The Ukrainian identity in the creative works of artists from the south of Ukraine

Russia has spread many myths about the south of Ukraine. The main one is that before the arrival of the Russian Empire, there was a wasteland on the Black Sea coast, and, most importantly, there was no Ukraine. Therefore, artists from the region cannot be considered Ukrainian, because they had no Ukrainian identity and did not manifest it in any way.

This is not true, of course. Artists from Kherson, Mykolaiv, Odesa and other cities of southern Ukraine considered themselves Ukrainian, expressed this in their work and suffered for their identity at the hands of the Russian imperial and Soviet authorities.

This article tells about artists from the south of Ukraine and how they embodied Ukrainian identity in their works.

Yukhym Mykhailiv

The Oleshky artist and art historian Yukhym Mykhailiv is considered a representative of Ukrainian Art Nouveau. He studied in Kherson and then at the Moscow School of Painting.

After graduating in 1910, he was drafted into the Russian army. He took part in World War I, where he was wounded. In 1917, after the collapse of the Russian Empire, he moved with his family to Kyiv, where he worked as an art teacher at a gymnasium.

In the last years of the empire, Mykhailiv painted three paintings of the sonata 'Ukraine' — 'An Old Graveyard', 'Rest Disturbed' and 'Wandering Spirit'. All three sonatas are united by the spirit of a Cossack moving from the cemetery to the hill and wandering along the riverbank on a weightless gust of wind. In the second painting, 'Rest Disturbed', the artist directly depicts the spirit of a Cossack on horseback travelling across Ukraine. This was Mykhailiv's way of expressing his sense of belonging and identity in imperial times.

After the Bolsheviks came to power in the 1920s, Mykhailiv continued to work as an art teacher in Myrhorod and Kyiv and wrote and published research papers on art history, especially Ukrainian art. He was particularly interested in ceramic art but also wrote about other artists of his time, such as Heorhii Narbut, a Ukrainian illustrator who designed banknotes for the Ukrainian People's Republic, and Oleksandr Murashko, a Ukrainian impressionist who was one of the founders of the Ukrainian Academy of Fine Arts in 1917.

During the Ukrainianisation policy, Yukhym Mykhailiv became one of the leading Ukrainian artists. His paintings depicted the historical periods of Ukraine's past. His painting 'The Stone Babas' depicted the Cuman idols that remained in the east and south of Ukraine. 'The Golden Gate' depicts the ruins of one of the entrances to Kyiv from the Kyivan Rus, and 'Lost Glory' shows a Hetman's mace in a field. The title of the painting may indicate the artist's attitude to the period he depicts — he regrets the decline of the Hetmanate (historical term for the Ukrainian Cossack state of the 17th and 18th centuries — ed.) and the disappearance of the Cossacks, caused, among other things, by the actions of the Russian Empire.

Vladyslava Diachenko, deputy director of research at the Kherson Art Museum and an art historian, says that Yukhym Mykhailiv actively expressed his identity in his art and everyday life.

"He was a conscious Ukrainian. He wore an embroidered shirt (vyshyvanka — red.) and spoke Ukrainian. Unfortunately, most of his work has been lost. Some of it was taken to America by his relatives because he was also repressed there in the 1930s. The Soviet authorities killed him because of his work and his position. Very little of his work survived, and the Kherson Art Museum does not have any of his paintings," she says.

In the 1920s, Mykhailiv developed the avant-garde in Ukrainian painting. His paintings are full of symbols, bizarre shapes and someone from the other side. In the painting 'Road of No Return', he paints the road to death, flooded with light. And in the painting 'Chained Art' — a tree in a chain. Perhaps Mykhailiv sensed what would happen next, for in 1925, when this painting was published, Ukrainianisation was at its height. In five years, everything changed.

Yukhym Mykhailiv's art changed too. He began to paint naturalistic works of neutral content, such as still life and landscapes, and even paintings glorifying industrialisation, such as 'Building the Brig' (1933).

In 1934, Yukhym Mykhailiv was arrested unjustly on charges of preparing an armed rebellion and exiled to the Arkhangelsk region. There, he got a job as a decorator for a local club. He dreamed of returning to Ukraine. But the harsh conditions of imprisonment and the Siberian climate made him seriously ill.

Yukhym Mykhailiv died in exile in 1935. Shortly before his death, in a letter to his family, he wrote a poem that included the following lines

"...I was exiled — I don't know why.

For Ukraine, that I am her son".

Volodymyr Chupryna

"This man has been passionate about Ukrainian art since Soviet times. He spoke Ukrainian and always performed in Ukrainian at a time when no one in society was even talking about language. It was a conscious position," says Vladyslava Diachenko about the artist Volodymyr Chupryna.

Volodymyr Chupryna is 83 years old. He comes from the Kherson region, where he became an artist, art critic and teacher. Volodymyr Chupryna is one of those who still remembers World War II, as he was born in 1940. He studied in Kyiv and then returned to Kherson. The nature of the Ukrainian steppes became a leitmotif in Chupryna's artistic work.

In 1975, Volodymyr Chupryna became the head of the Kherson Regional Department of Culture. During his tenure, libraries and museums of local history and art were built in Kherson. He also researched and published works on the ethnography of the Kherson region and the works of artists such as Heorhii Kurnakov, a Ukrainian artist from Mariupol, Anatolii Platonov, a painter from Kherson, and others.

In the 1980s, Chupryna began to exhibit his paintings at various exhibitions in the USSR and abroad. He painted and still paints in watercolours, mainly depicting the nature and architecture of the Kherson region.

Volodymyr Chupryna's 1988 painting 'Sunken Antique Courtyard' depicts sunken Greek columns. There were Greek colonies in southern Ukraine, so Greek culture is natural for this region. But the most important thing is the time in which he depicts it. In the 1980s, the USSR underwent 'perestroika' — economic and political changes to maintain the communist regime. However, the cultural sphere was still dominated by socialist realism and Russian culture. So Chupryna's appeal to ancient history and its combination with Ukrainian history seemed like a creative challenge to the system.

"Chupryna painted monuments of Ukrainian architecture, and he loved to travel to different parts of Ukraine — to Chernihiv and Crimea. He always captured architectural monuments and antiquities in general. This is a Ukrainian theme, which was always present in his work," says the art historian about the meaning Chupryna gave to his landscapes.

In 1989, Volodymyr Chupryna presented his new painting 'Dachka'. It shows tiny houses hidden in the background of a monumental mountain road, mountain relief and nature.

He often painted still lifes, especially with flowers. Sunflowers appear at least twice in his works. They can be used to trace Volodymyr Chupryna's development as an artist. His early works are full of dark, almost monochrome colours. Since the '90s, he began experimenting with colours, light and watercolours, painting brightly as if trying to convey the sun-drenched landscapes of the South. This change was noticeable after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The independence that Ukraine regained at that time seemed to influence the artist's work.

"Sunflowers are Volodymyr Chupryna's favourite subject in his still life paintings," confirms Vladyslava Diachenko.

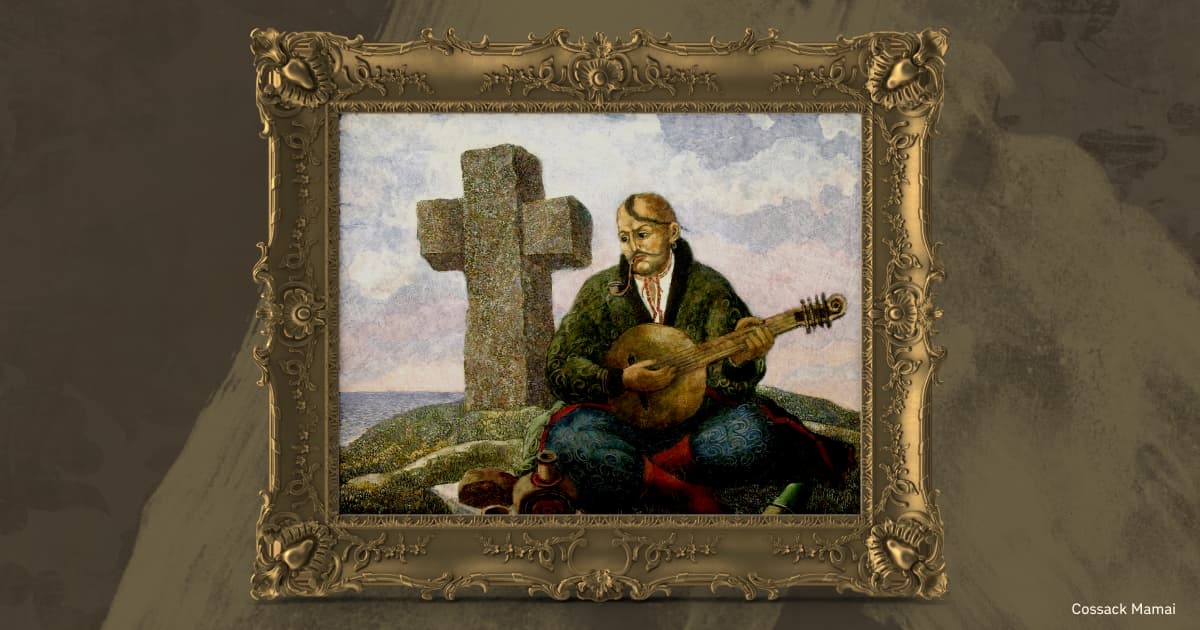

Volodymyr Chupryna has returned to historical subjects more than once in his career. He paints the Cossack Mamai, a bandura player who conveys a sense of freedom and the impulse to create. It is a symbol of the fullness of life. But while Cossack Mamai is depicted next to a horse and an oak tree in many paintings, Chupryna shows him on a grave, next to a Cossack cross, with a green field and water behind him. This is a typical landscape of southern Ukraine, with many old, even ancient, Cossack cemeteries. There are cemeteries in Mykolaiv, Odesa and Kherson. The green field represents the steppe. In this way, Chupryna fits Cossack Mamai into the nature of southern Ukraine and shows that it is a harmonious combination, that Cossack Mamai belongs to the steppe and the south of Ukraine.

In an interview in 2016, Volodymyr Chupryna said he was invited to work at the Ministry of Culture in Kyiv. But he refused.

"I worked there for two days, and I missed the Kherson region so much... I can't live without the Kherson region".

The village of Stanislav in the Kherson region, where Chupryna's studio is located on the banks of the Dnieper-Buh estuary, was under occupation until its liberation in November 2022. The Russians stole 57 paintings by Volodymyr Chupryna from the Kherson Art Museum and took them to Crimea. Their exact fate is unknown. Only in 2023 was it possible to identify 'Dachky' and 'Sunken Antique Courtyard' in a photograph taken at the Central Museum of Tavrida in the temporarily occupied Crimea.

Oleksii Shovkunenko

Although originally from the Kherson region, Oleksii Shovkunenko lived and worked for a long time in Odesa and Kyiv. He was one of the driving forces behind the Ukrainianisation of Odesa in the 1920s, teaching art history at the Art College and later at the Art Institute. He created a whole collection of portraits of Ukrainian cultural figures, including poets Pavlo Tychyna and Maksym Rylskyi, actress Nataliia Uzhvii, writer Yurii Yanovskyi, composer Mykola Lysenko and many others. Shovkunenko was a long-time friend of Tychyna.

However, the repressions of the 1930s affected the artist's work. Shovkunenko painted portraits of workers at the Odesa Shipyard, collective farmers and the working class. He also painted 'The Construction of the DniproHES Dam', which shows one of the stages in constructing a hydroelectric power station. Like many artists of the time, Shovkunenko moved towards socialist realism, more due to the demands of the Soviet authorities and censorship than his wishes.

Art historian Vladyslava Diachenko says that despite the total subjugation of art to the demands of the Soviet government, Shovkunenko tried to preserve his style in his paintings.

"It was dangerous to express his position openly because it was immediately Article 58 — Ukrainian nationalism. However, the artist expresses his position through art. Shovkunenko has done enough to be considered a Ukrainian artist. Many of his works clearly show his love for Ukraine. In Stalin's time, in the 1930s, he painted a wonderful piece called 'Girls with a Goat' in Ukrainian folk costume. He painted his wife in Ukrainian folk costume. He painted Ukrainian landscapes in the Kyiv region, where he worked. It's obvious. You just have to look at it," she says of how artists communicated their belonging during the repressions.

As a representative of early modernism, Shovkunenko began to paint in the style of impressionism and carried it through to his later work in socialist realism. Broad brushstrokes and lots of light and bright colours are all characteristic of Impressionist works. In his painting 'On the Dnipro. In the meadows. Kherson' (1914), Shovkunenko used broad strokes to depict the river bank, green plains and a light-filled background. He painted this picture under the Empire when socialist realism did not exist.

But if you compare the 1914 painting with his 1960 work 'By the River', you immediately see the same broad brushstrokes, the bright red colour of the boats and clothes, and the smeared faces of the two boys on the riverbank. This is a style of reproducing the impression of a scene that the artist noticed on the river bank, most likely in the Kyiv region, which is not typical for socialist realism. After all, Shovkunenko taught at the Kyiv Art Institute from 1936 to 1965.

"Oleksii Shovkunenko never had a single personal exhibition in his life," says Vladyslava Diachenko. "In the Soviet Union, you could only exhibit Lenin and Stalin. He painted his friends, Ukrainian figures and Ukrainian landscapes, so he had nothing to exhibit."

According to the art historian, Shovkunenko avoided exhibitions and meetings of the Union of Artists because they pressured artists and demanded loyalty to the authorities and commitment to socialist realism.

"He was accused of not being academic enough, of not being close enough to official art. His painting style is similar to that of the Impressionists, and it is very free. He was a free man. He had this view of the world. How he managed to keep his teaching position at the Kyiv Institute is unknown. Perhaps his friend Pavlo Tychyna helped him. At the time, he was a party member and held a position in the Commissariat for Education in Soviet Ukraine," says Vladyslava Diachenko of Shovkunenko's relationship with the Soviet authorities.

Although Shovkunenko lived most of his life in the Kyiv region, he never forgot his native city of Kherson. In 1921, he painted 'Green Bazaar', a landscape with a port bazaar in Kherson. In 1950, he recreated this painting based on his old sketches. According to Vladyslava Diachenko, this was done out of nostalgia for those years. In 1921, there was no USSR — the union was created in 1924. But there was no more Russian Empire. Although the Ukrainian People's Republic had lost control of its territory, Soviet Ukraine was already in place, and there were still hopes of some form of Ukrainian independence. These hopes were eventually crushed by Stalin's terror and the Holodomor (a famine imposed by the Soviet authorities in 1932-1933 — ed).

Oleksii Shovkunenko died in Kyiv and was buried at the Baikove Cemetery. The Kherson Art Museum was named after him. The museum collection included 154 paintings by Shovkunenko. During the retreat from Kherson in November 2022, Russian troops looted the museum and took away more than ten thousand works, including Shovkunenko's paintings.

Vladyslava Diachenko, deputy director of the Kherson Art Museum, describes the process of identifying the stolen works and whether it is possible to force Russia to return them.

"We are working on identifying the works. We are looking for photos and videos on the Internet from some news reports from Crimea, where Tavrida museum workers speak and testify that they received our collection. It's more difficult from there because they can leave something in Crimea or take something away. The Russians, of course, tell us how they 'valiantly' saved these paintings. Of course, we cannot answer questions about the case investigation and the possibility of returning our collection. We are waiting for at least some kind of diplomatic relations to be established so that we can negotiate. So far, we have no such leverage over Russia, and we have no way of forcing them to return our paintings,"

she says.