Who populated Mariupol, and why is it considered multi-ethnic?

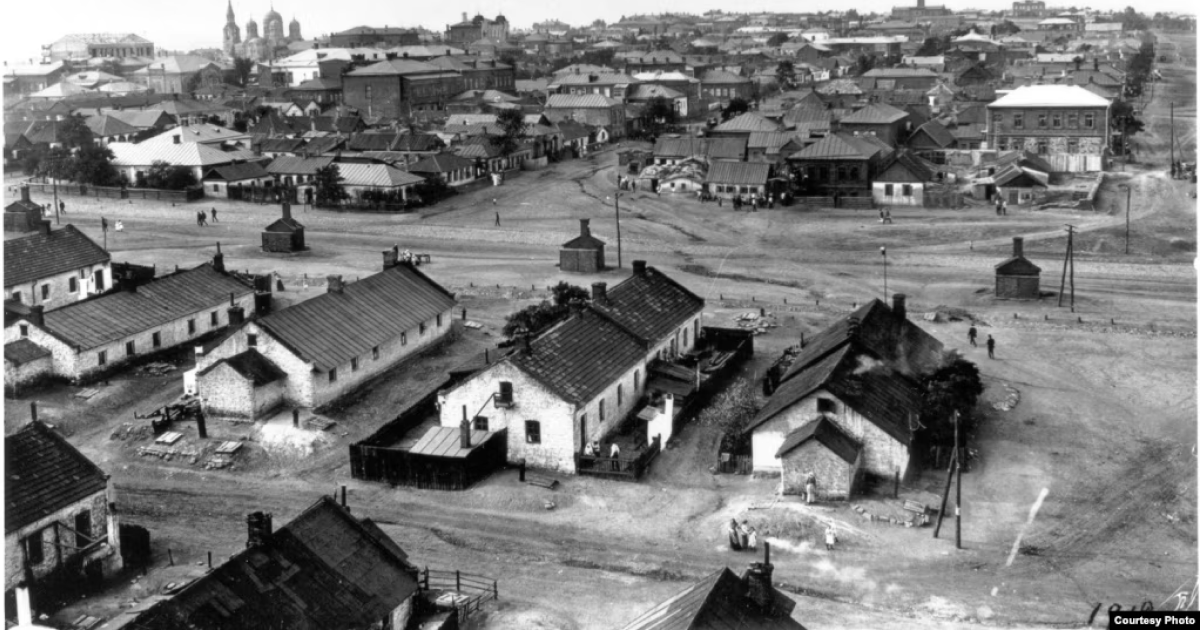

The official foundation of Mariupol is considered 1778 when the city was founded in connection with the relocation of Orthodox Greeks from Crimea (in what is known as the Emigration of Christians from the Crimea—ed.). This is how the city's multiethnic diversity was formed. The Soviet authorities promoted the narrative of 134 ethnic groups living in Mariupol, but is this true, and who has long enjoyed a mono-majority in the region?

Read the article about the history of the inhabitation and development of Mariupol and surrounding settlements, as well as the story of a Ukrainian-Greek woman who still preserves the historical heritage of her Greek ancestors in Mariupol.

Resettlement of the 'Mariupol Greeks’

At the end of the 18th century, the imperial government resettled the Greek-speaking and Tatar-speaking community from the Crimean Khanate to Nadazovia (northern Pryazovia, south of Ukraine—ed.), says Vadym Korobka, PhD in History, Associate Professor of History and Archaeology at Mariupol State University.

"The main sign of their unity was belonging to the Greek Orthodox Church. Based on legally secured privileges, the new settlers formed a confessional and social community, which in imperial legislation and historiography was called 'Mariupol Greeks'. It is obvious that the name 'Greeks' was confessional — the name of a religious group," explains Vadym Korobka.

He says that the genetic kinship of the descendants of the 'Mariupol Greeks' with the people who now make up most of the population of modern Greece and Cyprus requires scientific proof.

Larysa Yakubova, a PhD in History, explains that the first 20 villages around Mariupol were founded by deported Elenes and Tatars from Crimea (Qırım), who formed the basis of the Mariupol community, the so-called Greek district of Mariupol.

"Until the middle of the 19th century, Mariupol was a Greek mono-ethnic city. There were only a few Russian administrators sent by the Russian Empire. Most of the inhabitants of Mariupol were Mariupol Greek and the Turkic-speaking Urums (also called Graeco-Tatars), who came from various Crimean settlements. They spoke the Ruméika language (Rumaíica, from Greek: Ρωμαίικα — ed.). Linguists and historians consider it similar to the language of the Crimean Tatars,"

says historian Larysa Yakubova.

The industrial development of Pryazovia and the settlement of Europeans

The Greeks managed to maintain a mono-majority in Mariupol until the 20s of the 19th century. Later, however, the autocratic government of the Russian Empire allowed German colonists to settle there. As a result, many German colonies were established in the Mariupol district. They were separate from each other, formed by people from different regions of Europe and German lands with their own identities and peculiarities.

However, Ukrainians from the north of Slobozhanshchyna, right bank Ukraine, and Russians from the Don Army area settled there as well. Bulgarian villages and Jewish farming colonies also appeared.

According to Larysa Yakubova, the industrial development of Pryazovia and the territory of the future Donetsk Municipal Coal Basin began with the settlement of Russians and Ukrainians. Yuzivka (modern Donetsk — ed.) was founded and became a centre of the mining industry, with a railway to Mariupol and the convenience of shipping semi-finished iron ore across the sea.

"Foreigners built two of the largest metallurgical plants. They built an industrial centre on a concession basis and attracted specialists, including technicians, engineers, etc. They came to the city with their families," explains the historian.

This is how Europeans began to settle in and around Mariupol. But they were not the majority. However, their influence in the city was significant because they were the owners of businesses and the managers of workshops. This continued until the arrival of Soviet rule and the beginning of industrialisation in the 1930s.

The Soviet narrative of Mariupol's multi-ethnicity

Larysa Yakubova notes that Soviet historians promoted the narrative of 134 nationalities living in Mariupol. However, this is not true. No more than ten ethnic groups lived in the Mariupol area. This was more characteristic of the rural areas around Mariupol than of Mariupol itself.

She says there were representatives of different nationalities, no more than 30-40 people, so they were not ethnic groups but people who came alone or with their families.

"Rumours about diversity are greatly exaggerated. This is a journalistic stamp created during Stalinist modernisation, when they were actively working on the People's Friendship Concert, and later, the Soviet Union was supposed to be a common home for all ethnic groups without racism and chauvinism. Behind this stamp was a policy of Russification of Ukrainians, Greeks, Jews, Bulgarians and Germans from southern Ukraine," Yakubova explains.

"I am a Ukrainian Greek". The story of a Greek national movement activist

Oleksandra Protsenko-Pichadzhi is a descendant of the Haraman and Pichadzhi Ruméika families. Her mother's roots go back to the village of Chermalyk (Greek: Τσερμαλίκ — ed.), founded in 1780 by Greeks deported from Crimea, and her father's are from Nova Karakuba, which was called Krasna Poliana in Soviet times.

"Since childhood, I have heard that we are Greeks from Crimea, and the stories about the resettlement were that people went by force, and on the way, they suffered many diseases. Many Greeks never reached their new homeland,"

tells Svidomi Oleksandra Protsenko-Pichadzhi, Honorary Chairman of the Federation of Greek Societies of Ukraine and Chairman of the Union of Greeks of Ukraine in Greece.

Before the outbreak of World War II, her family lived in Mariupol. On the eve of the Nazi invasion, they settled in the village of Kyrylivka in the then Volodarskyi district, now the Kalchyk community of the Mariupol district. The woman moved to Mariupol in 1968 and lived there until March 17, 2022.

"I grew up in a Greek village, in a Greek environment. In our house, we secretly kept a book of poems by the Ruméika poet Georgis Kostoprav called Kalimera, zisimo (Καλημέρα, ζήσιμο! Hello, life! — ed.). I am a Ukrainian Greek, in my understanding.

My strong identity and sense of duty to my native people led me to the Ethnic Movement of Greeks of Pryazovia, to which I have dedicated more than thirty years of my life. It is in my blood and my soul," says Oleksandra Protsenko-Pichadzhi.

Oleksandra's family's stories from 1778-1780 were told by her grandmother, Aniuta because she remembered the stories of her own grandmother, who witnessed the events.

From 1995 to 2023, she headed the Federation of Greek Societies of Ukraine, an ethno-cultural organisation that united all Greeks in Ukraine. Every two years, the organisation held the International Festival of Greek Culture Mega Yorti, which means Great Feast, the Tamara Katsa Greek Song Festival, which featured songs in Ruméika and Uruma, and the Greek Art Olympiad.

"We kept in touch with our ancestral homeland through health programmes for children, learning New Greek, and at the same time, we were committed to preserving our own identity," says Oleksandra Protsenko-Pichadzhi.

The Federation of Greek Societies of Ukraine supported folk groups in Greek villages. Greek artists also performed rituals, such as a traditional Greek wedding. Oleksandra is fluent in Ruméika. The woman also preserves the culture of her ancestors through Greek cuisine.

"I keep our culture alive in my family through our incredibly delicious dishes: chiri-chiri (chebureks), shumush (a pie with meat and pumpkin), fluto (a twisted pie), and salmaida," says the Chairman of the Federation of Greek Societies of Ukraine.

In Mariupol, there is the building of the Cultural Centre of the Federation of Greek Societies of Ukraine, the Greek Medical Centre, which assisted residents of Greek settlements, and the building of another cultural centre, Meotyda, which hosted concerts and a Sunday school for learning the language and traditions.

According to the activist, the Greeks of Mariupol had opportunities to meet all their educational, social, and cultural needs. The infrastructure was well-developed. They had absolutely everything.

"I want to tell the whole world that Mariupol is the heart of the Greeks in Ukraine! Since its foundation in 1780. Mariupol was settled, built and developed by Greeks," says Oleksandra Protsenko-Pichadzhi.