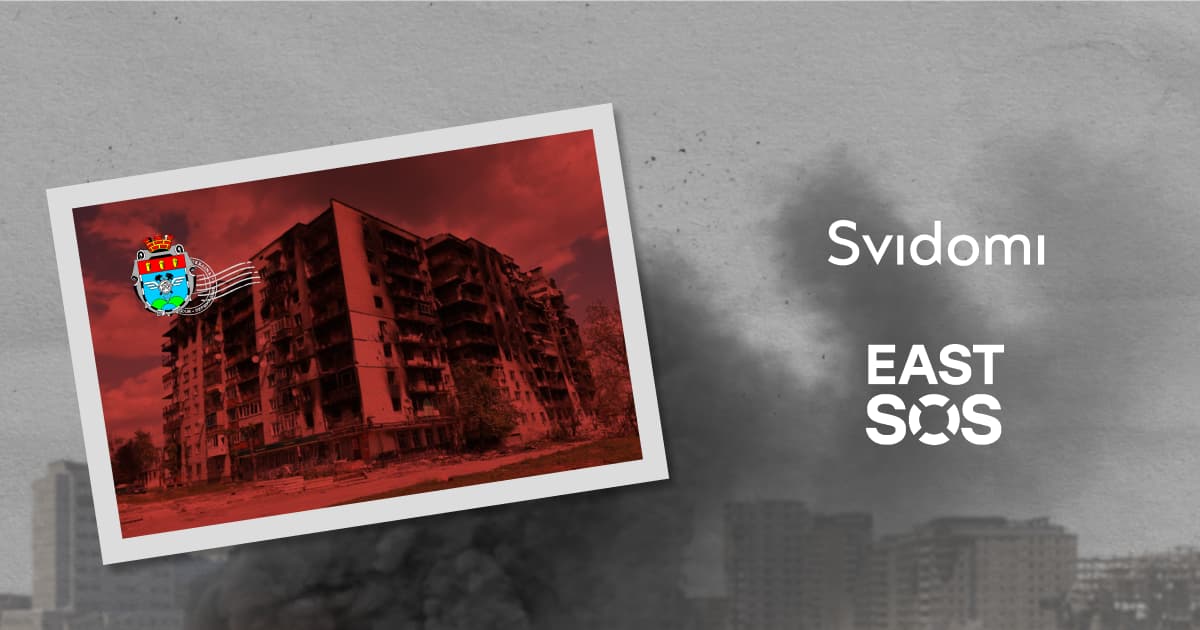

The story of a man whose family was saved twice by the decision to evacuate: "The house where we rented an apartment was destroyed. Then we realised it was the second time we had managed to escape"

Mariia Biliakova

Since 2014, Charity Foundation East-SOS has been collecting information about war crimes committed by representatives of the Russian Federation to ensure justice and the right to truth. Since February 24, 2022, documenters have recorded more than 600 stories and about 700 cases of alleged war crimes. Mariia Biliakova, the author of the article, recorded the story of Serhii Sharpan.

I was born and grew up in Popasna. After the army, I got a job in the mechanical workshop of a glass factory, where I worked as a turner until 2005 when I was laid off. Later, I was offered a job at the railway, where I had to lay and repair tracks. The station was an important transport hub, from here, you could go to Luhansk, Debaltseve, Bakhmut, Horlivka or Donetsk.

On February 24, 2022, my wife was about to leave for work, she is a teacher at a lyceum. In the morning, one of her parents called her and said: "Have you heard? The war has broken out". She replied that it could not be true and continued to get ready. I used to leave early because I had a shift at 7 a.m., and she had to be there at 8 a.m. I came to work and people were in a fuss. We were given our work record books and told not to come to work. I went home, and my wife stayed at home too. We learned that enemy tanks had entered Kharkiv and Kyiv.

We lived on the outskirts, by the road towards Bakhmut. From the first day, we saw columns of cars leaving the town. We decided to stay. We thought it would be like 2014.

On February 26-27, the Russians shelled the outskirts of Popasna for the first time. Then we moved our belongings to the cellar. I installed a light and a heater there. I remember that in 2014-2015 we did not spend a single day in the cellar, even though our house was shelled in the summer of 2015.

In the first days of March, the Russians attacked our yard with Grad rockets. It was dark, so my neighbours and I walked around with torches and went to the garages. We found some rocket wreckage, it was burning. Later the lights started to flicker — the power went out. I switched off the circuit breakers in the entrance hall to prevent a fire.

A shell exploded near another entrance, and the explosion shattered the windows. We helped the victims find plastic sheets or plywood to cover them. I called my brother, who lived nearby. Their windows were also blown out in two rooms. That evening we stayed in the basement for another hour and a half. It was very cold and there was snow on the street. The door was not locked because it was the only way out. We had a crowbar and an axe so we could get out if it collapsed. Then we went home and spent the night there.

We all cooked together in the street. It was good that there were wood-fired grills and firewood in the garages. We started by preparing things that would spoil without a fridge. We had a cauldron for three families, and the girls cooked ready meals in their flats. People from other blocks also got together and cooked for several families.

Sometimes we would hear explosions somewhere in the fields, and we would hide. We lived in our flat for a few more days. Some people packed up and left. Some fled to other areas, mostly to the private sector, where people had stoves.

A friend of mine lived in the building next door, but he often visited his mother in another residential area. He heated her house and sometimes spent the night there. On March 4 or 5, I went to his house. His wife opened the door for me, and heavy shelling began. It seemed as if the house was going to collapse. Everything in the house shook: dishes, furniture, walls. A dozen or more rockets were flying nearby. We hid according to the rule of "two walls" [it is safe to hide in a place behind the second retaining wall from the facade - ed]. .... Then the Russians must have reloaded their weapons, and the shells started flying again. The direction from which Popasna was shelled has not changed since 2014 - it was either Pervomaisk or Irmino.

I ran home, my wife was shaking with fear. I said we would leave immediately. It took us 15 minutes to pack. Since 2014, we had bags of things and documents that we hadn't unpacked. It was only after February 24, that we added some things. I went outside, checked the garage, drove the car out and put the bags in. We got in the car and drove away.

When we arrived in Bakhmut, life seemed so peaceful: people were moving around the town, cars were driving, and petrol stations, shops, and supermarkets were open. It was as if we were on another planet, just 30 kilometres away.

We rented a house for ten days, and then we hoped to return home. The Russians shelled Popasna more and more. People were constantly hiding in cellars, including my brother and his wife. It was almost impossible to get out and about.

Shops and pharmacies were no longer open in Popasna. Volunteers bought petrol at inflated prices, filled up their cars, took bread, food, medicine, candles and fuel, and then took it all to the town. They evacuated people on the way back. We did this several times under fire. The authorities took people away in school buses.

Another friend of mine often brought fuel or food and took people out of the cellar, but he did not take anything from his flat. A staircase in their entrance had fallen down, and the iron door to their flat was jammed. There were bars on the windows, and there was no time to open them because the shelling could start at any moment.

I followed him on one of those trips to pick up some of my friends, summer tyres and some things. I saw that our flat on the ground floor had been hit, the ceiling had been punctured. As I found out later, a rocket hit the basement where people were hiding, and they got blast injuries... It happened on the evening of March 30.

A powerful blast blew out many doors, damaging the neighbours’ flats. I was afraid the explosion had damaged and locked our front door, but it opened. The windows and doors in the two rooms facing the courtyard survived. In the bedroom, the window was blown out; it was in the folded wardrobe.

I was at home when the Grad shelling started, I heard the sound of rockets being fired 10 to 20 times. I took my things to the car, went back to get some bags, and suddenly Grad rockets started falling. I didn't risk running the third time because if they hit my car or a wheel, I wouldn't be able to leave.

My brother and his wife stayed in Popasna until April. We offered them to move to Bakhmut. Although it was a one-room flat, it had a big sofa. They refused. When their windows were shattered, I said: "What is more precious to you: your property or your life?" but they left only after the ceiling collapsed in the neighbouring basement, burying their friends. Then they jumped out of the basement and didn't even run in to get their belongings. On the way, they punctured a tyre somewhere and managed to get to us on a disc.

Later, my wife and I moved from Bakhmut to Zaporizhzhia because the Russian army started bombing the city. We decided not to tempt fate again. Later we found out that the house where we had rented an apartment had been destroyed. Then we realised it was the second time we had managed to escape.