Odesa through the full-scale war lense: Culture, mindset, decolonisation

I travelled to Odesa on July 22 to write a report on the cultural life of the city during the full-scale war. The day before, the museums in the city centre had already been damaged by Russian attacks. I walked around, took photos, collected materials, and in the evening, I took a train to Kyiv.

While I was sleeping on the train, the centre of Odesa suffered a massive attack. On Sunday, the city woke up looking different from what I had seen the day before, and several dozen buildings were added to the list of cultural monuments damaged by Russian shelling.

On July 18, the grain deal was terminated. Since then, Russians have been shelling southern Ukraine almost daily. The targets of Russian missiles and drones are not only port infrastructure and hangars but also historical monuments, residential buildings, and kindergartens.

In this report, read about the transformation of Odesa after the start of the full-scale war and the city's culture, which lives and develops despite the shelling.

Culture at gunpoint

I wake up around 6 a.m. and see messages from my colleagues and family asking if I'm okay. I immediately realise what has happened and sleepily look for the Odesa City Council's Telegram channel. "Many residential buildings were damaged as a result of nighttime enemy attacks...", "...the Transfiguration Cathedral was destroyed."

I stop at the video with the caption: "...Zhvanetskyi Boulevard was heavily damaged." Mayor Hennadii Trukhanov is walking past a building with a broken glass facade. I recognise the letters on the glass and the arrangement of paintings inside — the AURUM art centre.

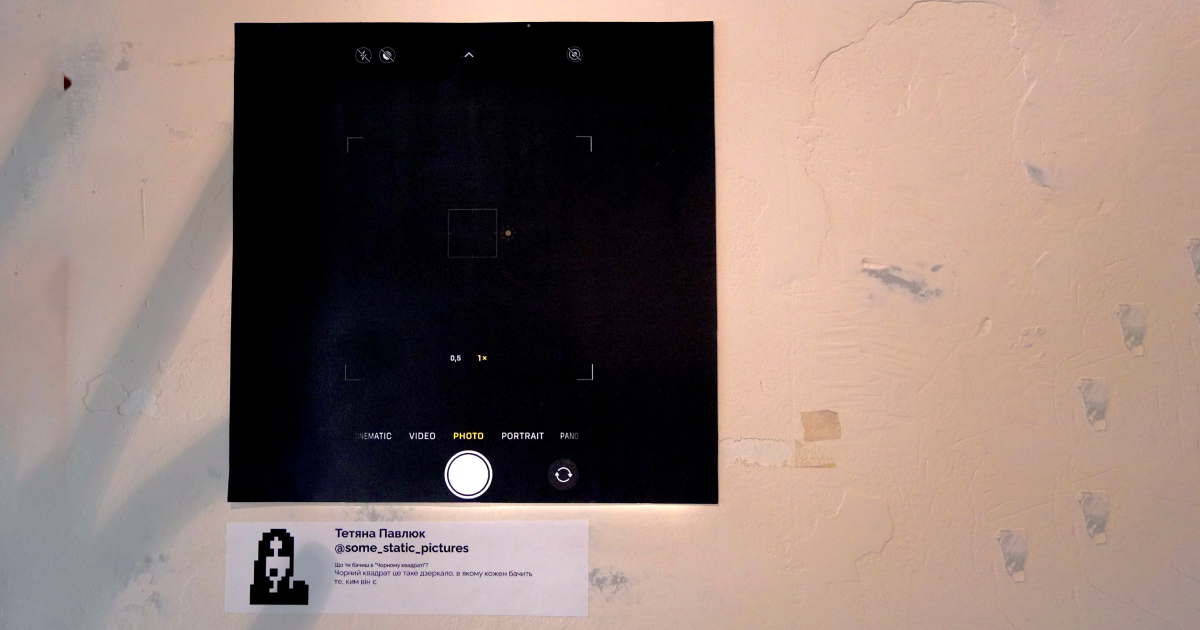

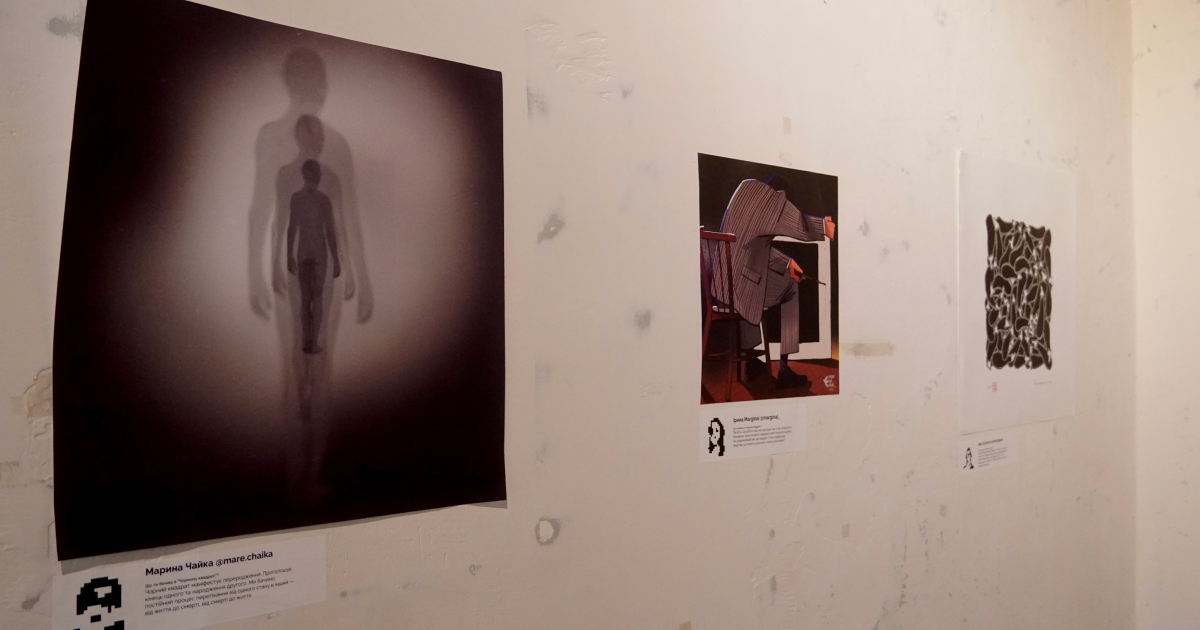

I managed to see the exhibition "Native Black" here. 14 artists interpret Kazimierz Malewicz's Black Square in their own way to make Ukrainian classical art more recognisable and interesting. The organisers call the exhibition the end of the era of occupation of Ukrainian art. They write that the first step to return the cultural heritage is to realise it is ours.

"The Black Square manifests rebirth. It proclaims the end of one thing and the birth of another, the flow from one state to another — from life to death, from death to life," reads a note under the image of Maryna Chaika, which remained behind the broken walls.

The July 23 shelling damaged 29 cultural heritage sites. Among them are those listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The historic city centre was granted this status on January 25, 2023. This attracts more tourists and puts the city authorities in charge of preserving the heritage and UNESCO in charge of protecting it.

If the hostilities cause damage to UNESCO sites, the first step is to determine the consequences and damage and the cost of restoring them to their original condition. The next step is to submit the collected materials to an international court, which will charge the perpetrator for the losses. These funds will be used to restore the area to its original state with all its elements and background buildings, as this is important for the historical integrity,

Volodymyr Meshcheriakov, Head of the Department for the Protection of Cultural Heritage Sites of the Odesa City Council, explained to Suspilne.

UNESCO condemned the missile attacks on Odesa. On July 29, the organisation's mission arrived in the city to assess the damage caused by the Russians.

On July 20, an earlier Russian attack also damaged Odesa's cultural monuments. Among them are four museums in the city centre — the Archaeological, Literary, Navy, and Western and Eastern Art Museums. The first one hasn't reopened yet — all the windows have been smashed. The Literary one is right next to it. After the attack, most of the windows were damaged, the interiors were damaged, and the ceiling collapsed in two halls. However, the museum is open, hosting exhibitions and lectures, as well as a sculpture garden.

Another museum that quickly recovered from the previous shelling is the Museum of Western and Eastern Art. An exhibition of paintings by Odesa-based artist Valerii Yukhymov is taking place in one of the halls. Two crimson canvases immediately catch the eye, contrasting with the crumbled plaster on the cracked pastel walls. On the left is "Dangerous Sea," and on the right is "The Arrival of the Barbarians." Between the damaged walls, there are windows covered with film. The curator of the exhibition says that they were quickly replaced so that the museum could reopen. She swept up the glass fragments herself.

In other halls, there is a large exhibition of posters donated to the museum by French artist and philanthropist Suzanne Savary. She often visited Odesa and brought gifts for the city's cultural institutions. In 1999, Savary was awarded the title of Honorary Citizen of Odesa.

"Why did she love Odesa so much? Did she have any relatives here?" I ask the curator of the exhibition.

"No, she had no family here. Can't one simply fall in love with our Odesa?" (smiles — ed.)

The cultural transformation of Odesa

When I came to Odesa this spring for the first time since the start of the full-scale war, I was surprised by the amount of blue and yellow. I had never seen such a flag density in any other city. With flags on buildings, banners, and posters, Odesa seems to be screaming that it is a Ukrainian city. It's as if it's saying: "Don't mind that the street is called Pushkinska. We are Ukrainians."

We talk about the changes in cultural life with Valerii Lavrovskyi, an Odesa native and journalist. He works for the local media outlet Maiak and writes about culture.

The paradox of Odesa is that the Ukrainian has not destroyed the Russian, as is the case in other cities, but has only added to the Russian that is already present,

Valerii states in his article for the SLUKH media outlet about the Ukrainianisation of his hometown.

"What do you mean by that? Even concerts by Russian artists are now banned," I ask him.

"Odesa, in my opinion, is in its own bubble: not everything Ukrainian reaches it, unlike Dnipro, Kharkiv, Lviv, or Kyiv. The organisers said that bringing Ukrainian artists was at least unprofitable. It's easier to take established Russians who have been selling out large venues. Now, some of their audience goes to see Monatik or Nastia Kamenskykh. In the Instagram stories of my friends, I can still see those damn MiyaGi & Andy Panda," (a Russian rap duo — ed.).

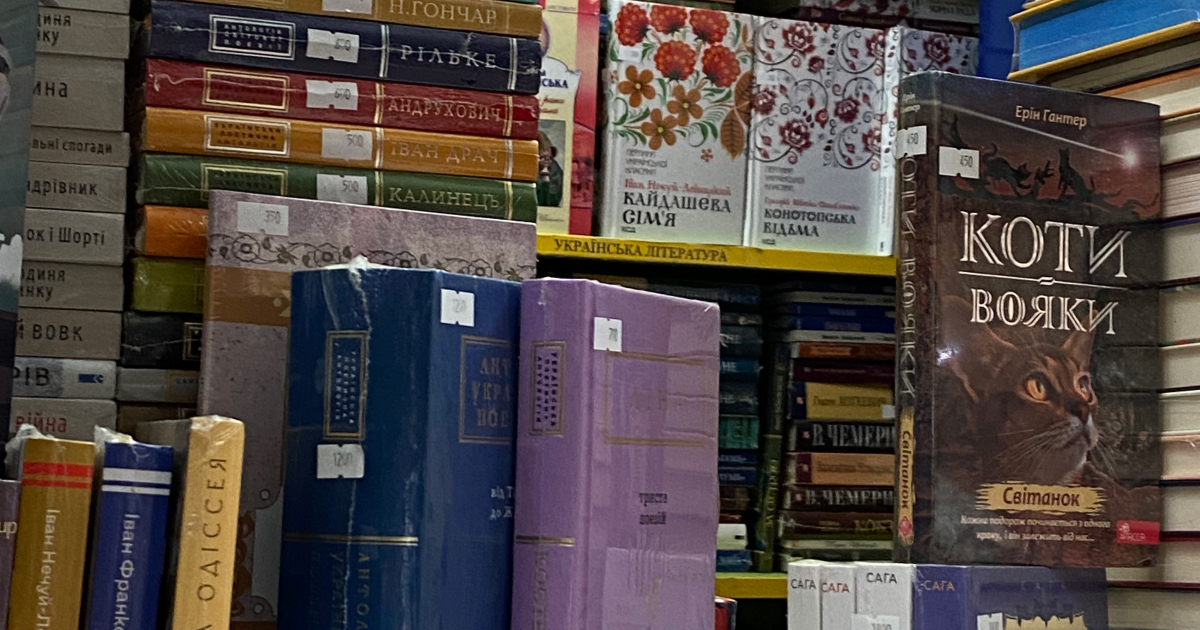

The book market was the place where I felt most that the presence of the Ukrainian product was added to the Russian one. The last time I was here was in January 2022, a month and a half before the start of the full-scale war. At the time, finding good Ukrainian literature among the dominance of Russian and Russian-language books seemed like a stroke of luck.

Most of the books in Ukrainian were legal texts. Now, the same shelves and shelves of Russian literature are full of books about Zelenskyy, the current war, and translations of the young adult genre. At one vendor, I found books from the Meridian Czernowitz publishing house and poetry collections from the A-Ba-Ba-Ha-La-Ma-Ha publishing house.

On one of the walls of the market is an exhibition of works by contemporary Ukrainian artists on the theme of war. It was organised by the Odesa Museum of Contemporary Art. Another much larger exhibition is on the main street of the city, Derybasivska. Opposite it, there are umbrellas with the Russian transliteration of the city's name "Odessa," and a representative of a travel agency is calling out to the city's guests in Ukrainian and Russian: "'Everyone is welcome to the tour. Criminal Odesa, Langeron, Odesa backyards... We are waiting for all of you. The departure is in five minutes."

Lavrovskyi complains about the small number of concert venues and organisers. Most often, new Ukrainian artists come to More Music Club. He says the Green Theatre used to be a great venue. It is now closed because there is no bomb shelter nearby that can accommodate a large number of people. At the same time, the city authorities allow the Bez Obmezhen concert to take place at the Spartak Stadium near Kulykove Pole, which also has no shelters.

I attended Palindrom's concert in Kyiv (a Ukrainian rapper — TN). There was a venue for 500 people, and it was sold out in two days. In Odesa, the hall was smaller and not even full, but it's a different crowd. People don't understand who he is, and even many of my friends don't know him. We have local events, like the stand-up club Vyrii, whose crowds are random: it can be a full venue or just three people. The guys campaign for Ukrainian-language humour and Ukrainian culture and hold educational events through the lens of humour,

the journalist says.

He also notes that there are no prominent local influencers in Odesa.

"There are no heroes or characters who would urge people to do something Ukrainian and then lead the crowd. The Odesa National Art Museum is popular all over Ukraine. The museum's chairman was Oleksandr Roitburd, a great guy, may he rest in peace (Roitburd died in 2021 — ed.). But he went to Kyiv, gained knowledge, returned to Odesa, and began to develop it. Local heroes are not created here,

Valerii says.

At the end of February, the collection of the Odesa National Art Museum was moved to one of the western regions of Ukraine, where it would be stored until the end of martial law. The museum is currently hosting an exhibition cycle called 'Languages of War.'

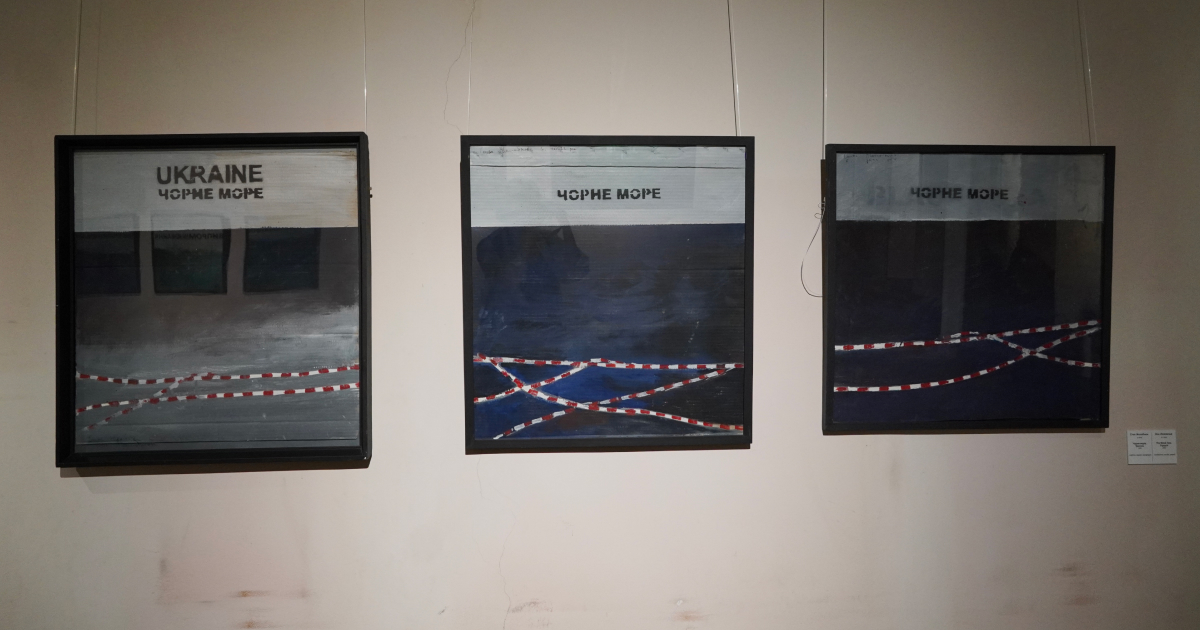

In the first hall, there is an exhibition by Stanislav Zhalobniuk called Black Sea. The artist reflects on the fact that the sea has turned from the personification of the salty wind, the sounds of the port, and calming waves into a source of new threats and the direction from which Russian missiles are flying.

On the second floor, in one of the halls, there is an exhibition by Yevhen Bal called Artefacty Nulia (Artefacts of the frontline — TN). In a red room, 15 objects related to the war are displayed on the walls. Number ten is a statuette of Aleksandr Pushkin, and in it are fragments of a high-explosive shell — "Suicide of Russian Culture." In the corner with the souvenirs at the exit from the museum, I notice postcards with the image of Pushkin.

"During this war, many Ukrainians of different ethnic origins realised their political national identity. In Odesa, particularly in cultural projects, there is a gradual separation from the imperial heritage, and a conversation about the difference between local historical and national consciousness is beginning. This is just the beginning of this journey, and the museum is also actively involved in it. We deliberately agreed to keep the dismantled monument to the so-called "founders of Odesa" in the museum's courtyard. We did this so that after the one-time act of dismantling, the museum could continue to discuss decolonisation practices through the use of the object," says Kyrylo Lipatov, Head of the Research Department of the Odesa National Art Museum.

"Can I see the monument to Catherine II?

"What do you want to see? It's just a woman lying there."

The woman lies in the courtyard near the main entrance to the museum, hidden in a metal box. You wouldn't notice it at first, but the museum staff show it to me and allow me to take a picture. It was dismantled on the night of December 29 after discussions and an online survey of the city residents.

Among the older generation, I often heard: "Why the hell did they have to demolish Catherine, she looked just fine there. And anyway, Trukhanov is a good manager." Among younger people: those who know the history are in favour of renaming, while those who do not know it are fine with it: "A decent monument, a decent mayor, he has stolen the least of all." Basically, this is how people voted in the elections in 2020,

says journalist Valerii Lavrovskyi.

Kyrylo Lipatov says that even though many museums have closed, the art museum, on the contrary, is working more actively.

"We try to maintain and even increase the number of exhibitions and change the focus. In peacetime, Roitburd and I used to organise 5-6 exhibitions a year and felt that we were overworked. Now, only six months have passed, and we already have 15 projects."

"Why has their number increased so much?"

"And why has the Ukrainian army grown? Why are so many Ukrainian businesses engaged in volunteering? Ukrainian art is mobilised, as is the whole society, and this is the only possible stance in such a war situation."