The Obliteration of Cultural Identity: How Russians Destroy Culture Under Occupation

The removal of museum collections, the flooding of the museum, and the so-called 'reconstruction' of cultural monuments are all Russian methods of destroying Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar identities. The Russians are trying to erase the culture and heritage of the temporarily occupied territories to promote their propaganda narratives.

Read more about how the Russians are destroying cultural monuments in Crimea (Qırım), plundering the museum in Kherson and flooding the museum in Oleshky, Kherson region.

Cultural monuments of Crimea

According to the Crimean Institute for Strategic Studies, there are 5,342 monuments of local and national significance in the temporarily occupied Crimea. In particular, the number of cultural objects stored in museum institutions in 2014 was about two million. However, the actual number may be even higher.

During the temporary occupation of the peninsula since 2014, Russia has registered more than 150,000 cultural property items in its state registers, said Elmira Ablyalimova-Chiygoz, project manager of the Crimean Institute for Strategic Studies.

"Russia is destroying, stealing and appropriating Ukraine's historical and cultural heritage. This is a form of humanitarian aggression aimed at erasing the cultural identity of the territory and the ethnic identity of the peoples living in these areas. Because it is a cultural heritage that connects people to the territory and to the history of that territory, it is the cultural aspect of heritage that creates a sense of belonging when we say, 'This is my land, my country, my history'," Elmira Ablyalimova-Chiygoz explains in a commentary for Svidomi.

Russia is using museum institutions as a tool to implement its ideology. The Crimean Institute for Strategic Studies analysed this using the example of the Central Museum of Tavrida, which has been the methodological centre of the Crimean Museum network since 1921 and now claims to be the central museum institution on the peninsula.

"It is supposed to comprehensively reconstruct the history of the peninsula in all its diversity, but since 2014, the museum has been an active participant and tool for propagating the Russian myth of 'Russian Crimea'," says Elmira Ablyalimova-Chiygoz.

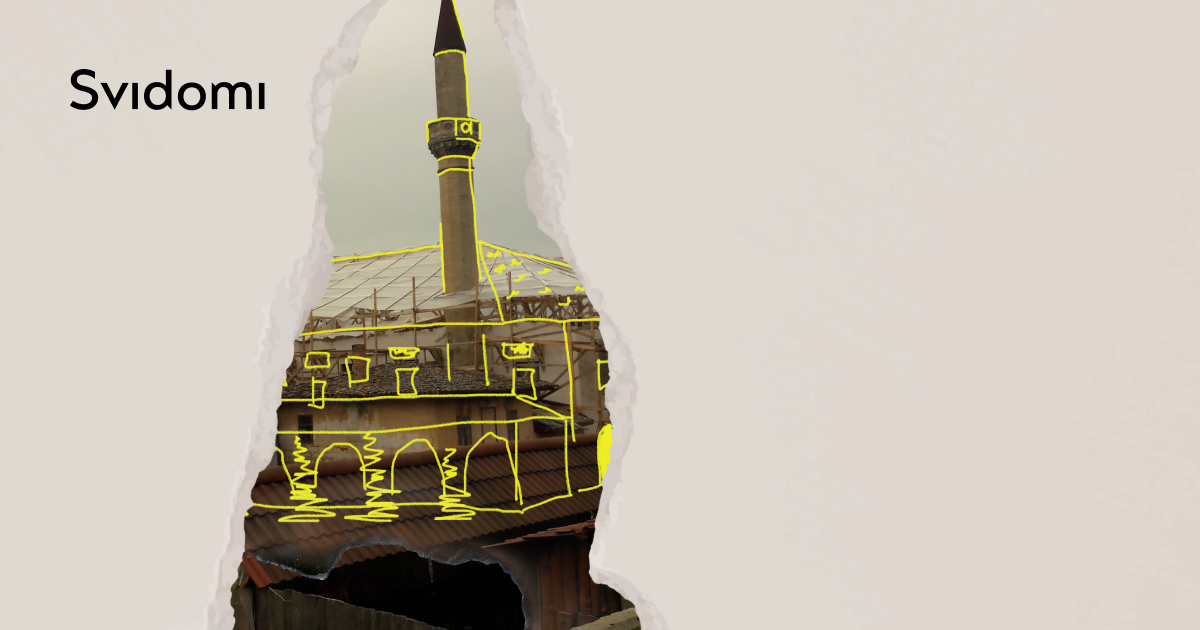

The most prominent example of the decontextualisation of cultural heritage is the story of the Bakhchysarai Khan's Palace, which is gradually losing its authenticity as a result of the actions of the occupying authorities.

The Russians are carrying out illegal construction/repair work on the monument, which results in changes to the monument and deterioration of its aesthetic, historical, scientific and artistic value. At the planning stage, instead of restoring individual elements of the mosque's historic roof, the Russians decided to completely demolish the roof and apply construction methods and standards to the heritage site as if it were a modern building.

Cultural heritage sites near the mosque were also damaged. Cracks were found in some tombstones in the Khan's cemetery, probably due to mechanical insecurity.

"The situation with the Khan's Palace is extremely tragic. We are losing the historical value of the monument, which is proof of the existence of Crimean Tatars on the territory of Crimea and the existence of our statehood. This is the only material testimony to the fact that the indigenous people belong to this territory," said Ablyalimova-Chiygoz.

After the full-scale invasion, Russia's actions against the cultural heritage of the peninsula only reinforced the already established pattern and extended it to the newly occupied territories.

"The scale of destroyed cultural sites, completely destroyed museums, religious sites, etc., is so great that it can be compared to a humanitarian catastrophe, the consequences of which we will feel more and more acutely every year,"

says a representative of the Crimean Institute for Strategic Studies.

The Russians have all but destroyed the ancient suburb of Taurian Chersonesus, an ancient Byzantine city-state founded in the fifth century BC and listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Russians carried out "excavations" there: first, they brought in excavators, and the work was carried out so that some of the information about the past of Chersonesus was lost. This is the destruction of the original appearance of Chersonesus, its identity and the physical evidence of the existence of the ancient city.

"It is no exaggeration to say that the main research centre of the ancient city, the Chersonesus National Reserve, has practically lost its scientific archaeological school. Today, Chersonesus is the cornerstone of Russian propaganda about 'Crimea is Russian', so many things are being done according to the 'wishes' of both the Russian Orthodox Church and Putin himself. And all this is a disaster for the monument," says Elmira Ablyalimova-Chiigoz.

Experts from the Crimean Institute for Strategic Studies are already collecting materials on the issue and planning to develop certain existing international practices that could be useful to us.

"If we want to preserve ourselves as a people, we have to preserve our cultural heritage, and we have to research and study our history, we have to speak our language, and so on. This makes us Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians," emphasises Elmira Ablyalimova-Chyygoz, the Crimean Institute for Strategic Studies project manager.

Kherson Regional Art Museum

At the beginning of March 2022, the Russians occupied Kherson. At the same time, the Russian military came to the Shovkunenko Kherson Regional Art Museum to check the suitability of the building for use as a military facility.

"For the second time, in May 2022, several armed and masked men came to the museum. They asked for information about the staff, the director and the collection. They ended by threatening to come back next time and, if they felt it necessary, to take the rest of the collection to Crimea or perhaps even further into Russia," recalls Hanna Skrypka, chief curator of the funds of the Kherson Regional Art Museum named after O.O. Shovkunenko, in a comment to Svidomi.

According to Hanna, the Russians seized the museum on July 19, 2022. They appointed a resident of Kherson as its director, who had previously worked as a teacher at the College of Culture.

Earlier, the occupation authorities had called the museum's director, Alina Dotsenko, and offered to hold an exhibition until May 9. When she refused, she received threats and an invitation to the commander's office, where she would be "taught to respect the new government".

Overnight, Dotsenko packed her bags and headed for Ukrainian-controlled territory. She sewed valuable documents to her belt, and three days later, she was in Kyiv.

"After the seizure of the museum, the Russians twice organised 'travelling' exhibitions of works to introduce them to the local population and create an image of peaceful life in the city,"

says Skrypka.

It was impossible to move the collection to a safer region of Ukraine. However, the museum workers said they managed to "fool the Russian military" for five months because the museum was closed for repairs before the full-scale war.

"Everyone believed that the collection would be removed in two stages — the first before the [full-scale] war in the autumn of 2021, and the second in May 2022, when director Alina Dotsenko was forced to leave for Ukrainian-controlled territory," says Skrypka.

"The Russians wanted to prepare another exhibition but didn't have time. At the end of October, they began to pack up and evacuate the artworks, claiming that they wanted to 'save the valuables' from the Ukrainian army.

Before leaving Kherson in the autumn of 2022, the Russian army illegally removed the Shovkunenko Kherson Regional Art Museum collection under the slogan "We are saving the exhibits".

"Over ten thousand museum items were stolen from October 31 to November 4, 2022. During those days, several tent trucks illegally transported the museum's valuables to the Tavrida Museum in Simferopol in Russian-occupied Crimea," says the museum's curator.

Among the stolen works are 'On the Riverbank. Sunset' by Ivan Pokhitonov, 'It's Autumn Time' by Heorhii Kurnakov, 'Gladioli' by Leonid Chychkan and works by Oleksii Shovkunenko.

On November 11, 2022, the Ukrainian Armed Forces liberated Kherson. The museum then moved the remains of its collection to a safe place.

"The museum staff (after the liberation of the city — ed.) made lists of the looted and surviving remnants of the museum collection. Museum staff are identifying the lost works. The list already contains more than 100 works. We have experience in cooperation with foreign human rights organisations. We are also working hard to prepare forms for each stolen object to further appeal for help from Interpol," says Anna Skrypka.

House museum of the artist Polina Raiko

In June 2023, in the temporarily occupied town of Oleshky in the Kherson region, the house museum of the Ukrainian artist Polina Raiko was flooded due to the explosion at the Kakhovka hydroelectric power station. The museum staff managed to evacuate.

Polina Raiko is a self-taught Ukrainian artist who is a representative of outsider art. She started painting at the age of 69 and, in a few years, painted her own house, summer kitchen, gates, fences and garage doors. She used the simplest and cheapest paints.

"When Polina Raiko was left alone (she had no contact with her family — ed.) during the renovation of her house, she began to paint it. First, she painted a bird that her neighbour liked. After that, she began to decorate the house even more," Semen Khramtsov, a representative of the Polina Raiko Kherson Regional Charitable Foundation and the artist, recalls in a comment to Svidomi.

After the artist died in 2004, a couple of art admirers from Canada bought the house, and thanks to them, the house with the paintings was preserved.

"Later, the couple left Ukraine. The old ladies of the village started to look after the house. They paid for the gas, planted flowers in the garden and took care of the house at their own expense," says the artist.

In 2004, artist Viacheslav Mashnytskyi established the Polina Raiko Kherson Regional Charitable Foundation to preserve and promote her name. The foundation was mainly involved in the Kherson Museum of Contemporary Art. Renovation of the house-museum began after 2015 when the building was in poor condition.

In October 2022, Mashnytskyi went missing. His whereabouts are still unknown.

Before Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, this house museum was a venue for festivals, residencies and film shoots. In Ukraine, Polina Raiko's house is protected by the law on protecting cultural heritage.

"After the occupation of Oleshky, the Russians came to the house. They set up firing positions and planned to occupy the house because of its convenient access to the river. However, thanks to local resistance, they were not allowed to enter the house," says a Polina Raiko Kherson Regional Charitable Foundation representative.

According to him, the walls of the house were made of clay, so after the Kakhovka hydroelectric power station was blown up, most of the works were destroyed when the village was flooded. The museum was completely submerged. However, the ceiling and some load-bearing walls survived.

"About 20% of the house museum has been preserved. We have been in contact with an American foundation that deals with art preservation after floods. They gave us a mechanism to preserve the remains of the house. However, the city's occupation makes this impossible," Semen Khramtsov says.

Kuindzhi Art Museum in Mariupol

The Kuindzhi Art Museum was opened on October 29, 2010. Its collection includes 2,200 works of painting, graphics, sculpture, decorative and applied arts from various art schools in Ukraine. The museum's exhibition includes works by Ukrainian artists Mykola Hlushchenko, Tetiana Yablonska, Mykhailo Derehus, Ivan Marchuk, Ivan Aivazovsky, Arkhip Kuindzhi and his students.

On March 21, 2022, the museum was destroyed by a direct hit from a Russian air strike. At the time of the bombing, Arkhip Kuindzhi's original works were not in the museum. However, the fate of other artworks is still unknown.

"The Kuindzhi Museum was the centre of artistic and cultural life in Mariupol. It was active in exhibition work. There were always different exhibitions. It was a cosy corner of culture, where students from art schools often came to paint,"

says Oleksandr Hore, an employee of the Mariupol Museum of Local Lore, which was subordinated to the Kuindzhi Museum.

The works in the museum were not evacuated after the start of the Russian full-scale invasion. In particular, this was due to active hostilities in Mariupol on February 24. Only a few works were hidden from the Russian military. However, the Russians were able to obtain the paintings through the cooperation of some of the staff.

"The museum was badly damaged by shelling, but most of the exhibition survived. Especially the original works by Kuindzhi. These paintings were in the basement, so they were not damaged," recalls Oleksandr Hore.

In 2022, the Russians took almost all the paintings to other temporarily occupied regions of Ukraine, says Oleksandr Hore. What happened to the paintings after 2024 is unknown.

"The Russians published information that the paintings would allegedly return to Mariupol only when their so-called 'reconstruction' of the museum took place," says Hore.

The museum's team has already set up a virtual website to show how the museum looked before the full-scale invasion.