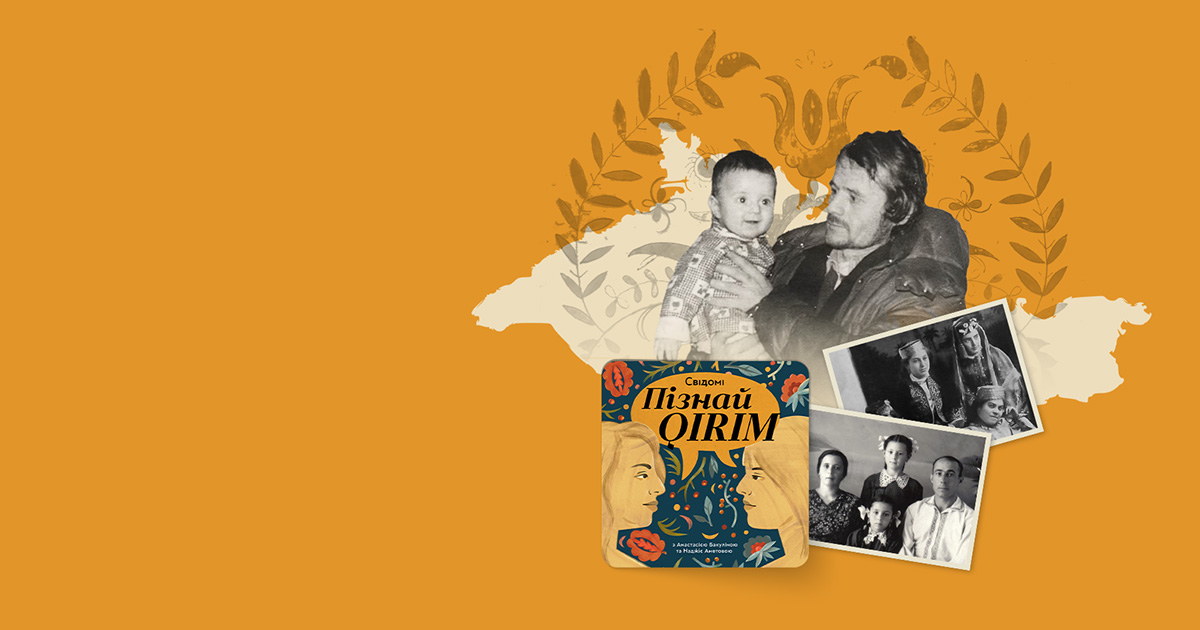

The Family

The theme of the family runs through both Crimean Tatar and Ukrainian culture. Two peoples that the imperial machine spent centuries trying to destroy through deportation, genocide and ethnic cleansing are now restoring the continuity of their family line. Who else but family is the driving force behind this restoration?

In the fourth episode of the Discover QIRIM podcast, we will dispel the stereotypes that have formed around this topic, as there is still a distorted view of the role of women in society or in raising children.

Stereotypes about women and the Crimean Tatar family

The most common stereotype is that Crimean Tatar women have no voice in the family. "This has nothing to do with us," says Nadzhiie Ametova.

"Crimean Tatar women are usually wise. Some are very loud, and others are grey eminences.

Even if it looks quite traditional, it is up to the women to make the decision.

It may be formally articulated by her husband, but it is the woman who will speak and lead this process.

Violence is possible in Crimean Tatar families, just like in any other family, but unfortunately, it is a 'taboo' subject, the same as in Ukrainian culture.

Marriage in Crimean Tatar culture

Crimean Tatar women do not often marry men of other nationalities. The issue of mixed marriages is one of the most sensitive in the Crimean Tatar community. It is an issue of a people who wants to preserve themselves. Therefore, there are formal frameworks in the discourse that are discussed, which are sometimes misunderstood by those who are not Crimean Tatars. We live in a globalised world now, you know.

"But this is a really serious issue for those who care about the fate of the people. Because we are very few. We are becoming fewer and fewer. And now, especially since 2014, and later 2022, we are all scattered not only around Ukraine but also different parts of the planet," Nadzhiie says.

A child born into a family where all the members are Crimean Tatars will have a clear understanding of his or her identity: "A person will identify oneself distinctly as a Crimean Tatar man, a Crimean Tatar woman."

The concept of marriage in Ukrainian families

There is no single rule, it all depends on the continuity of the family. Podcast co-host Anastasiia Bakulina tells us about a friend who married a man from the Sumy region (bordering Russia to the north) and did not take his surname because it had been Russified (many families have stories of how Ukrainian surnames were Russified by adding typical Russian suffixes such as -ov, -ev or -in to make them conform to the 'correct' and 'official' Russian tradition — ed. ), and her grandfather was a soldier in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (a Ukrainian nationalist paramilitary and partisan formation engaged in guerrilla warfare against Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union — ed).

"For example, in my family," says Anastasiia, "there is no continuity. Firstly, my surname is Bakulina, and secondly, there are no such traditions. That is to say, there is nothing that is passed on from generation to generation: neither traditions nor certain things. If I had such a family, or if I had such an opportunity, if I married into a family with such a continuity of tradition, I would keep that continuity. It's a beautiful thing, really.”

Principles and compromises in family life

Religion is also important in family life. The artist Elzara Halimova recalls the following story: "...they told with horror about an old man whose wife was Slavic, and she buried him in a coffin. But Crimean Tatars do not bury people in coffins. Her husband had told her that he should be buried according to Muslim traditions."

Yet, both Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar cultures share a certain conservatism. For example, in Halychyna (a historical region in the west of Ukraine — ed.), girls are always told they cannot have intimate relations before marriage because no one will marry them.

Feminism in Crimean Tatar culture

Speaking of Crimean Tatar history, the first Kurultai (traditional institution of higher state power — ed.) had a woman in it — Şefiqa Gaspıralı (Gasprinskiy), the daughter of Ismail Gasprinskiy, the prominent Crimean Tatar enlightener.

Gasprinskiy's wife came from a wealthy family, and it was she who economically supported the existence of the newspaper Terdzhiman (The Translator, the first Crimean Tatar newspaper, published from 1883 to 1918 — ed.)

Many women were also among the dissidents and activists of the resistance movement.