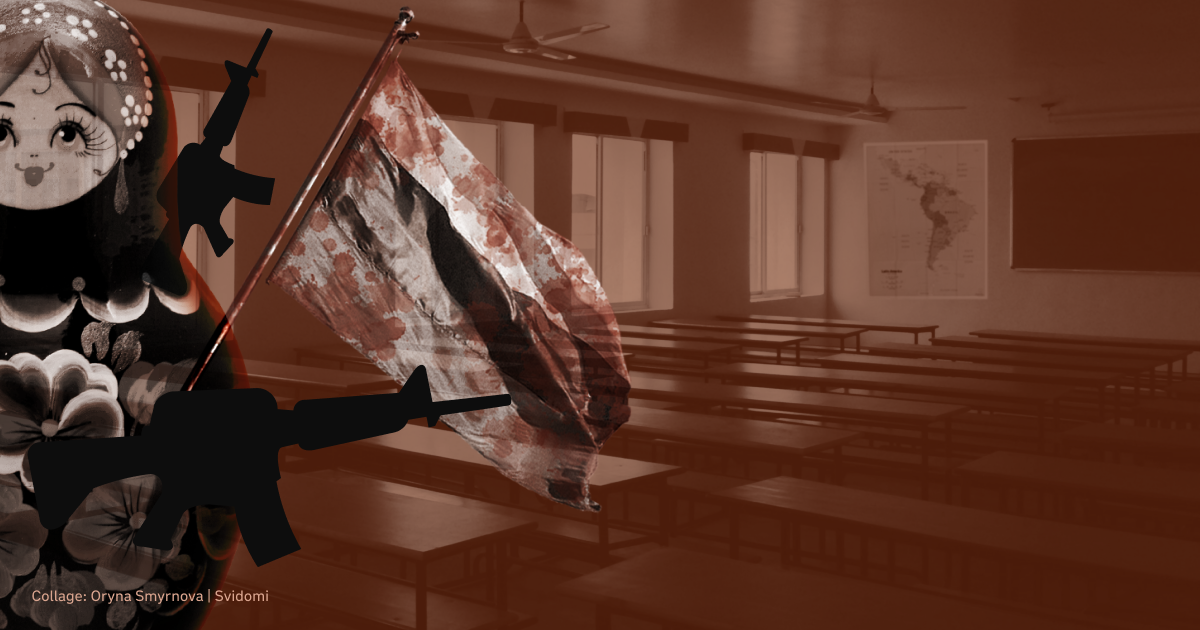

The latest attempts to exert influence: how the Kremlin's ambitions collide with reality in Latin America

With the legacy of the Soviet Union, Russia continues its efforts to increase its influence in Latin America. It is building its presence through support for authoritarian regimes, arms sales, and economic ties. Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua are key partners for Russia, as they have strong military and political interests in the region.

Despite some progress, Russia's overall influence in Latin America is gradually waning. Public opinion is becoming less favourable to Russian narratives, and its economic presence is facing serious challenges from the US, EU and China.

As part of the special project 'How Russia Undermines World Order,' Svidomi discusses Russia's attempts to establish influence in Latin America.

Russia's role in Latin America

For a decade, the Soviet Union sought to gain a foothold in Latin America. And it did. The last attempt, in Cuba, almost cost humanity the destruction of the then superpowers in a nuclear war. Now the Russian Federation is trying to continue the policy of the USSR. It is impossible to call these attempts anything other than mere efforts.

Latin America is one of the largest regions in the world, including Central and South America and the Caribbean. Russia is now seeking to increase its presence in the region by exploiting historical ties and supporting authoritarian regimes.

Latin America itself is one of the world's largest regions. It consists of the countries of Central and South America and the Caribbean. Russia's presence in the region is established in only three countries: the aforementioned Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua. By coincidence, these are the most authoritarian states in the region. Even more coincidentally, Russia is the main exporter of arms to these countries. 100% of the arms supplied to Nicaragua and Cuba, and over 85% to Venezuela, come from Russian factories. Russia continues its clear strategy of supporting anti-democratic regimes in order to prevent their complete diplomatic isolation and to mitigate the effects of Western sanctions.

In return, these states provide the Russian Federation with єa window of opportunityє to spread its influence in Latin America. Deutsche Welle reports that the Russian navy has unrestricted access to the ports of these states, and there are permanent Russian military contingents in Nicaragua and Venezuela. Since 2017, the Russian Interior Ministry has been running a centre in Nicaragua's capital to train local police and security personnel. This is ostensibly to combat drug trafficking. In reality, the training itself focuses on surveillance and repression of civilians, according to Confidencial. Officers from dozens of countries in Central America and the Caribbean have attended the training.

Russia's influence goes beyond these three countries. Its main goal is to maintain 'neutrality' and 'active non-alignment' in the Russia-Ukraine conflict among Latin American democracies. Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has blamed Ukraine for Russian aggression, Politico writes. At the same time, former Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador invited Russian troops to the country's Independence Day parade last September. Moreover, Latin America has not joined the international sanctions regime against Russia. Only Chile and Costa Rica (whose policies are largely dependent on the United States) have imposed restrictions on Russia, according to Ponars Eurasia. All this creates the illusion that Latin American states are unequivocally supporting Russia, that Russia is making progress in luring them to its side, and that the region is lost to the West and Ukraine. However, this is not the case.

At the same time, most Latin American countries condemned Russia's full-scale invasion. The vast majority of countries in the region also voted in favour of UN Security Council resolutions condemning Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Fewer Latin American countries voted against, abstained or skipped the vote in 2022 than in the 2014 vote condemning the 'annexation' of Crimea (Qırım). There were 20 such countries in 2014, but only five in 2024, three of which are Russia's long-standing allies in the region.

A similar trend can be observed in support for Russia among ordinary Latin Americans. The Russian media outlet RT Spain was launched in 2009, second only to the Arabic outlet and ahead of the American one. It is responsible for spreading Russian narratives throughout the Spanish-speaking world. Despite this, Russia's reputation in Latin America has deteriorated over the years and this trend is continuing, reports La Nacion. According to a survey conducted by Latinobarómetro before the war in Ukraine, only 19% of Latin Americans had a positive image of Russia, compared to 47% for the United States.

Russia's vaccination diplomacy during the COVID-19 era had mixed results and failed to halt Russia's declining reputation. The war finally destroyed what was left of Moscow's image. The Gallup World Poll of 2022 showed that Latin America was second only to Europe and North America in terms of average disapproval of Russia. Moreover, Latin America has seen the sharpest decline in Kremlin approval of any region surveyed since the outbreak of full-scale war. More than 60% of the region's population has a negative view of the Putin regime in Russia.

The aforementioned arms exports are usually a powerful tool for Russia to build sympathy for foreign militaries. Svidomi has already described how Russia is using this tool to support the juntas of Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso in the article Russia's colonial ambitions in Africa: How is Ukraine trying to resist the expansion?

However, Moscow has failed to use this leverage to expand its presence in Latin America. Russia has failed to capture the emerging markets of Brazil and Chile, the only two countries with large-scale military modernisation programmes, SIPRI reports. Regular customers in the region, such as Cuba and Venezuela, have suspended purchases from Moscow in recent months. Some countries have also begun to look for substitutes for Russian security goods and services.

The main players in the Latin American market are still the US, the EU, and now China. In this confrontation, Russia has little room for favouritism among the states of the region. However, it uses these states for its purposes, even if they do not express a desire to be allies of the Russian Federation.

A breath of fresh air amid sanctions and isolation

One of the main ways in which Russia is trying to use the countries of the region is to circumvent sanctions and fill the budget with hard currency. Russia has not succeeded in the former: The US cuts off any similar attempts. Russia succeeds in the latter, but not in the way the Russians would prefer.

In 2023, Brazil significantly increased its purchases of Russian oil products, becoming the largest buyer of Russian diesel in the world. The Financial Times reports that Brazilian imports soared by 4,600%, or from $95 million to $4.5 billion. The increase came amid a complete EU ban on Russian oil products and a significant drop in imports from Türkiye. Several countries in the region, notably Argentina and Brazil, and to a lesser extent Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico and Peru, remain important export markets for Russian fertilisers.

Rosoboronexport is the state intermediary agency for the import and export of military technologies and services. Rostec is a state corporation that promotes the development, production and export of industrial products. These two state enterprises are the backbone of Russia's military cooperation in the region and the budgetary flow of dollars in exchange for arms. Equipment sold and loaned by Russia ranges from fighter bombers and aircrafts to warships and tanks, Atlantic Council writes.

Rosatom (Russia's State Atomic Energy Corporation) is currently active in Bolivia and Argentina with research and nuclear power reactors. Rosneft, the Russian state oil company, is active in many countries: Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador and Colombia. Russia's RUSAL is the world's second largest aluminium company and has a growing presence in the Caribbean. At the same time, there are also failed cases of Russian economic presence. Gazprom, present in Bolivia since the 2000s, failed to expand its operations; its local offices remained empty until 2022.

Brazil is the only BRICS member in Latin America. This helps Russia to make its voice heard on international platforms and in Latin America. At the same time, it should not be assumed that Brazil's participation in BRICS makes it an ally of Russia. BRICS is increasingly becoming an organisation of China and India, not Russia.

However, Brazil has tried to bring Russia out of its international isolation. Former President Lula had previously expressed his desire to host Russian President Putin at the G20 summit in November 2023, despite the arrest warrant issued by the International Criminal Court. At the time, this step was not taken for fear of a possible backlash. Instead, it happened in Mongolia in 2024. Read more in Svidomi's article Putin challenges the International Criminal Court. Who will take responsibility for Mongolia's failure to arrest the dictator?

Russia's ability to be present in the region and to engage in economic activities is significantly hampered by its lack of involvement in the region's institutions, unlike China. Russia has never been a partner in the Organisation of American States or the Inter-American Development Bank. The reason for this is that the headquarters of these organisations are located in the United States, and the influence of the United States on all decision-making in the organisations is considerable.

Three Horsemen of Russia: Propaganda, Disinformation and Espionage

As mentioned in the previous article, Russia is actively trying to spread its propaganda in Latin American countries with the help of Russia Today Spain. These attempts do not seem to be successful. Disinformation campaigns based on Russian models accuse Ukraine of using actors as civilian corpses in de-occupied cities. It is claimed that the US and NATO "planned the war in Ukraine". And, more recently, that Ukraine is selling arms to Hamas. Such narratives are not very popular because, unlike Russia's propaganda narratives in Africa, they do not resonate with the people of the region. All RT outlets are currently banned in Costa Rica and Uruguay.

Lacking popular support, the Russians are turning to more exotic methods of disinformation and propaganda in Latin America. The Wilson Centre argues that Russia is expanding its cooperation with media universities in the region to train their students on its territory and introduce propaganda 'on the ground' in 'transponders'.

For example, presenters on Deutsche Welle's Spanish-language programmes often fail to correct their guests who repeat Moscow narratives such as the "administrative borders of the Russian Federation". That is, the narrative that the borders of the occupied territories of Ukraine are the borders of Russia. France 24, and in particular its Spanish-language division, provides an opportunity for Moscow's influencers to speak on its media platforms and repeat the Kremlin's official narratives. Examples include presenting the withdrawal of Russian troops from parts of the occupied territories in 2022 as a 'goodwill gesture', justifying the invasion as the protection of the Russian population in the Donetsk region, and questioning the legitimacy of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

Russia is making direct inroads into Latin American universities. A recent example of this trend is a textbook on comparative foreign policy published in Mexico. It is intended as a standard textbook for Mexican students of international relations. While many of the chapters provide valuable, independent analysis by Mexican and international scholars, the chapter on Russian foreign policy contains no such analysis.

Written by a graduate of the Patrice Lumumba Peoples' Friendship University of Russia, the textbook claims that "there was direct US intervention in Ukraine to organise the coup that ousted the Europeans in February 2014" (p. 287). It argues that "the conflict initially appeared to be a quick fix, but when the US and EU began sending arms to Ukraine, it escalated into a NATO-Russia confrontation fought on Ukrainian soil" (p. 287). The chapter also avoids using the term 'war' to describe the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Instead, the terms 'special military operation' and 'conflict', favoured by Kremlin propagandists, are often used. This approach allows Moscow's official narratives to appear under the guise of academic analysis aimed at young Mexicans.

Last but not least, Russia's influence in Latin America is espionage. Yevgeny Prigozhin's 'offensive' against Moscow on June 23, 2023, overshadowed an event about which The Insider published a report. The report stated that Russia was reopening its Lourdes spy base in Cuba. Closed by Putin himself in 2001, this station played a major role in Russia's spying on the United States during the Cold War. It has been virtually inactive since 1991. Latin America is a well-developed region for Moscow's intelligence services. Faced with the dismantling of its spy networks in Europe, Moscow is mobilising dormant cells in Latin America.

Mexico has become the centre of this activity. The Associated Press reported that in 2022, a US general named Mexico the country with the largest number of Russian intelligence officers stationed abroad. In 2023, The Insider reported that Mexico served as a transit point for Russian intelligence to Cuba. The head of the Cuban base (intelligence station abroad—ed.) also previously headed the Mexican office.

In addition to agent-based intelligence, Moscow is actively using electronic intelligence throughout the region. Brazil and Nicaragua have several GLONASS ground stations (Russia's alternative to GPS) that are operational and kept secret. The Nicaraguan station, located in Managua, is suspected of monitoring the communications of the local US embassy. New stations are to be built in Argentina, and Mexico signed a cooperation agreement last year with GLONASS (a Russian satellite navigation system operating as part of a satellite radio navigation service with active ground stations in Brazil and Nicaragua) (although the Mexican government categorically denies opening a new station on its territory). Similarly, the Russian military operates six radar systems in Venezuela, designed to improve the regime's surveillance of the domestic opposition and military manoeuvres in neighbouring Colombia.

When to be afraid?

Despite its extensive involvement in Latin America, Russia is not achieving its goals. Unlike the United States, Europe or China, Russia cannot rely on economic influence to secure its position in Latin America. With few exceptions, Russian trade and investment have been stagnant and declining since the late 2010s. Even then, Russia was struggling to find a viable regional hub for its commercial interests, with neither the large Brazilian economy nor the sympathetic Venezuelan regime able to fill the role.

Russia has not been able to achieve its goals of media domination of the region. On the contrary, the rate of decline in sympathy among the local population is now at its highest. In such a situation, Russia is forced to resort to more expensive and exotic methods of propaganda and disinformation and to expand its agent networks.

Latin American governments themselves are not unequivocal in their support for the Kremlin. On the contrary, Argentina, which was supposed to be part of the BRICS, has completely turned its foreign policy towards the West and the support of Ukraine. Argentina's President Javier Milei, who was elected in December 2023, planned to transfer Argentine fighter jets to Ukraine and also intended to hold a summit of Latin American countries that support Ukraine and reject Russian aggression. Unfortunately, these ideas have not yet been implemented, but they indicate a paradigm shift in Argentina's foreign policy.

Agreements with Moscow's close regional partners (Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua) may not be possible in the short term. But Latin America as a whole should not be ignored. Jordan, Sudan, and Morocco's experience shows that there are ways to persuade countries in the Global South to support Ukraine, albeit subtly and within their means. As votes in the UN General Assembly or opinion polls show, Ukraine and its Western partners have room to work directly with Latin American governments and their populations.