"Small people with big hearts": the story of a Kherson volunteer who survived captivity

Yelyzaveta Kamenieva

In late February, after the start of the full-scale Russian invasion, Kherson activists launched volunteer activities in the city. There was no intimidation by the Russian authorities during the seven months of work, but at the end of September, the military came to the volunteers, put sacks on their heads, and took them to a torture chamber. Journalist Yelyzaveta Kamenieva spoke with the coordinator Olha, who spent 14 days in Russian captivity, but the other names are withheld for security reasons.

At first, the group of activists consisted of six people, but the number of those willing to help gradually increased. Volunteers purchased produce, baby food, diapers, and medicine and delivered them to addresses. Canned food, butter, porridge, tea, cookies, sugar, cereals — at first, food packages were like this. It all depended on the number of donations. Later, people indicated what exactly they needed. For example, vital medicines or lactose-free baby food. If there was a need, volunteers went to neighboring Mykolaiv for purchases.

Not only residents of the city but also the villages of the region received help. People either asked for help themselves or their relatives called from other cities. Volunteers created lists of phone numbers, and during mass distributions indicated only the last three digits for safety. Volunteers handed out up to 200 packages per day.

"It was difficult at the end of February. Pharmacies were closed, and there was no access to medicine or baby formula. We actively searched and called friends. Later, the occupying authorities began to control shops and markets — Kherson residents had to pay them to rent a place in the market. Later, only Russian products and medicines were brought to the city, so we had to buy their goods," Olha recalls.

Some people did not leave their houses at all, so humanitarian aid was brought to their homes. Those who were able to come were notified by phone about the day, time, and place of distribution. The complete lack of a phone signal made work difficult. Then volunteers delivered only to already known addresses. Difficulties also arose when it was necessary to report to the public organizations which volunteers gave the volunteers donations. Purchase reports had to be sent in the form of receipts. When there was no Internet in the city, the receipts-issuing terminals did not work either. The sellers wrote by hand what was bought and in what quantity.

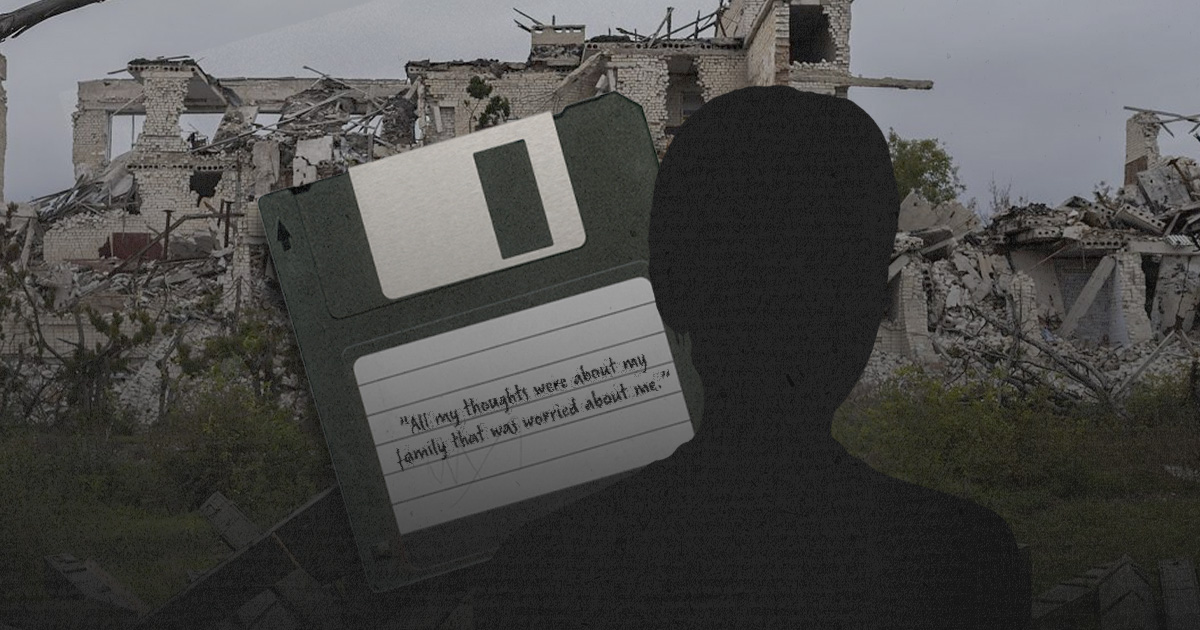

"There were no threats or intimidation from the Russian army, but there was always a feeling that they could find and punish us," the volunteer shares. And so it happened. In September, armed soldiers broke into Olha's house, where Kherson residents organized charity activities. They put bags on the heads of three volunteers, loaded them into cars, and took them to an unknown destination. Olha did not understand where she was and whether she would get out of there alive.

"All my thoughts were about my family that was worried about me. The neighbors saw us being taken out of the house, so they called them right away. My mother and grandmother also lived under occupation, so they knew about this life firsthand. However, no one knew what captivity was like," the volunteer recounts.

On the first day of captivity, Olha was accused of pro-Ukrainian position and volunteering. The military emphasized that the city had become Russian, therefore the aid should be Russian. Ukrainian volunteers could not work without the permission of the occupation authorities. For this, Olha was undressed, beaten, tied to a table, and a gun was put to her head. After several interrogations, the woman was forced to record a video in which she had to praise the Russian government and support the so-called "special operation." To fake a good picture, the woman should have been with no bruises on her face, so they began to punish her differently: clamps were put on her ears, water was poured on her, and she was electrocuted. When the volunteer refused to record the video, she was beaten again and taken to a cell, which was mockingly called a "hotel."

A few days later, the Russian federal services found out that Olha has a law degree, so they came up with a new charge — assistance to the police, cooperating with Ukrainian security services. They also searched the woman's phone for military contacts. They put pressure on her, threatened to kill her, and constantly asked if she was scared. "Sometimes I had to pretend to be scared so that I wouldn't be beaten again," the woman recalls.

After several days of abuse, Olha's contact lens burst, but the woman was not allowed to wash her face. There was not enough water, so it was used only for drinking. They were fed porridge once a day, sometimes not at all. When the woman started her menstrual cycle, blood ran down her legs. Olha spent 14 days in prison. The prerequisite for her release was the distribution of humanitarian aid allegedly from Russia. The volunteers were supposed to buy the packages and say that the Russian authorities had allegedly facilitated their work. Olha agreed although she had no intention of doing so.

Olha's apartment was searched: the cabinets were turned upside down, and her things were scattered. Russian soldiers took two phones, gold, and money. Olha was just saving for a car. In addition to physical damage, the volunteer suffered health problems. Her rib hurt, but she didn't know whether it was a crack or a fracture.

"I was afraid to go to a doctor because I didn't want anyone to see me. After the captivity, the military promised me trouble if I asked for help. In addition, I heard several stories from acquaintances. In particular, about a mother and her child who were taken to the hospital. Russians told her that in the morning the family would be taken to Crimea for treatment. They did not offer them their "help" but simply stated it as a fact. They ran away the same night," says Olha.

A massage therapist whom Olha knew personally remained in the city and helped to rehabilitate and get rid of the pain. She planned a visit to the doctor after the de-occupation of the city but returned to volunteering five days after the captivity. She says she was afraid for her safety but was more worried about the people who needed her. Moreover, she was forbidden to leave the city, so she decided to stay and be useful. Olha calls herself a small volunteer with a big heart.

Recently, a woman shared her story of being abused by the Russian military on social media. She has received many words of support and shares of the post, along with comments from Russians who firmly believe that their military has another purpose and is not abusing people. A few days later, Instagram removed the post for "hostile language or symbols" because it was against their policy. However, the woman continues to talk about it because she believes that such stories should be publicized. The world needs to know about it.