From being neglected to becoming a weapon: how Ukrainians' attitudes towards the Ukrainian language have changed

The Ukrainian language has been suppressed and banned for 400 years. Russia was the main culprit.

After regaining independence in 1991, Ukraine was given the opportunity to protect and develop the Ukrainian language without imperial decisions and influence. However, expectations were not fully met. For a long time, the Ukrainian authorities did not deal with the language issue and the promotion of the Ukrainian language. At the same time, Russia tried to keep Ukrainian society in its sphere of influence by spreading the Russian language.

The article describes the changing attitudes towards the Ukrainian language.

This article was published as part of the special project 'The War Continues: A History of Ten Years of Resistance'.

Ukrainian language policy in independent Ukraine

In 1996, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine adopted a constitution. According to Article 10, Ukrainian became the state language of Ukraine. In the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Ukrainian was also considered the state language. However, the law of the Ukrainian SSR allowed the use of national languages of other Soviet republics at work, in party organisations, and in “places of residence of the majority of citizens of other nationalities”.

The Russian Empire and the Soviet Union took different approaches to restricting the Ukrainian language. In the Russian Empire, Ukrainian was banned outright — by Peter the Great's decree of 1720, which prohibited the printing of books in Ukrainian; the Valuev Circular of 1863, which banned the printing of educational and religious books in the "Little Russian dialect"; and the Ems Decree of 1876, which prohibited the teaching of Ukrainian in schools, the organisation of concerts or theatre performances, and the import of books printed in Ukrainian.

In the USSR, Russian became a privileged language. It was the language of scientific dissertations, which, according to a 1970 decree, had to be defended only in Russian. It was the language of education, especially after a 1978 resolution of the USSR Council of Ministers, according to which Russian was to be taught in "the first grades of secondary schools with Ukrainian as the language of instruction" in rural schools, technical schools, etc. In 1984, teachers of Russian received a 15% salary increase compared to teachers of national languages.

The Law on Languages in the Ukrainian SSR came into force in 1989 and remained in force in Ukraine until 2012. According to the law, Ukraine had to ensure "the free use of Russian as a language of inter-ethnic communication", and civil servants had to be "proficient in Ukrainian and Russian and, if necessary, in another national language".

After the restoration of independence, the Ukrainian government adopted laws to promote and protect the Ukrainian language, although no specific language policy was implemented. For example, in 2006, the government issued a decree on the mandatory dubbing and subtitling foreign films into Ukrainian for distribution and home viewing. From January 2007, half of the films had to be dubbed into Ukrainian, and from July 2007, 70%.

Ukrainian distribution companies supported this decision. Companies such as "B&H Film Distribution" and "Kinomania" personally signed contracts with film production studios for distribution on the Ukrainian film market, and the studios prepared the rental copy and paid for dubbing.

“After the introduction of mandatory dubbing and subtitling, B&H increased its share of box office receipts from 30% to 45%,” said Tetiana Smirnova, executive director of Film Forum Ukraine.

Russian distributors working in the Ukrainian market reacted negatively to the resolution. According to the then-head of the State Cinematography Service, Hanna Chmyl, Russian distributors brought films from production studios to Ukraine with Russian dubbing. Their market share was already only 30% at the time of the resolution, and they could not increase it because of the resolution.

The then Vice Prime Minister Dmytro Tabachnyk also criticised the resolution (in 2023, the Security Service of Ukraine announced his suspicion of collaboration with the aggressor state — ed.) He considered dubbing films into Ukrainian to be an "economic burden" for Ukrainian distributors.

In December 2007, the Constitutional Court of Ukraine upheld the resolution as constitutional. The Department of Information and Press of the Russian MFA criticised the Constitutional Court's decision, citing the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (Ukraine ratified the Charter in 2003 — ed). According to the Russian ministry, Ukraine should have promoted the distribution of films in minority languages, which would have been in line with the charter. The country that has adopted the Charter should promote the use of minority languages in cultural events, but the Charter does not say anything about dubbing foreign films.

In 2012, the Verkhovna Rada adopted a new law, "On the Principles of State Language Policy", or the Kolesnychenko-Kivalov law (after the names of the two authors of the law: Vadym Kolesnychenko and Serhii Kivalov of the Party of Regions, which is banned in Ukraine — ed.) The law expanded the use of regional languages if the number of speakers of these languages is at least ten per cent of the population of a particular region.

The law was applied to 18 languages, including Russian, Belarusian and Crimean Tatar. Article 7 of the law obliged local authorities, businesses, educational institutions and citizens where a regional language is spoken to protect and develop regional languages.

Ukrainian society protested against the law. Opposition MPs from Arsenii Yatseniuk's "Fraktsia Zmin", Vitalii Klitschko's "UDAR" and Oleh Tiahnybok's "Svoboda" parties took part in a rally against the law. Rallies against the law were held in many cities of Ukraine — Kyiv, Lviv, Zhytomyr, Poltava, Kherson, Chernihiv, etc.

The Ukrainian World Coordinating Council condemned the adoption of the law, calling it "an attempt to cynically abuse the fundamental national value preserved by generations of Ukrainians at home and abroad — the Ukrainian language".

Mustafa Jemilev, Chairman of the Mejlis from 1991-2013 (the representative body of the Crimean Tatar people — ed.) and Member of the Parliament of Ukraine from 1998-2019, also spoke out against the adoption of the law.

"The Crimean Tatars see their development within the state of Ukraine, and laws aimed at splitting it up are in no way in our interests. As for the mechanisms for protecting our language rights, the ones enshrined in the Constitution and existing legislation would be enough for us," he said in an interview.

Serhii Kvit, President of the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, also criticised the law. He described it as one that does not strike the right balance between developing and using the state language as a unifying factor in society.

"There is no doubt that the law, which contradicts the Constitution, will increase the political divide in Ukraine and destroy the foundations of Ukrainian statehood,"

Serhii Kvit said in a statement.

The regional councils of Odesa, Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, Zaporizhzhia and Dnipropetrovsk all granted Russian the status of a regional language after the law was passed. The city council of Kramatorsk also supported the introduction of the law but kept the Ukrainian language as the language of office administration. The authorities in Berehove, Zakarpattia region, granted Hungarian the status of a regional language, as 48 per cent of the town's population is of Hungarian origin.

In 2013, Vladimir Putin awarded Serhii Kivalov and Vadym Kolesnychenko the Pushkin Medal "for their contribution to the preservation and popularisation of the Russian language abroad". Vadym Kolesnychenko fled to Russia in 2014 after the Revolution of Dignity and the beginning of Russia's war against Ukraine. He received Russian citizenship. The Prosecutor General's Office of Ukraine suspects Vadym Kolesnychenko of high treason.

In 2018, the Constitutional Court of Ukraine declared the Kolesnychenko-Kivalov Law unconstitutional.

Society and the Ukrainian language

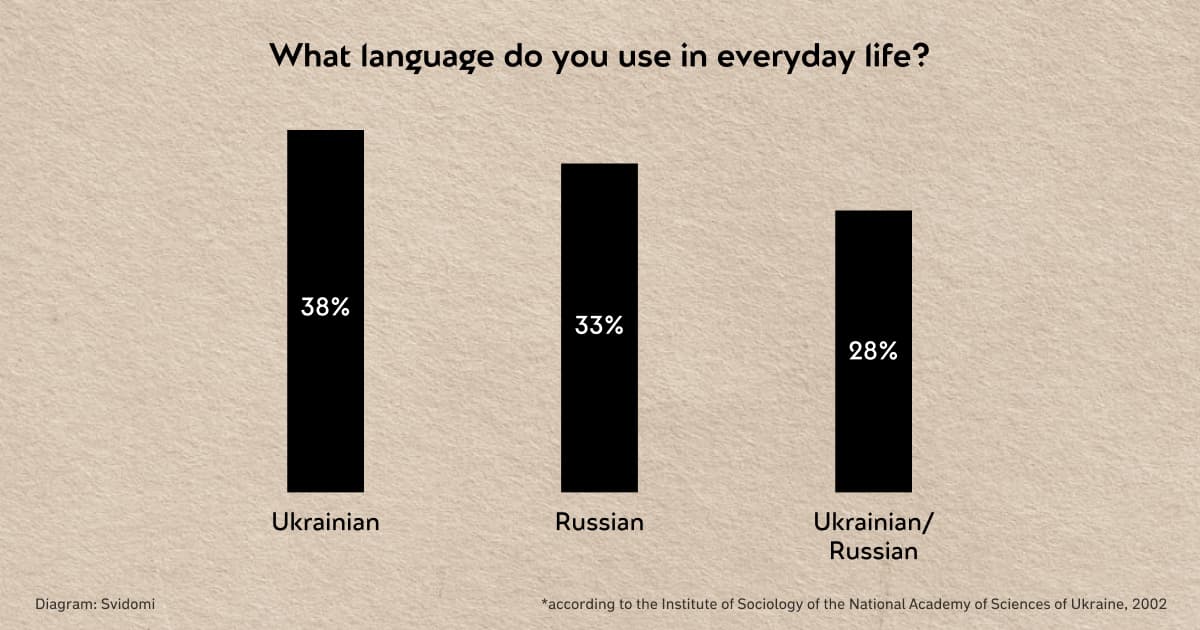

In 2001, according to the national census, more than 77 per cent considered themselves Ukrainians. 67% considered Ukrainian to be their native language, while 29% considered Russian to be their native language.

However, according to the Institute of Sociology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in 2002, only 38% of Ukrainians used Ukrainian in everyday life, 33% used Russian, and 28% spoke both languages. In public places (in transport, shops, etc. — ed.), Russian dominated — 35% of Ukrainians used it compared to 26% who used Ukrainian.

Feodosiia Kolesnyk, a philologist and head of the NGO "Feodosiia Kolesnyk Educational and European Centre", attributes society's attitude toward the Ukrainian language to the deliberate policy of the Soviet Union and Russia. That is why those who were aware of the process of Russification of Ukrainian society were the first to switch to Ukrainian.

"Language also brings us closer to ourselves and our nation. It is part of the general culture of the people, a continuation of who we are as Ukrainians. And those who begin to clearly understand themselves as Ukrainians see the transition to Ukrainian as something natural and necessary. After all, it becomes clear that without the language, you cannot fully feel like a Ukrainian,"

she says in a comment to Svidomi.

Despite the weak state language policy, more than a third of Ukrainians continued to use Ukrainian as a language of communication. In 2008, more than 42% of respondents to a survey conducted by the Institute of Sociology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine said they used Ukrainian in everyday life.

Doctor of Sociology Oleksandr Vyshniak, in his study of surveys conducted by the Institute of Sociology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in 2002-2008, concluded that more than half of Ukrainians believed that Ukrainian should be the only state language. Only one-third believed that Russian should be granted the "official" or "regional" language status.

"Despite the relatively high level of support for the status of Russian as an official or regional language, the highest level of support is for the current constitutional option — the status of Ukrainian as the sole state language with guarantees of the right to free communication and development in Russian and the languages of national minorities,"

concludes Oleksandr Vyshniak in his study.

The Revolution of Dignity and the Russian occupation of Crimea and parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions in 2014 affected Ukrainians' attitudes towards both the Ukrainian language and Russian. Research by the Prostir Svobody (Freedom Space) movement in 2014 showed some increase in the use of the Ukrainian language in everyday life. Forced Russification in the occupied territories had an impact on the use of Russian by Ukrainians, forcing them to switch to Ukrainian.

Despite the demand of society, the Russian language continued to dominate on television and radio, with the share of Ukrainian-language programmes on television at 30 per cent and the share of Ukrainian-language songs on radio at less than 5 per cent. However, in 2013, film distribution in Ukrainian was conducted only in Ukrainian.

Although Ukrainians were gradually abandoning the Russian language, "the link between Russification and the threat to Ukraine's state independence and the security of its citizens" was undeniable, according to the authors of the study by the Prostir Svobody movement. They also called on the Ukrainian authorities to develop and strengthen the Ukrainian language "in all spheres of public life".

Attitudes towards the Ukrainian language after the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian War

After the Revolution of Dignity and the outbreak of the Russo-Ukrainian War in 2014, politics and public attitudes towards the Ukrainian language changed. The Ukrainian authorities started introducing new laws to promote and protect the Ukrainian language. These laws included the Law on Radio Quotas, adopted in 2016, and the Law on Television Quotas, adopted in 2017.

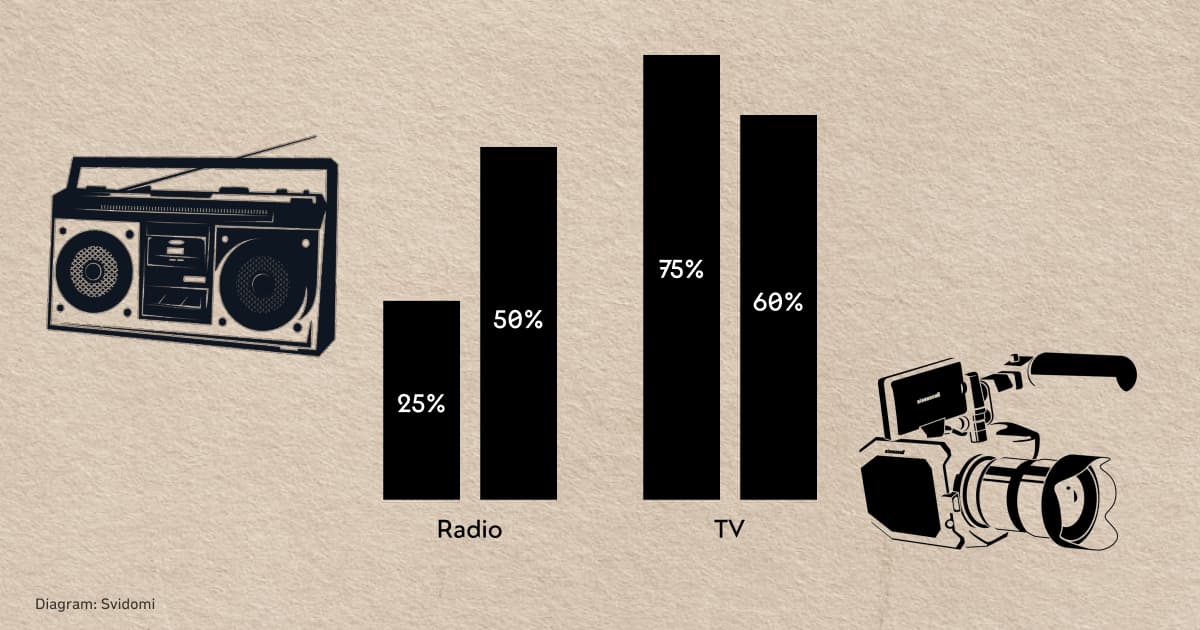

Under the new regulations, radio stations were required to broadcast at least 25% of their songs and at least 50% of their programmes in Ukrainian. National channels were required to broadcast at least 75% of their programmes in Ukrainian, and local channels — at least 60%.

Prior to the adoption of this law, the media regulated its language of broadcasting. According to the Teksty newspaper and the Prostir Svobody movement, the share of Ukrainian-language songs on the radio was only 5% in December 2014 and 10% in October, a month before the quota law came into effect. On television, in 2016, only 30% of programmes were in Ukrainian, over 34% were in Russian, and 35% of programmes were in both languages.

The Ukrainian media holding Inter Media Group criticised the law on television quotas. The media holding reported that it believes the law violates human rights, namely those of Ukrainians "for whom Russian is their mother tongue", and will "split Ukrainian society". According to the National Council on Television and Radio Broadcasting, the leading TV channel of the "Inter" media holding, as of the beginning of 2017, was broadcasting only 26% of its programmes in Ukrainian.

The "Ukraina" TV channel in 2017 (owned by Ukrainian billionaire Rinat Akhmetov, who transferred the licence to the state in 2022 — ed.) also had a 26% share of programmes in the Ukrainian language. However, the channel's management was preparing for the adoption of the law by increasing the share of Ukrainian on air.

"We understand that this (the increase of Ukrainian language on TV — ed.) is relevant. We have conducted our own audience research and studied the attitude towards the Ukrainian language product," Olena Sheremko, PR director of the Ukraina TV channel, told Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

In 2018, according to the data monitored by the Teksty newspaper and the Prostir Svobody movement, the Ukrainian language dominated radio and television. The share of Ukrainian-language songs increased to 54%, and Ukrainian-language programmes to over 64%. The share of Russian-language programmes dropped to 7%, with 28% of programmes broadcast in both languages.

In 2023, both quota laws were replaced by the Law on Media. The quotas for the Ukrainian language in this law were increased: on radio, the share of Ukrainian-language songs was increased to 40%, and on national television, the share of Ukrainian-language programmes on air was to be at least 90% from 2024.

In 2019, the Verkhovna Rada adopted the Law on Ensuring the Functioning of the Ukrainian Language as the State Language. This law replaced the Law on the Principles of State Language Policy, which was declared unconstitutional in 2018.

The new law was supposed to ensure the priority of the Ukrainian language in society and the public sphere: in public administration, media, education and science, culture, advertising and service provision. For example, the law required that the share of Ukrainian-language books on the market be at least 50% of all books. The law also regulated the use of the Ukrainian language on the Internet — online media registered in Ukraine are required to have a Ukrainian-language version unless they are published in the language of the indigenous peoples of Ukraine, English, or another official language of the European Union. The law did not regulate private communication.

The law also introduced the State Language Protection Commissioner position, or "Language Ombudsman". His or her duties include protecting the right of Ukrainian citizens to receive information and services in the state language in public life and removing obstacles and restrictions to the use of the state language.

In June 2019, MPs from the Opposition Bloc party (banned by a court decision in 2022 — ed.) submitted a petition to the Constitutional Court asking it to review the law and declare it "inconsistent with the Constitution of Ukraine". The MPs said that the law violated the rights of national minorities and contradicted the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.

"The Charter cannot abolish the compulsory use of the state language. This is stated in the Charter, in the law, as well as in the 1999 decision of the Ukrainian Constitutional Court and in the conclusions of the Venice Commission,"

said Mykola Kniazhytskyi, co-author of the law and a member of the People's Front faction.

In 2021, the Constitutional Court declared the law compliant with the Constitution.

Lesia Duda, PhD in Philology, associate professor at the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv and founder of the International Online School of Ukrainian Language and Culture "Tsvit", considers the adoption of the law to be the most progressive step by the Ukrainian authorities, but not the only one necessary to ensure language policy in Ukraine.

"The war has shown that the language issue is not only a matter of legislation. The psychological and emotional state of speakers, their support and accompaniment in the process of switching to Ukrainian, awareness of the processes and results of linguistic violence are also important segments of building an effective language policy. Unfortunately, this is something that was often neglected in society, so it "exploded" emotionally along with the war," Lesia Duda said in a comment to Svidomi.

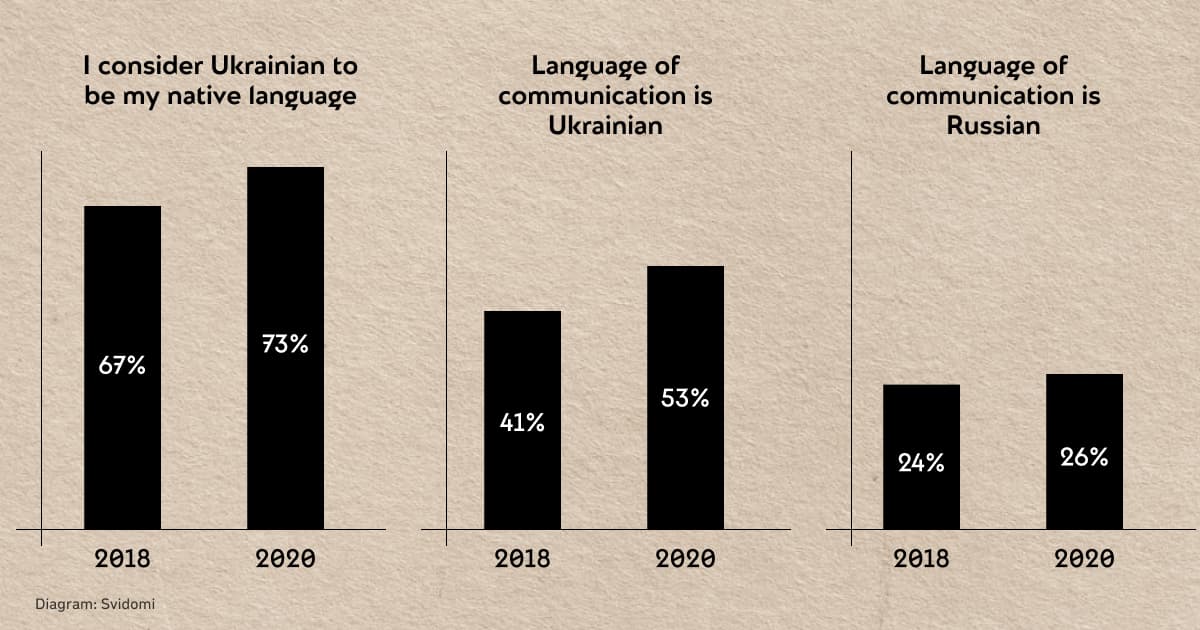

The Ukrainian language has also begun to assert itself in society as a language of communication. Studies by the Prostir Svobody movement show that in 2018, 67% of Ukrainians considered Ukrainian to be their mother tongue, and in 2020, the figure was already over 73%. In 2018, 41% of respondents said that Ukrainian was their language of communication, and in 2020 the figure was 53%. Russian is gradually losing popularity: 24% of Ukrainians spoke it in 2018, and 26% in 2020.

Feodosiia Kolesnyk believes that those Ukrainians who did not dare to switch to Ukrainian after the Revolution of Dignity were not ready to undermine their identity and change their habits.

"Today, language is a choice on the side of good and an indicator of Ukrainian identity. It's also a choice of breaking a lot of ties with the past, of giving up the culture we are used to. Many people are not yet ready to say goodbye to that life, not ready to accept a new reality in which Russian is an enemy language,"

says Feodosiia Kolesnyk in a comment to Svidomi.

After the start of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Russian language began to lose popularity among Ukrainians. In its 2022 study, the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology noted that 58% of respondents spoke mostly Ukrainian in everyday life, and only 7% spoke Russian. The vast majority of respondents believed that "Ukrainian should be the main language in all spheres of communication", and more than half said that "Russian is not important to them".

The author of the study, Doctor of Political Science Volodymyr Kulyk, said that such survey results indicated the intention to use Ukrainian rather than the actual usage and that "Ukrainians do not want Russian to remain a commonly understood language of public communication: this role is being taken over by Ukrainian". He noted the positive dynamics in the attitude of Ukrainians towards their own language, as well as the active position on the policy of strengthening the position of the Ukrainian language. This time, the Ukrainian government has already actively responded to this request from Ukrainian society.

Ivanna Kobeleieva, Ukrainian poet and co-founder of the NGO "Yedyni" and the "Teach in Ukrainian" initiative, says in a comment to Svidomy that the full-scale invasion has become an impetus for Ukrainians to switch to the Ukrainian language.

"We see a great demand for Ukrainian language courses and various language marathons. A lot of people have chosen the Ukrainian identity. They are switching to the Ukrainian language because they need a community where they feel comfortable switching to the Ukrainian language,"

she explains the reason for the transition to Ukrainian in everyday life.

Ivanna Kobeleieva also notes an increase in demand for the Ukrainian language. According to her, in 2021, about five thousand people took part in the Ukrainian language learning marathon of the NGO "Yedyni", dedicated to the 30th anniversary of independence. Now, this is the monthly number of participants in online Ukrainian language courses. People from the front-line areas are also taking part in the courses and in the language clubs.

"Ukrainian is the language of freedom and liberty, a powerful weapon of the Ukrainian people in the struggle for our independence and victory. Preserving our identity, reviving historical memory and strengthening the Ukrainian language is a matter of national security,"

said President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in his speech on the occasion of the Day of Ukrainian Writing and Language in 2022.