Slovo Building. How did the Executed Renaissance affect Kharkiv's cultural identity?

The Executed Renaissance was a literary and artistic generation of the 1920s and early 1930s in Ukraine that was exterminated by the Soviet government.

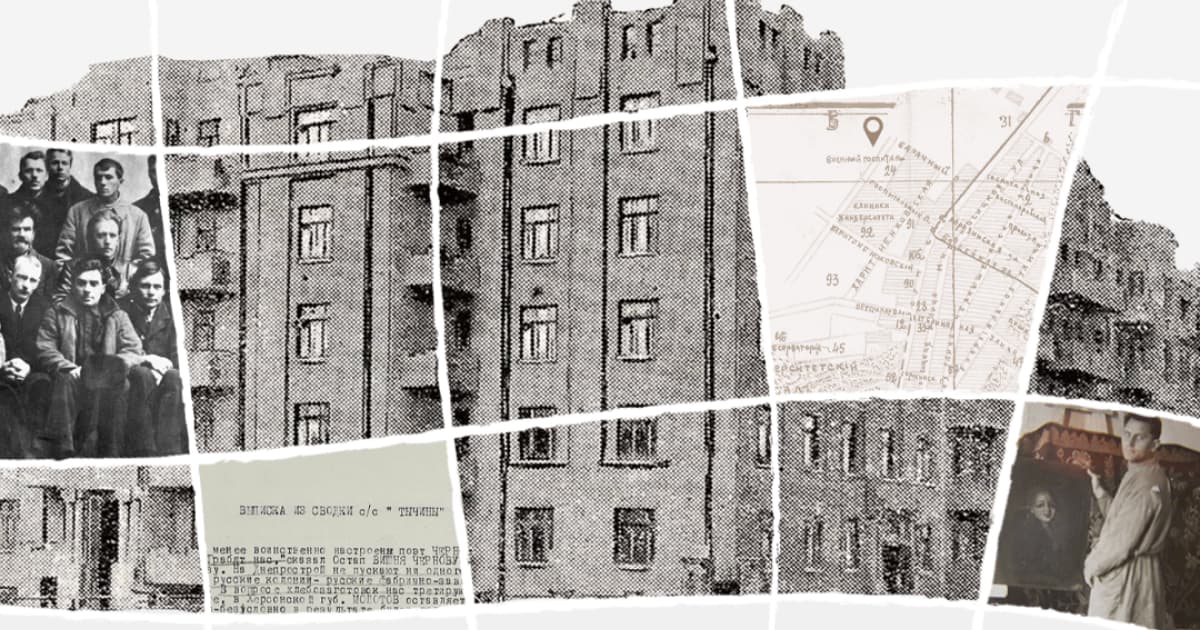

An example of Soviet repression and arrests was the Slovo Building, a six-storey residential building in Kharkiv constructed in the late 1920s. The architect Mykhailo Dashkevych designed it in the shape of the letter "'C'" — hence the name (Slovo — Слово ("Word") in Ukrainian — TN).

Between 1933 and 1938, the Soviet authorities persecuted more than 70 artists who lived in the house; 11 of them were shot in the Sandarmokh woods. Later, all the artists who died during this period were called the Executed Renaissance.

"Slovo gathered artists in the early 1930s when their main contribution had been made, and there was less and less freedom to create," says Maryna Kutsenko, a researcher at the Kharkiv Literary Museum.

Read more about the emergence of cultural life in Kharkiv, the impact of the Slovo Building on the city's cultural development, and the perception of the building in the article.

The emergence of cultural life

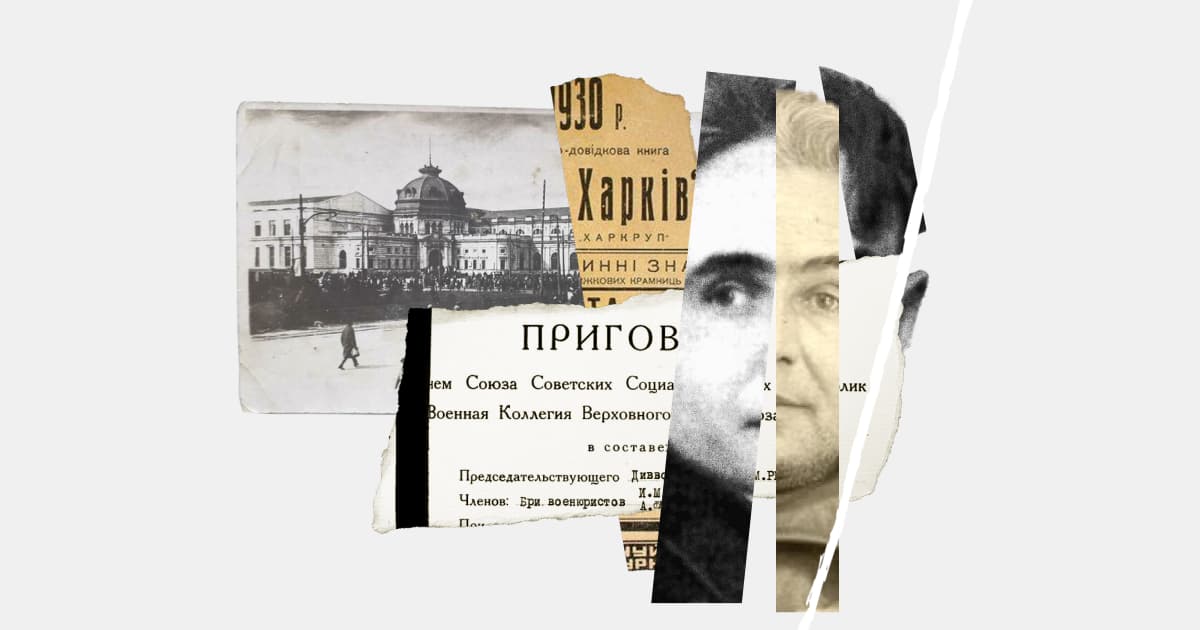

On March 10, 1919, the Soviet government proclaimed the creation of the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic. The capital was moved from Kyiv to Kharkiv, as the Soviet authorities wanted to convince people that Ukraine's existence began in the Soviet era.

At that time, the city was in the spotlight, and as a result, it could not accommodate everyone who wanted to stay there.

At the same time, communal living was in style, and communal houses were built for employees of various enterprises. Housing co-operatives were founded, which built the apartments at their own expense,

explains Maryna Kutsenko, a researcher at the Kharkiv Literary Museum.

History of the Slovo Building

Kharkiv became one of the key centres for writers and cultural figures. The writers in the city were mostly newcomers from other towns, and their number was constantly growing. To solve the problem of housing, a cooperative was established in 1930, and the Slovo Building was built.

According to Soviet ideologists who were concerned with the working conditions of the writers' workshop, the house was supposed to be a paradise. The intelligentsia was to live in separate apartments with hot water and a telephone, which was later used for wiretapping.

The peculiarities of the time, the status of the city, and the large number of unsettled enthusiasts all combined to create the writers' house,

Kutsenko says.

At first, artists were allowed to work freely. In the 20s and 30s, the Soviet regime embarked on a course of Ukrainisation: newspapers and magazines were published in Ukrainian, theatre was thriving, and literary discussions were taking place. However, this did not last long.

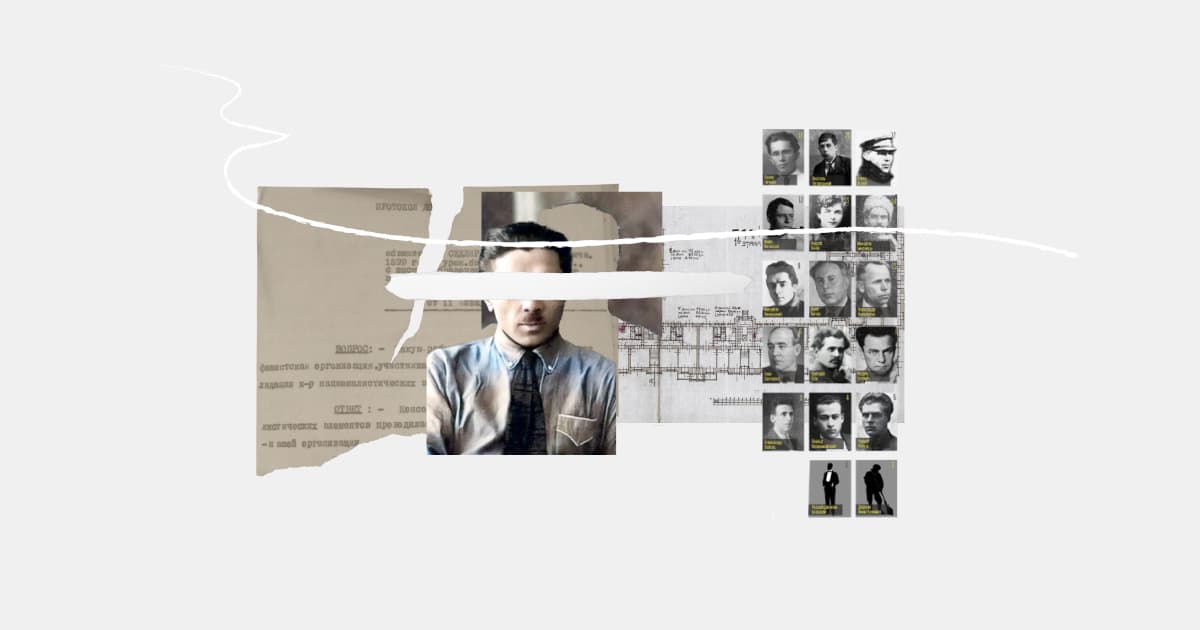

On May 13, 1933, writer Mykola Khvylovyi shot himself in the house. One of the reasons for this was the disappearance of his neighbour and friend, poet Mykhailo Yalovyi. He was a prose writer, playwright, screenwriter, and the first president of the VAPLITE literary association. For this reason, Yalovyi was charged with "participation in the grouping of counter-revolutionary figures among writers" and "creation of a counter-revolutionary fascist organisation that had the goal of overthrowing the Soviet government."

After that, the residents of the Slovo Building lived in conditions of constant repression and persecution.

The Slovo Building is an example of the beginning of the revival of Ukrainian culture, particularly in Kharkiv. When I think about what would have happened to Ukrainian culture if it hadn't been for the repressions, there would have been much more powerful literary and artistic processes,

says art historian Oksana Semenik.

The Soviet repressive regime culminated on November 3, 1937. Then, "in honour of the 20th anniversary of the Great October Revolution", director Les Kurbas, writers Mykola Kulish and Valerian Pidmohylnyi, poets Marko Voronyi, Mykola Zerov, and other artists were shot dead in the Solovki Special Camp. The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs of the USSR killed 1111 people, including 287 Ukrainians and people associated with Ukraine.

By 1938, the Soviet authorities repressed the residents of 40 of the 66 apartments in the building. 33 people who lived there were shot dead, and more than 70 were repressed. After Ukraine regained its independence in 1991, their rehabilitation was slow, and their names were not revealed for a long time.

Kharkiv residents' perception of the building

In the 1920s, Ukrainian writers encountered cultural resistance from some Kharkiv residents. "Here we can recall Myna Mazailo (a play about a man who decided to change his Ukrainian surname to a supposedly more prestigious Russian one — ed.) by Mykola Kulish, when the audience shouted that they did not understand the play," Kutsenko recalls.

The artists had to struggle with the realities of the time, but people needed more time to get used to the new art. For example, some of the public did not accept Les Kurbas' innovative performances. He combined all kinds of arts in his productions: music, plasticity, make-up, theatre design, lighting, costumes, recitation, acting, and directorial concept. The director promoted the idea that all the components of a performance work for the overall idea of the plan. Over time, the performances began to receive a response.

After the executions and repressions, the building turned into an ordinary residential building. The Soviet authorities kept silent about the torture and murder, so some residents were not even aware of the building's history.

According to the employee of the Kharkiv Literary Museum, for a long time, only memorial plaques reminded people of the history of the house: the first one was dedicated to Pavlo Tychyna, and the second one had a longer list of writers who lived there.

When I came to work at the Kharkiv Literary Museum in 2015, scholars and literary experts were talking about the Slovo Building, and they went there on a 'pilgrimage' on the Mykola Khvylovyi Remembrance Day. Sometimes we visited the descendants of the original residents, who still lived in several apartments. From time to time, we organised excursions,

explains Maryna Kutsenko.

The residents had different attitudes to the visits. Some were unwelcoming, others joined the tour and added their stories, and others just discovered they lived in an unusual house. Over time, discussions began to take place about how to make Slovo noticeable in the city.

How Kharkiv changed through cultural development

Art historian Oksana Semenik says that the Slovo Building is the result of a powerful cultural movement in Kharkiv that developed even before the creation of a physical space for artists.

According to her, the perception of the Slovo Building over the centuries can be compared to the way people talked about the Executed Renaissance. The Soviet government concealed the facts of the murder of Ukrainian artists, so people did not even know that they could live in the residence of the Ukrainian intelligentsia.

Maryna Kutsenko notes that the Slovo Building is a symbol that makes it easier to talk about the artists who lived there. However, the house did not cause the emergence of talent in Kharkiv. On the contrary, the idea of creating such a space arose because many artists gathered in the city.

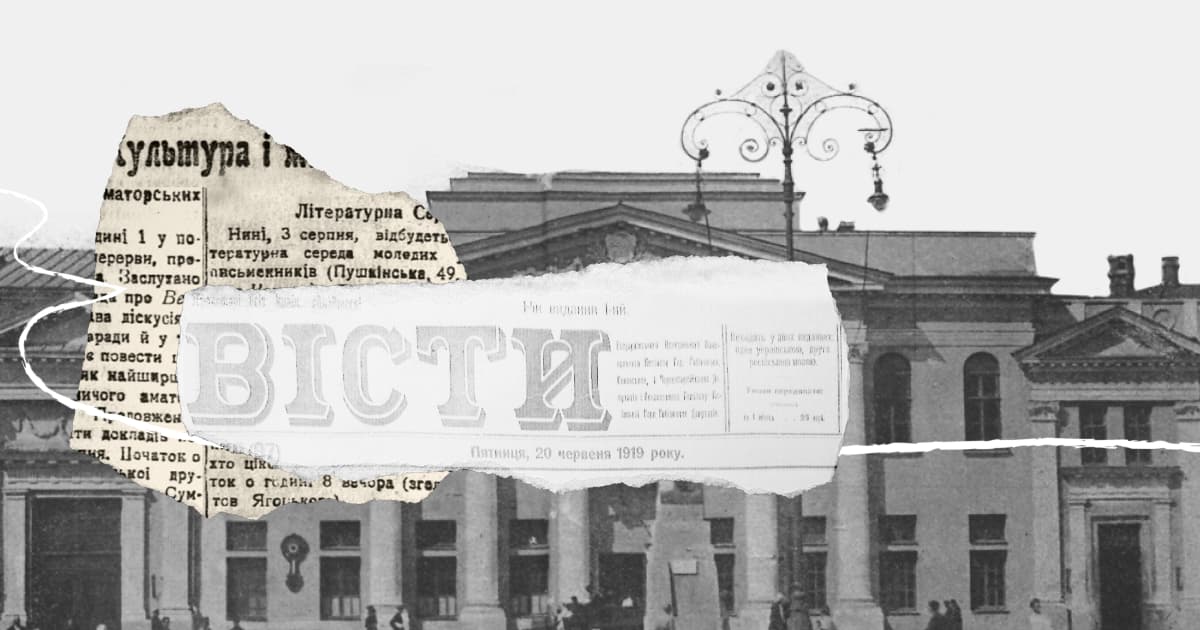

Many cultural centres changed the face of Kharkiv in the 1920s. These included the editorial offices of the Visti VUTsVK (News of the All-Ukrainian Central Executive Committee — TN) and Selianska Pravda newspapers, where the literary group Hart was formed; a peasant house on Pavlivskyi Square, where the Pluh Peasant Writers' Union met; and Les Kurbas's Berezil theatre.

Writers, theatre workers, scientists, artists, and musicians improved the cultural level of the population, instilled good taste and interest in Ukrainian content, and made creative experiments. They considered this period to be a cultural revival,

says Maryna Kutsenko.

Ukrainian writer Serhii Zhadan, as reported by Oksana Semenik, said that his contemporaries were united and inspired by Slovo in the 1990s. They had an understanding that they were close to the homes of people who shaped Ukrainian culture but were destroyed.

This helped them to perceive the artists as real people who went to the same cafes and restaurants,

the historian adds.

How does the Slovo Building live, and what is its symbol today?

The house has become a bridge between the artists of the Executed Renaissance and the present.

In recent years, information about the building has become widely known. Slovo became known not only to Kharkiv residents,

says Semenik.

Since 2020, a literary and artistic residence has been operating in one of the apartments. Artists and scholars are once again living in Slovo, and lectures, concerts, and presentations are taking place. Even amid a full-scale war, the activities continue.

Slovo is perceived as a symbol of the Executed Renaissance. During the period of the full-scale invasion, this symbol has become even more relevant because we draw parallels between how our culture was destroyed then and how it is now,

says the researcher at the Kharkiv Literary Museum.

On March 7, 2022, the Russian military shelled the landmark. None of the residents were killed, but several apartments were damaged.

It is quite natural for Russians: they have always destroyed our culture. However, this time they will not succeed. Russians are barbarians. And we will rebuild Slovo,

said Zhadan.