Preserves and defends Ukrainian culture. How Kharkiv Literary Museum works during full-scale invasion

The Kharkiv Literary Museum was opened in 1988 and still functions today. After February 24, 2022, it stopped its activities so that employees could evacuate exhibits. Later, the work was resumed in the formats possible at the time: first, online events, then exhibitions in different cities of Ukraine.

Despite the shelling, power outages and the lack of stable security, the museum tells about Ukrainian culture in its Kharkiv location.

"We cannot stop our activities and give a part of our life and work to someone trying to destroy us," says Tetiana Ihoshyna, Deputy Director for Development of the museum.

The interview with Tetiana Ihoshyna reveals how the museum functions during the full-scale invasion, the evacuation of collections, the importance of the museum for Kharkiv and the importance of preserving cultural heritage.

— What was February 24 like for the museum and its staff?

— On February 24, some of the staff came to the museum, where an exhibition with valuable exhibits was on display. It took them the whole day to remove the exhibition.

— Tell us about the museum collections and what happened to them during the full-scale war? How were the collections evacuated?

— We have original exhibits from collections dating back to the 1920s until the early 1990s. Those collections on display permanently and those in the storage fund are each valuable to the museum.

We have had experience in transporting them since 2014. The curators have developed special lists: the first and second stages [of exhibits – ed.] The most valuable first stage was collected before the full-scale invasion. This was an advantage because we did not spend time packing. However, this was only a part of the collection.

Due to the lack of specific evacuation mechanisms, we transported the first-stage collections in extreme conditions. We transported the second phase later, and it was already calmer, thanks to the experience of the previous one. Now everything is stored in relatively safe places.

— The first message on the museum's page at the start of the full-scale invasion read as follows: "Friends. The LitMuseum is closed for the period of martial law. The collection is protected! We will hold the planned events after the victory!". When did you decide to resume your activities, and how did it happen?

— It seems we didn't stop our activities for more than 2-3 weeks. The first thing we did was hold the traditional International Day of Poetry, which had always been held in the museum's garden, called "Reading on the Ladder".

We couldn't hold readings in the garden but didn't want to give up the event either. Having the quarantine experience of holding similar readings online, on March 21, 2022, we went out to the public after a pause spent evacuating the collection. The event took place online, where poets read their poems about the war, their experiences, and what conveyed the period's mood.

We cannot stop our activities and give a piece of our life and work to someone trying to destroy us.

The second significant event was the Night of Museums (an international event that allows you to see museum exhibitions at night – ed.), which took place in May 2022 in a hybrid format (offline or online). The event covered three cities — Lviv, Kyiv and Kharkiv.

In September 2022, events and activities started in Kharkiv. The Literary Kharkiv Festival, a joint project of the writer Serhii Zhadan and the museum, opened.

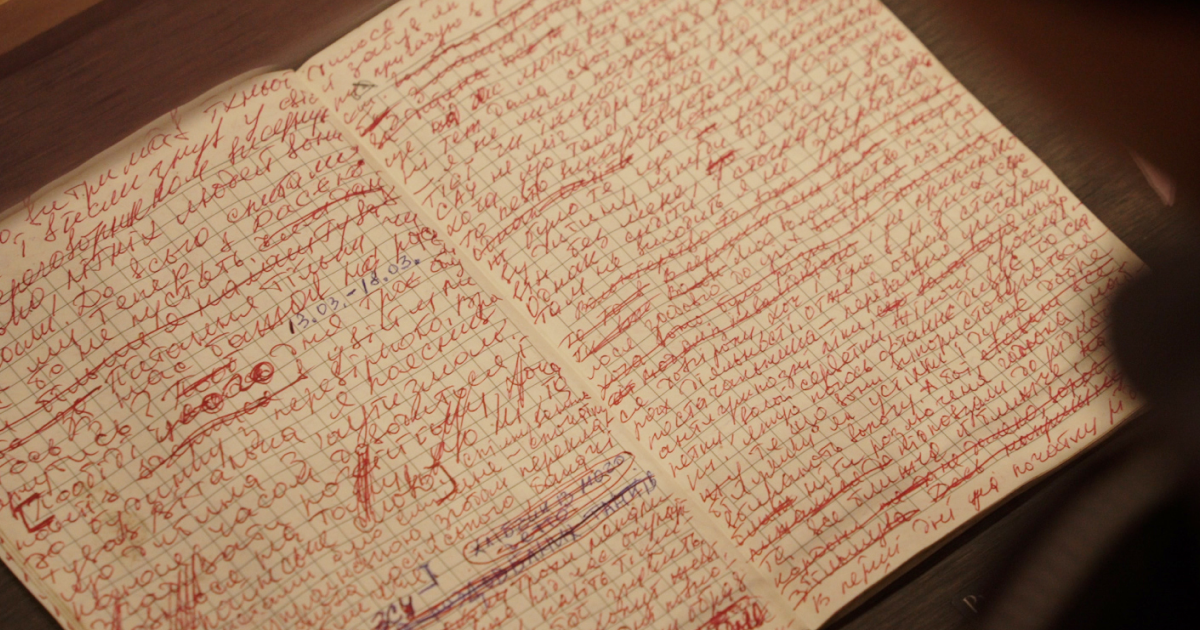

We returned to our building in March 2023. It was a day of offline poetry in a garden with a ladder and a new exhibition - the diary of writer Volodymyr Vakulenko (Russians killed the writer during the occupation of the Izium region, but he managed to hide his notes before he was kidnapped - ed.). We installed two exhibitions in May after the annual Night of Museums event. Today, the museum is open daily for visits to these exhibitions and events.

When we returned home, we used locations in different cities to continue our activities and promote our collection, Ukrainian culture, and literature in general.

War is not only about weapons but also a struggle between two cultures.

— What was the central message of these exhibitions? What did you want to convey?

— One exhibition shows why Kharkiv is an essential centre for developing Ukrainian culture, what it was in the 1920s and what it is today. The exhibition has its focal point, the Slovo House. Through this house, we talked about the importance of Kharkiv for Ukrainian culture.

We use the Slovo House and the LitMuseum for dialogue with Kharkiv residents and guests of the city. We need to tell why Kharkiv is a distinctively Ukrainian city, why it has survived and why it is made of concrete.

The idea for the second exhibition, Antitext, came up because the collections were evacuated.

We couldn't imagine being forced to hide our cultural heritage once banned by the Soviet government.

We realised we were forced to hide what we had already fought to discover. We thought the worst of times had already passed for this class of Ukrainian culture, and it should now be only on the surface, but it was packed away again.

We created this exhibition to maintain the dialogue with this cultural heritage and the opportunity to talk about the very meanings that cultural objects carry.

— What are you currently focusing on? Are there any topics that the museum addresses the most?

— We discuss Ukrainian culture, identity, and the right to independent development and life. It is about the fact that we are not part of something; we have our own separate culture. Today it is essential to talk about Kharkiv and Ukrainian culture in Ukraine and abroad.

The new season of the Fifth Kharkiv Literary Festival is called Ukraine and Europe. Through this project, we invite European intellectuals to Kharkiv for a conversation. These are writers, philosophers, and poets. They can tell us what they know about us, and we show them what we are. People abroad must understand what is happening in Ukraine, what kind of people are here and what we are fighting for.

Today, it is vital for us to be heard and seen. It is impossible to distinguish between cultural themes because we do not focus on a particular period, issue, or personality.

— The museum's first offline exhibition was dedicated to the writer Volodymyr Vakulenko. What were the difficulties of returning to such an offline format in Kharkiv?

— After a year of the full-scale invasion, we better understood the security system. This made it possible to realise that we could organise offline events in our home.

Several dozen people came to the event. We did not expect such a large number. Everyone was interested in the small exhibition with one diary of Volodymyr Vakulenko.

— After February 24, your collection was replenished with Volodymyr Vakulenko's diary. Do you plan to add anything in memory of Viktoriia Amelina, who died from Russian shelling in Kramatorsk on June 27?

— Victoriia Amelina is important to us not only because she handed over Volodymyr Vakulenko's diary. She was the first resident at the Slovo House when we decided to resume our activities there. She came to our first offline event, Reading on the Ladder, and was the first to read her poems.

The museum and Viktoriia had a warm and close relationship. She was essential to us and remains so. However, this tragedy is so fresh now that it is difficult to imagine the publication of Volodymyr Vakulenko's diary without Viktoriia Amelina. It is still difficult for us to talk about our further actions today.

— Has society's attitude to cultural monuments changed during the full-scale invasion?

— We have not conducted such surveys. The LitMuseum has been operating in Kharkiv since 1988. During this period, we have had different situations with Ukrainian culture; during this time, the museum has found its audience and expanded it.

If the LitMuseum was relevant, it found the strength to convey messages to society and create a cultural environment around itself. Therefore, during a certain aggravation period, the museum cannot stand aside, rely on better times, or stop its activities. We need to continue doing what we are doing.

— What is the significance of the museum for Kharkiv, and how does it affect its cultural identity?

— It is crucial for us that Kharkiv has a literary museum, a cultural institution that continues to talk about the cultural traditions of Kharkiv. We want to revive cultural traditions, rethink them, and offer new formats. We do not work for ourselves since visitors continue to come to us.

— Has the interest of foreigners in the museum increased, and in what way?

— The interest of foreign journalists has increased. There was a period when we communicated with them almost around the clock. It was essential to show them the state of development of Kharkiv's culture and what was happening in the city during the full-scale war.

They turned to the museum because it is Kharkiv's only working cultural institution.

— The Kharkiv LitMuseum has a virtual app to take an online tour of the exhibition space. What is the significance of this app for the preservation of Ukrainian culture? Can we use it to communicate with foreigners about Ukrainian culture?

— The app was developed and launched in October 2021. There are two virtual tours. One of them is about literature at school and how it is taught. It is about the writers included in school education and those not, and why some were added while others were removed.

The second exhibition is dedicated to the artist of the Kharkiv Literary Museum, Valerii Bondar, who worked at the museum in the 1990s. He was an active Ukrainian cultural figure. Thanks to his personality, a cultural all-Ukrainian environment was formed in the LitMuseum. We wanted to preserve his story as a part of the LitMuseum.

The online format increases the audience, and the English translation expands it. This allows us to reach a large number of people more easily.

— What projects do you plan to implement in the near future, and what can we expect from the Kharkiv Litmuseum?

— On July 29, we are opening a new exhibition in the Poetry Square - "Proper Names". We will raise the topic of literature and place names: why are the streets named after Russian writers who have nothing to do with Kharkiv or Ukrainian culture? What important names are not on our streets, and why is this bad? This is a question about how much space affects us.