Bulgaria: to Moscow, transiting through Ukraine

On July 6, Volodymyr Zelenskyy arrived in Bulgaria. The spotlight was on a confrontational rather than cooperative story - a public spat between Bulgarian President Rumen Radev and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

Radev, a former military officer, is known for his pro-Russian stance. During the full-scale invasion, he tried to block the supply of weaponry and opposed Ukraine's accession to NATO. Therefore, Ukrainian diplomats had been preparing the president for a less-than-pleasant conversation before he left for Bulgaria.

Foreign Minister Mariya Gabriel met Zelenskyy. After that, he held talks with the Bulgarian government. Finally, he met Radev.

The Bulgarian public media broadcast the meeting live. The Bulgarian president said he did not consider it advisable to continue supplying Ukraine with weapons, as this would not resolve the "conflict".

"And if, God forbid, a tragedy happens [in your country], and you were in my place, and people with common values do not help you with weapons, what will you do? You will say: "Putin, take over the Bulgarian territories?" Zelenskyy replied.

In his statement, he also mentioned the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant. Radev used this as a clue to get out of an awkward situation. He offered to talk about energy and discuss "one offer". And then he pointed towards the camera and said, "Thank you, media". Like, switch it off.

The Ukrainian delegation did not understand what was happening. The journalists started to assemble, and the simultaneous interpreter had yet to explain Radev's last sentence. When Zelenskyy heard the translation, he grasped the situation and thanked the media. Radev didn't want the Ukrainian president to embarrass him on one of Bulgaria's most popular TV channels.

Bulgarians had different perceptions of the situation. Radev's former adviser, Alexander Marinov, who had worked with the secret services of communist Bulgaria, said that it was not the Bulgarian president who quarrelled with the Ukrainian president but the other way around. Atanas Atanasov, a member of parliament and head of the Democrats for Strong Bulgaria party, said: "The masks are off. Against the background of President Radev's position, who has clearly sided with Russia, it is clear why Bulgaria needs a regular government."

So what about the government? Bulgaria has not had one for almost a year because of the political crisis, and Radev appointed ministers. The previous government managed to secretly transfer weapons to Ukraine before losing power. In this way, members of the previous cabinet destroyed the classic image of "pro-Russian Bulgarians".

Ottomans, Germans, Communists

Whatever the relationship between Sofia and Moscow, the route from Bulgaria to Russia goes transiting through Ukraine. This is not only a metaphor but also a geographical fact. So, the Russian Empire's expansion into the Balkans was only possible with control over southern Ukraine.

At the end of the eighteenth century, the Russian Empire destroyed the Zaporizhzhian Cossacks and the Crimean Khanate and prepared to extend its influence to the southwest. The early nineteenth-century French publicist Frédéric Gaillardet described Russia's foreign policy goal: "to get as close to Constantinople as possible".

The instrument for achieving this is "to foment constant wars with the Turks". However, Gaillardet put these words into the mouth of the first Russian emperor, Peter. He allegedly bequeathed his heirs to do precisely that. Peter did not do this, but it described Russian foreign policy so accurately that this "testament" was accepted for a long time.

Step by step, the Russian Empire cut off more and more territory from the Ottomans, both in the west and the east. However, during the first half of the nineteenth century, the entire Balkan region remained under the influence of Istanbul. But even if there is no change on the map, there is some change in the minds of the educated Serbian, Greek, Romanian and Bulgarian elites. They wanted to free themselves from Ottoman rule, take power into their own hands and create nation-states.

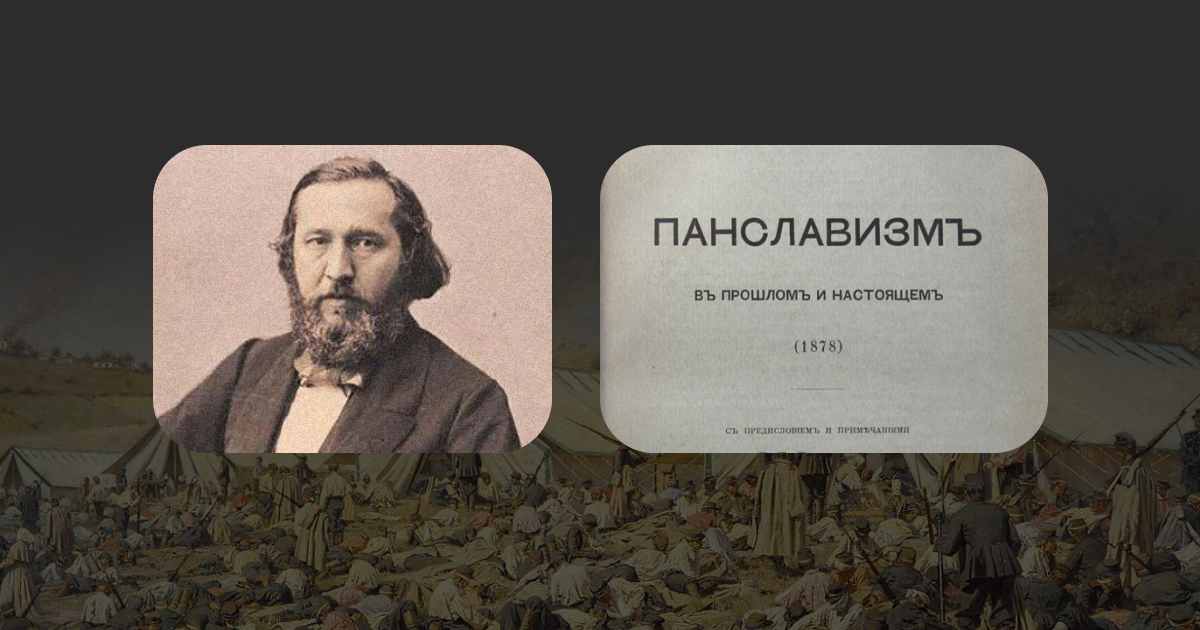

Meanwhile, alongside Expressionism, Pan-Slavism, an ideology that seeks to unite all Slavic peoples under the leadership of the Russian Tsar, was spreading in Russia. The texts of the leader of this movement, Konstantin Aksakov, are not that different from contemporary Russian propaganda: "Europe is on the wrong path, the United States is a country without people or history, and the rest of the world is 'in a state of savagery'. And Russia will save them all because it is Orthodox."

Most of the elites of the Balkan nations, including the Bulgarians, were also Orthodox. Here, their nationalism and Russian pan-Slavism were well matched, so during the nineteenth century, people from Bulgaria received education and other support in Russia. Some went to study in Moscow, and others confined themselves to Odesa University, the first university from Bulgaria to Russia.

But even at this stage, there are nuances in the history of Bulgarian-Russian cooperation. First of all, Pan-Slavism is primarily a conservative ideology. Not all Bulgarians believed that Russia's social system was fair. They embraced doctrines that sought to change this status quo. Therefore, the attitude of these Bulgarians towards the empire was not very favourable. Bulgarian literary critic Nikolay Aretov points out that Bulgarians who were educated in Russia hardly ever wrote about the empire for a Bulgarian audience.

Secondly, the Bulgarian national movement was not limited to the desire to form their own state. The Bulgarian clergy also wanted to achieve an independent church, which until then had been governed by Greece. The Russians had a negative attitude toward these ideas. Russian diplomats pushed the Ottomans to isolate the leaders of this movement in the monasteries of Athos.

The story of Archimandrite Joseph Sokolsky is far more absurd. During the confrontation with the Greek Church, he entered into a union with the Pope. This frightened the Russians so much that Joseph was lured onto a steamer sailing from Constantinople to Odesa. He was held in Ukraine until his death to prevent the church leader from influencing the situation in Bulgaria. Over time, the absurdity progressed.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, some Balkan nations had already achieved statehood. A series of revolutionary wars resulted in the emergence of Serbia, Greece, Romania, and Montenegro. However, uprisings on the Ottoman Empire's outskirts were almost constant in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1876, this happened in Bulgaria.

In suppressing the uprisings, the Ottomans engaged irregular armed groups that committed crimes against the Bulgarian population. Russia received a pretext for another war against the Ottomans — the protection of the Orthodox people. The Russian Empire defeated the Ottoman Empire, and a peace treaty was signed, according to which Bulgaria gained independence within borders larger than its present-day ones.

Western countries see this formation as a powerful state controlled by Russia that will change the balance of power in the Balkans. Therefore, they urge the Russians to limit their appetites. By the Berlin Congress of 1878 decision, Bulgaria became a constitutional monarchy within reduced borders, a vassal of the Ottoman Empire.

But where to get a monarch to the throne of a state with no royal dynasty? It was not the first time European countries deciding the fate of the former Ottoman territories had raised this question. The task was rather technical — finding a candidate to satisfy all countries.

In Germany, such candidates would be enough for another ten thrones because of the large number of families. Russia and the European countries chose Alexander of the Battenberg family for Bulgaria. His family was close to European monarchs, but Alexander was the nephew of Russian Emperor Alexander II. He also took part in the war in Bulgaria. The first ambassador of the empire to Bulgaria, Aleksandr Davydov, wrote to Foreign Minister Nikolay Giers in St Petersburg: "I believe that the best candidate, indeed, the only possible candidate, is Alexander von Battenberg." And so the German became the Bulgarian prince.

But nothing went as planned. Battenberg's advantage turned out to be his disadvantage: during the battles in Bulgaria, he saw the Russian army in action. "Every day, things happen that make your hair stand on end, and if I were to recount the bare facts simply, everyone around me would think that I was exaggerating as a supporter of the Turks," he wrote in a letter to his father.

He criticised the frivolity of the general staff, the disorder in the army and rear, and the constant plundering. So, his attitude towards the Russians was appropriate. After the war was won and Alexander was inaugurated as Minister of Defence, he was forced to welcome a Russian general. Hence, quarrels began almost immediately over minor details, such as how a Russian should address the prince.

Initially, the newly appointed monarch disliked both Russians and Bulgarians. He had little respect for the constitution and favoured the conservative party. The Bulgarians were unhappy that Russia had promised vast territories but failed to deliver. Alexander's popularity grew in 1885 when the prince supported the expansion of the borders through a coup in a neighbouring ethnically Bulgarian region that had not been included in the country at first. This meant the final deterioration of relations with the Russian Empire.

Therefore, the following year, pro-Russian officers staged a coup, in response to which Bulgarian officers and revolutionaries staged another coup in support of the prince. The German decided to abdicate himself to stop the political crisis. "After Russia expelled Alexander von Battenberg, it became clear that only the occupying tsarist forces could return Bulgaria to the Russian sphere of influence," writes historian Mikhail Rekun.

He believes the lack of coordination between Russian diplomats and other representatives in the Balkan countries caused the empire's defeat. Everyone did what they wanted, and they were rude and arrogant towards the Bulgarians. Despite the grand historical narrative of the great friendship between Bulgarians and Russians, the reality was somewhat different.

Over the next 30 years, the level of relations with Russia changed, but the first decade after the proclamation of the principality was pivotal. The empire failed to make Bulgaria its puppet.

The second time such an opportunity arose for Moscow was in 1944. Bulgaria took part in World War II on the side of Nazi Germany, so when Soviet troops approached the country, they had a reason to overthrow the regime. The country was headed by communists hiding in the Soviet Union for a long time from persecution by the Bulgarian monarchists. During the Cold War, Moscow considered Bulgaria the most loyal of all the countries in the socialist bloc. This image was so firmly entrenched that even in the 1990s, Bulgarian peasants continued to refer to their country as the "sixteenth republic of the USSR".

The country depended economically on trade ties with the USSR and other Warsaw Pact states — only 5% of Bulgarian exports went to other countries. Bulgaria traded with capitalist European countries less than any other Eastern European or Balkan state. In 1983, the communist leader Todor Zhivkov, who had led the country for 35 years, met with American members of Congress and joked that it was not the USSR that colonised us. Still, rather the other way around — we supplied them with technological products. They provided us with cheap raw materials. These jokes turned out badly for Bulgaria.

Bulgarians, Romanians, migrants

Zhivkov had a negative attitude toward perestroika in the USSR and would probably have been in charge of the country for just as many years if not for the collapse of the socialist bloc. After that, Bulgaria faced the issue of what kind of country it was and how it should develop.

After the fall of the authoritarian regime, its political landscape did not differ much from similar countries in Central and Eastern Europe: one party united centre-right reformers, and the other was the heir to the communist party. Like other countries in the region, Bulgaria chose Euro-Atlantic integration. However, it was more difficult for Bulgarians to implement because of the high level of dependence of the economy on ties that were, if not destroyed, then significantly damaged.

In 2004, Bulgaria joined NATO. This was preceded by its assistance to the United States in the Second Iraq War. Sofia wanted to demonstrate to Washington that it could be relied on, unlike Western European countries that were sceptical about the US invasion.

Joining NATO was also facilitated by Russia's inability to achieve its foreign policy goals. Moreover, at the level of ideas, the concept of "old and new Europe" by Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfeld became popular. He argued that Europe's centre of gravity was moving eastwards. However, Russia's return to the struggle for international power after 2008 changed how the US views Eastern Europe.

Bulgaria's relationship with the European Union has been more complicated. Although Bulgaria and Romania signed association agreements with the EU in 1993, they completed accession only in 2008, separately from most Eastern European countries. Immediately after accession, Bulgarians felt they had been granted "second-class membership" because they could not access visa-free travel in the Schengen area.

Fifteen years later, the situation remains the same. At the end of 2022, the European Council returned to this issue. The member states' interior ministers considered it as a package, meaning that an unfavourable decision on one country would lead to an unfavourable decision on another. Austria opposed Romania's accession to the Schengen area, which was enough to prevent Bulgaria from joining Schengen.

The Austrian government explained its stance by saying that Romanian smugglers use Bulgarian territory as a transit area, so the problem arises because of Romanian law enforcement and border guards. In addition, the Netherlands opposed Bulgaria's accession.

The feeling of second-class status persists to this day. It is also facilitated by Bulgaria's being the poorest country in the EU. Its GDP per capita has not yet reached half the average for EU member states.

Dr Dimitar Bechev, a visiting scholar at Carnegie Europe, explains in a comment to Svidomi: "Bulgarians have different opinions on why they feel they have a second-rate status. Nationalists blame Western elites and Brussels, while liberals blame Bulgarian politicians for not doing enough to integrate into the European Union."

This is not the only thing that divides Bulgarians today. Most support EU and NATO membership, but their political preferences differ. Therefore, a pro-European party could have enough votes to form a government.

Corrupt officials, reformers, diplomats

However, pro-European voters split between the two parties: GERB and Continue the Change and Democratic Bulgaria (CC-DB). The leader of GERB, Boyko Borisov, has been in politics for more than 20 years and has served as prime minister three times. He has been involved in several corruption scandals and simultaneously flirted with the EU, the US, and Russia.

Photos from his meeting with Putin in 2010, when the Bulgarian prime minister presented the then-Russian prime minister with a dog, are circulating on Bulgarian social media. "Because of this, the reformists from the CC-DB did not want to team up with GERB because it would have damaged their reputation," Bechev explains.

The previous government, led by CC-DB leader Kiril Petkov, which governed the country from December 2021 to August 2022, did not include GERB. Therefore, the reformers had to form a coalition of four parties, and when one of them left the government, the parliamentary opposition, led by GERB, voted to recall the government. However, Petkov's cabinet took the most crucial step in the relations between Ukraine and Bulgaria — the country secretly supplied Ukraine with 2.5 billion euros worth of shells.

"It is said that at the time, these supplies met 50% of Ukraine's needs, especially for 152mm shells," says Bechev, adding, "Radev, who usually opposes the supply of weapons to Ukraine, knew and kept silent.

At the same time, Bulgaria, like other European countries, continued trading with Russia in 2022. Imports of Russian goods reached their highest levels, even though Russia stopped supplying gas. This is most likely a record for the entire period since the collapse of the USSR. One can draw these conclusions from the data of the European Statistical Office and the UN trade database.

Bechev doubts the accuracy of these calculations. Indeed, the National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria, on the contrary, shows a decline. Bechev suggests that if there was any growth, it was most likely driven by purchases of Russian oil and oil products. However, diesel fuel is subsequently re-exported to other countries, including Ukraine.

Bechev draws attention to another circumstance: "In November 2022, the Bulgarian parliament united around the issue of providing weapons to Ukraine. "GERB and CC-DB voted for it together. It was a sign that they would cooperate." And eventually, they did: after the April 2023 elections, the two parties formed a government together.

However, a scandal hit Bulgarian-Ukrainian relations between November 2022 and April 2023. In December 2022, the President of Ukraine appointed Olesia Ilashchuk as Ukraine's Ambassador to Bulgaria. She has a field qualification but has never worked in diplomacy and had nothing to do with Bulgaria. The appointment of outsiders to ambassadorial posts is a common practice, but Ilashchuk had no experience in public administration.

Yevropeiska Pravda even demanded that the decision be cancelled, arguing that it damaged the fragile Ukrainian-Bulgarian relations. However, Bulgaria gave its agremann (consent) to Ilashchuk's appointment.

It is difficult to say whether the appointment has damaged relations. "I don't think she has become a well-known figure," says Bechev.

On June 26, the Bulgarian government approved a military aid package for Ukraine — this time publicly. Channels affiliated with the Presidential Office claimed that this resulted from Ilashchuk's work. However, GERB and CC-DB had supported the provision of weapons to Ukraine in the autumn before her appointment.

Risks ahead

This does not mean that Ukraine-Bulgaria relations will now move only in a positive direction. The recent elections resulted not only in the formation of a pro-European government. The pro-Russian opposition, the Revival Party, gained strength. While it did not have a single seat in parliament in 2021, it has gained the support of 13% of Bulgarians during the two years of political crisis. If the newly formed government fails to ensure stable governance, trust in the ruling parties will decline, and opposition projects will receive more votes.

This is possible because Bulgaria does have a latent pro-Russian electorate. However, we should not exaggerate. It also exists in Ukraine and other European countries. There are indeed episodes of cooperation with Russia in Bulgaria's history, and the grand narrative of "Slavic brothers" and "Orthodox civilisation" seeks to promote them as much as possible.

But there have also been plenty of conflicts in their relations. So, in this situation, the recipe for countering propaganda for Ukrainians remains the same as always: a balanced portrayal of the past rather than more propaganda in response.