"We have to make society emancipated during the war to come out not only as winners but also as equals." — Tamara Zlobina

Tamara Zlobina is a PhD in Philosophy and the head of the expert resource Gender in Detail. She works with the topics of civil society development and innovative outlook, gender equality, feminism, and contemporary art.

Svidomi talked to Tamara Zlobina about Ukrainian feminism, how it was born, its goals today, and how feminism can be helpful to men.

In Ukraine, the feminist movement originated in the late nineteenth century, but later the USSR promoted the illusion of equality. How did this affect the development of this movement in Ukraine?

The first wave of feminism in Ukraine emerged simultaneously with feminism in Western countries, i.e. at the end of the nineteenth century. In 1884, Nataliia Kobrynska founded the Society of Russian Women, the first feminist organisation in Ukraine.

We have every right to call it a feminist organisation because half a century later, a new organisation, the Union of Ukrainian Women, which operated in interwar Poland and included western Ukraine at the time, held a feminist congress in honour of the 50th anniversary of the feminist movement in Ukraine. The issues that feminists were working on in Ukraine at that time were the same as those that feminists were working on in other countries: equal voting rights, the right to education and work, and economic rights.

Today's women may think that equal rights are a natural state of affairs and that it has always been so. Yet it is not: 100 years ago, women fought, handcuffed themselves to railroads, and clashed with the police to achieve this. But we have been made to forget the unique history of the women's rights struggle because it was silenced in the Soviet Union.

It is essential to understand that Ukraine was part of different empires. The Russian Empire also had a powerful movement for women's rights. In 1917, the First World War was going on, Russia was exhausted, and the economy had huge problems.

Then, in the old style, at the end of February or in the new style, on March 8, women, mostly workers, in St. Petersburg went out in a mass demonstration demanding peace, bread, and women's suffrage. It was a massive demonstration that led to the events known as the February Revolution.

After that, women continued to demand equal voting rights, and they received them by a decree of the Provisional Government. By the end of spring, they were already participating in elections for city councils. And only a few months later, the October Revolution took place, resulting in the Bolsheviks coming to power. However, in the Soviet Union, all this was hushed up, and the official ideology claimed that the Bolsheviks "gave women rights."

And when Soviet schools talked about Lesia Ukrainka, Olha Kobylyanska, or Natalia Kobrynska, first-wave feminists, the word feminism was never used. Instead, they were called socialists and told that they fought for the rights of peasants and workers, but they were silent about the fact that they fought for women's rights.

What happened to women's rights in the Soviet Union?

The first decade of Soviet rule, the 1920s and 30s, was marked by gender emancipation. It had a specific goal: women were to be equal workers and builders of communism. For this purpose, women had to be relieved of household chores.

The Bolsheviks came up with a gender contract between the state and a working mother: the state created kindergartens, canteens, and laundries to reduce the burden on women. It also introduced mass education for boys and girls. These were progressive moments.

With Stalin's rise to power, there was a conservative turn toward traditional gender orders and stereotypes. This turn intensified after World War II due to the vast population losses. Women were to restore these losses, so in the 1950s, the cult of the mother spread in the USSR.

However, all this happened in a somewhat hypocritical way. The maternity leave was short, and only in the 1980s an additional unpaid parental leave of 1.5 years was introduced (it was extended to 3 years only in 1989). That is, a woman had to give birth to more children, put them in a nursery, and go to work at the factory. So it was a double exploitation.

In the 1960s, the USSR announced that the "women's issue" (i.e., the issue of women's equality) in the Soviet Union was finally resolved. This closed any possibility for discussion. However, rape, harassment, domestic violence, unequal division of labour, a glass ceiling for women, and stereotypes about women in education, the labour market, and culture remained. Still, no one could discuss them.

In the 1990s, Ukrainian feminists had to work hard to get rid of the influence of the Soviet Union, this illusion of equality imposed by a totalitarian regime. At a time when the third wave of feminism is beginning in the West, we are also starting our third wave of feminism in sync with the second.

But unlike Western feminists, who could rely on the experience of their predecessors, Ukrainian women did not have this opportunity. So now we are rediscovering the feminist history of Ukraine.

What is Ukrainian feminism today? What do feminists want to convey?

First, we discuss justice, safety, and efficiency because gender stereotypes and prejudices hinder development.

A familiar example is labour education classes at school. Boys are taught one job, and girls another. Again, this results from gender stereotypes that do not consider people's talents.

A boy may be a talented cook, makeup artist, or designer, but he will not receive this knowledge. Likewise, a girl may have a talent for carpentry and could become a furniture designer, and she needs to acquire these skills.

Because of gender stereotypes, children will be guided in the opposite direction to their talents, and people will waste time and resources overcoming prejudice. Or they will follow the lead of others and eventually realise at the age of 30 that they have not lived their own life and that this "not manly" or "not womanly" thing is a matter of their life.

Society will be better off if talented people don't spend additional resources fighting outdated prejudices and the obstacles these prejudices create.

It is the essential thing that feminists talk about.

On top of this base, we can layer various social problems such as sexual harassment, domestic violence, the glass ceiling, bias against women in leadership, sexism, stereotypes, etc., because they all lead to a loss of personal and social resources.

Feminists want to make the world happier, safer, and fairer through equality and impartiality.

What harmful labels about Ukrainian feminism prevail in society, and how to combat them?

Why are people xenophobic, racist, or sexist? It has a hidden benefit — such people consider themselves better than others just because they belong to a specific group. You don't need to have any achievements to feel better about yourself. It is challenging to fight such a mechanism of psychological compensation for one's failures with rational arguments.

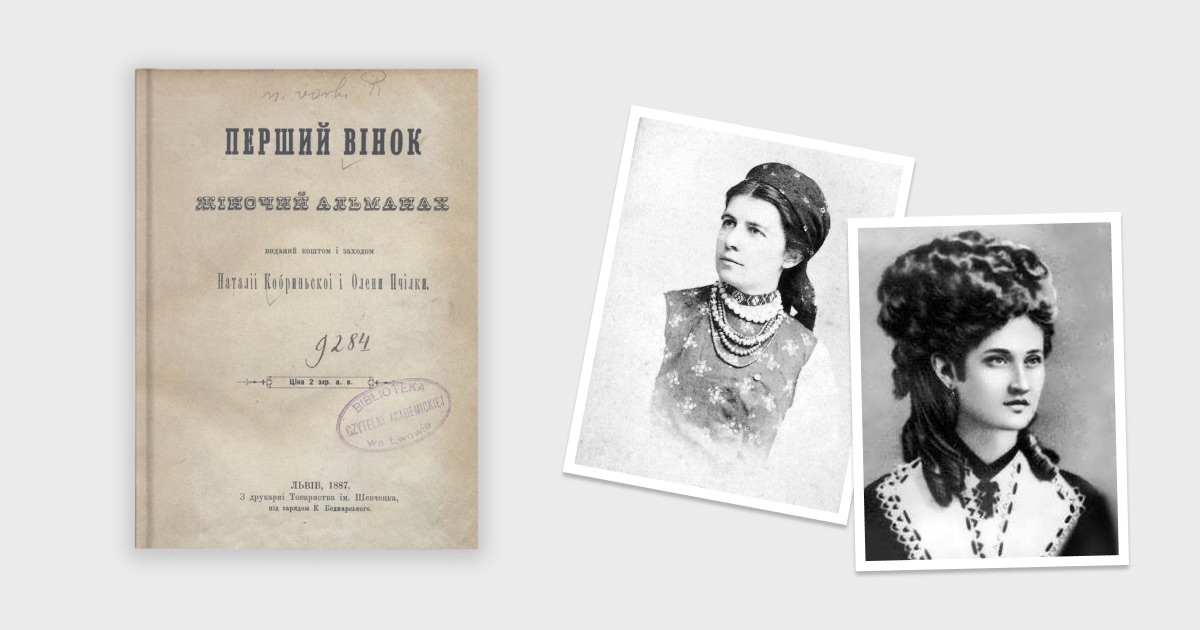

Still, it is necessary to convey the facts. The first point is that feminism is a Western phenomenon imposed on Ukraine for grants. We take a history textbook and look for the grants Nataliia Kobrynska received when she founded the Society of Russian Women. Together with Olena Pchilka, they invested their money to publish a women's literary almanac called The First Wreath. What grants did Lesia Ukrainka, Olha Kobylianska, and Milena Rudnytska receive? Even now, feminism is a mass movement of women for their rights. Most people support it voluntarily — no one pays for their worldview.

Another common misconception is that women already have all the rights, and feminists are inventing something. In response, we can cite statistics on domestic violence, rape, harassment, and the low level of women's representation in government, leadership positions, and as experts in the media. But I will return to the example of labour training: we still make life difficult for talented people because of gender stereotypes, so we have not yet reached a state where there is an equal attitude towards people regardless of their gender, age, nationality, or race.

Can a man be a feminist, or is it something like a "Russian liberal"?

It is a classic debate in feminism: can men be called feminists or only profeminists? The answer to this question depends on how we see feminism. Feminism is a movement for rights and a worldview.

If we see feminism only as a movement for women's rights, then this movement should be led by women. In this case, men can be allies, i.e., profeminists. On the other hand, if feminism is a worldview on which society should be based, then men can also be feminists.

I perceive feminism primarily as a worldview project of building the future, so I call men feminists. In my opinion, building the future together is just as important as fighting for specific rights.

How does feminism help men today, and can it benefit them?

It's a slippery slope because it's not feminism's job to help men. It is still a movement for women's rights. But men benefit from it because feminism creates an equal and productive society.

The fight for women's rights positively impacts men because it makes the world safer. For example, women suffer from violence, including on the streets. As a result, they are afraid to go home in the evening. For this purpose, feminist urbanism suggests making city spaces safer. It means the absence of bushes, piles of abandoned kiosks, the need for bright lighting, video cameras, and proper police work.

Organising the street this way will also be much safer for men to get home. It applies to all manifestations of feminism because, in the end, not only women but also men benefit from it.

Discussions about March 8 are ongoing. Unfortunately, there is no clear understanding of what kind of day it is in Ukraine, and there is still a perception that it is a holiday of beauty and spring. How to work with such an opinion?

Feminists have almost dealt with this problem. I was sorry to see the bill to abolish March 8. We are one step away from changing the Soviet traditions of celebration.

In the 1930s, postcards for March 8 depicted women as equal workers; in the 1950s, they depicted the cult of the mother; and in the 1970s and 1980s, it was spring, beauty, and snowdrops. It is Soviet sexism.

In the 70s and 80s, there was a shortage of consumer goods in the Soviet Union-not enough clothes, not enough food for everyone, and you had to stand in long lines just to get bread. And in such a gloomy world, people had two bright holidays-February 23 for men and March 8 for women. My older friends told me that on March 8, they had a tradition of sleeping late while their husbands and sons made breakfast and washed the dishes. On all other days of the year, women did this. Suppose you live in a scarcity society and have one lovely holiday yearly. In that case, it becomes essential — these historical circumstances greatly influenced the traditions of celebrating March 8 in independent Ukraine, not their stability and duration.

Feminists fought against this interpretation. In 2006-2007, there were the first street actions. Since 2011, feminist marches have been organised in Kyiv. In 2021, the rally in Kyiv gathered more than four thousand people, and there were also actions in many other cities.

I remember how in 2011, the media did not know how to talk about it. At that time, journalists had a breakdown of consciousness about who these people were, what kind of women they were, why they didn't want flowers, and what they were doing. In 10 years, this has changed, and the Ukrainian media is now well aware that March 8 is the International Day for Women's Rights and International Peace.

The media talks about it and shows demonstrations. In 2022, we monitored the pages of government agencies, where they usually congratulate on the "day of spring and beauty," but last year, it was different. Various law enforcement agencies, border guards or the Security Service wrote emancipatory posts and thanked the women employees for protecting Ukraine.

We were one step away from changing meanings, but then some members of parliament came out of nowhere and said there had never been mass feminist actions on March 8 in Ukraine. So I have only one question: where have you been these ten years?

We are returning to the fact that the feminist history of Ukraine has been erased. But we have to defend our roots because we have a proud history. If you read Lesya Ukrainka's works, they are more emancipatory than the works of the British feminist icon Virginia Woolf.

And March 8 is a good day to talk about this — about the traditions of feminism in Ukraine, about the modern demands of women.

The full-scale war has demonstrated how certain areas are adapted only for men, for example, the army, which still does not have a female uniform. What other problems do women face?

The issue of the female form has been raised for a decade. In Kharkiv, there is a Museum of Women's and Gender History, where there is an exhibit such as a tie pin from a ceremonial military uniform with the coat of arms of Ukraine. Women are forced to wear the coat of arms of Ukraine upside down because the women's shirt is buttoned on the other side. It is an anecdotal example because the clasp for a woman's shirt could be made to the other side (although this makes no practical sense), but the pin could not. And when we talk about combat conditions, this is a severe problem. It is difficult to fight when you don't have the right size shoes or bulletproof vest.

There is a widespread problem of domestic sexism. Previously, women could not hold combat positions in the army, and those women in combat positions were recorded in documents as seamstresses or cooks. It complicated their access to social benefits and career advancement. This discriminatory provision was abolished a few years ago thanks to female servicewomen's activism. For more details on women's problems in the Armed Forces and progress in solving them, see the study on Gender in Detail.

However, there are still many cases where commanders do not want to hire women.

Servicewomen say that in a new unit, they have to reassert themselves, explain that they are not a sweetheart or a sexual object and that they are professionals who have the right to participate in combat and do not need to be protected. It is also exhausting.

Last May, you criticised Western feminists who signed open letters calling for not giving Ukraine weapons. Has their opinion changed now?

At the beginning of the full-scale invasion, there were many stereotypes in the Western feminist movement. But thanks to the activities of Ukrainian feminists abroad and their discussions, the approach is changing. And it's important to emphasise that Ukrainian women are not the first to discuss this. For example, Kurdish feminists, who have a similar to ours experience of fighting for freedom, have also started talking about these problems in Western feminism: like us, they talk about the right to self-defence, that a defensive war is a matter for the whole society, not some kind of "masculine games," and that women can be active participants in these processes.

From history, we know that after this period of struggle, when women were involved because they were needed, they were tried to be sent back to their usual roles. It is the case of Olena Stepaniv, the first female officer in the world. After the end of the First World War, some intellectuals wrote plays about how she fought, but in their opinion, she should have returned to her feminine nature.

We also risk a conservative turn in society after the war, and they will try to push women back to their old positions. There are alarm bells — right-wing radicals with aggressive rhetoric and ideas to ban abortion "to restore the birth rate." It cannot be allowed. Women are the builders of the country. They do not help men to defend Ukraine — they defend Ukraine together with men. We must emphasise this and increase the representation of women in the media as experts in government and leadership positions.

We have to make our society more emancipated right now, during the war, to win as a democratic, equal society.