The fate of Crimean Tatar art and culture amid imperial ambitions

Oleksandra Bobukh

"The Black Age"

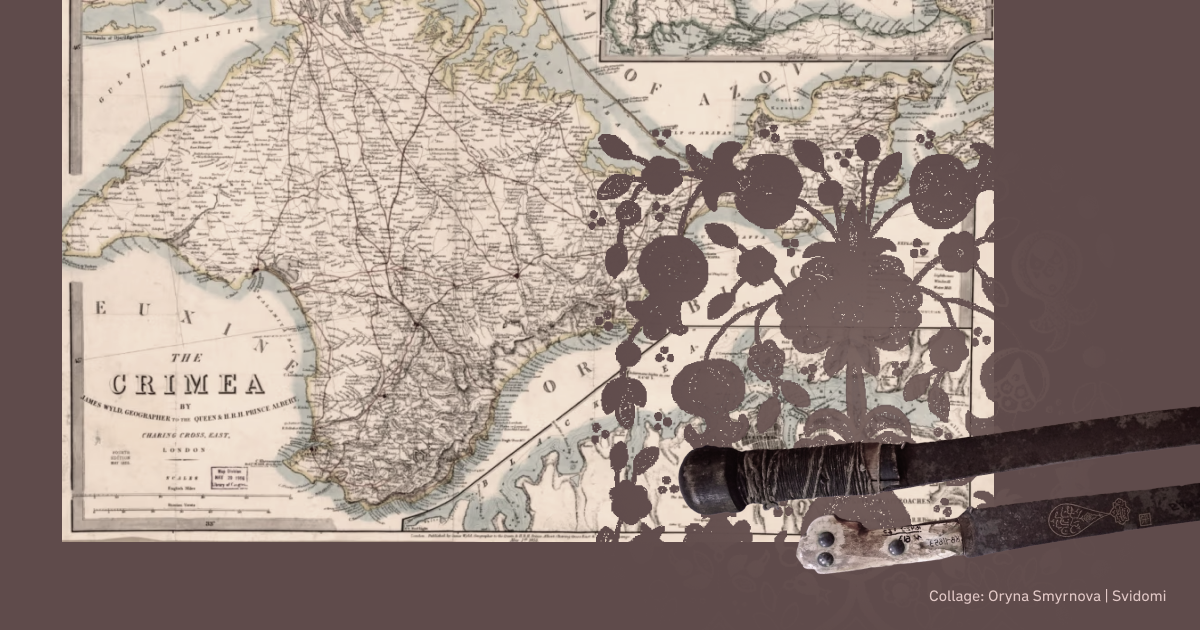

In July 1774, the Russian and Ottoman Empires signed a treaty of "eternal peace", known as the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca, granting the Crimean Khanate independence. The treaty obliged Russia to withdraw its troops from Crimea (Qırım), but it retained key positions that ensured its influence on the peninsula.

Despite resistance, the peninsula was annexed in 1783. The Russian Empire introduced a policy of forced evictions, land confiscation and the transformation of free peasants into serfs.

There was a decline in cultural life: many ancient manuscripts and books were barbarically burned, and many historical and cultural monuments were destroyed. Mosques, madrassas (schools), caravanserais, and cemeteries were destroyed, and the remains of ancient traditional buildings were preserved only in a few cities.

For example, the unique monument of the Eshil-Jami of the Bakhchysarai Palace ("Green Mosque"), painted by Omer, a prominent painter who lived and worked in Bakhchysarai (Bağçasaray) in the 18th century, was almost completely destroyed in the early 20th century.

The crescents, symbols of the Crimean Khanate, were replaced by two-headed eagles, and the Bakhchysarai Palace (Khan's Palace — ed.) was handed over to the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Empire.

says Elmira Ablyalimova-Chyihoz, project manager at the Crimean Institute for Strategic Studies and former general director of the Bakhchysarai State Historical and Cultural Reserve and add.

"Almost a year later, the first repairs and reconstructions began, during which the Bakhchysarai Palace significantly lost its authentic style. At the end of the 18th century, it was transferred to another department, and a new series of repairs and reconstructions began, further changing the complex. By the end of the nineteenth century, 70 buildings had been declared dilapidated and demolished."

The Soviet period

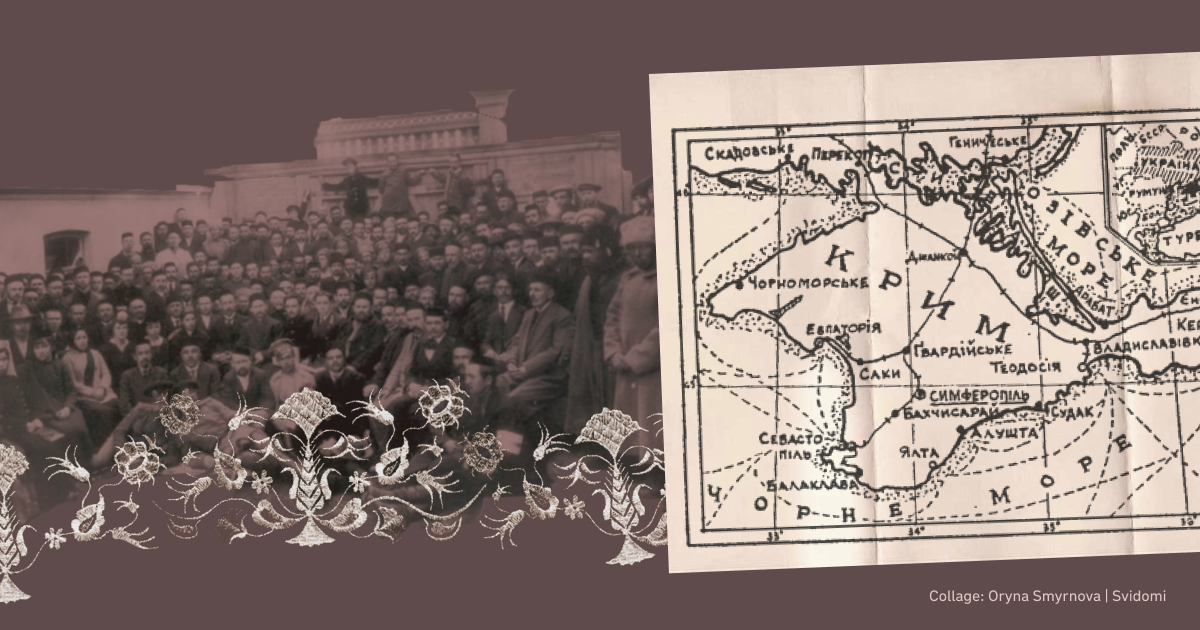

In 1917, the Crimean People's Republic was established in Crimea.

"It is very important to note that it was the first Muslim democratic republic in the world to recognise, tolerate and grant equal rights to representatives of religions other than Islam and nationalities other than Crimean Tatars. And the constitution of thе republic also established the equal right of men and women not only to vote in elections but also to be elected,"

says Crimean Tatar journalist and human rights activist Alim Aliev.

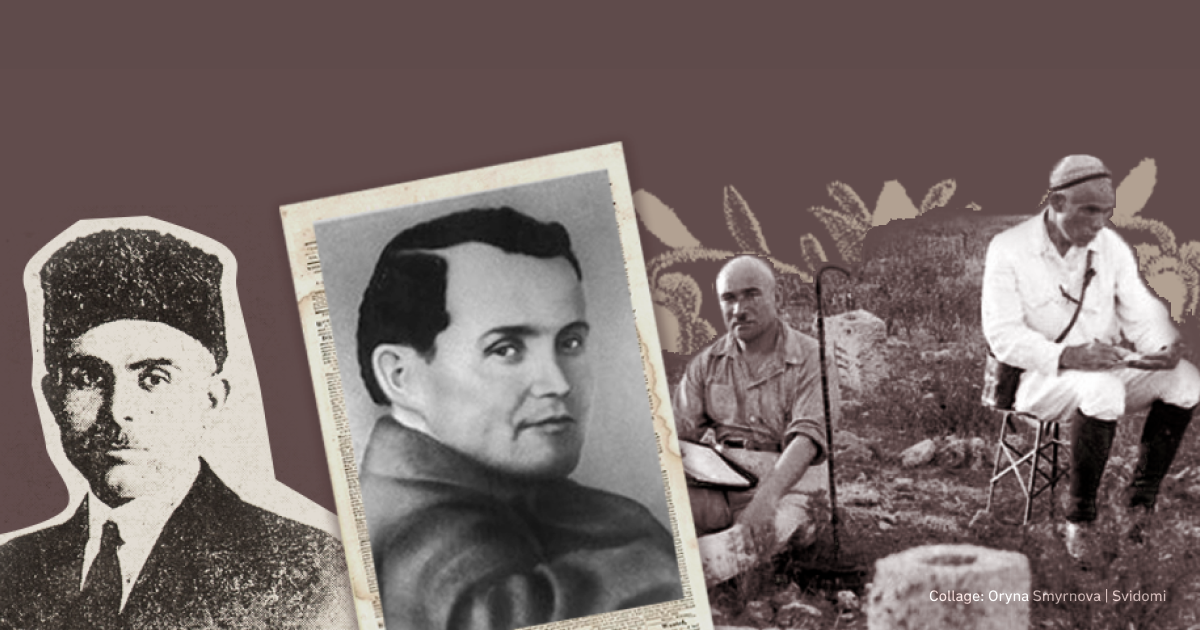

But in 1918, the Bolsheviks killed the Crimean Tatars' leader, Noman Çelebicihan. Later, in the 20s and 30s, the process of Tatarisation continued. The study of Crimean Tatar history and culture began. National schools were established, books were published, theatres were founded, and traditional crafts were revived.

The most massive and bloody repressions took place in 1937-1938. On April 17, 1938, the communists killed dozens of prominent representatives of art and culture, education and science, and political and public figures. Due to the large number of people sentenced to death, the executions lasted three days. The list of those accused of "espionage" included 41 Crimean Tatars: 36 were killed, and five were sentenced to long-term imprisonment.

But the shooting of the intelligentsia was a prelude to the global tragedy that took place six years later — the deportation of the Crimean Tatars on May 18, 1944. In three days, 200,000 people were deported in cattle wagons. More than 46% of the deported Crimean Tatars died as a result of the inhumane transport conditions and in the first years after the resettlement, including the famous ornamentalist Adaviye Efendiyeva, who worked in the ornek technique.

Preserving culture in the face of deportation

"How did the Crimean Tatars manage to preserve their culture and language in the face of deportation without dissolving into Central Asian cultures? The answer is simple: they were driven by the mission to return to their homeland. Even though the history of deportation was forbidden, it was dangerous even to call ourselves Crimean Tatars. Nevertheless, at home, in their kitchens, the Crimean Tatars performed religious rites, held weddings, taught and passed on the language, and talked about the historical milestones of the Crimean Tatar people. In this way, they preserved generations," says Crimean Tatar journalist and human rights activist Alim Aliev.

The return took place in 1989, but even after Ukraine became independent, the culture of the Crimean Tatar people remained encapsulated. It was never possible to promote it under the pro-Russian Crimean authorities, who were unwilling and refused to do so.

The new Russian occupation

Since 2016, work that the Russians call "restoration" has been carried out on the Khan's Palace in Bakhchysarai territory.

"The technologies and materials used to allegedly 'restore' the monument do not correspond to the period of its construction and distort it, turning it into a new building. In addition, the occupation authorities do not recognise this monument as an archaeological heritage site, so the cultural layers are thrown away due to repairs and are not studied. This means the monument is losing its scientific, historical and artistic value and evidential component. In the long term, it will cease to exist as a monument,"

says Elmira Ablyalimova-Chyihoz.

The state of Crimean Tatar culture in Crimea after 2014 is currently challenging to study."It is impossible to develop fully in conditions of constant danger. It is important, at least, to preserve national integrity without losing conceptual unity, to preserve ourselves and our families physically and to minimise losses. As for persecution, it is equally dangerous for everyone in Crimea. Everyone is persecuted — young and old, people of different professions and activities," says Elmira Ablyalimova-Chyihoz.

"And to tell the truth, since 2014, Ukrainian society has reconsidered its attitude towards the Crimean Tatars, and it is clear that they are absolutely the most powerful pro-Ukrainian force on the peninsula, the most massive. And today, we are rediscovering each other,"

says Alim Aliev.