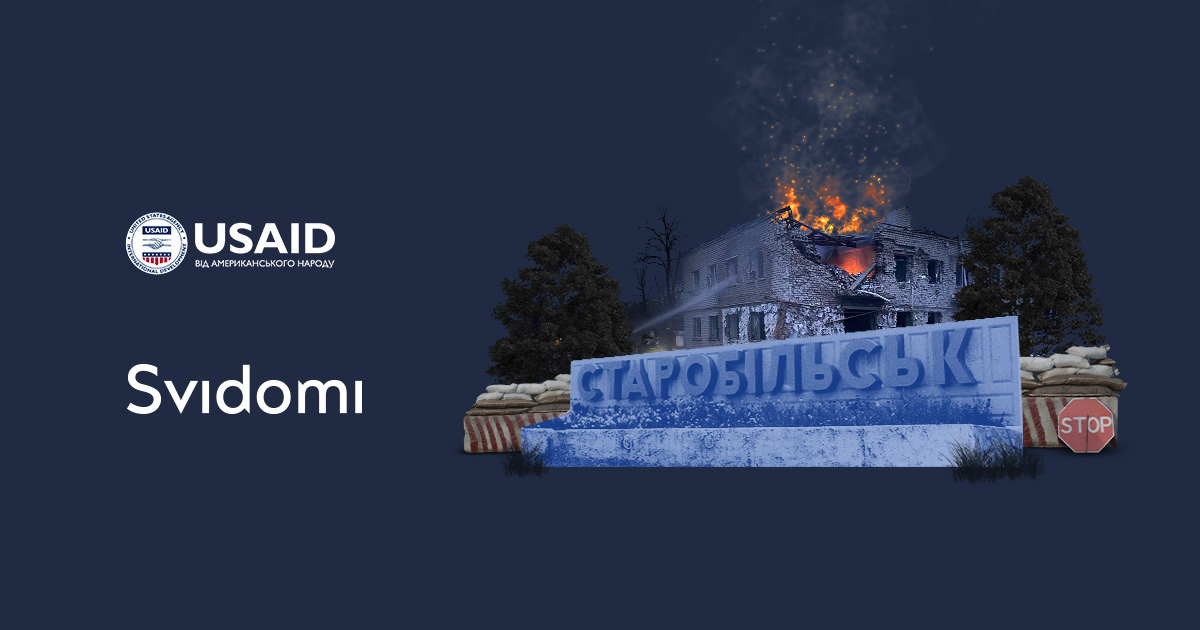

Voices of occupation. Starobilsk

The fighting near Starobilsk began in the early days of the full-scale invasion. When the Russians entered the city in early March, the locals resisted and went to the rallies with Ukrainian flags. Despite this, Starobilsk has been invaded and remains under the control of the Russian military.

"Svidomi" recorded the stories of the Starobilsk residents about the Ukrainian resistance, life in the city and the behaviour of the Russians.

Direct speech; names have been changed for security reasons.

The story of Anna

I was under occupation from the first day of the full-scale invasion until mid-summer. We were invaded in a short time, so it was impossible to leave immediately. Soon, telephone connections, the Internet and television disappeared. The collaborators from temporarily occupied “Luhansk People’s Republic”, who always looked intoxicated, erected roadblocks and hung up tricolour rags. Finally, schools announced they would issue Secondary School Certificates only of the "LPR" standard [Anna — this year's graduate — ed.].

At first, we still heard the sounds of hostilities. Then, however, it got much scarier when they began to subside, and the front line moved away. Then we were left alone with the occupation.

Some days aviation was almost constantly buzzing in the sky. One such day, reading Vera Ageeva's Behind the Scenes of the Empire, I realised that I felt the fear and wretchedness of the pilot flying nearby. I had more courage and dignity with a book in my hand than that creature in the air carrying bombs to Severodonetsk. Books have become a great counsel and shelter for me in the occupation.

Later, carriers appeared transporting people through Russia, so we left soon. Then we went to Poland to return to the territory controlled by Ukraine. I can’t describe the emotions when crossing the Polish-Ukrainian border. The moment I saw the Ukrainian flag was one of those I would tell my grandchildren about with tears in my eyes, recalling this war.

The story of Oleh

Even in the summer, I told my friends that an invasion could begin, and we needed to be ready for a possible occupation of the city. Then, around February 25, we started to hear shots, there was a missile strike in Starobilsk, and around March 2, the Russians arrived.

I worked as a project manager, so stressful situations are my element. I gathered my relatives, told them what to do, where to hide, and what things to take along, and took control over what was going on in our basement. Together with friends, we shared information about our locations, basement schemes, and places where Russians were staying and agreed on communication channels. When we learnt about the site of the Russian military, my friends and I sent tips to the Ukrainian special services and waited for the missile strike to go and pick up the weapons. I felt focused and organised. People around me also got together because of the desire to survive.

In our city, there were three or four mass pro-Ukrainian rallies in early March. Many of those who participated left having the opportunity. Mostly, no one remembered or paid any attention to activists. Although, there were cases when the military came to pro-Ukrainian people, took them to the basement, and then stories developed in different ways. Some disappeared, others allegedly committed suicide, and somebody else was taken for interrogation to the temporarily occupied Luhansk.

Residing in the temporarily occupied Starobilsk is an ongoing risk assessment. One always has to be careful about the milieu. People cannot openly express their position. You don't know who's who and who's for whom.

The story of Tetiana

I didn't believe in the breaking out of a full-scale invasion. On the contrary, I thought it was impossible, although, in a few weeks, the man warned that the Russians were already standing at the border.

When it all started, it was terrible. My brother called, and I could hear explosions in the background. The Russian army crossed the border at Milove [village on the border — ed.], and the first hostilities began. I didn't know what to grab. We live in the suburb of Starobilsk, so we went to the city to stay together with our parents. I left Starobilsk in June. At first, there was chaos in the city, people were driving around with trailers loaded with things, and there were huge queues at gas stations. Groceries were sold out in supermarkets, and there was nothing in the stores.

At the beginning of the occupation, people went to pro-Ukrainian rallies. Russians took down our [Ukrainian - ed.] flags and put up their own. People, together with the mayor, began to protest against it. Those men who removed Russian flags were detained. I don't know what happened to them next. People in the city have disappeared and still disappear. Some reported to the Russians where militaries’ relatives lived, and then they searched and robbed the houses. Some places were marked with red paint.

My brother had a bicycle. We were afraid to drive because we didn't know what to expect from them, so I rode my bike during the occupation. Many columns of Russian equipment drove through the city. I still had pets, so I often left the city by bicycle to feed them. I often went to the town and watched what was going on. In the first days, there were still our police officers, and then the Russians began to set up roadblocks, where they stopped and interrogated where I was going, demanding documents.

One day I was driving, and a woman called me to put out the fire because the Russians shelled a civilian house with an infantry fighting vehicle. I called the State Emergency Service, but no one came. The women from the house next door started to carry water to put out the fire. Men did not participate; they only watched because Russians were walking around. They must have been frightened. The Russians were circling with weapons. I asked them why they had done it. And they answered: "We were told here there was a warehouse of military ammunition". It was scary, but I felt frantic hatred.

The story of Danyil

In the early days, I was muddled in the head. I woke up to go about my business and automatically got hooked to the phone — the news was buzzing, there was panic in chats. I read the channels — hundreds of places suffered from shelling, Russian troops landed in Hostomel, and military vehicles crossed the border in many places. Preparations began - we covered the windows from possible glass fragments and slept in a room without windows. The city got crazy — queues for essentials, purchasing fuel, and tobacco products.

Some special operations officers came to our house - clean weapons with body kits, good uniforms and protection - to ask about a neighbour from another street. After that, they asked questions like "What battalion did he serve in? Where is he now? Where do his relatives/acquaintances live?" And a few more times on the street, the so-called patrol stopped, checked the documents, wondering what we were doing there. Once during the inspection, they asked questions about the acquaintances of the Ukrainian authorities, and most ridiculously, they asked: "Who is Bandera?".

At the beginning of the invasion, the city's residents tried to stop the columns of vehicles. But then it became clear that you would do nothing physically but only put yourself in immense danger. Moreover, during the protests, the Russians opened fire in the air. Subsequently, information activities began to disseminate coordinates of checkpoints, data on columns, photos of machinery, and information on the location of human resources. Unfortunately, many people changed the guise and gave away people. Some were detained, and others managed to escape. Those lucky remained in gaol, or "monkey house" [the slang name of a temporary detention isolator — ed.] for a couple of days; if not, they were taken to Luhansk "to the pit". No one knew what had happened to them.

Life in the occupation is like being a wick an inch from the fire: a light breeze — and you flare up. The danger can be everywhere. They can inspect your belongings and body for tattoos or check your phone. At these moments, you realise that you cannot ask, "on what grounds?" because you are nobody and nothing, you are not valued, you have no rights, and the patrols and the occupation authorities have no moral values.

We try to stay positive, despite what we have come through. Since our city was not particularly affected by the shelling, compared to other cities in Ukraine, I am 100% sure that it will be possible to bring life back there, but only if Russia does not pose any danger.

The story of Daria; quotes from the diary

I do not know where the shell hit, but the window in my room opened wide, and the shock wave dropped a huge crassula. I will be sweeping the earth and debris of the pot from under my desk for a long time. I stay awake almost all night, listening to new sounds: a torn windproof film hitting the window, a neighbour on the floor below with computer tanks, a sick child making a fuss, and the wind blowing. Every hour I check the news and ask everyone I know: "How are you?" Throughout this night and many nights to come, I wait incessantly, almost hopefully, for a rocket to hit my room so that it might be over before it even began.

Nothing changes for the morning — white bandages, the letter "Z" on the cars — just like the previous day. The night seemed quiet. In a few hours, we were recommended to hang the windows with something tedious: the "guests" decided to stay in the city and settled in educational institutions opposite my window. It is unlikely that they will throw fuel or peep into binoculars, but they can use torches to spotlight. I still tremble with my whole body when I'm in my room. The heavy mattress barely holds on to the nails near the window frame.

"Guests" still haven't left. Moreover, there is a video in which a soldier with a white cloth on his knee installs a tricolour on the district council building. The blue grace of God and the cloudless sky heroically shed blood — this is decoding the "Luhansk People’s Republic" flag. Subsequently, such flags will be on each critical building and later supplemented with Russian "Aquafresh". The trident on the city court will be half-broken, the flag of the city will be painted with a two-headed eagle, and the Soviet names of the streets will be restored. But Starobilsk residents do not know what lies ahead, so they assemble a second protest, the result of which is the return of the blue and yellow canvas to the main flagpole.

The forces of the Ukrainian administration, which remains in the city, settled the displaced persons in a spacious hall of one of the sports educational institutions. There are a little over a hundred of them. Older men with empty eyes. Adults who are preoccupied with maintaining more or less normal living conditions. Kids carelessly play with each other, huddled in a corner. Older people bring them toys and sweets to turn their attention away from the outside world. Milk and cereals are essential for infants. Remnants of the Ukrainian Ministry of Emergency Situations and volunteers prepare food, and one of the locals baked a bowl full of fragrant pies. Clothes are piled in a separate room. In the hall, mattresses and sunbeds are on the floor, and acrid fumes of rotten war rise to the ceiling. Volunteers ask the city's residents to take at least a few people to shower, and the rest try to get to one of the local baths.

Stocks of medicine and food are gradually running out. It will take many days before a safe way to Stanytsia [Stanytsia Luhanska — village near Luhansk - editor's note] or Luhansk, so that farmers could fill the shops and markets with goods. Prices will change the rate of rise and fall, and in the meantime, we will get used to living in the absence of any telephone connection and watching Russian news on TV and hearing their songs mixed with invitations to join the ranks of the people's police. The TV tower has been captured. Cultural and information pressure has been launched.

On May 8, they conducted surveys about life in the USSR or something of the kind — I did not participate personally, only saw close. In warehouses, monuments to Lenin were found and prepared for installation. Invitations to the Victory Day demonstration were hung on all the buildings. Do they think we've been forbidden to celebrate it for eight years? Why did everyone stick to this term at all? My region was part of Ukraine from the very beginning of its independent formation. Someone's not in the right place with the story. On May 9, the rally did not work — there was still a procession with flags and songs. Some people recognise familiar faces in the photos with bitter pain. In the video, residents say they are finally free to celebrate Victory Day. That is, in recent school years, I did not shout in the square winning songs, did not give veterans flowers, or did not cover them with umbrellas from the rain during the parade. So, yes, it was a dream. I write this diary on Republic Day. All night and day, they are driving the machinery again — Staryk [local abbreviation of the city name — ed.] turned into its landfill, a good transport hub, handled gently and carefully. How unspeakably unfortunate that everyone is already accustomed to such sounds.

Day 100 begins at 5:30 with a powerful explosion — flashbacks from the second day. Someone says the plane broke the sound barrier. Some have managed to photograph a white trail in the sky, which leads to the theory of the work of air defence. Some convince me: it fell there/went off over my house/flew further. The truth is that everyone could hear it so well that even the car alarm went off.

During the hundred days, we ran to the basement for literally several days until we got used to distinguishing the strikes at the city, in fact, there were no strikes after the second day, from the strikes at the surrounding areas. We warmed ourselves with dry alcohol and joked while the elders muttered prayers. We learned to hear dozens of sounds and sleep soundly at night in our pyjamas, ignoring the wind that carried the sounds of close battles. The white armbands, the three famous letters on the vehicles that rush back and forth. Even planes that are so bold that they are already hovering over the cities. Destroyed blocks of houses. Rubles, lack of communication and regular Internet. For a hundred days, we have got used to the new reality where we are already skillfully surviving.

The story of Sergii

I have been a combatant since 2015. I woke up an hour after the fighting began. I heard a loud explosion at six in the morning — it was the first missile strike. Honestly, I didn't know what to do at first. I packed an emergency case at the ready. I put on my uniform, took my backpack and left at random. We had already started to gather, to develop the defence of Starobilsk — we joined the military and the territorial defence. Our military broke one Russian convoy with two tanks and stopped the second.

When I was thrown to the edge position, where there was a bridge over the river, my colleagues and I got into a ring. I could not get out. I decided that there was only one thing left for us here: either to break through the Russians, but it is not known whether we would come out alive or to run home to change clothes and hide so that we would not be seen. We chose the second option. I moved over the river to return home and threw all the weapons into it. It was dangerous to move around the city with weapons. I happened to come out in one place, dressed in uniform, and there were already jeeps of the "DPR". I managed to retreat a few steps back and fell between the trees, under the fence, so they could not see me. Until March 8, I was moving around the city, looking for shelter, realizing that if I were caught, I would not survive. Nevertheless, I was not going to give up. Later I managed to leave Starobilsk, and I started military service in April.

Russian soldiers started looting in Starobilsk. Many members of the Aidar battalion lived in our town, so, first of all, Russians came to them: they broke windows and took everything they could. This fate did not spare me either. On April 13, they broke into my house: broke the door, and smashed everything. They took away dishes, fishing equipment, electronics, and a kettle. The most exciting thing they took was a box for dirty laundry. It says a lot about them.

The city can be returned to its pre-war state, but it will be difficult. Everyone has always believed that Luhansk and Donetsk regions are pro-Russian. I disagree with this. Most people are pro-Ukrainian and are waiting for our people to come.