Kharkiv in the reach area. How the city lives under constant Russian attacks

You immediately notice a strong contrast as you arrive in Kharkiv on the Intercity train from central Ukraine. In central Ukraine, spring trees are in bloom, and birds are singing, while in Kharkiv, spring begins with a blackout due to constant Russian shelling.

In March, the Russians destroyed the Zmiivska thermal power plant in the Kharkiv region with a missile attack. It supplied electricity not only to Kharkiv but also to the whole region, part of the neighbouring Sumy region, and parts of the Luhansk and Poltava regions. Massive attacks on energy infrastructure across the country followed this.

The Russians regularly shell Kharkiv with missiles, attack drones, and guided bombs. In May, they launched an offensive in the north of the region. But people still study, work and open new businesses in Kharkiv.

Read the full story about a day in the life of Kharkiv's residents, their moods in the face of power cuts, constant Russian attacks and information and psychological operations.

"Kharkiv is a city of social advertising and broken windows" - how citizens live despite shelling and power cuts

The morning in Kharkiv begins with the sound of generators and traffic lights. The traffic lights are not working because of the power cuts.

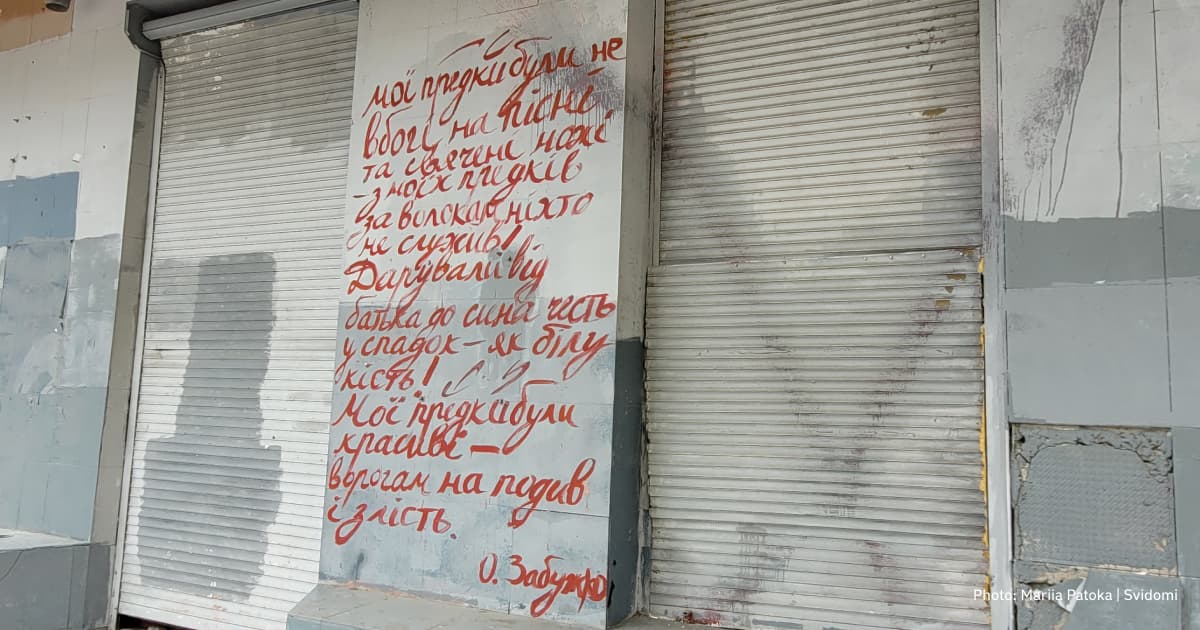

Almost as soon as you arrive, you see plywood instead of windows. It seems that there is not a single house in the city with a whole window. There is a lot of social advertising on the streets — on billboards, stalls, posters hanging from plywood instead of windows. Most of the posters say, "Ukraine will win", "Kharkiv is a heroic city", and "Kharkiv lives and works".

"Kharkiv is a city of social advertising and broken windows," says my first interviewee, Yuliia Napolska, a volunteer, producer of the media outlet Nakypilo, and a resident of Kharkiv.

We go to the Franyk coffee shop on Freedom Square, which was damaged by shelling in December 2023 but recovered and reopened in March 2024. There, Yuliia talks about how she organises her daily life, depending on the power cuts and despite the Russian shelling.

"You already have established routes. The office is prepared for blackouts. Not only journalists work there, but also our friends, there is always a telephone connection, light and you can wash. People are stocking up on things they need in case of a blackout - water, burners, gas stoves for tourists," she says.

The people of Kharkiv are prepared for power cuts. Shops, cafes, and banks have generators, and people have power banks and various charging stations, Yuliia says. "People use power cuts as an opportunity to go for a walk in the park. They just go out into the blackout and hear a beautiful spring day. Birds are singing, generators are working, and people are walking.

The shelling is a much bigger problem for residents than the blackout. "The Russians are using everything against Kharkiv — rockets, bombs, checkers," says my interlocutor. The main problem with guided bombs is that they are almost impossible to shoot down. Air Force spokesman Yurii Ihnat says the best method is to destroy the bomb carriers, namely Russian fighter jets.

"After the first news about these KABs, I got scared. I set a red line for myself. Of course, the blast wave is stronger and shatters more glass, but I can't say that anything has changed compared to the S-300,"

says Yuliia when I ask about the launch of guided bombs against the city.

Despite this, according to the city council's response to Svidomi's request, Kharkiv is home to over a million people. More than 197,000 are internally displaced. In March, evacuations were announced from the border areas of the region, which are also suffering from artillery and mortar attacks.

I ask Yuliia if she plans to leave Kharkiv. Pointing out the window of a coffee shop in the mothballed building of the regional state administration, she tells me that she was there at the time of the attack in March 2022.

"If Russian planes fly over Kharkiv, I will probably leave. I didn't have a car in 2022, but now I do. I will get in the car and drive," Yuliia concludes.

"We all decide to stay here". How Kharkiv is responding to Russian information attacks about the "seizure" of the city.

As we walk with Yuliia down Sumska Street to Shevchenko Park, I notice the military. There are many of them in the city. Yuliia says that the military has become an integral part of Kharkiv society. "They used to be students — now they are soldiers."

The office of the Nakypilo media group is quiet, and there is no sound of cars. The lights are dimmed, and the windows are slightly open. It's a basement, so it's cool and gives a sense of protection.

The media centre is prepared for blackouts, so much so that they even rely on journalists from other media outlets to work there, especially if the connection is lost.

In addition to rocket and bomb attacks, Russia is also spreading information attacks about the 'capture' of Kharkiv. They coincide with the density of the shelling, which is confirmed in conversations with Kharkiv residents.

"It makes me angry. It makes me very angry. The fact that the Russians are writing about how they are 'razing Kharkiv to the ground', the Russian media are writing about Kharkiv as a 'used up city'. This only causes irritation and a lot of pain for your city," says one of Nakypilo's media workers.

If you walk around Kharkiv, you will notice how clean the city is. This attitude toward cleanliness is impressive considering the frequent shelling, destruction, and shattered glass. In Shevchenko Park, the benches are freshly painted, and the flower beds are newly planted and well-maintained.

According to the Nakypilo media, the city authorities have become as open as possible during the war.

"To meet the mayor, all you have to do is come to the shelling site at night," says the media producer.

However, not everything the city authorities do is welcomed by the locals. Some issues even provoke a mixed reaction.

"Kharkiv is made of reinforced concrete" is a slogan almost everyone in Ukraine has heard. At first, it went viral on the internet, and volunteers and a Kharkiv artist coined it. But then it was picked up by the city hall's communications team, and now posters with the slogan hang around the city and greet newcomers at the train station.

Some people find the slogan "uplifting", and if it does not harm, then why not? Others, however, are already annoyed because "Kharkiv is people" and "this reinforced concrete is being destroyed every day by Russian rockets and shells".

"The fact that Kharkiv is standing is the strength of many people. It is the strength of the military holding the frontline, the strength of the volunteers who are helping, and the strength of activists, journalists, utility workers and energy specialists. That's the only reason we can say that Kharkiv is made of reinforced concrete,"

says Nakypilo producer Lina.

I ask the people I meet why they choose to stay in Kharkiv despite the Russian shelling and power cuts.

"Kharkiv residents see what is happening. And we all make a decision, which was either made once or is made every day, every minute, to stay here. And this choice should be respected," Lina concludes.

"Kharkiv is a big printing house". How power cuts and shelling are affecting the local publishing industry and the rest of Ukraine

Kharkiv is the second-largest city in Ukraine in terms of population. Its importance to the country's economy cannot be underestimated, even in a simple example — book publishing. More than 80% of Ukrainian books were printed in Kharkiv before the full-scale invasion. It is home to the country's largest printing houses, such as Unisoft and Globus. Russia is also attacking them. In March, the Russians destroyed two printing houses, Gurov & Company and Aurora, in a rocket attack.

The almost constant power cuts in the city have affected the work of the printers. The delay in printing is affecting book publishing in the country. The realities of the market now include postponement of deliveries, price increases and loss of copies due to Russian shelling.

Oleksandr Savchuk, the head of the publishing house, says in his bookstore Book Shelteroom that there are already delays in the printing and delivery of books.

"Printers have been busy before. Some of them gave a month's notice. Now it's one and a half or two months. Even quite large printers do not have enough capacity and generators to start the process. But the main thing is that we can work and are in Ukraine,"

he says.

As the bombing intensified, there were calls on social media for support for businesses in Kharkiv. Savchuk's publishing house felt the impact, which was reflected in orders from printers. Some of the publishing house's titles were dismantled and reprinted.

Oleksandr says that the publishing houses switched to remote work during the pandemic, but the editors and proofreaders worked in the same city. Now the situation is different, and publishing house employees can be employed in other cities and countries.

The Book Shelteroom is a small room in the basement. On the bookshelf are copies of the publisher's books, a record player and a few old armchairs. The publisher holds meetings and presentations here for a few people. So, I ask Oleksandr how diverse the audience for his events is and how interested the people of Kharkiv are in the themes of the publisher's books.

"At first, our story (of the publishing house — ed.) resonated in Kyiv and Lviv. It was the 2010s, and there I saw how it could work. There are readers who are really interested. They criticise, suggest, and thank us,"

Oleksandr says, adding that the calculation that Kharkiv is a large and student city did not work at first.

"It was only in 2022, around the summer when the printing houses reopened, that we felt this demand from Kharkiv," he says.

Kharkiv residents became interested in Ukrainian culture, and cultural and media institutions responded. The Literature Museum opened a residence named after Yurii Shevelov, and local media such as Nakypilo Radio, Suspilne and Luke Media developed their cultural and educational projects and became more and more visible among the city's residents. The publishing house became part of the city's cultural blossom.

"Do we even need a place like this? You can just send a book online or come to the warehouse and pick it up. It turns out that we do. Since 2022, people have been buying books on the history of Ukraine, on the destruction of cultural monuments, and on ethnography to make sure they understand everything correctly. That we have such a history of relations with Russia, that there really were so many people killed there, that there really was a destruction of a cultural monument of architecture and art," Savchuk says of his visitors.

You can see it in the streets of the city. Especially because of the Ukrainian language — it absolutely dominates the public space. Advertising banners, signs, billboards, and even drawings and murals are in Ukrainian. Kharkiv, which was the centre of Ukrainisation (policy or practice of increasing the usage and facilitating the development of the Ukrainian language and promoting other elements of Ukrainian culture – ed.) in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, is still there in the twenty-first.

Oleksandr believes that for Kharkiv residents, the choice of language is a choice of position.

"I am trying to set up a Ukrainian language course where people can come, ask questions and just listen. There are a lot of people who want to speak Ukrainian, at least in public, but they don't know how. Why don't people speak in public in Kharkiv? I think they are shy because they don't know the language. They can't finish a sentence in Ukrainian," he says.

The Ukrainian character of Kharkiv can be traced even in a single book — The History of Sloboda Ukraine. It was written in 1918 by the rector of the Imperial Kharkiv University (now Karazin National University — ed.), Dmytro Bahalii, in which he explored the formation and development of the region of Sloboda Ukraine. It was republished in 1990 by the Osnova Publishing House and in 1993 by the Kharkiv-based Delta Publishing House.

Oleksandr Savchuk says the book had a great influence on him.

"The 13th chapter is called 'Kharkiv as a Ukrainian city', and I remember what caught my attention. I started to read what it was about," he says, showing me the book, which is already in the 2019 edition of his publishing house.

I asked Oleksandr what I asked all my interviewees — why he stays in the city, under constant shelling and now power cuts, and how it affects his condition.

With a smile, he replies that the stress is so deep that it has probably become a background noise.

"Most people in Kharkiv know why they are here. As far as the war is concerned, this is of no use. It only gives the enemy information that people are not leaving, which means they want to live in Kharkiv. They are morally stable. So why should I leave? Personally, I am at home, and I think it is the same for most people. I am kept by my work, by the fact that I am doing something that I think is necessary,"

Oleksandr concludes.

We say goodbye, and I walk down the sun-drenched Poltavskyi Shliakh street, where the scars of the Russian attacks are less visible. Here, Kharkiv looks like it did before the full-scale war broke out: cars go in all directions, people come home from work, and windows are intact. Only the noise of generators and street signs remind us of what really happened.

"It's easier in Kharkiv because you can see what's really going on." How the mood in the city has changed since the start of the Russian offensive in May.

On the morning of May 10, the Russians launched an offensive in the northern part of the Kharkiv region. The Economist outlet published the Russians' plans. They were going to get within artillery range of Kharkiv, shell the city and hold back some Ukrainian troops in the direction of Kharkiv. Now, Ukrainian forces have stopped the offensive near Vovchansk, five kilometres from the Russian border.

Olena Leptuha, editor-in-chief of Radio Nakypilo, says the situation has become more tense. I talked to her on May 20, when a day of mourning was declared in Kharkiv. On May 19, the Russians shelled Cherkaska Lozova. Six people were killed, including a pregnant woman.

"There is more fear now. I see in my house that there are more empty flats. People have decided to leave the city to wait it out," she says, describing the change in mood among residents.

People from the border area, from Vovchansk and Lyptsi, are being evacuated to Kharkiv. They are partly replacing those who are leaving the city.

"We have a lot of internal migrants from the region, from the neighbouring Luhansk and Donetsk regions. So, there are a lot of people in the city. There are traffic jams and congestion on the roads. People are still sitting in cafes and walking in the streets," says Olena.

I ask her about the mood of the city's inhabitants. Russia is spreading propaganda and manipulation about 'taking the city' and 'turning Kharkiv into a grey zone' like a snowball. Olena says the shelling is a bigger problem for Kharkiv residents.

"After May 10, they started shelling in a very chaotic way. Air raid alerts can now last for 18 hours. The Russians can shell at night one day and early in the morning the next. They also use double-tap tactics — hitting the same place when there are medics, rescuers and journalists. This has a greater impact on the psychological state than the PSYOP," she says of the mood in the city.

But Olena says the regional authorities could have been better prepared to evacuate people from Vovchansk, Lyptsi and other border villages.

"You saw the footage from Vovchansk. People were just running away from the KAB. It's hard to see and experience. We could have been better prepared. The attack is on the same settlements that were occupied in 2022. The locals who returned thought it would never happen to them again," she concludes.

I ask her if she has noticed any changes in Kharkiv's businesses. Olena says that the Russian attack in May has not affected her work much. The war, in general, is having a much bigger impact.

"Small businesses, like cafes and shops, are working. The big factories that were destroyed in 2022 have certainly not recovered. Some industries are operating in basements if they can. Farmers are working. They have cleared the fields of mines and have been able to sow more land,"

she says.

Olena also notes that printing houses are working and printing newspapers despite the power cut.

"In border communities like Zolochiv, there is no internet connection because the towers have been destroyed. That's why the Zoria newspaper is delivered there, to keep the inhabitants informed. This is an element of information resistance," Olena smiles.

I ask her why she stays in the city despite the intense bombardment and whether she is considering leaving. Olena replies that she will leave if her house is threatened by shelling.

"We believe that Kharkiv will not be occupied. There is a lot of work to do here. Our office is prepared for power cuts, but I hope we won't have to spend the night here. We already have a well-developed algorithm. In 2022, part of the team would be in Kharkiv and part outside. And they could cover for each other in case of blackouts,"

she says.

She adds: "I was in Lviv for the Lviv Media Forum. And I want to tell you that it's easier to be in Kharkiv, to live there. Here, you see what's really happening in the country, and you don't panic," Olena concludes.

Before we say goodbye, Olena asks me to remind others outside Kharkiv that the phrase "The situation is difficult but under control" is tiring, but it illustrates the state of the city at the moment. Despite the shelling and Russian information operations, the people of Kharkiv continue to study, work, volunteer for the army and simply live here.