Soviet deportations are a crime against humanity

Andrii Kohut

On March 22, 2022, The Times published the news under the title "Russia plans kidnapping and violence in ‘great terror’ to end Kherson protests". It was an information leakage from a person whose previous involvement with the FSB was confirmed. The Russians were prepared to use mass deportation of Kherson residents because they could not suppress the mass protest against the occupation.

It is one of the first reports of deportations since the start of the large-scale Russian invasion. Afterwards, journalists and researchers alike repeatedly appealed to the "history repeating itself", noting that the Russians were once again forcibly evicting Ukrainians, just as the Soviet and Russian imperial regimes did.

While modern Russian crimes against humanity are still awaiting proper assessment and analysis, similar Soviet crimes have been relatively well studied.

Although the first Communist deportations date back to 1918-1920, they became widespread in 1929 and were actively used until the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953.

What are the features of deportation?

Researchers have identified a number of features standard to all deportations as a form of political repression. First of all, they are coercive. The deportation process was planned so people could not avoid eviction. Resettlements were also forced, partially or wholly, although they were declared to be voluntary.

The extrajudicial, administrative nature is another common feature. Decisions on forced evictions were made administratively, outside the legal framework established by the Soviet regime. As a rule, these were party bodies of various levels and/or repressive bodies: the police and the so-called state security agencies.

The next feature is the directive definition of the contingent, i.e. the group to be deported. At the same time, it could be the forced deportation of an entire group, such as certain people (deportation of the Crimean Tatars), or the definition of the principles according to which the contingent should be selected.

An important feature is planning. Mass deportation operations were planned in particular detail. Sometimes, it was made so detailed that they considered the need to provide for the overfulfilment of the plan.

This "overfulfilment" was achieved quite simply. For example, during Operation West, the leadership of the MGB (the Ministry of State Security, as the communist secret services were called in 1947) submitted a plan to the Communist Party that indicated the deportation of 25,249 families and another number of families scheduled for deportation, 27,510, were "sent down" to the regions. As a result of the operation, 26,332 families were deported, which allowed the MGB leaders to report on the successful implementation of the plan to the Communist Party.

Attempts to solve the problem of labour shortages in "remote areas of the Soviet Union" by actually forcing the deportees to work as slaves is another characteristic feature.

At the same time, the victims of forced deportations were sent mainly to work in entirely different climatic conditions and to perform completely unusual, often hard labour. For example, peasants from Ukraine were sent to work in mines and heavy metallurgy plants in Siberia and Kazakhstan.

Types of deportations

Soviet deportations were carried out in the format of three types of forced evictions: actions, operations, and campaigns. Under deportation operations, researchers understand the mass deportation of a fixed contingent in a particular territory within a planned short period.

Deportation actions are forced evictions as one of the permanent measures of repression of a certain contingent for a specific purpose (cleansing of the "hostile element" or terrorising the civilian population to destroy support for the resistance).

It is essential to distinguish between the "language" of the documents and the research typology since the Chekists used the term "operation" both for the eviction of several families and for a mass event.

Numerous deportation actions and operations that are chronologically and geographically separated but share the same contingents and/or key tasks are grouped by researchers into deportation campaigns.

The kulak deportation was one of the most extensive campaigns. The deportation of wealthy peasant families who were considered enemies of the communist regime on social grounds began in 1930 and continued, with interruptions, until 1952. Forced evictions were an element of the destruction of the kulaks as a class and one of the essential elements of accelerating collectivisation.

On January 18, 1939, the OGPU (Joint State Political Directorate — ed.), signed by Henrikh Yahoda, sent out a directive to prepare for the eviction of kulaks. The "counter-revolutionary activists" were to be deported to remote areas of the USSR, and the rest of the wealthy peasants were to be resettled in locations outside the collective farms. At the same time, the vast majority of the dekulakised people's property was confiscated.

Forced deportations began in February 1930.

As a result of several waves of deportations in 1930-1931, 63.7 thousand families were forcibly evicted from Ukraine. More than half of them were deported to the Urals (32.1 thousand families) and another 20 thousand to the Northern Territory of the Russian Federation. Ukraine ranked first among other subjects of the Soviet Union (this does not include those deported from Crimea) in terms of the number of deported kulak families.

The deportees were resettled in so-called "labour settlements", and in the documents of the repressive authorities, they were called "labour settlers".

Forced evictions continued in the following years. The historiography of the evicted kulak farms is estimated to be over 200,000 households.

Ethnic deportation

In the mid-1930s, ethnic deportation was added to social deportation. Poles and Germans living in the western regions were evicted as "politically unreliable". The first wave in 1935 involved the deportation of Poles and Germans from the then border regions of Vinnytsia and Kyiv to the eastern regions of Soviet Ukraine (8,329 families or 41,650 people), and the next wave to Kazakhstan. In 1936, 14,048 families were deported there.

With the beginning of World War II, deportations were first used to "cleanse" the newly occupied territories of "enemy elements". During 1940, four mass operations were carried out one after the other: 1) on February 10, operations were launched to evict Polish settlers and foresters (17,203 families or 89,079 people); 2) the minor operation was the second wave on the night of April 8-9, when 737 former prostitutes were deported; 3) families of previously repressed residents of western Ukrainian regions were evicted on the night of April 13-14 (10,475 families or 32,076 people); 4) the last operation began in the Lviv region on June 25, and in the rest of the regions on June 28, and lasted until June 30 (61,892 to 83,207 refugees from the German occupation zone were deported).

Poles made up the majority in the first and third operations, and Jews hoping to escape the Nazis made up the majority in the last one.

In 1941, the main focus of Soviet deportations was on so-called "counter-revolutionary organisations". First and foremost, the families of OUN (Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists — ed.) members, with the families of Polish and Jewish underground members being the second and third priority.

Thus, the last mass operation from western Ukraine began on May 22, 1941, and out of 11,329 people, the majority were Ukrainians. It is significant that the Resolution of the Central Committee of the CPSU and the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR, which regulated the deportations, ordered to consider similar measures in Soviet Belarus.

Forced deportation, in this case, was a tool to combat underground Ukrainian and Polish organisations. Ethnic Ukrainians accounted for approximately 14-15% of all deportees from western Ukraine in 1940-1941.

On the night of June 12-13, 1941, a deportation operation to evict "counter-revolutionaries" was carried out from the newly annexed Izmail and Chernivtsi regions of the Ukrainian SSR and Moldova. A total of 29,839 people were seized, of whom 24,360 were evicted (3,615 and 7,611 from the Ukrainian regions, respectively), and the rest were arrested.

The locations of all deportations during the first period of World War II, when the Soviet Union was an ally of the Nazi Third Reich, were typical: northern Russia, the Urals, Siberia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan.

In the second phase of World War II, the main victim of preventive deportations was the German population. In September 1941, deportations began from Zaporizhzhia, Stalin, and Voroshylovhrad regions (approximately 110,000 people), and in 1942 — from Kharkiv, Odesa, Dnipropetrovsk, and Crimea (Qırım) (the number is unclear).

After a short break due to the German occupation, deportations resumed with the return of Soviet control over the territory of Ukraine. The range of those who were subjected to the so-called retaliatory deportations was quite wide and included both entire nations and individual groups.

Forced evictions of the latter contingents, such as former police officers, "Vlasovtsy" (former soldiers of the army and Russian collaborator units), Volksdeutsche and other categories of people classified as traitors to the Soviet homeland, continued after the end of the World War II.

Total deportation was applied to the so-called traitor nations. In addition to Germans, other unreliable nationalities were also included.

Deportation of Crimean Tatars in 1944

The largest mass operation of this type was the deportation of the Crimean Tatar people. During the period of May 18-20, 1944, 191,044 people were forcibly evicted, and Crimea (Qırım) was "cleansed" of its indigenous people. Notably, the self-census conducted by the victims of the operation themselves indicates twice as many — 423,100 people.

After the deportation of the Crimean Tatars, in June of the same year, Bulgarians (12,628), Armenians (9,821) and Greeks (16,006) were also deported from Crimea (Qırım), all accused of aiding the Third Reich.

Deportation of the UPA and related parties

The return of the communist regime to the territories occupied in the 1939s and 1940s was strongly resisted by the UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army) and the nationalist underground. To overcome this resistance, the Soviet authorities tried to use various methods. Forced eviction of families of insurgents and those who supported and sympathised with the liberation movement was one of them.

The NKVD directive of the USSR of March 31, 1944, regulated the deportation of "OUN families". Between 1944 and 1946, 36,609 people were evicted from the western Ukrainian regions.

In 1946, important institutional changes took place in the Soviet Union, and forced evictions, as political repression, were transferred from the police to the so-called state security. The MGB, or Ministry of State Security, began to use deportations on a new scale.

Probably under the influence of the Cold War and the Kremlin's demands to destroy Ukrainian insurgents, deportation practices reverted to one-time mass forced evictions. In this way, the MGB hoped to achieve the most significant effect of state terror.

The deportation, codenamed West (Zapad), was the first mass operation of the MGB. To eliminate local support for the Ukrainian rebels, 77,791 people were forcibly evicted from the western Ukrainian regions between 21 and 26 October. Three-quarters of all deportees were women and children. The majority of those evicted were families of insurgents and underground fighters who had already been repressed or died fighting the Soviet regime.

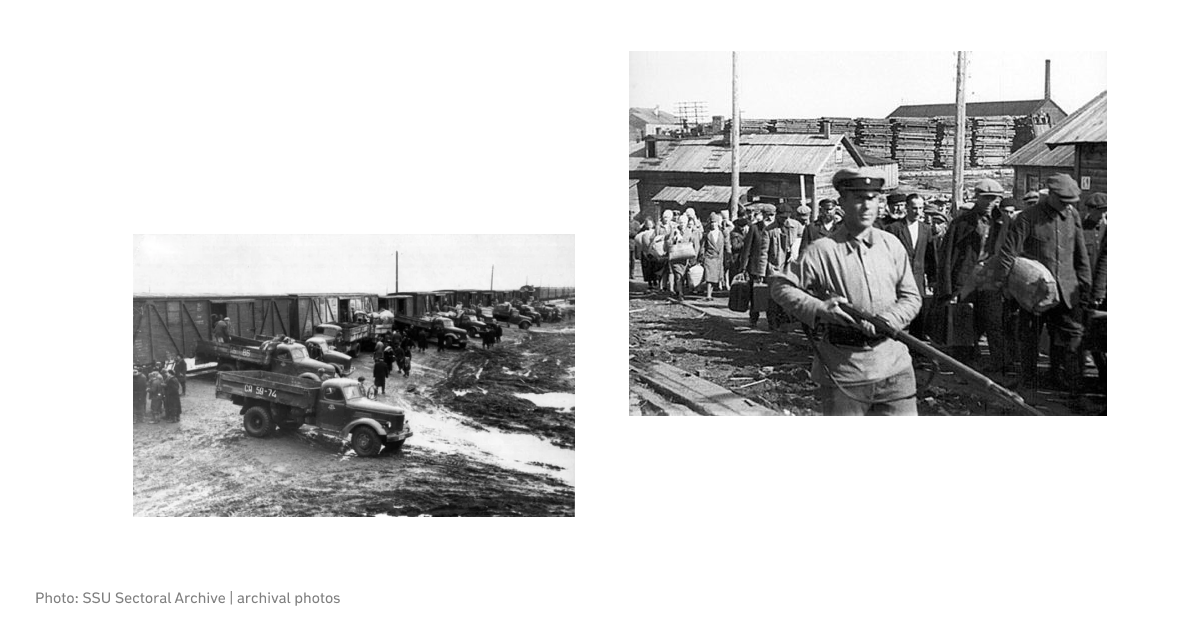

After Operation West (Zapad), the Soviet regime continued to use forced evictions as a tool of counterinsurgency. The deportation process was improved. For this purpose, particular stationary collection points were set up to accumulate victims of forced evictions before loading onto trains.

Also, from October 1948, deportation was used as a response to the actions of the insurgents. The entire civilian population was recognised as hostages. From October 1948 to 1952, another 80,209 people were deported as part of such retaliatory Soviet actions.

Deportation of those who refused to work

The deportation of "persons who persistently evade labour activity in agriculture and lead an anti-social, parasitic lifestyle" was another long-term campaign.

Initiated on February 21, 1948, by Nikita Khrushchev, the fight against collective farm evaders spread to the entire Soviet Union in June. Deportations of "parasites" continued until 1953. As a result, 33,266 peasants were forcibly evicted from Ukraine, with another 12,265 people leaving voluntarily.

Alongside the constant deportation campaigns, the Soviet regime continued to conduct operations. In October 1948, 250 "kulak"' families were evicted from the Izmail region.

Cleansing the Black Sea coast of "politically unreliable elements" was the goal of the next operation, codenamed Volna, which covered Azerbaijan, Armenia, Russia, Georgia, and Ukraine. Greek and Turkish families were deported from Odesa, Izmail, Mykolaiv and Kherson regions — 448 people were evicted during this period.

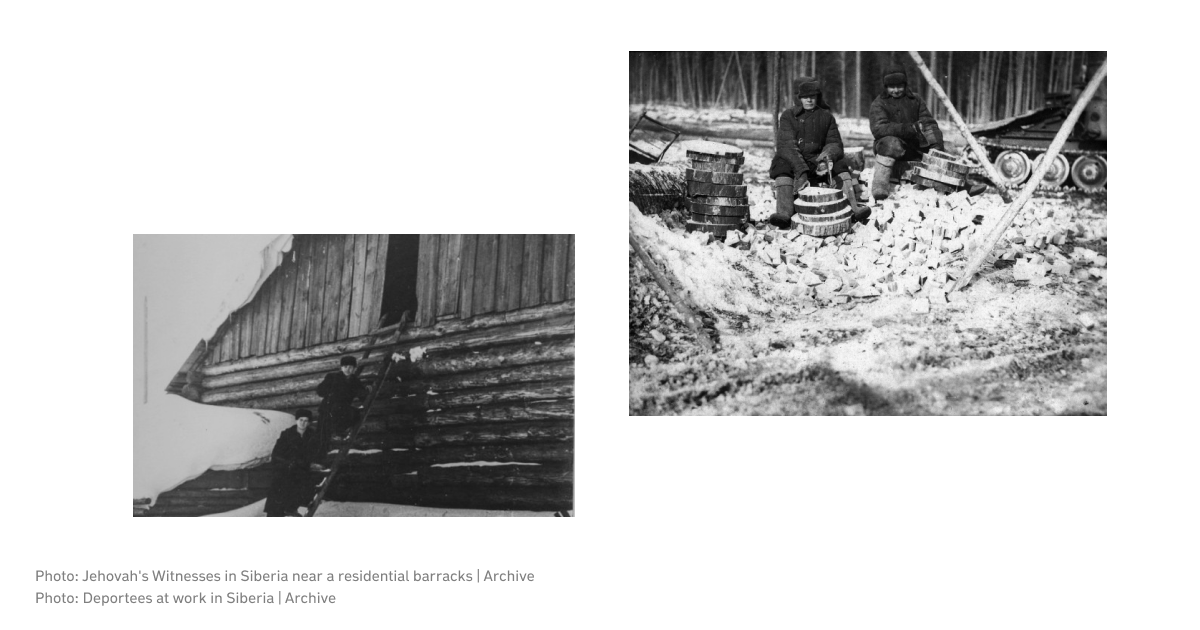

The last operation on the territory of Ukraine was the deportation codenamed Troika. On April 8, 1951, former soldiers of the Polish army under General Władysław Anders, the so-called Anders' army (1,032 people), kulaks (1,644), and Jehovah's Witnesses (6,308) were forcibly evicted.

Conditions of deportation

This is a far from complete list of all deportations. The terms used by the regime for deportees differed: labour migrants, administrative exiles, and special settlers. At the same time, the conditions in which people found themselves were almost identical.

Everyone was forbidden to leave the new places of settlement. Those who decided to change their place of residence or return home were treated as fugitives. They were searched for, caught and prosecuted.

The Ministries of Internal Affairs or State Security constantly controlled deportees. If there were suspicions that some of them were planning to escape, they could be sent further north or east. Requests for labour, which could not determine their place of work and residence on their own, were constantly received by the camp and special settlement administrations.

During the forced deportation, deportees were allowed to take a limited amount of cargo with them, which should have included food, clothing, basic necessities and household items. However, not everything reached the places of exile. There were frequent cases of abuse by escorts.

On the sites, deportees were supposed to be provided with accommodation and agricultural plots. However, in the reports on living conditions prepared by the Soviet punitive authorities, we can read that the walls of the dugouts were covered with ice, and there was no space in the barracks.

Food supplies depended on meeting production targets. It was often impossible for deportee families, which consisted mainly of women, children and older people, to meet the planned production rates. As a result, reports from the special settlements are full of information about malnutrition, dystrophy and infant mortality.

After

Ukrainian legislation recognises Soviet deportations as a form of political repression, an element of state terror. All victims of repressions are automatically recognised as rehabilitated. Children of deportees who were in exile with them are recognised as victims of repression.

Article 7 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court defines deportation as a crime against humanity.