War for Culture: How Russians Are Returning to World Stages and Festivals

February 2022. Russian missiles rained down on Ukrainian cities — Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odesa, Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Chernihiv, Mykolaiv, and Dnipro. In response, cultural figures worldwide united in solidarity with Ukraine. Organisers of film festivals, music concerts, and book fairs severed ties with Russian artists and institutions.

At the time, Crimea and parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions had already endured eight years of Russian occupation. However, the full-scale invasion in 2022 seemed to signal a turning point: the isolation of Russian culture on the global stage appeared inevitable.

December 2024. Two years into the full-scale war, Russian artists quietly find their way back to international stages, film festivals, and cultural events, often aided by organisers eager to separate art from politics. Festivals like Toronto’s and institutions such as the Frankfurt Book Fair have started welcoming select Russian artists under the belief that “art should be judged by its substance, not its origin.” For many, public condemnation of Putin’s war is enough to unlock invitations to prestigious venues like the Bavarian State Opera — or even earn nominations for global honours like the Nobel Peace Prize.

Svidomi investigates how Russian culture is re-entering the global cultural space, even as Russia’s war against Ukraine rages on.

"Deaf" Russians at War

In November 2024, Tallinn hosted the Dark Nights Film Festival, one of the largest in Northern Europe, screening more than 500 films each year.

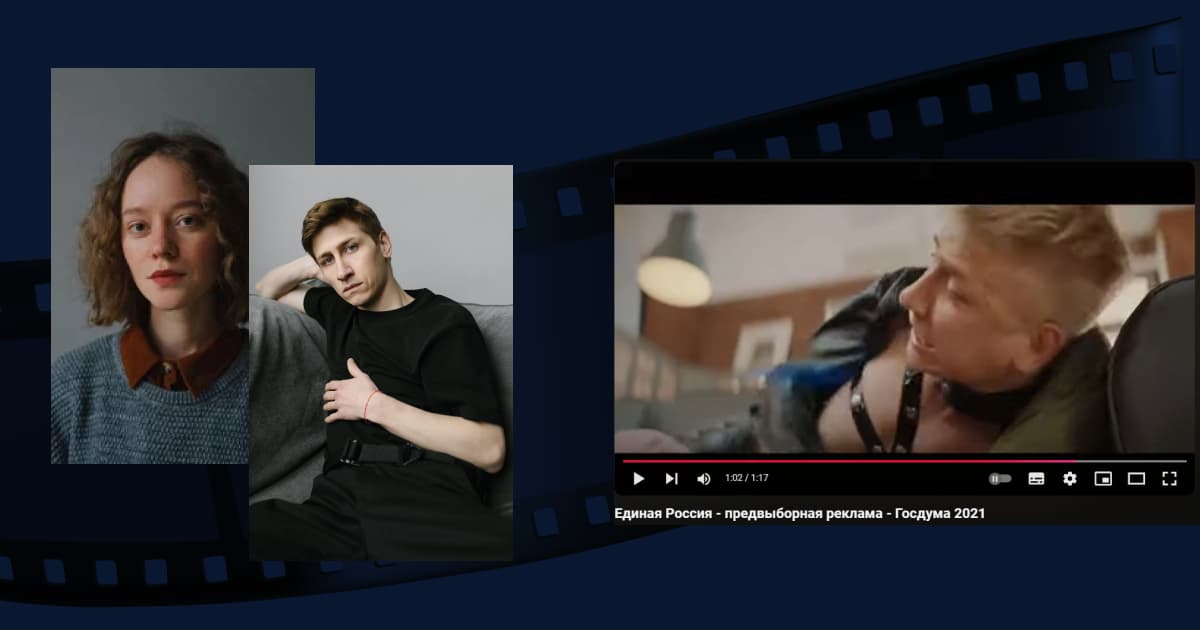

This year’s program featured Deaf Lovers, a film by Russian director Boris Guts. The story centres on two people who meet in Istanbul, fall in love, and face the challenges of emigration together—except he is Russian and she is Ukrainian. “And somewhere back home, there is a war going on,” reads the film's description.

The Ukrainian character, Sonia, is portrayed by Russian actress Anastasia Shemyakina. Meanwhile, Russian actor Daniil Gazizullin, who plays the Russian Danya, starred in a 2021 campaign video for Vladimir Putin's United Russia party.

Initially, Deaf Lovers was included in the “Stand with Ukraine” program. However, following public backlash, the film was removed from the program but remained part of the festival. In response, Ukrainian filmmakers and cultural activists penned an open letter to the festival organizers, urging them to remove the film entirely. The letter was signed by directors Oksana Karpovych, Pavlo Ostrikov, Taras Tomenko, producers Daria Bassel, Pylyp Illienko, Volodymyr and Anna Yatsenko, and the Ukrainian Institute.

“Given the love story between a 'Ukrainian girl and a guy from Russia' presented in the film, whose sympathy is emphasized even in the festival trailer, where the 'guy from Russia' complains about being tired of war, we can infer that the deaths of Ukrainian civilians, killed by specific Russian war criminals, are used instrumentally in the background of a narrative about premature reconciliation. This illustrates the same thesis about 'dirt,' pushing ethical boundaries to extremes,” the statement reads.

Despite the public statement from Ukrainian filmmakers and the media attention surrounding the film, Deaf Lovers was still screened at the festival. “It is in the program because it is artistically and content-wise very sharp, and it allows us to discuss current issues,” said Tiina Lokk, the founder and director of the Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival (PÖFF).

Mariia Ponomariova, a Ukrainian-Dutch director and producer, and a member of both the Ukrainian and European Film Academies, believes the situation surrounding Deaf Lovers reflects a broader issue with Russian cinema. Russian films have long had a prominent presence on global platforms, film festivals, and the international film market.

“When we talk about film festivals, the people organizing them are the ones who provide platforms for certain narratives. For me, this situation with Deaf Lovers shows how difficult it is to accept criticism from people who haven't seen the film. It’s as though, if I haven’t seen the film and I’m criticizing it, I’m violating a cultural contract where one can only critique a work of art based on its content, not its already problematic form of existence,” she says, explaining why the festival organizers refused to remove the film from the program.

Mariia Ponomariova was also among the Ukrainian filmmakers who publicly criticized the screening of Deaf Lovers.

“For me, the appearance and screening of this film are more significant than its content. Besides being a director and film producer, I work at film festivals. I understand that a film festival is a large institution that doesn't want to remove a film from its program, as it involves months of negotiations, a copy of the film, and significant work that they don't want to undo. So, it is difficult for a festival to acknowledge after the fact that it not only gave a platform to a Russian director but also validated his decision to cast a Russian actress as a Ukrainian woman. We must also consider the broader context: the director of this film lived in Russia for years, was a cultural figure there, and is now trying to position himself on the 'right side of history' without acknowledging his responsibility for his involvement in Russian politics and the war—this speaks volumes to me,” says Mariia Ponomariova.

Although Deaf Lovers was directed by a Russian filmmaker, it is officially represented by Estonia and Serbia. Another film from this year, Russians at War, directed by Russian filmmaker Anastasia Trofimova, is officially represented by Canada and France. It was shown at the Venice Film Festival and TIFF in Canada, where protests even erupted against its screening.

Russians at War is a documentary that depicts Russian volunteer soldiers participating in Russia's aggression against Ukraine. Trofimova claims she made the film “without accreditation from the Russian Ministry of Defense” and “at great personal risk.” The director wanted to showcase the Russian military “from their point of view, not from the Ukrainian or Western perspective.” She considers the film to be “anti-war.”

Anastasia Trofimova previously worked for Russia Today, creating documentaries about Syria and Africa. In 2023, she wrote an obituary on her Facebook profile for Kirill Romanovsky, a Russian propagandist and close associate of Yevgeny Prigozhin. The Toronto Film Festival, however, does not mention Trofimova’s past work with Russia Today or her connections to Romanovsky.

Russians at War received funding from various organizations, including the Canada Media Fund, which allocated approximately 340 thousand Canadian dollars. This raised concerns for Canada’s Deputy Prime Minister, Chrystia Freeland, who expressed dismay over Canadian tax dollars being spent on the film.

“This is a war of Russian aggression, a war where Russia violates international law and commits war crimes. Good and evil are very clear in this war. Ukrainians are fighting for their sovereignty and democracy around the world,” said Chrystia Freeland.

Although Russians at War did not premiere at the Toronto Film Festival, it remained in the program. However, following the publicity, Canadian television station TVO decided to withdraw the film from airing.

But the story of Russians at War doesn’t end there. The film was also screened at the Windsor Film Festival in Canada, where it was nominated for the Best Canadian Documentary Award. The Ukrainian-Canadian film Intercepted, directed by Oksana Karpovych, was also scheduled to be shown at the festival. However, after learning that Russians at War would be featured alongside their film, the Intercepted team withdrew their submission. Despite this, Russians at War remained in the festival program.

The fact Russians at War being produced in Canada and France highlights a broader trend in global cinema. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has led many film festivals and markets to stop accepting Russian-made films. However, they continue to collaborate with individual Russian filmmakers.

“It’s a workaround,” says Maria Ponomaryova. “Partners say to Russians: ‘We used to cooperate with you, but now it’s not a good idea to do so publicly. Cooperation is still possible, but we’ll look for other, less direct ways.’ Filmmakers, mostly from the West, believe supporting 'good Russians' is a kind of forbidden game. They don’t engage in any introspection. Meanwhile, Russians are very skilled at self-victimization, portraying themselves as people who had to leave their own country. This vulnerability garners sympathy, and Russian filmmakers take advantage of long-established contacts to get support, as they’ve been a fixture in the global film market for years.”

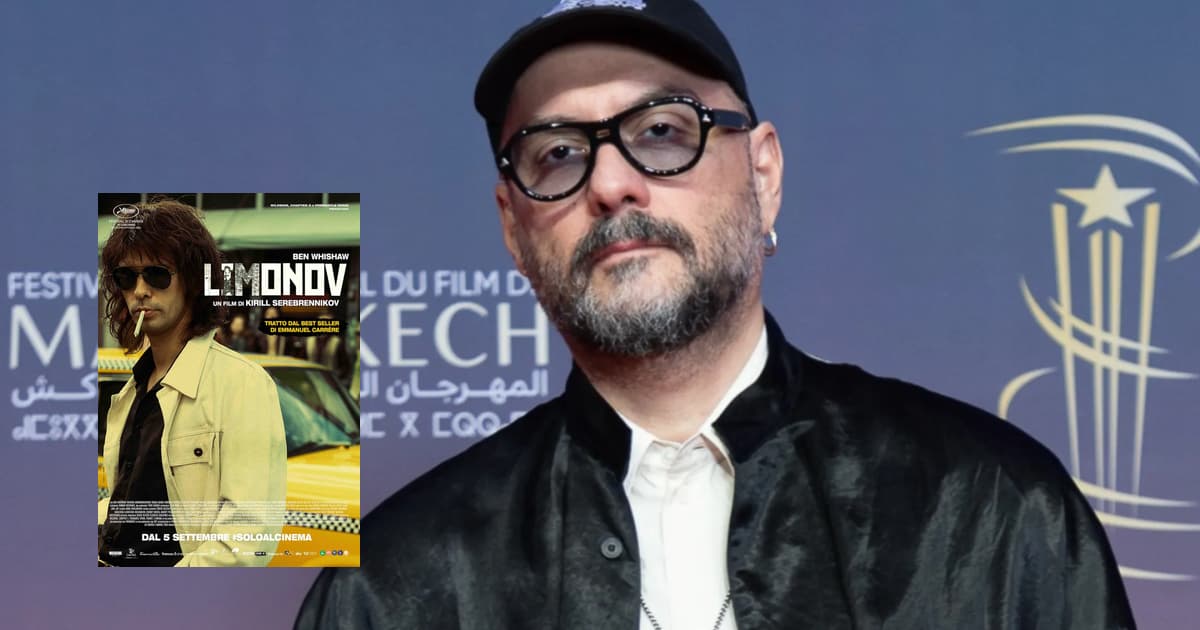

The best example of this phenomenon is Russian director Kirill Serebrennikov. In 2022, he left Russia, ostensibly to protest the country’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, despite the war having begun in 2014 with the occupation of Crimea. Serebrennikov was quickly allowed to participate in the Cannes Film Festival with his film Tchaikovsky’s Wife. During a press conference, he called for the lifting of sanctions against Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich and support for the families of Russian soldiers, claiming they had lost their “income.”

Ukrainian filmmaker Iryna Tsilyk criticized Kirill Serebrennikov for his statements, writing, “This is just one piece of the puzzle that shapes the image of the director, presented by the festival and many journalists as a ‘dissident.’”

In 2024, Serebrennikov presented his new film at the Cannes Film Festival, Limonov: The Ballad. This film, co-produced by France, Spain, and Italy, stars British actor Ben Whishaw in the title role. It portrays Eduard Limonov as a dissident who fled the USSR for refusing to cooperate with the KGB. Limonov, who founded the National Bolshevik Party, sought to combine the ideologies of Nazism and Bolshevism.

In 1999, the Security Service of Ukraine declared Limonov persona non grata, banning him from entering the country. He had openly opposed Ukraine’s independence and advocated for the annexation of the Donetsk, Luhansk, Kharkiv, Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, Mykolaiv, and Odesa regions. Limonov considered Crimea (Qırım) part of Russia long before its occupation and promoted imperialist views on Ukraine.

“The story of the movie about Limonov, especially in the Western European world, is presented as a story about a politician. He had certain views, and he did not like Ukraine. A society that considers itself democratic and has not experienced genocide fails to recognize that this biopic celebrates damaging narratives. This representation is not about them. At a workshop in Estonia in 2022, our French colleagues told us, ‘The Russians did you harm, and you are protesting. But why doesn’t anyone protest against movies about the mafia? They killed a lot of people too.’ There is still no understanding that this is more than just a ‘movie about a thief who, like all of us, even lived and loved.’ This normalization of someone with his views in the public space passively promotes these harmful narratives,” says Maria Ponomaryova.

Svidomi reached out to the organizers of the Tallinn Dark Nights Film Festival to inquire about their position on the screening of Deaf Lovers, but as of the time of publication, no response was received.

Similarly, Svidomi contacted the organizers of the Windsor Film Festival in Canada to clarify their stance on the nomination of Russians at War and their communication with the Peaceful People team. However, as of the time of publication, no response had been received.

The "Neutral" Stance of Book Publishers

In 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, prompting various book institutions to sever ties with Russian publishers, writers, and cultural organizations.

One prominent example was the Frankfurt Book Fair, one of the world's largest and oldest book markets. That year, the fair's organizers condemned Russia's actions, issuing a strong statement:

"The Frankfurt Book Fair is suspending cooperation with the Russian state institutions in charge of organizing the Russian collective stand at Frankfurter Buchmesse. The Frankfurt Book Fair assures the Ukrainian publishers’ associations of its full support,” the statement reads.

Ukraine participated in the 2022 Frankfurt Book Fair with the motto “Perseverance in Persistence.” A total of 46 Ukrainian publishers showcased their work at the event.

The Ukrainian stand at the 2022 Frankfurt Book Fair drew significant attention. Visitors engaged with speeches by Ukrainian writers and poets, including Serhii Zhadan, Stanislav Aseiev, Oksana Zabuzhko, Yuliia "Taira" Paievska, and Olesia Yaremchuk. The stand showcased Ukrainian books translated into German and other languages, using literature as a platform to spotlight the war and highlight Russia's war crimes.

2024. Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine continues. However, from October 16 to 20, 2024, five Russian publishers attended the Frankfurt Book Fair—the first such presence since 2022. These publishers did not represent Russia officially, as no Russian national stand was present, but rather participated as independent entities. They claimed a “neutral” stance.

Among the attendees was Eskmo, the largest Russian publishing house, holding 25% of the Russian market and publishing over 800,000 copies annually. Its catalog included books promoting anti-Ukrainian narratives, propaganda of the “Russian world,” and glorification of Russian law enforcement and military institutions.

In addition to Eskmo, other participants included A Walk through History, Samokat Publishing House LLC, Phoenix LLC, and Polyandria Print LLC.

The participation of Russian publishers sparked outrage among Ukrainian publishing representatives. Viktor Kruhlov, CEO of the Ranok publishing house, openly criticized the Frankfurt Book Fair organizers for allowing Eksmo to participate.

The Ukrainian Book Institute, which organized Ukraine's stand at the Frankfurt Book Fair, sought an explanation from the fair’s organizers regarding the admission of Russian publishers. On October 18, a group of Ukrainian publishers staged a protest near Eskmo’s stand, expressing their disapproval of its presence.

The organizers clarified their stance, stating that they would not "register the Russian national stand at the Frankfurt Book Fair" until the war in Ukraine ended. However, they allowed individual Russian publishers to participate and exhibit their books as long as they complied with German law.

Following public outcry and protests led by Ukrainian publishers, Eskmo closed its stand on October 19.

Nataliia Miroshnyk, head of the foreign economic activity department at the Ukrainian publishing house Vivat, criticized the lack of prior communication from the fair organizers. She revealed that Ukrainian participants were not informed in advance about the involvement of Russian publishers.

“We had a very tight schedule of meetings with our partners, so we didn’t have enough time for anything else. But we were also unpleasantly surprised that Russian publishing houses registered in Russia and those registered in European countries were given space to continue their cultural expansion. Eventually, this gained publicity, and on Friday, Eskmo closed their stand,” Miroshnyk explained, describing the communication between the organizers and the Ukrainian Book Institute regarding the situation.

The participation of Russian publishers in the Frankfurt Book Fair is no coincidence. Russia has long recognized the value of “soft power diplomacy,” particularly through cultural channels. In March 2022, the CEO of the Russian publishing house Eksmo, Yevgeny Kapyev, publicly appealed to foreign publishers and international book fairs to reconsider their boycott of Russian publishers, writers, and books.

“Let’s think together about how we can help make our world a better place. Our tomorrow depends on all of us today: will we build walls or bridges?” Kapyev wrote in an open letter.

He also urged foreign publishers not to block the sale of translation rights to Russian publishers, arguing that such actions would deprive Russians of access to foreign literature and potentially "reduce mutual understanding between countries."

Russian publishing houses have historically played a significant role in Ukraine’s book market. Even though imports of Russian books were eventually restricted, Russian publishers found ways to maintain influence by acquiring publishing houses in Ukraine and producing books in Russian. In 2013, Russian-language books dominated 75% of Ukraine’s book market. By 2021, just before the full-scale invasion, they still accounted for 50%.

This dominance enabled Russian publishers to swiftly produce Russian-language translations of foreign books for the Ukrainian market, as they held the rights to translate into Russian. In contrast, Ukrainian publishers often faced lengthy negotiations to secure translation rights into Ukrainian. This delay made it challenging for Ukrainian-language books to compete with their Russian-language counterparts.

Foreign publishers are usually interested in selling rights to as many countries as possible. Beyond the financial aspect, it’s also a matter of prestige. Typically, translation rights are sold for a specific language, and Russia hasn’t shown much interest in acquiring rights for Ukrainian translations — although there have been cases of delaying the publication of books in Ukraine. The more Ukrainian publishers gain recognition abroad, the more trust they earn, and the better professional relationships are established. This makes cooperation easier and more fruitful,

explains Nataliia Miroshnyk, describing the challenges faced by Ukrainian publishers in the rights and translation market.

It was not until 2022 that the Verkhovna Rada passed a law banning the import of publishing products from Russia and Belarus. In 2023, the president signed the law into effect.

By maintaining a constant presence at events such as the Frankfurt Book Fair, Ukrainian publishers are gaining greater visibility in the global book market. This visibility helps them negotiate more effectively, both for the translation of foreign books into Ukrainian and for selling the rights to Ukrainian books abroad. According to Nataliia Miroshnyk, the growing separation between the Ukrainian and Russian book markets has improved the situation significantly.

“For our part, we can confirm this with a busy schedule of meetings. People want to cooperate with us. The Ukrainian market is developing rapidly and dynamically, filled with new titles, and rights are acquired even at the stage of an idea — before the book is published,” Miroshnyk explains, describing how Vivat negotiates with foreign publishers to secure translations into Ukrainian.

Interest in Ukrainian books is clearly on the rise. However, there are still challenges when it comes to translating works by Ukrainian authors into foreign languages.

“First of all, foreign publishing houses are primarily interested in works that they believe will sell well in their market. Ukraine has a lot to offer, but selling rights is a painstaking process. It’s essential to present the right book to the right foreign agent who might be interested in a specific topic. Long negotiations are often required before a publisher is ready to make an offer to buy the rights for their country. Additionally, there is the persistent issue of a shortage of professional translators who can translate from Ukrainian into their native language,” Miroshnyk says.

In 2024, The Telegraph's list of the top 50 books of the year featured three works by Ukrainian writers: The Ukraine by Artem Chapai, The Language of War by Oleksandr Mykhed, and Our Enemies Will Vanish by Yaroslav Trofymov. All three books explore themes related to war.

At the same time, foreign publishers are increasingly interested in translating both classic and contemporary Ukrainian literature. Works by literary icons such as Lesia Ukrainka and Valerian Pidmohylnyi are being revisited alongside the writings of modern Ukrainian authors. This demonstrates the growing influence of cultural diplomacy. For years, Russia leveraged books and authors as tools of propaganda, spreading its narratives globally. It dominated book markets across former Soviet states with Russian-language publications, suppressing the visibility of local voices.

Tchaikovsky and the Russian Heritage in Symphonic Music

While international cultural platforms and markets severed ties with Russia following its full-scale invasion of Ukraine and shifted their focus to Ukrainian culture and artists, the situation has unfolded differently in the realm of symphonic music.

In March 2024, Michael Gruber, agent of the Ukrainian conductor Oksana Lyniv, highlighted an unexpected trend: the performance of classical Russian composers increased in Europe, America, and Asia after February 2022.

“Conductors, regardless of their nationality, simply have to conduct and perform classical Russian composers such as Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, Shostakovich, Stravinsky, and others because these composers and their music have become part of the standard repertoire of every important opera house, orchestra, or concert hall in the Western hemisphere,” Gruber explained.

Indeed, Tchaikovsky’s music remains foundational to symphonic music as both an art form and a cultural commodity. His compositions, such as The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, have profoundly shaped cultural traditions, popularizing not only the story but also the nutcracker toy as a symbol of Christmas. Similarly, Swan Lake stands as one of the most iconic ballet productions of the 19th century, further cementing Tchaikovsky’s legacy in the global theatre scene.

The music of Russian composers has been a part of the world’s classical canon for so long that it cannot simply be removed or ignored. Oleksandra Zaitseva, director of the Youth Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine, emphasizes that composers such as Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff are integral to the tradition of classical music.

“Music, especially symphonic music, is a special kind of art. It is the branch with the fewest borders. Literature, for example, is often tied to specific events, characters, or even political situations. Symphonic music, on the other hand, conveys a more universal emotional message. The works of Russian composers have already become programmatic, and it’s impossible to avoid them in this realm. Russian composers were not confined to the empire or later to the USSR. Rachmaninoff, for instance, lived in the United States, and his music is beloved there. Many of these composers performed in Europe and the U.S., helping to open major concert halls. Their historical connection to symphonic music is undeniable—it’s impossible to remove them from the context of this tradition,” Zaitseva explains, offering insight into why Russian composers continue to hold a significant place in the world of symphonic music, both culturally and historically.

Despite this, concert organizers and tour planners now draw a distinction between the 19th century and the present, according to Zaitseva. “Contemporary Russian performers are not invited to concerts en masse. Of course, they avoid those who support Russia’s war against Ukraine and the policies of the current Russian government.”

Symphonic music and opera have not been immune to controversy surrounding Russian performers. For example, in March 2022, the Metropolitan Opera in New York City terminated its contract with Russian opera singer Anna Netrebko. Netrebko filed a lawsuit against the opera company and was awarded $200,000 in compensation. However, she was also required to pay $30,000 for her “very inappropriate” comments following Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

The Metropolitan Opera also replaced Anna Netrebko’s husband, Azerbaijani opera singer Yusif Eyvazov, in the production of Tosca. Peter Gelb, the General Manager of the Metropolitan Opera, explained that Eyvazov’s removal was due to the participation of Ukrainian performer Liudmyla Monastyrska.

Despite the controversy, Anna Netrebko has attempted to return to the international opera stage, this time through Germany. She performed at the International May Festival in Wiesbaden in 2023, though Ukrainian performers boycotted the event. Festival organizers dismissed the Ukrainian performers' position as “politically motivated” or “imposed by politics.”

In 2024, the German State Opera in Berlin announced that Anna Netrebko would perform Verdi’s Nabucco. Her husband, Yusif Eyvazov, was also included in the cast for another production. At a press conference unveiling the new season, the opera’s General Music Director, Christian Thielemann, expressed admiration for Netrebko, stating, “I admire Anna Netrebko.”

In February 2024, the Vienna Festival canceled a concert featuring Greek conductor Teodor Currentzis, who holds Russian citizenship. Ukrainian conductor Oksana Lyniv criticized Currentzis’s inclusion in the festival, calling it insensitive and dismissive of the suffering of Ukrainians.

On the other hand, Austrian-Russian conductor and Chief Conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Kirill Petrenko, has openly supported Ukraine and condemned the war, though he referred to it as “Putin's war.”

In an interview with UP.Zhyttia (Life), Ukrainian conductor Oksana Lyniv shared that she made a concerted effort to avoid collaborations with Russian artists. She even went so far as to find articles and public statements by Russian performers, sharing them with agents and organizers. In most cases, the organizers agreed to her requests.

However, it is impossible to entirely exclude the works of Russian composers from the classical repertoire. For instance, Ukrainian opera singer Oleksandr Tsymbaliuk sang the part of Russian Tsar Boris Godunov in Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov at the Munich Opera Festival. The reason for this is the undeniable classic status of Russian composers and their works.

“There is a certain distribution in the orchestra’s repertoire — 70% should be classical,” says Oleksandra Zaitseva. “This includes the staples: Mozart, Bach, Beethoven. Only 25%-30% of the repertoire can consist of more contemporary works. The less famous the orchestra, the smaller the percentage of its own repertoire. This leaves less room for performing works by Ukrainian composers.”

The Youth Symphony Orchestra, under Zaitseva's leadership, takes a principled stance against playing classical music by Russian composers. This policy will remain unchanged, as she affirms, “We will continue to hold on to this position.”

We are a non-governmental organization and position ourselves as the national youth symphony orchestra of Ukraine, the only one of its kind. With this in mind, we do not include works by Russian composers in our programs for several reasons. First, it is traumatic for our musicians, who feel the negative impact of such music in the current environment. Second, society might misinterpret such decisions, associating them with a lack of support for Ukraine. There is also the risk of raising uncomfortable questions abroad that could politicize our activities—for example, why we are performing Russian music now. However, it is important to emphasize that our project has always been linked to supporting Ukraine, and we have never had any such requirements for our repertoire. We are a non-profit educational and cultural project focused on developing Ukrainian musicians and promoting our culture. This is our mission and uniqueness,

says the director of the Youth Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine.

Despite the challenges, progress is being made. Oleksandra Zaitseva explains that foreign orchestras are now requesting music sheets from Ukrainian composers. The Liatoshynskyi Foundation has been engaged in distributing music scores by Ukrainian composers.

“These are signs of the successful integration of Ukrainian repertoire into the global music scene. This is a long-term process, but I believe Ukrainian music will eventually become an integral part of symphonic classical music,” Zaitseva says.

Ukrainian music is already part of global cultural heritage. For instance, the song Shchedryk, with music by Mykola Leontovych, is now a classic Christmas carol. Furthermore, The Way, a piece by contemporary Ukrainian composer Bohdana Froliak, was performed at the BBC Proms and has been included in the repertoires of several symphony orchestras. The Youth Symphony Orchestra also performs this piece.

Despite the decreased attention to Russia's war against Ukraine in foreign media, interest in Ukrainian culture remains strong. Oleksandra Zaitseva notes that Ukrainian works continue to receive positive feedback from audiences.

“We often hear, 'This is such a beautiful piece, I wish we had heard it before.' People ask us to share more about the works of Ukrainian composers that we perform. Audiences are starting to understand, become deeply interested in, and find something meaningful in Ukrainian music. This growing curiosity will ensure these works continue to be performed,” she explains.

While the symphonic music scene is discovering Ukrainian classics, such as Mykola Lysenko, and contemporary composers, it is impossible to entirely remove Russian composers from the repertoire. Their influence is deeply ingrained in symphonic music. During the Christmas season, for instance, Tchaikovsky's The Nutcracker and the Mouse King will be performed at many venues, but Leontovych's Shchedryk will be played alongside it, not instead of it.