Maidan in the East: the history of resistance to occupation in Donetsk and Luhansk regions

Russian propaganda has divided Ukrainians into the pro-Russian east and the aggressive nationalist west for years. However, in 2013, the Euromaidan in the east began simultaneously with the one in Kyiv. In early March, rallies for European integration and against the arbitrariness of the authorities turned into a movement for the unity of Ukraine. The actions continued even after the so-called "referendums".

Please read the article about the events of that time from those who organised them.

It is necessary to understand the socioeconomic situation in the region to understand the context of the east at that time. The story goes back to the 90s when factories and plants passed into private hands for a pittance during the mass privatisation of state-owned enterprises. In exchange for loyalty, President Leonid Kuchma allowed regional elites to control industrial giants that formed local budgets and provided jobs.

"The level of salaries was determined not by the state but by Rinat Akhmetov, Valentyn Landyk, Yukhym Zviahilskyi, Kliuiev brothers and other oligarchs. They would tell residents that "Galician idlers" should be responsible for low wages" - this is how journalists Denys Kazantsev and Maryna Vorotyntseva describe the socioeconomic situation in the region in their book "How Ukraine lost Donbas". In 2011-2012, all large enterprises in the area were controlled either by Russians, pro-Russian or Donetsk oligarchs. Local authorities were under the control of those who controlled the economy.

During his presidency, Viktor Yanukovych tried to implement a multi-vector policy. Despite the signing of the Kharkiv Pact, which allowed the Russian Black Sea Fleet to be stationed in Crimea until 2042, Yanukovych continued to pursue European integration. The authorities argued that integration into the EU was an essential step. Still, on November 21, 2013, the Cabinet of Ministers issued a decree to suspend the process of preparing for the signing of the Association Agreement with the EU and "resume an active dialogue" with Russia and the Customs Union. Yanukovych had changed his course after his meeting with Putin. Such a sharp reversal outraged the society - people came out to the Maidan.

Donetsk: the beginning

In Donetsk, the first meeting took place at the same time as the events in the capital began to develop - on November 21, 2013.

"A little after 22:00, I saw the post of my friend Yevhen Nasadiuk, where he wrote that he was going to the Shevchenko monument. So I got ready and went there too. In addition to Yevhen, there were three other people. We stood there for a long time, talked, then took a photo and sang the anthem of Ukraine. After that, I recorded a video with Yevhen and left. The next day, about 300-400 Donetsk residents came to the monument because of the announcement on social networks," recalls journalist Kateryna Zhemchuzhnikova.

Euromaidan activists began to come to the rallies every day at 12:00 and 18:00.

"In the beginning, there were up to 30 of us; our goal was to be noticeable. We didn't think we could influence the situation. We came out to let all of Ukraine know that there was Euromaidan in Donetsk. Donetsk did not support joining Russia. There was Ukrainian society there," says Liubov Rakovytsia, head of the Donetsk Institute of Information.

Luhansk: the beginning

In Luhansk, the protests also began in late November. Executive Director of the Vostok SOS Foundation, Yulia Krasilnikova, recalls these events as follows:

"At first, the actions were organised by pro-European political forces every Sunday. But we [civic activists] felt we needed to do something like the Civic Sector of EuroMaidan in Kyiv to reach a wider audience. Those parties that came out at the beginning were quite marginalised in Luhansk, and apart from party activists, few people wanted to come out under their banners. So we gathered in small groups near the Shevchenko monument daily, played Ukrainian music and held thematic discussions. Then we started experimenting with different formats to make the actions more visible to citizens and the media. It all started with ten people. By the end, hundreds came out, and at the largest rally, there were thousands."

Volodymyr Semystiaha is the head of the Luhansk regional association of the "Prosvita" society, associate professor of the Department of History of Ukraine at Luhansk Taras Shevchenko National University and the head of the Ukrainian underground in Luhansk region in 2014. On November 30, he was in Kyiv. After that, he returned to Luhansk, but he often came to the capital to bring warm clothes and money to the Kyiv Maidan. Semystiaha says:

I even brought my son to the Maidan in Kyiv. He was studying in Luhansk school №17 at that time. After that, he was persecuted, and one of the teachers discredited the Maidan. When the son told the teacher he was lying, the man replied: "And you, 'Bandera', should be the first to hang on this battery,

A wave of rallies also swept through the cities of the regions. There were actions in Mariupol, Pokrovsk, Kostiantynivka, Kramatorsk, Sloviansk and Rubizhne.

Anti-Maidan

On December 4, in response to the mass opposition rally in Kyiv, the Partiia Rehioniv (Party of Regions) in Donetsk organised a rally supporting the President's course. As a result, several thousand people were brought to the Donetsk Regional State Administration building by bus. They had flags of the Party of Regions, banners with slogans "Donbas for stability", "Donbas supports the president", "Thousands rally - millions work", "New Maidan - new deception", and the like.

"The mass crowd consisted mainly of workers of state mines. Thus, the rally was financed by the local budget. The Party of Regions once again tried to convince Donbas that the residents of other regions of Ukraine want to deceive it and live at its expense," the book "How Ukraine lost Donbas" says.

Dictatorial laws and their consequences

On January 16, 2014, the Verkhovna Rada adopted a package of so-called "dictatorial laws" restricting the rights of citizens by a show of hands. The next day Viktor Yanukovych signed them. On January 19, confrontations began on Hrushevskyi Street in Kyiv. In Donetsk, protesters planned a trip to Yanukovych's estate.

"The party "UDAR" headed by Yegor Firsov, organised the trip. We did not support the idea because we understood that it could "annoy" opponents. Actually, January 19 was the turning point when "titushky" [mercenaries who participated in pro-government movements and attacked protesters during the administration of Viktor Yanukovych - ed.’s note] first gathered and beat activists. After that, they pushed us out of the square where we usually gathered," says Liubov Rakovytsia.

After January 19, almost every protest in Donetsk was disrupted. Zhemchuzhnikova recalls that in addition to constant moral and informational pressure, activists were hunted by "titushky" from Horlivka sports clubs. Then the first physical clashes began with catching and beating activists alone in the yards, surveillance and threats. Since January 26, 2014, people could not participate in the rallies because of constant provocations, physical confrontation, moral pressure, and posting leaflets about activists.

In Luhansk, the pressure on activists intensified along with the unfolding events in Kyiv and Donetsk. Krasilnikova says that the first attacks on activists were in December, "titushky" hunted them down on the way home from the rally. Then, at the rally itself, when they tried to watch a film about Mezhyhiria, they tried to pour brilliant green antiseptics on the equipment and people. Then, severe persecution began in February. Krasilnikova said.

When mass beatings and murders took place on Maidan in Kyiv, the so-called Luhansk Guard approached us with sticks and threats that if Kyiv Maidan did not disperse, they would come to kill us because we allegedly supported the killings of Berkut

On February 23, activists held a rally requiem for the Heavenly Hundred, which was the last for Euromaidan in Donetsk.

The rally lasted for 20 minutes and was possible only because the then police surrounded the monument to protect the activists.

"There were maybe a hundred of us; outside the police cordon, there were about a thousand aggressive pro-Russian people who came with bats, metal and wooden sticks with nails hammered into them. It was the last day when Donetsk police did their duty because they would start playing along with the pro-Russian crowd," says Zhemchuzhnykova.

Donbas is Ukraine

On the night of February 22, Viktor Yanukovych fled Kyiv. On the same day, the Verkhovna Rada supported the resolution on the President's self-removal and the appointment of early elections. As a result, Oleksandr Turchynov was elected Chairman of the Parliament and became the acting President of Ukraine.

On March 1, the first large-scale pro-Russian rallies took place in Luhansk and Donetsk, marking the beginning of the "Russian Spring". According to eyewitnesses, many participants were unfamiliar with the area and spoke with Russian accents.

On March 2, Luhansk regional council declared the new Ukrainian government illegitimate. Yulia Krasilnikova says:

The position of the administration was clear. We did not expect them to act appropriately. We were disappointed that the events were ignored at the state level. People with machine guns were running around the city. It affected the public mood - there was a feeling of despair and that they threw the region under the bus

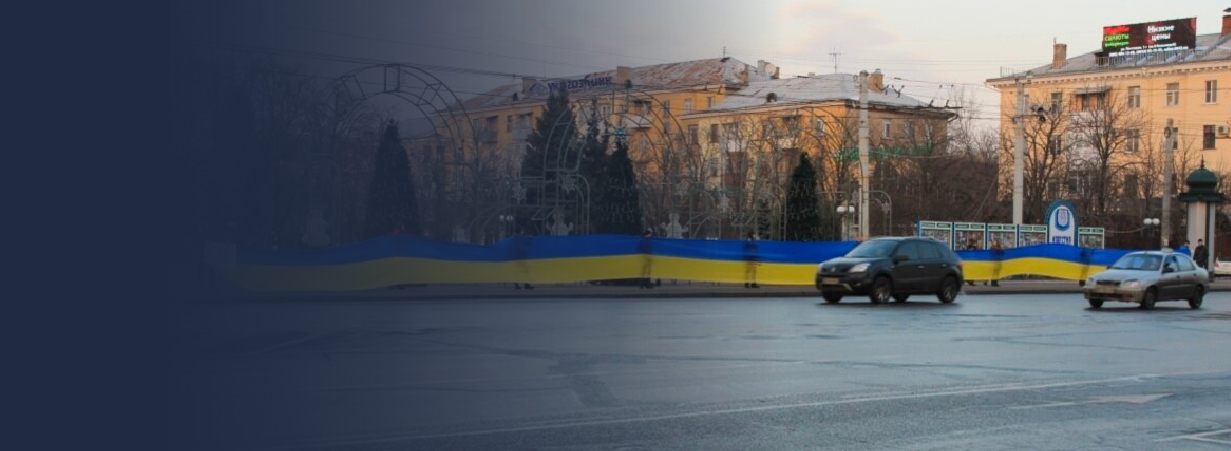

On March 5, supporters of Ukraine held a rally in Donetsk. This date was Donbas's Day of Civil Resistance to the Russian Occupation. Several thousand people gathered in Lenin Square under yellow and blue flags to speak out against the country's split.

"The protests "Donetsk is Ukraine" started in early March in contrast to the fact that on March 1, we saw 10 thousand people involved in "Russian spring". Some of them were assembled in a traditional way for the Party of Regions - pressure and coercion against state employees, as well as bringing marginal participants from depressed settlements of the region for money. But the active part was from Russia. "Donetsk is Ukraine" rallies were an attempt of Donetsk residents to show that the pro-Russian public was not the real voice of the city," explains Zhemchuzhnykova.

Krasilnikova says that mass actions in March were also due to the beginning of the occupation of Crimea. Many people who supported pro-Ukrainian rallies, but did not participate, came out because it was apparent that war had started in the country.

"Although the pro-Ukrainian rally was less formidable and loud than the separatist actions, it was impossible to ignore it. And the effect of it would have been much greater if the local authorities at least morally and verbally supported the pro-Ukrainian actions. But Donetsk authorities ignored it", - Denys Kazantsev describes the rally in his book.

On March 9, in Luhansk, a peaceful rally dedicated to the birthday of Taras Shevchenko was attacked by anti-Maidan activists.

Volodymyr Semystiaha and Iryna Verihina, deputy head of Luhansk regional administration and head of the Luhansk regional organisation of the political party Batkivshchyna, agreed on an action plan. The meeting was opened by "educators" from school №59 - girls played the bandura and sang. At the same time, the regional council organised an action across the street. There came people from Rostov, Belgorod, and Voronezh regions.

"March 9, 2014. Luhansk. I would call this day the beginning of the occupation of Donbas. A peaceful photo, and in a minute, when the song is not over, a crowd of pro-Russian mercenaries with sticks and bats will begin to disperse people who came to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the birth of Kobzar. On this day, the Russian flag was to appear over the building of the Luhansk Regional State Administration for the first time. The next day, control over the RSA was restored, but the aggression broke out on that day," wrote Iryna Verihina.

The first murder in Donetsk

On March 13, a bloody clash between supporters of Ukraine and Russia took place in Donetsk. It ended with the beating of Ukrainian activists and the murder of Dmytro Cherniavskyi, a member of the Svoboda Party. He was 22 years old.

Kateryna Zhemchuzhnikova says that when the first death occurred, the police parted to let an angry crowd with homemade weapons kill pro-Ukrainian protesters.

"The massacre occurred on Lenin Square and was the first such incident in the city's recent history. On that day, armed militants with knives, bats and rebar appeared in Donetsk for the first time and began to beat and maim supporters of Ukraine, trying to inflict the most severe injuries," reads the article "How Ukraine lost Donbas".

The beginning of the war

After March 13, a wave of seizures of administrative buildings swept across the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. On April 12, 2014, a group of Russian saboteurs led by Igar Girkin (Strelkov) entered Sloviansk. On April 28, protesters in Donetsk tried to march down the city's main street. Zhemchuzhnykova says that the protest did not occur because it was dispersed by "titushky", to whom the Donetsk police gave their ammunition.

"When public actions became impossible, the "Interreligious Prayer Marathon" - a daily event where believers of different faiths gathered to pray for peace - began its activities. The only ones who did not join were representatives of the Moscow Patriarchate. These daily joint prayers were held even during the occupation, particularly when Girkin's militants entered Donetsk. The priests were periodically abducted and tortured, but they continued. Finally, in early September, the prayer site was destroyed, and then those who remained in Donetsk were forced to move to an underground format of meetings," says Zhemchuzhnykova.

Volodymyr Semystyaga was the head of the Ukrainian underground in the Luhansk region. Participants posted leaflets with epigraphs of Shevchenko's words "Love your Ukraine, love it in time of trouble. In the last difficult moment pray to God for her" and Volodymyr Sosyura's poem "Love Ukraine". Then there was a text that ended with the words "death to Putin and his Luhansk henchmen". In addition, they put up armed resistance: destroyed three cars and a machine gun nest on the territory of the brewery, tore down tripwires on the territory of the Luhansk regional state administration and fired at the administration itself.

The last peaceful event held by "Prosvita" students was on May 22, 2014, at the Ukrainian Canadian Renaissance Center, dedicated to the day of Shevchenko's reburial.

On June 23, Semystiahja was arrested, but then the militants did not know about the existence of the underground: "When we found the protocol on the formation of the underground movement, we were shocked. They showed me leaflets, but they could not guess to compare the handwriting to establish my involvement. If they had, the consequences for me could have been terrible. After two months in captivity, I managed to escape."

The symbol of Ukrainian actions in Luhansk was a 40-meter Ukrainian flag, unfurled along Sovetska Street. On March 9, during an attack on activists, the first line of people holding the flag was "torn down" by pro-Russian "titushky". They tore the flag, and when people ran away in confusion, they lost it.

Yulia Krasilnikova says: "The next day, I received a call from a policeman who was supportive of us and told me to come to the police station."

He brought me a part of this flag in a bag. This flag is still in Luhansk. It is safely hidden and waiting for the opportunity to be unfurled again