Propaganda through cartoons during wars. How did Disney and other studios promote political ideas?

A cartoon is an image or series of images in different moods, situations and costumes. It's about children's hobbies and entertainment. It's about something carefree and good. But is that really how it works?

Read about Disney's involvement in World War II, Soviet propaganda during the USSR, the impact of cartoons on children and alternatives to children's content in this article.

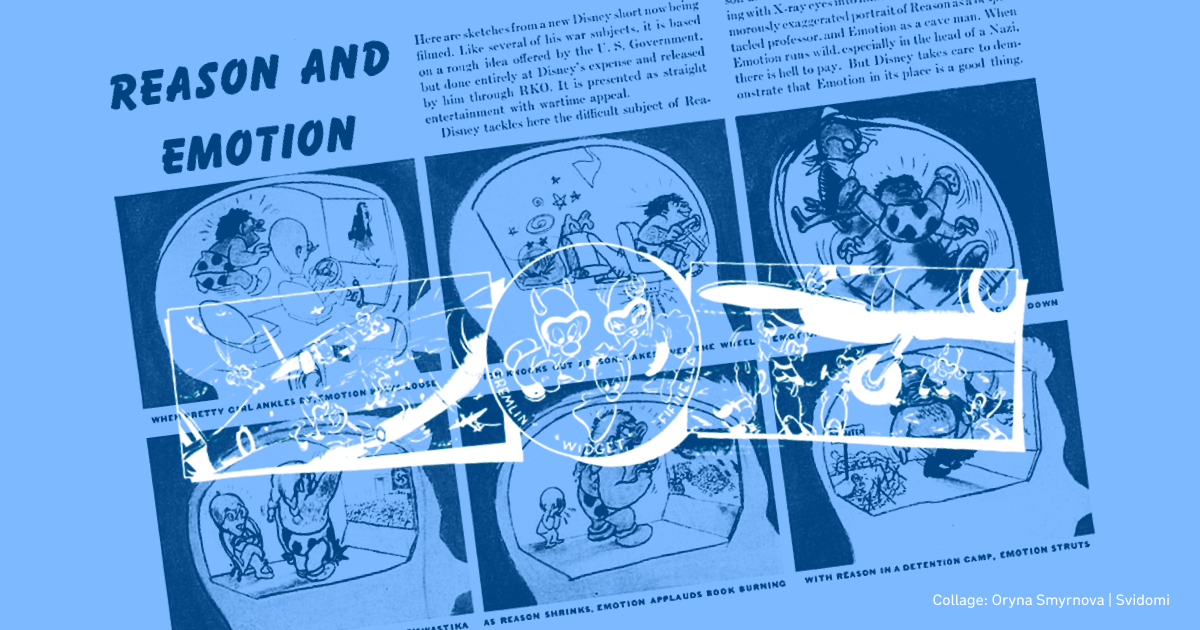

World War II and Disney

In the 1940s, as World War II began, the Disney Studio was facing bankruptcy. At the same time, US services approached the company with requests to create propaganda films against Japan (in 1941, the Japanese army attacked the US Navy base Pearl Harbor in Hawaii – ed.) and Germany (Hitler's invasion of European countries during World War II – ed.).

In the 1940s, studio founder Walt Disney signed a contract with the US Navy. It required Disney to produce twenty short cartoons about the war for the US government for $90,000 (more than a million dollars in 2023 – ed).

The Americans wanted to portray Japan, Germany and their leaders as manipulative and devoid of morals. During the Second World War, about 90% of the company's employees were involved in producing military movies.

For example, the movie Victory Through Air Power featured a scene in which a fictional rocket bomb destroyed a fortified German submarine force.

The animated film Education for Death tells the story of Hans, a boy born and raised in Nazi Germany, his upbringing in the Hitler Youth (youth organisation of the Nazi Party in Germany – ed.) and his marching off to war.

In 1942, the American animation studio Warner Bros. broadcast a short cartoon called The Ducktators (the title is a clever play on words, combining “duck” and “dictators” — ed.). The cartoon's main characters were Adolf Hitler, the Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini and the Japanese politician Hideki Tojo.

Propaganda in Soviet cartoons

Several generations in Ukraine grew up watching Soviet cartoons. A separate channel showed cartoons and children's fairy tale films called Detsky Mir (Children's World). "In the Soviet Union, there was no age-based labeling of cartoons. Cartoons were usually aimed at children, yet most of them were not. They were created for teenagers or adults," explains psychologist Kateryna Holzberg.

One theme of Soviet propaganda was the glorification of labor exploits. For example, the cartoon Pobedny Marshrut (Victory Route) tells about the implementation of the five-year plans, Stakhanov's feat (a miner who reportedly set records by mining 227 tonnes of coal in a single shift. His example was held up in newspapers and posters as a model for others to follow — ed.), and various Western so-called 'pests' who want to prevent the Soviet Union's 'grandiose plans'.

In 1971, a cartoon, filmed in the USSR, Pryhody Chervonykh Kravatok (The Adventure of Red Ties), depicted the Nazi occupiers as semi-comedic characters who tremble at a single drawing of the Kremlin in a school textbook.

There were also darker animation examples about fascists, such as Сkrypka pionera (The Pioneer's Violin). A fascist tankman is playing the harmonica and wants a Soviet pioneer (former Soviet organization for youth aged 9 to 14 — ed.) to play the violin with him. The boy refuses, and as a result, the fascist shoots the boy and destroys the violin.

A fully militarized cartoon is Malchish-Kibalchish (Boy-Kibalchish), about a boy from a village guarded by the Red (Soviet) Army. After all the current military personnel have left for the war started by the evil "bourgeoisie," the boy decides to become a soldier as well.

Later, he is captured by a thieving "bourgeois" who tries to ask him for military secrets, but he does not give them up and dies. He was buried as a little hero of the Soviet army. The cartoon also represents the beginning of the pioneer movement in the Soviet Union.

In addition to overtly politicized cartoons, the Soviet government disseminated less overt propaganda. For example, Three from Prostokvashino is a cartoon about a boy, Uncle Fyodor, who ran away from his parents with a cat to the village of Prostokvashino. The protagonist runs away because the family constantly quarrels and blames each other, demonstrating a toxic model of family relationships.

The film tolerates this behavior and makes running away from home seem natural. Children are shown that this particular model of relationships is acceptable when parents absolve themselves of responsibility and do not care that their son has run away somewhere.

The Soviet alternative to Disney's Winnie the Pooh features the protagonist Pooh as a rude character who likes to come to visit uninvited. The protagonist eats the gift he brings to his friend and knocks loudly on the door with his foot.

The cartoon shows that it's okay to come uninvited to your neighbors' houses and break down the door. This narrative promotes the approval of the Russian occupation of neighboring countries.

The cartoon Dunno on the Moon (Neznayka na lune) tells about a town of short people where everyone works as a single mechanism without rich people or money. It describes a utopian model of a communist society promoted in the USSR.

In this town, there lives Dunno, who does not work and is not a very positive character in the tale. Later, he goes to the Moon, which is a distorted allusion to Western countries, particularly the United States.

This is evidenced by the names of the lunar cities — Los Cabanos (wild boar), Los Poganos (scoundrel), and Los Svinos (pig). In contrast, the towns from which Dunno came have opposite names — Flower City, Sunny City, and Green City. The main message of the cartoon is that the West is evil, and life in Western countries is harmful to residents of the post-Soviet space.

"Cartoons, as part of propaganda, can impact the formation of a child's life principles and concepts, especially if used without critical thinking and proper support,"

explains child psychologist Marharyta Yehorenko in a comment to Svidomi.

Russian Masha and the Bear and The Three Bogatyrs

As of March 2024, the Ukrainian-language YouTube channel Masha and the Bear has over 14 million subscribers. But what do children get out of this cartoon?

In 2018, The Times published a story calling the Masha and the Bear cartoon Kremlin propaganda. Anthony Glees, professor and the security and intelligence expert, the University of Buckingham, said: "Masha is angry and very unpleasant. In one episode, the girl, dressed in a Soviet border guard's cap, protects a carrot patch from so-called 'invaders'”.

The Finnish newspaper Helsingin Sanomat cited Priit Hõbemägi, a lecturer at Tallinn University's School of Communication, as saying that the bear symbolizes Russia and is intended to replace the country's negative image with a positive one in children's minds.

He described the series as a "beautifully presented" part of an influence campaign dangerous to Estonia's national security. Similar concerns were voiced in Lithuania.

"Masha and the Bear is one of those cartoons that use elements of propaganda and entertainment content. It contains false ideas about the relationship between adults and children, irresponsibility, and disrespect. Formation of these moral values means lack of responsibility for one's actions or behavior that may not be acceptable, impact on development and social intelligence, as it contains many negative patterns of behavior that affect social adaptation and emotional development," the psychologist says.

The Three Bogatyrs (The Three Heroes) is a series of cartoons about three heroes imbued with the ideas of Russian imperialism. The main characters are Russians, although they come from Kyivan Rus. They call the Kyivan prince tsar-father. The symbolism in the cartoon depicts that historically, Kyiv has always been a part of Russia and belonged to Moscow.

There are symbols of Russian ideology used here: samovars (widely used in Russia to boil water for tea), matryoshka dolls (nesting dolls), sushki (small, crunchy, slightly sweet bread rings eaten as a dessert, usually with tea), and foreign things are supposed to be evil. Baba Yaga (wild old woman, the witch), one of the main antagonists in Russian folklore, is portrayed as a "dreamer of European life". She watches Europe and wants to live as they do, but the "valiant bogatyrs" drive her away from Kyiv.

"Children can see in the characters a reflection of their own characteristics and personality traits, which helps to form their own identity, but the influence of these idols can also be radically opposite," notes psychologist Marharyta Yegorenko.

The impact of cartoons on children

Cartoons play an essential role in children's lives, helping to shape their worldview, social skills and cultural perceptions, says child psychologist Marharyta Yehorenko.

Cartoons develop social skills by depicting complex social situations where characters face various challenges and conflicts.

"Children's content also influences the formation of values through the demonstration of moral lessons that can inspire children to do good deeds, empathy, and the perception of moral consciousness," says Marharyta Yehorenko.

The psychologist recommends that cartoons be divided into those that are useful and those that should not be watched. She also gives recommendations to parents on the choice of films:

- Before allowing your child to watch a cartoon, check its content, ratings, reviews and feedback to make sure it meets age-appropriate needs and standards;

- Consider your child's age when choosing a cartoon, as what is appropriate for one age may not be appropriate for another;

- Choose cartoons that teach positive moral lessons and help develop social, emotional, and cognitive skills;

- Avoid cartoons that reinforce negative gender, racial, or social stereotypes that promote violence or aggression;

- After viewing the cartoon, discuss the content with your child. Ask for impressions and opinions, whether the child understood the message of the cartoon, and what feelings the cartoon evoked;

- A time limit on content consumption should be mandatory. Provide a variety of entertainment and activities for the child's balanced development;

- Choose cartoons with positive characters and scripts that inspire the child to do good things.