Four women and two months of occupation. The story of the family from Ruska Lozova

People lived under occupation for two months in the village of Ruska Lozova, 15 kilometres from Kharkiv. The Russians had occupied the village at the beginning of the full-scale invasion, and the Ukrainian military liberated it in May 2022.

About five thousand people lived in Ruska Lozova until February 24, 2022; in September 2023, there were almost no people on the streets. The houses are damaged by shells, and in some places, they have been destroyed completely.

I arrive in the village on a half-full intercity bus from Kharkiv, which runs every 30 minutes. Two dogs greet me at the bus stop, sniffing people, hoping to get something tasty.

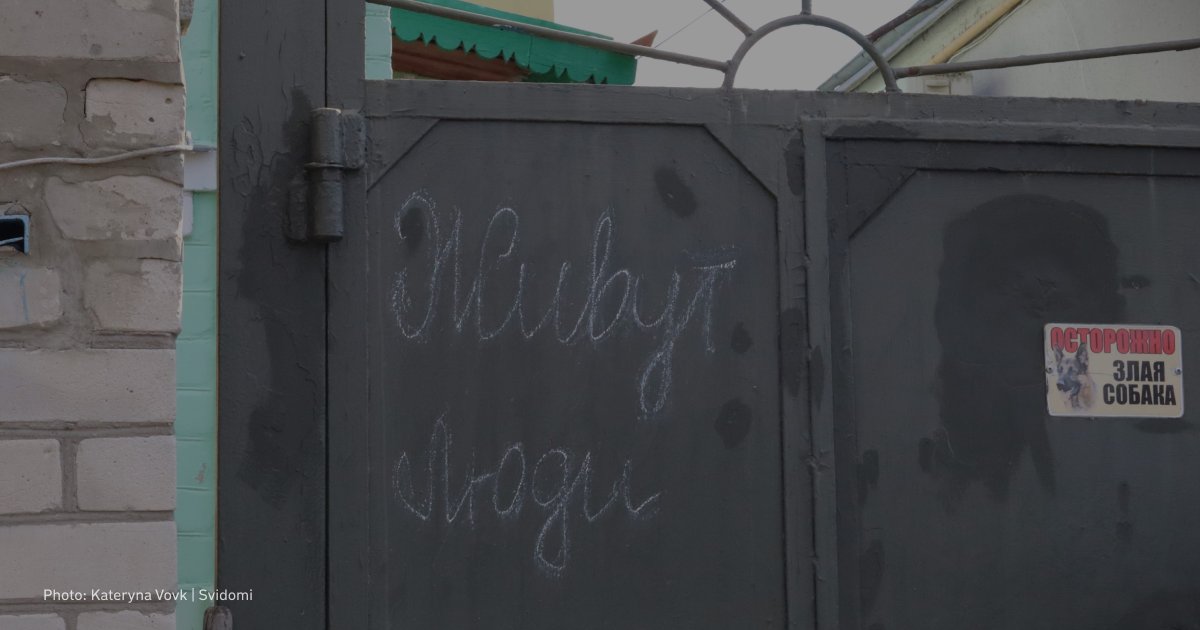

Local people are gradually returning to their homes in the village. You can see it in the mown grass in the yards, recently planted flowers, and conversations in the yards behind the fences marked "'People live here'. These words have been here since the occupation.

Power engineers have restored 100% of the power grid in Ruska Lozova, according to Oleh Syniehubov, the head of the Kharkiv Regional Military Administration.

There are no locals in the streets and lanes, but I hear women speaking and a dog barking in one of the houses. A woman in her 60s comes out of the yard. She lives with her mother and daughter. This is Liudmyla Bezpala, and she tells me about the beginning of the full-scale invasion, the occupation, evacuation, life without electricity and preparations for winter.

The house was constantly shaking. The beginning of the full-scale invasion and occupation

Three women live in a grey house behind a green gate on a street in Ruska Lozova. 64-year-old Liudmyla Bezpala meets me at the gate. She is dressed in a red blouse and white linen trousers. She immediately invites me into the yard, which is already filled with firewood and boxes of harvest from the garden. Her house was hardly damaged by Russian shelling: one window in one room had a broken pane, and the roof of the garage was damaged.

We pass through the yard and end up on the porch of the house where Grandma Nadiia is sitting. She is 96 and has lost her hearing, so she only nods in response to my 'Good afternoon'.

We enter a room filled with bags of clothes. Bags are on the sofas, floor, and chairs, even blocking the sun trying to get through the window. We want to switch on the light to see everything clearly, but there is no light. The electricity supply was cut off on February 24, 2022. Since then — until September 2023 — it has not been restored.

There was such a hum here on February 24. I was sleeping, and then I woke up and saw a fire and a rocket flying. It was flying towards us. My granddaughter Nastia started shaking. We did not know what to do. Nastia said that the war had started, and I said, 'What war, what are you talking about?

Liudmyla recalls, pointing to the window.

The family stayed in their house for the first two days of the full-scale invasion. They lived in constant fear with alarms, explosions and rocket attacks. However, they had no place to hide — almost all rooms in the house had windows.

It was especially scary because of the unknown: they didn't know what to expect, and they weren't sure they could protect themselves. That is why they decided to move to Nastia's friend's house, where a man, a shelter and other people were nearby. They felt quite safe together.

It was scary because we are four women. We didn't know what to expect or what we would have to defend ourselves against. They also had a basement and two walls,

says Liudmyla. She is interrupted by 40-year-old Olha, her daughter, who invites us to eat.

The hosts' kitchen is filled with the aroma of brewed coffee prepared on a gas stove. There are sweets, fruits, vegetables and candles on the table, providing light in the dark. The washed clothes hang on strings near the stove, and behind them is a wallpaper that is about to be torn off because of the dampness.

Olha has a friendly smile on her face and is dressed in a blue robe. But she looked different for the first three days of the full-scale invasion. She was in a state of hysteria, panic and excitement. She says almost no one in the family even ate during those days. She recalls that time seemed to stand still, and the understanding of what to do next disappeared.

First, Nastia offered to evacuate to Kharkiv and then to Poland, but Olha was against it. She didn't want to leave her mother and grandmother in Ruska Lozova, she was afraid they wouldn't be able to cope without her. She also believed that everything would end soon and they would return to their previous life.

The women remember the beginning of the occupation clearly: how the Russians walked the streets looking for weapons. Liudmyla had her husband's rifle, which she inherited when he died. She was lucky — she was not at home during the first Russian searches.

The second time, the Russians came under the guise of a 'sweep'. Armed soldiers burst into the women's house and began to turn everything upside down.

They looked everywhere: in cupboards, drawers, even in Nastia's make-up bag, where they found liquid soap with excise duty. They were surprised to find it and took it away. They went to Nadiia's grandmother's house. I was afraid they would do something to her. She said she was 95 and had had two strokes. They said she didn't look ill. Then they found a gun,

says Liudmyla.

They checked the house, the sheds, and the summer kitchen. She says the only places they didn't check were the toilet and chicken coop.

"I was scared, but we were lucky that they didn't touch us," she says.

Liudmyla and her mother, like many of the older generation in the village, need constant medication, and during the occupation, it was almost impossible to get it. Local men would risk their lives to cross the field to a Ukrainian checkpoint to order medicine.

Later, the Russians caught them. Olha says they are still alive but no longer deliver medicines.

When the planes were shooting, it wasn't so scary. It got scarier when the Ukrainian military started pushing them [the Russians] back. Sometimes, there would be a loud bang, and immediately, five buildings would start burning from the shelling. Then there were more and more explosions, and the house was constantly shaking,

Liudmyla recalls.

Evacuation and life in Russia

After three weeks of living with their neighbours, Olha and her daughter decided to evacuate, and Liudmyla and her mother returned to their home. The decision to leave came suddenly.

When they realised it wouldn't end tomorrow, they had to take Nastia and her friend out," says Olha. She didn't want the girls to live in danger and constant fear. She asked the neighbours who were staying there to look after her mother and grandmother.

"A neighbour's grandson came running to us on March 17 and said that the evacuation buses had arrived. We didn't even ask where we were going or who was doing the evacuation because we were so scared and stressed. We took the documents and money and went. We were taken to Lyptsi in the Kharkiv region and immediately told to go to the basement. I had already said goodbye to my life. I thought they were going to shoot us," says Olha.

A few hours later, other buses arrived and took the Ukrainians to Russian customs, where they crossed the border into Russia. They did not check the phones at the Russian border; just asked the Ukrainians what they had.

"I replied that the phone was useless because we had no electricity for three weeks. We don't know anything, the phones have been dead for a long time. There was no filtration then, so we were lucky to get through quickly," she recalls.

Olha fled with Nastia and her 16-year-old friend. They spent the first two days in Belgorod with all the other evacuees, then went to a friend's house in Moscow, where they stayed for about a month.

In Moscow, I had the feeling that I would never be able to go home again. The atmosphere was unpleasant, and I always felt that the sky was pressing down on my head. I wanted to return to Ukraine,

Olha recalls.

It was almost impossible to contact her family in Ruska Lozova because there was no connection. People had to go to the pasture (an area where cattle graze — ed.) to send messages or make calls. Later, there were rumours that if the Russians caught them with a phone, they would be shot on the spot, Liudmyla recalls.

"We didn't go there anymore. I was afraid. Nastia's friend, who lives nearby, used to go into the garden and catch the connection in the trees. That's how she sent information to Olha. At that time, many people had left, the village was quiet, and dogs were howling all the time. They were also shelling the village, and the houses were burning," says Liudmyla.

Thus, Liudmyla and her mother lived in complete obscurity, fear and occupation until the village was de-occupied on April 29, 2022. Then, an evacuation corridor was set up, and volunteers took them to Kharkiv. Staying in the village became increasingly difficult as there was no electricity, telephone service or medicine.

Before Ruska Lozova was liberated, Olha and Nastia had already returned to Ukraine. They could not live in Russia because of the constant thought of being far from home. Everything felt like a prison. On April 16, 2022, Olha and her daughter found tickets from Moscow to Poland.

The journey was easy because we knew we were going home. We packed sandwiches and patience and set off,

says Olha.

They travelled through Latvia. The journey took almost three days, and they only managed to return to Uman, Cherkasy region, on the evening of April 19. Later, their friend helped them to find temporary accommodation in Monastyryshche, Cherkasy region. They lived there until they returned to Ruska Lozova.

Bought firewood and candles — preparation for winter

Olha came to Ruska Lozova for the first time after the evacuation on October 20, 2022. She returned to her home for the first time on August 30, 2023. They realised that it was difficult to live apart in different regions and that it was better to return home and be together, Olha explains.

There is not much shelling now, but when we arrived, they 'fired salutes'. That was their way of greeting us,

Liudmyla recalls.

I met the family in early September, almost immediately after they returned. Although there are still some unpacked items in the house and there is no word on the restoration of electricity, they are happy to be together after more than a year of being separated.

Olha does not know whether the village has been demined, but she cleared her own garden with a rake when she had to plant vegetables.

There was no fear, only despair. I raked the area myself, and everything was fine. We needed to plant something, and there was no time to wait for a mine check,

she recalls.

The family also bought firewood and candles for the tables and cupboards. The gas supply was restored in December 2022. The women live on Olha's savings. Before the war, she worked in a factory making mattresses. Now, the factory is completely destroyed. Liudmyla and Nadiia also receive pensions. Nastia has moved to Kharkiv but sometimes comes back to visit.

Before the war, my goal was to buy a house. Now I won't be able to buy it, so we live on our savings. We live frugally, but it's enough to buy food. I might get a job in a few months, but I have to help my grandmother and mother now. The most important thing is that we are together, and that's all we need,

says Olha.

Today, 96-year-old Nadiia, who is experiencing the second war in her life, does not hear explosions or alarms, but she feels the care of her family. 64-year-old Liudmyla takes care of her mother, and 40-year-old Olha helps with the household. 19-year-old Nastia studies and works in Kharkiv.

These are four generations of women from Ruska Lozova who did not fear the months of occupation, the Russian military, the evacuation to an unknown destination and the risks of crossing the Russian border on their return to Ukraine. They were not divided by distance. The lack of basic living conditions did not become an obstacle to family reunification. Despite all the challenges, fears and difficulties, they remain united and strong in their home together.