Donetsk and Luhansk regions: European heritage, identity and Soviet myths

Ostheim, Libental, New York, Blumenfeld, Bunge, Mariental — have you heard of these towns and villages in the Donetsk region? Probably not, because they all received communist names during the Soviet period, such as Novhorodske or Yunokomunarivsk. At the same time, the settlements also received a fictional (pro)Russian history.

The Soviet authorities distorted the perception of eastern Ukraine, as well as destroyed historical monuments and documents. How, then, can we discover the true historical heritage of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions?

At least via films. On September 21, Ukrainian cinemas released the film Eurodonbas by Kornii Hrytsiuk. The film debunks the myths about the eastern region of Ukraine being "built by the Soviet Union", and the film director himself focuses on the fact that more than 100 years ago, Donetsk and Luhansk regions were an integral part of the European world.

Read more about the European history of the East, Soviet myths and people's identity in the article.

European history of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions

In the 18th century, the Russian Empire, which included the left bank of Ukraine, began to acquire the features of a modern state, developing a professional army, officer corps, and bureaucratic apparatus. Then Catherine II destroyed the Cossack Hetmanate and the Crimean Khanate and began colonising eastern Ukraine by inviting Germans. This is how foreign colonies appeared in eastern Ukraine.

In the first half of the 19th century, Ukraine's industry had already generated more than 10% of the gross domestic product of the Russian Empire. At the same time, these enterprises were mainly light: Ukraine produced 80% of the sugar from beets and a third of the alcohol in the whole empire. It happened despite the significant duties imposed by St. Petersburg on Ukraine.

The situation changed after 1856 when Russia was defeated in the Crimean War (a war between the Russian Empire and the forces of the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain, the French Empire, and the Kingdom of Sardinia for dominance in the Middle East and the Balkans — ed.)

St. Petersburg was forced to change the social structure of the population in order to reform the Russian economy. Half of the workers in the empire's industry were serfs by 1861. They worked in the small manufactories or factories of their masters. Next, foreign investment had to be encouraged. So, St. Petersburg introduced a monetary policy, and foreign entrepreneurs joined their compatriots who were already living in the territories of Donetsk and Luhansk.

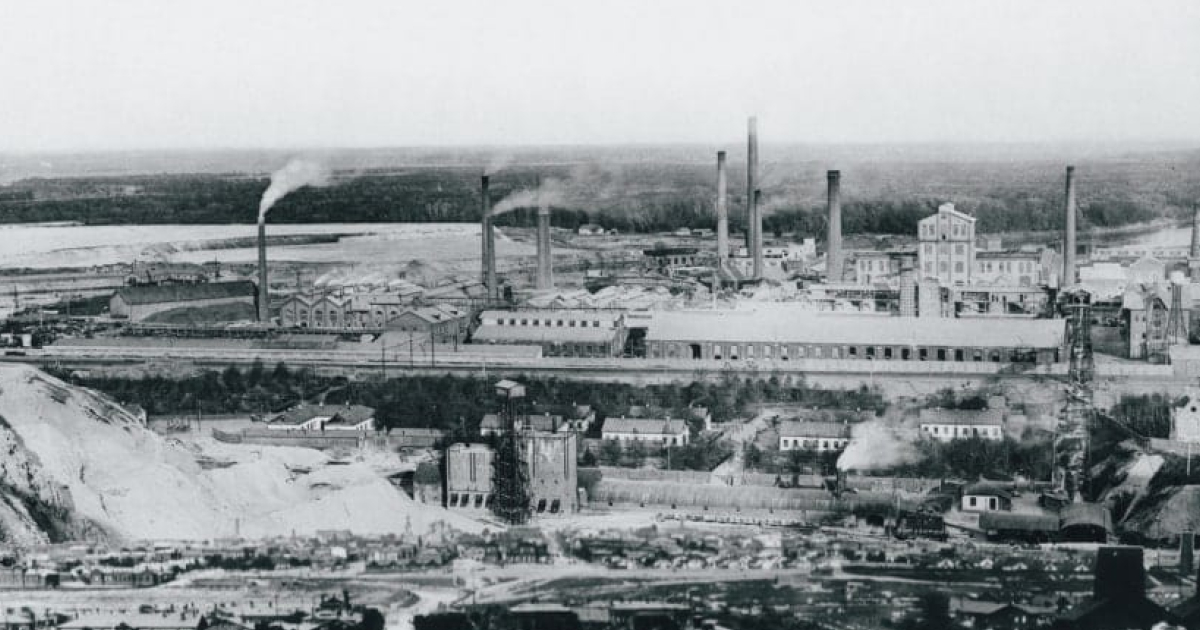

Among them was John Hughes, a British engineer from South Wales. He received an order from the Russian Empire to manufacture armour for the Russian navy. For this purpose, he was offered to head several already operating metallurgical plants, but Hughes refused. After inspecting the coal deposits in the Donetsk region, he decided to build a new plant there. In 1869, the working village of Yuzivka, which is now Donetsk, was founded.

French bankers and entrepreneurs founded a salt development company in 1883. After receiving a work permit, they bought up salt mines near Bakhmut and created an industrial enterprise with rock salt mines and a salt plant. Later, the company became one of the leaders in salt production and the largest of its kind in Central and Eastern Europe.

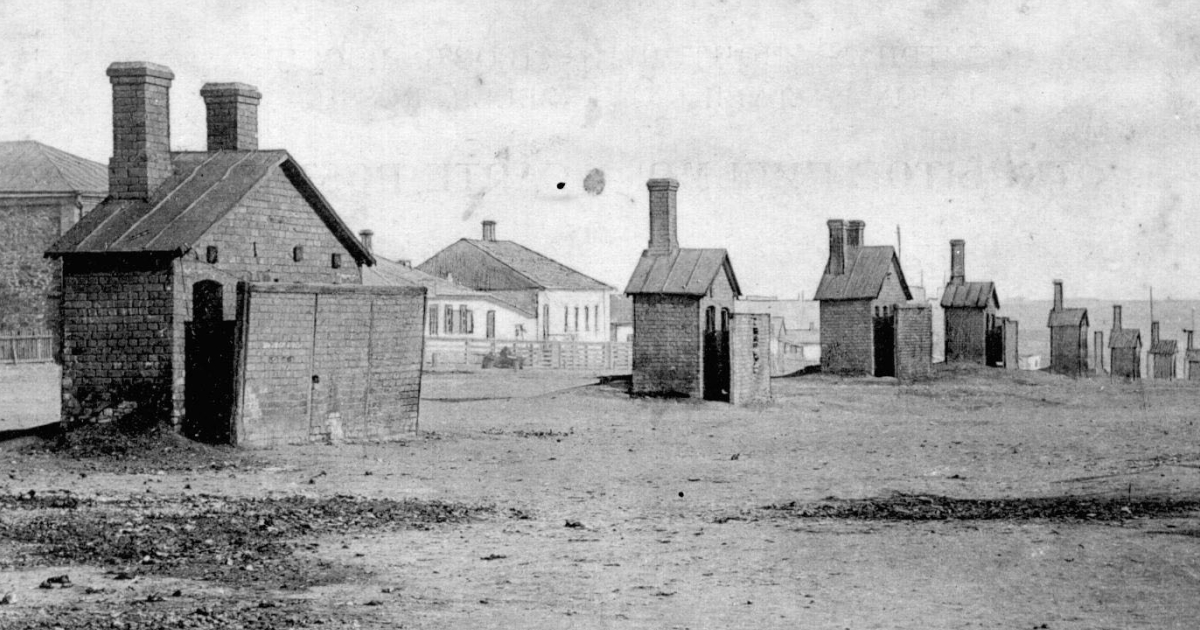

In 1892, Belgian engineer Ernest Solve established the Donetsk Soda Plant in Lysychansk. Later, this plant was renamed as Lysychansk Soda Plant. 33 facilities were built next to the plant: dozens of houses, a dormitory for 200 people, a school, a hotel and a hospital in the Art Nouveau style.

Lysychansk received the Belgian Heritage Abroad Award 2017 in February 2018. The city's complex of buildings was in the top five of the competition held annually with the support of the King of Belgium Foundation.

In 1896, German entrepreneur Konrad Gamper built a mechanical plant in Kramatorsk, and his compatriot Gustav Hartmann built a locomotive plant in Luhansk.

In Kostiantynivka, Belgian entrepreneurs built glass, bottle, chemical, mirror, and ceramic plants in five years, from 1896 to 1900.

At the beginning of the 20th century, about 1.4 million Ukrainians, more than 350,000 Russians, 80,000 Germans, 50,000 Greeks, 15,000 Poles, 5,000 Turks, about a thousand French, and half a thousand British lived in the Yekaterinoslav Governorate.

At the beginning of World War II, Soviet security forces deported about 100 thousand Germans from the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. So, New York, Rothfeld and Otilienfeld disappeared from the maps. Instead, they were replaced by Novhorodske, Krasna Poliana and Kuravliovka. According to the reference book German Settlements in the USSR, Before 1941, there were about 350 such cities, villages and hamlets in Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

Mentioning the European heritage of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions abroad

The memory of the true origins of the industry of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions was wiped out. Soviet propagandists denied the presence of foreigners in the East. Soviet propagandists could not admit that the core region for them emerged, thanks to foreign capitalists.

Larysa Yakubova, a doctor of history, says that the Soviet government constantly declared its so-called "sophisticated love for Donbas" but was, in fact, sadistic towards the region.

It [the Soviet government] supposedly loved it [the eastern region of Ukraine] very much and praised it with glorifying songs. However, its songs carefully destroyed all life here. The worst thing is that the Bolsheviks were able to convince the workers in this region that Donbas was an outpost of the Russian world without a European heritage. They spread this narrative around the world, too

Yakubova explains.

There are almost no historical archives or physical evidence of foreigners' presence in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions in the 18th century, the historian says. At the beginning of World War II, during the evacuation of archival documents to Russia, most of them burned. In 2014, the risk of losing the remaining documents increased due to the Russian occupation.

"In the first year of the occupation, Russians sold some documents from the archive in Donetsk on OLX. As a result, we will face (after de-occupation — ed.) the fact that our historically documented heritage is unlikely to remain. It is constantly being taken away or destroyed," Yakubova says.

Some documents about this period are available abroad in private collections, but Ukraine does not always have enough economic and physical resources to research them.

Another problem with Ukraine's representation abroad is that it is barely included in the history of Europe and the world. According to the historian, Ukraine was almost unknown until 2022. The point is not that researchers did not know the history of Ukrainians but that the issue of Ukraine did not arise in the mass discourse - they mostly perceived Ukraine as part of Russia.

In 2022 (after the start of the full-scale invasion — ed.), the world began to look at Ukraine with different eyes. For many years, we have been trying to show the place and importance of Ukraine in the history of Europe and the world. Foreigners remained largely indifferent to the issue because they were in the paradigm that, for example, Donetsk mine workers were part of Russia. They lived with the idea that only Russia had a role in the development and creation of eastern Ukraine.

says Larysa Yakubova.

The Soviet myth of Donbas. How to overcome it?

When we say "Donbas", we associate the region with a purely industrial one, but this is not the case. The Luhansk and Donetsk regions are landscape complexes, steppes, forest steppes, river floodplains, slopes, and most importantly, a European worldview and identity.

"Donbas was treated utilistically as a centre of coal and steel production. The Soviet government used it as a source of money and energy. Meanwhile, it said that people were supposedly living better since the arrival of the Bolsheviks. This was beneficial for propaganda both abroad and in Ukraine," explains Yakubova.

After regaining independence in 1991, Ukrainians spent their energy and resources fighting the narratives of the past instead of building visions and vectors for the future, Yakubova believes. As a result, Ukraine did not use the region for ecological and industrial tourism, as it did in Poland and Germany, where similar industrial centres were turned into art objects.

"The Donbas that Europeans developed probably no longer exists and will never exist. Russian aggression destroyed its identical remnants. Ukrainians have to revive not Donbas but Donetsk and Luhansk regions because the Donbas narrative was created by the Bolsheviks. We have to revive the real history through collective efforts," says the doctor of historical sciences.

Identity of the people of the eastern region

Larysa Yakubova recalls that before the Bolsheviks came to power, Donetsk and Luhansk regions were an ethno-national Atlantis (a mythical lost island or continent — ed.), which was later destroyed and cleansed. During the Holodomor (1932-1933), the Soviet authorities not only starved Ukrainians to death but also cleansed their identity and self-perception as individuals belonging to a particular cultural community.

Before the Bolsheviks came to power, different cultural communities existed in the region due to its multiethnicity. In Mariupol, there was a Greek autonomous Mariupol district where Americans later lived. In Bakhmut, the majority of people were Jews. Lysychansk has Belgian, German, and French heritage.

"This period [of foreigners settling in the East] made Ukraine one of the most interesting phenomena because of its multiethnicity, which created its own cultural processes. The principles of Greek proletarian and modern Jewish culture were formed here. Proletarian literature developed. But due to the massive terror of the late 1930s (a campaign of repression when the Soviet authorities killed more than 1,111 intellectuals — ed.), many processes lost their historical continuation," says the doctor of historical sciences.

The eastern part of Ukraine was cleansed by the Soviet authorities during the 20th century, from the 1930s to 1991, says Larysa Yakubova. As a result, the cultural, artistic and architectural visual range is minimal.

"In Soviet times, there were no opportunities for the formation of a full-fledged nation. The Soviet system was totalitarian and did everything to take away a person's subjectivity, which is essential for a citizen. Everyone was just a cog in the system, focused on the thoughts, desires and aspirations of the ruling core," Yakubova explains.

Donetsk and Luhansk regions were, as Yakubova says, a "test site" where they piloted this idea. Eventually, this led to the fact that at the end of the Soviet Union, the regional identity of a "Donbas resident" replaced the national one.

"First of all, it is the social structure of the population, which is approaching almost one hundred per cent proletarianisation. Secondly, it is an environment that has undergone ethnic destruction — a combination of the presence of many ethnicities in the community. As a result of proletarianisation, people do not comprehend this with their minds, but simply live in a non-national filtrate," the scientist explains.

As a result, the planned economy collapsed. It would seem that these constructs should have disappeared with it. However, it happened in a different way. "Oligarchic, in other words, first-generation capitalist Ukraine maintained the Soviet homogeneity of the region," Yakubova notes.

The role of the film Eurodonbas

The film breaks down stereotypes of the perception of eastern Ukraine, removing the reinforced concrete mask of the region. Experts, historians and local residents in the film talk about the region's past, which was destroyed and distorted by the Soviet government, erasing the names of European entrepreneurs from people's memory.

The film's protagonists take a tour of a hospital in Lysychansk built by Belgians. The locals show their houses, which they inherited from the Germans, Belgians and French. One of the families even managed to preserve the furniture used by foreigners.

"Hrytsiuk (Kornii Hrytsiuk, the film's director — ed.) managed to show the beauty of the people who used to live there and still do. It's about the terrible historical fate of a population that was repeatedly wiped out. The film brought back the understanding that the population here was primarily shaped by thoughts far from Moscow. They had their own lives until the Bolshevik regime intervened when people lost their essence and identity," says Larysa Yakubova.

For foreigners, the film shows that the waves of European civilisation are wide and distant. Historian Yakubova emphasises that such films prove that Ukraine and the West are historically related.

Donetsk and Luhansk regions are part of the Ukrainian world. It is important to go deeper into the history of the region to get rid of all the Kremlin narratives that have been imposed for centuries, not only within our borders but also outside them. It is important to recognise ourselves in the diversity of all manifestations of the Ukrainian world and to understand that Europeans were a large demographic indicator here

says Larysa Yakubova.