' and 'Shchors', expressed more unfortunate social changes in post-Soviet Ukraine, the early Odesa period remained an escapist, youthful space of risk, experimentation and freedom,' he says of this phase of Dovzhenko's work.

Dovzhenko's Odesa period finished with the film 'Arsenal'. This film tells the story of the uprising at the Arsenal factory and glorifies the Bolshevik workers. He was criticised for this film because it was seen as 'a concession to the authorities, who never stopped accusing Dovzhenko of nationalism'. Dovzhenko would shoot his third film, 'Earth' (1930), in Kyiv at the new VUFKU film studio.

He went on to make 'Shchors' and 'Michurin'. However, these films do not have the same lightness and humour as his early films from the period of his work in Odesa. The film 'Ivan' (1932) tells the story of the construction of the Dnipro hydroelectric power station — today, researchers consider it a propaganda film. Oleksandr Dovzhenko did not like the film.

Oleksandr Teliuk believes that Oleksandr Dovzhenko can be considered a Soviet propagandist because, ideologically, all cultures at that time had to obey the totalitarian state, including cinema.

'The scale of Dovzhenko's personality contained these complex contradictions of his era. He was at once a leader of Ukrainian cinema, a singer of the nature of his homeland, and an innovator of the European avant-garde. But he was also a conformist, dependent on the narratives of power, tired of creative restrictions and even an anti-Semite. This makes Dovzhenko a rather uncomfortable, but at the same time, human (Soviet narratives have instead cast him in bronze) historical figure. On the other hand, these complex contradictions were not a feature of one particular artist but a tragedy of several generations of Ukrainian artists, who had to choose between the model of a servile socialist realist poet and a fighter condemned to death and silence and often bitterly balanced somewhere in between,'

Teliuk describes the image of Oleksandr Dovzhenko as a director.

Odesa Film Studio today

Standing in front of the main entrance to the studio, you don't notice its size. Behind the gates and a high fence are five pavilions, the main office and the old building of the first pavilion. The streets between the pavilions are lined with outdoor props.

Walking through the studio courtyard between the pavilions, you can see the need for such a massive fence — the sounds of cars and trams are barely audible. But you can hear the sea. My guide, Andrii, tells me that the studio has a swimming pool that is used to film miniature ships for sea scenes in films.

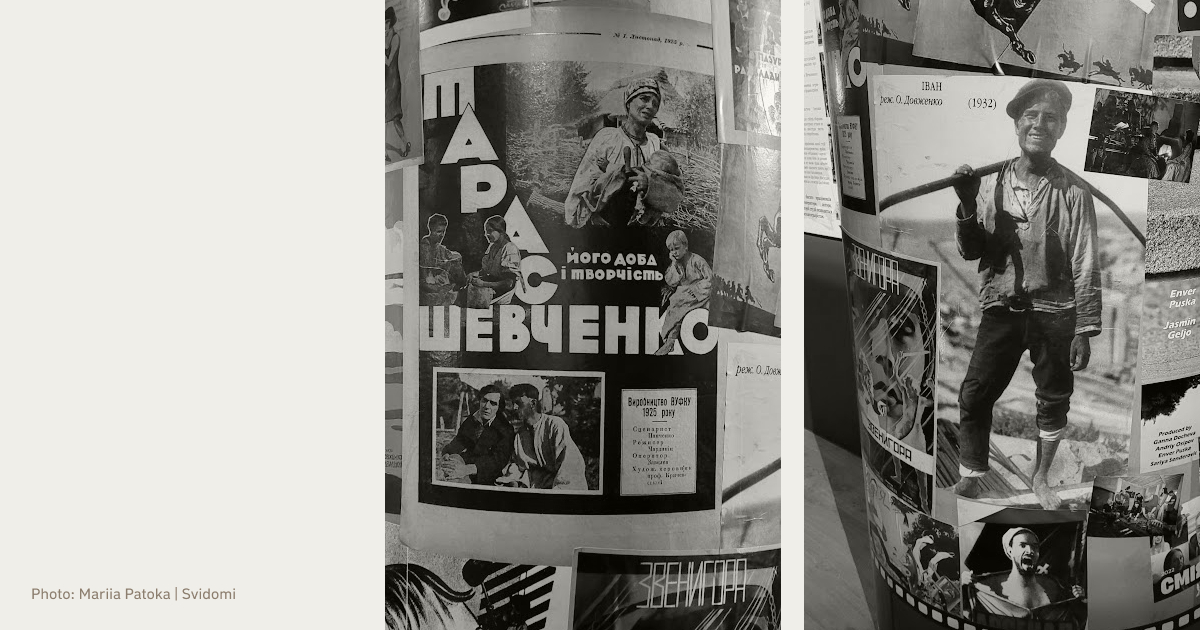

The fifth pavilion is a museum. It tells the studio's story from its beginnings to the present day. The Odesa Film Studio remained one of the largest film studios in Ukraine both in Soviet times and today.

It was the location for such Soviet films as 'The Three Musketeers: D'Artagnan' (1978) and 'The Place of Meeting Cannot Be Changed' (1979). Although these films are considered cult in the USSR, they were shot in Russia, and some actors, such as Mikhail Boyarsky, support Russia's war against Ukraine. Their work is banned in Ukraine, as is the screening of films featuring them. The museum has props from filming these films and reconstructed interiors from some scenes.

I ask Andrii if visitors only come to the film studio to learn about the history of these films.

'It used to be like that. People came to find out more about these famous Soviet films. But since the full-scale invasion began, the focus has changed. Museum visitors want to learn about Ukrainian culture. Ukrainian cinema culture was vividly represented by the period of the VUFKU, Yanovskyi, Kurbas, Yohansen, and Dovzhenko. For many people, these gaps are simply not filled with information because their films are not so promoted, popularised or digitised,' Andrii tells me as we walk through the museum's poster-strewn hall.

Posters of almost all films made at the Odesa Film Studio and preserved in various archives are reproduced here. Among the posters from the 1920s, there is a reproduction of the poster for 'Taras Shevchenko' (1926), and among the modern ones, you can see the poster for 'Taras. The Return' (2019). In this way, two films about Taras Shevchenko were made in the same film studio — a Soviet film and one made in independent Ukraine.

Andrii tells me that although it was the time of the USSR, Ukrainisation still had an impact, including on cinema.

In the 1920s, the film studio worked to revive Ukrainian culture. They made films about Ukraine and Ukrainian things. Odesa was a part of that, and we should not forget that.

However, after the Soviet authorities curtailed the policy of Ukrainisation in 1932, the film studio also came under the total influence of Soviet propaganda and then Russian culture. Even after the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Russians continued to shoot their films at the studio. They left in 2014, after the occupation of Crimea and the territories of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

'The crisis was significant,' says Andrii Osipov of the studio's post-2014 period. But the departure of Russians from our market triggered the rapid development of our industry. Our drama school developed rapidly, and the scriptwriters, directors and cinematographers were also doped up. It would be a lie to say that all the problems have been solved, but in terms of the overall level, Ukraine is at a good production level in the world of cinema, which is shown by the number of films released every year. Ukraine won prizes at the best film festivals and so on. In a short period, we managed to develop cinema,' says Osipov about the current development period of Ukrainian cinema, which is already being called a 'renaissance'.

'But the war clipped our wings,'

he notes.

The Odesa film studio, like the whole city, has suffered repeatedly from Russian shelling of the city. In June 2023, a missile strike damaged the front door of the main office and blew out the windows of the film processing shop. However, the studio remains open, and filming continues.

Next to Frantsuzskyi Boulevard is Oleksandr Dovzhenko Street. To some extent, his name is inscribed on the city's canvas, but the association 'Dovzhenko — Odesa' is not the first thing that comes to mind.

I ask my interlocutors, the guide Andrii and Mr Andrii, the director, whether Odesa should compete with other cities to make Dovzhenko's legacy more tangible.

'I don't think so,' the guide told me, 'Dovzhenko started in Odesa, and we should be proud of that because he is an excellent director. But there is no need to compete. All periods of his creative activity should flow smoothly into each other so we can talk about a holistic picture of Dovzhenko's perception as a director.'

The film studio director believes that Oleksandr Dovzhenko's Odesa period is not as noticeable as the Kyiv period, and it is worth highlighting this publicly.

'Yurii Yanovskyi is connected with Odesa. Ilf and Petrov, Ivan Bunin — this whole southern literary school is more associated with the city than Dovzhenko. But we are happy that one of the three most important directors for Ukrainian cinema lived and worked here. The second was Kira Muratova. It's a pity that the third, Serhii Parajanov, never worked in our film studio. Otherwise, we would have had all three,' says Andrii Osipov with a smile.