Murders, repression and arrests. How did the Soviet authorities punish Ukrainian artists for protesting?

The Beatles released their single "Yesterday" in the US in September 1965, becoming one of the most popular in the world. Millions of people rejoiced and enjoyed the new melody. At Buckingham Palace, the musicians were awarded the highest honours of the UK — the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire.

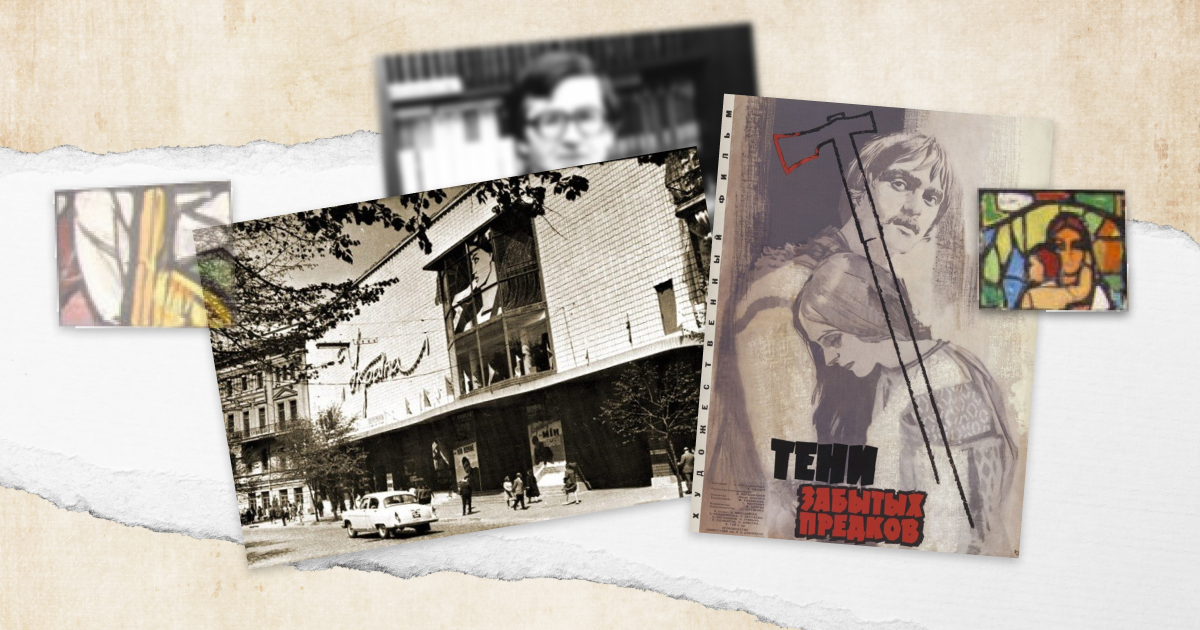

At the same time, the film Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, one of the 100 best films in the history of Ukrainian cinema, was presented in Ukraine. The screening was a way to talk about the repression of Ukrainian artists and to protest against the Soviet regime. Instead of receiving awards, the Ukrainians were fired and persecuted by the USSR State Security Committee.

However, the resistance movement against the USSR authorities was not limited to the film's premiere but manifested itself in many cultural spheres of Ukrainians, including art, tradition, and writing.

We tell about the last century's protests and refusal of the Ukrainian intelligentsia to obey Soviet ideology, for which they were repressed, persecuted and arrested.

"All those against tyranny, rise up!"

On September 4, 1965, the first public protest against the arrests of Ukrainian intelligentsia took place in the Cinema Ukraine in Kyiv. It happened during the screening of the film Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors by Serhii Paradzhanov. The action was initiated by literary critic Ivan Dziuba, politician Viacheslav Chornovil, poet and writer Vasyl Stus and film director Serhii Paradzhanov.

"What is Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors? It was a political act in addition to its outstanding aesthetic parameters. The film worked against the system of socialist realism. Even the focal point of the film, i.e. the fact that it was centred on a personality and entered the realm of folk, especially Ukrainian, life, was literally forbidden. The fact that it was made only in the Ukrainian version was a political challenge," said the cinematographer, Yurii Illienko.

Paradzhanov gave a speech before the film began. Ivan Dziuba came on stage after him and said: " Nowadays, Ukrainian intelligentsia — writers, poets, artists — are being arrested in Ukraine. A group of people have been arrested in Kyiv and Lviv. All those who are with us stand up to protest against the arrests."

The cinema director pushed the writer away from the microphone. They turned on a fire siren in the hall to silence the speakers. Viacheslav Chornovil supported Dziuba, shouting:

All those against tyranny, rise up!

Vasyl Stus stood up and called: "Everyone should protest: today they are capturing Ukrainians, tomorrow they will capture Jews, then Russians!" Serhii Paradzhanov joined the protesters: "I have resisted the translation of the Ukrainian text of the film into Russian for a long time." (Most Ukrainian films were dubbed in Russian then — ed.)

According to film critic Roman Korohodskyi: "Ivan Dziuba reports on the arrests of Ukrainian intelligentsia. The Gebeshchiks (representatives of the USSR State Security Committee, KGB — ed.) shout: "Provocation!" They turned on the loudspeakers to silence Dziuba. And t-hen Vasyl Stus and Slavko Chornovil appeared and called on the audience to stand up in protest. A few people stood up. I looked around — maybe 50-60 people were standing. The hall was full — 800 seats... But the fact of an open protest took place."

Dziuba was fired from his position as a consultant in the literary department of the Molod publishing house, and Chornovil was fired from the Moloda Hvardia newspaper. Stus was expelled from the postgraduate programme at the Institute of Literature and later arrested and held in the detention centre.

Ivan Dziuba was expelled from the Writers' Union of Ukraine and then detained and arrested. Paradzhanov's scripts were banned, and he was excluded from the film process. In 1973, he was imprisoned for five years and charged with a criminal offence.

Stained Glass Window 'Shevchenko. Mother'

In 1964, on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the birth of the poet and artist Taras Shevchenko, the administration of Kyiv University commissioned a stained glass window for the foyer of the Red Building. After approving the sketches, Alla Horska, Halyna Sevruk, Opanas Zalyvakha, Halyna Zubchenko, and Liudmyla Semykina began working on the layout. The artists were members of the Kyiv Creative Youth Club.

The artists created a layout — in the centre, they depicted Shevchenko, who hugs his mother, Ukraine, with one hand and holds Kobzar in the other. The lines complemented the image:

The poor and humble ones these will I glorify. Little, dumb and slaves are they, yet on guard about them will I set my Word.

They named the work Shevchenko. Mother.

The stained glass window was supposed to interpret the poetic tone, specifically the poet's righteous anger. After seeing the layout, the party leadership ordered a meeting to be held. Rector Ivan Shvets smashed the "ideologically harmful stained glass window" without waiting for the commission's conclusions.

The authors of the stained glass window were expelled from the Union of Artists of the Ukrainian SSR. Horska travelled to Moscow to rejoin the Union. The USSR State Security Committee took an interest in the artist. They installed listening devices in her apartment.

A wave of repression spread across Ukraine after that. Opanas Zalyvakha was accused of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda. The artist was sentenced to five years in a concentration camp in Mordovia, Russia.

In April 1968, Alla Horska signed the Letter of Protest of 139, where the figures of science and culture appealed to the top leadership of the USSR with a demand to stop the persecution, arrests and trials of artists. The artist was then expelled from the Union of Artists for the second time, and Horska was summoned for questioning.

Club of Creative Youth

The Club of Creative Youth was a centre of the Sixtiers in 1960-1964. Les Taniuk was the head of the club. Writers and poets Ivan Dziuba, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Ivan Svitlychnyi, Vasyl Symonenko, Stanislav Telniuk, and artists Alla Horska and her husband Viktor Zaretskyi were members of the club.

The members of the club initiated a meeting of nationally conscious anti-Soviet artists, holding several literary evenings, including an evening of the poet Vasyl Symonenko, an unauthorised commemoration of Lesia Ukrainka, and a meeting on the occasion of the reburial of Taras Shevchenko (the poet was moved from Kyiv to Kaniv in 1861 — ed.)

The artists Alla Horska, Liudmyla Semykina, and Viktor Zaretskyi discussed the unsatisfactory state of the Ukrainian language and culture in the Ukrainian SSR in March 1962. Other intelligentsia supported this discussion.

The club was subjected to greater persecution after Les Taniuk, Vasyl Symonenko, and Alla Horska appealed to the Kyiv City Council to publish the data on what the troops of the People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs of the USSR had done in Bykivnia (the place where the Soviet authorities secretly buried victims of Stalinist political repression who had been shot in Kyiv NKVD prisons — ed.) Eventually, it was closed in 1964.

What happened to the members? On November 28, 1970, Alla Horska went to visit her husband's father, Ivan Zaretskyi, in the town of Vasylkiv near Kyiv and never returned. A few days later, her body was found in the cellar of Zaretskyi's house. The cause of death was "blunt force trauma with limited impact area" — a hammer.

By that time, Ivan Zaretskyi was also dead. On November 29, his mutilated body was found on a railway track. Horska's friends did not doubt that it was a murder planned and carried out by the special services.

Ivan Svitlychnyi was arrested on September 1, 1965. On August 31, 1965, Svitlychnyi's apartment was searched. A few days later, the search was repeated, and only a week after Svitlychnyi's appeal to the KGB, Svitlychnyi's wife was officially informed of her husband's arrest.

Arrested Koliada or Operation Block

On January 12-14, 1972, the Ukrainian intelligentsia celebrated Christmas. Even though the Soviet government was against such gatherings, Vasyl Stus, Viacheslav Chornovil, and Ivan Svitlychnyi ignored the ban and sang carols in Lviv and Kyiv.

KGB officers in Kyiv and Lviv arrested 14 people, including Stus, Chornovil and Svitlychnyi. The KGB document contained lists of addresses which carolers planned to visit. The order read:

Nationalist-minded individuals intend to organise groups from among students of the Kyiv State University, Polytechnic Institute and creative intelligentsia to conduct carolling in Rusanivka, Darnytsia, Sviatoshyno, Akademmistechko, as well as in the centre of Kyiv.

Already on January 13, the KGB reported on the start of Operation Block, which was intended to "neutralise" people who could spread anti-Soviet politics, which, in particular, was considered to be carolling and singing.

Most arrested were sentenced for "anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda" and imprisoned for 5-7 years in strict regime camps and 3 years in exile.

After this case, Vasyl Stus was arrested for the first time. The writer was held in a detention centre for almost nine months. As a result, he was sentenced to 5 years in prison and 3 years in exile in camps in Magadan and Mordovia. Almost all of his manuscripts were destroyed in exile. He was released in 1979. However, he was later sentenced again to 10 years in a strict regime camp and 5 years in exile, where he died.

Ivan Svitlychnyi and Viacheslav Chornovil were also sentenced to 12 years in prison — 7 years in strict regime concentration camps and 5 years in exile.

While European culture was developing, Ukrainian culture was being persecuted, imprisoned and killed simply because it was Ukrainian.