Nuclear inheritance: why did Ukraine give up the world's third largest arsenal, and did it have other options?

Ольга Кацан

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, independent Ukraine inherited part of the former superpower's nuclear arsenal but voluntarily gave it up. The path to nuclear disarmament was a complex and lengthy geopolitical process influenced by a number of domestic and foreign policy factors. But the debate still rages today: was it the right path?

There are polar narratives in society on this issue: from arguments that the abandonment of nuclear weapons was a prerequisite for the establishment of Ukrainian statehood and a ticket to international recognition of the country to the fact that it was the biggest mistake, a crime and "ruin".

Read about the process of Ukraine's nuclear disarmament, what preceded it, and what conclusions we can draw today in the article for Svidomi by Olha Katsan, a journalist of the media development agency ABO.

This article was published as part of the special project 'The War Continues: A History of Ten Years of Resistance'.

When was the idea of abandoning nuclear weapons first mooted?

There were calls for the elimination of nuclear weapons, some of which were linked to the environmental movement even before the collapse of the USSR. In April 1986, the Chornobyl nuclear power plant disaster occurred. It was the first artificial disaster to be classified as the highest hazard level, seventh, on the International Nuclear Event Scale. It created a public fear of all things nuclear. Ukraine was saturated with the fear that the Chornobyl tragedy could happen again. Therefore, the first anti-nuclear rally took place in Kyiv a year later, where participants demanded the abandonment of nuclear power plants and nuclear weapons. As time went by, the number of rallies and demonstrations increased, and they took place in different cities of Ukraine (for example, in Netishyn, they protested against the completion of the Khmelnytskyi NPP). Archival photos and videos show that, in addition to the call "No to nuclear power", the protesters' placards also read "No to nuclear weapons".

The Green World Environmental Association also advocated declaring Ukraine a nuclear-free zone. It was stated in the programme adopted at the association's founding congress in October 1989, recalls international lawyer Volodymyr Vasylenko.

William Miller, the US ambassador to Ukraine from 1993 to 1998, recalls that Chornobyl was associated with danger to the extent that those around him perceived a diplomatic staff member's trip to Kyiv as dangerous. He suggests that Ukrainians "felt the need to eliminate nuclear weapons" because of Chornobyl.

The fear of the "peaceful atom" also seeped into the walls of the Ukrainian SSR's Verkhovna Rada's session hall. So much so that, in addition to considering a moratorium on the further construction of nuclear power plants in Ukraine, MPs suggested that nuclear weapons should be abandoned.

Borys Markov, Chief Economist of the Department of Labour and Social Affairs of the Executive Committee of the Kherson Regional Council of People's Deputies, first spoke publicly about the nuclear-free status at a meeting of the Verkhovna Rada on June 29, 1990: "We, who are marked with the Chornobyl star, are commanded to show the world an example of the first nuclear state to give up nuclear weapons by God Himself. That's why I propose to add the following section to this article: "As an expression of the people's will for peace, Ukraine proclaims a policy of permanent neutrality, non-participation in military and political blocs, renunciation of the use of force in international relations, and adherence to the three non-nuclear principles." At the time, the Armed Forces section of the Declaration of State Sovereignty was under discussion.

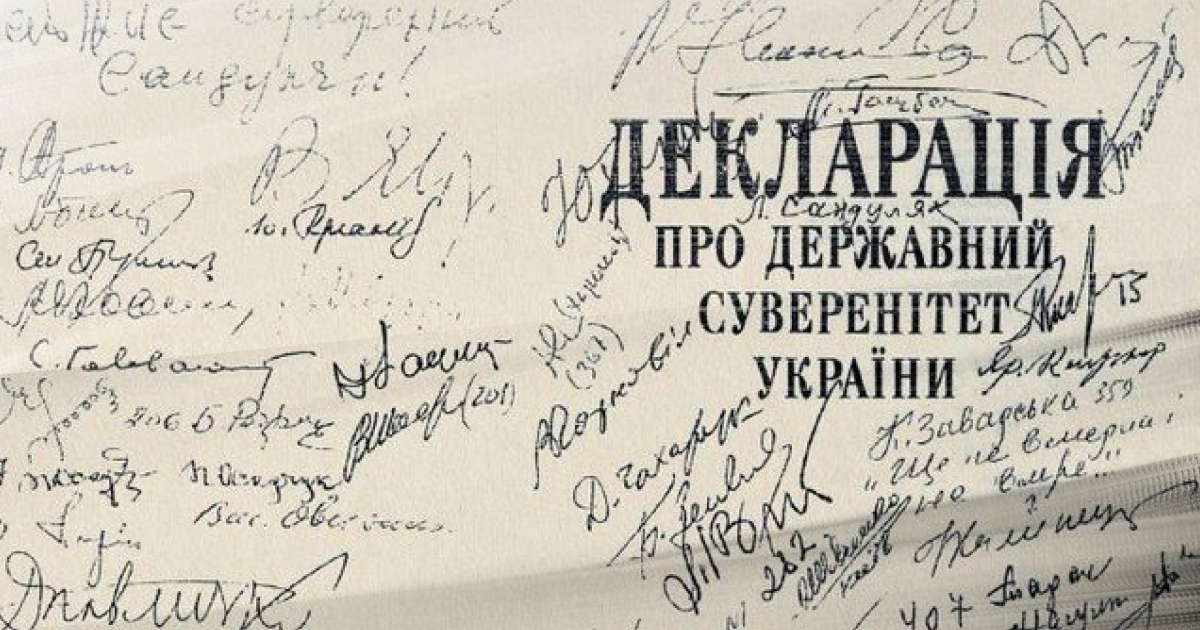

On July 16, 1990, the Verkhovna Rada of the Ukrainian SSR adopted this historic document. The Declaration of State Sovereignty enshrines three non-nuclear principles — non-production, non-proliferation and non-use of nuclear weapons — taken from the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.

The idea to include these principles in the document came from the People's Movement of Ukraine.

Volodymyr Vasylenko, who prepared the first draft of the Ukrainian Declaration of State Sovereignty, explained the motivation of the supporters of Ukraine's non-nuclear status by saying that this decision demonstrated "the desire to create conditions for broad international recognition of Ukraine's independent statehood and to avoid its international isolation". Ukraine was neither independent nor nuclear at that time (1990). To become an independent nuclear power, it would have had to take control of nuclear weapons in addition to voting for independence, which was impossible: Russia would never have agreed to such a scenario. In addition, the world knew almost nothing about Ukraine then, and its place on the world map had to be fought for.

The leaders of the Soviet republics often did not even know what military facilities were located on the republic's territory. The military, and especially the nuclear strategic component of the huge Soviet army, was concentrated in Moscow. The authors of the Declaration of State Sovereignty understood this as follows: if we fail to break these military ties with Moscow, with which we have virtually no business, then there will be no Ukrainian independence. That is, we will be kept in the Union by these military ties,

explains Mariana Budjeryn, Senior Research Associate at the Harvard Belfer Center's Project on Managing the Atom, author of "Inheriting the Bomb: The Collapse of the USSR and the Nuclear Disarmament of Ukraine".

Although there was a desire for independence in the Ukrainian SSR at the time, the US disapproved of such sentiments: the US administration did not want the Soviet Union to collapse, fearing, in particular, a repeat of the Yugoslav wars. So George H.W. Bush visited the USSR to persuade it not to rock the boat. He arrived in Kyiv on August 1, 1991, immediately after a summit with Mikhail Gorbachev in Moscow. He gave his Chicken Kyiv speech in the Verkhovna Rada, where he warned against separation from the Soviet metropolis.

The Nuclear Arms Reduction Treaty was signed in Moscow during Bush's visit. Both superstates were to reduce their arsenals and eliminate almost half of the carriers: missiles, aircraft, and the number of warheads assigned to these carriers.

A few weeks later, the Soviet Union collapsed, and Ukraine inherited part of the former superpower's nuclear arsenal.

What did Ukraine inherit?

In 1959, the Strategic Rocket Forces of the Soviet Union were created. They were responsible for strategic nuclear delivery vehicles:

- intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) deployed in silo-based launchers (there were also mobile launchers, for example, in Belarus, while Ukraine had only silo-based launchers);

- strategic aircraft with cruise missiles (armed with nuclear warheads);

- submarines with sea-launched ICBMs.

These three elements made up the "nuclear triad". However, there was no submarine component on Ukraine's territory.

Tactical nuclear weapons were not part of the Strategic Rocket Forces. A special department of the Ministry of Defence of the Soviet Union, the 12th Chief Directorate of the Ministry of Defence (12 GU MO), was in charge of them. It delivered this type of weapon to central storage facilities (objects "C", of which there were three in Ukraine): it was stored there and delivered from there to military units.

When the USSR collapsed, Ukraine deployed one of the five Strategic Rocket Forces — the 43rd Missile Army, headquartered in Vinnytsia.

At the time, Volodymyr Mykhtiuk, a colonel general, was its commander. Two divisions of strategic missile troops remained under the command of the army — the 19th in the Khmelnytskyi region and the 46th near the city of Pervomaisk (at the intersection of the Mykolaiv and Kirovohrad regions). You can see the latter with your own eyes — the Museum of Strategic Rocket Forces is now open there, and former missile specialists give tours.

Ukraine's "legacy" consisted of 176 intercontinental ballistic missile launchers with warheads, 25 Tu-95 MS strategic bombers, 19 Tu-160 supersonic strategic bombers, 1,080 nuclear air-to-ground cruise missiles and several hundred tactical nuclear weapons. The warheads contained nuclear fuel — highly enriched uranium and plutonium — for which Ukraine later demanded compensation.

However, the country could not fully control these weapons —- part of the arsenal, the facilities for their maintenance and the "nuclear briefcase" (a device that was the centre for authorisation, transmission of orders and codes necessary for launching strategic forces) remained in Russia. Various elements of the system were distributed among the former Soviet republics.

Nevertheless, Ukraine had considerable scientific and technical potential: Design Bureau Pivdenne, Pivdenmash and the Antonov plant, as well as Ukrainian scientists who had worked in the Soviet nuclear programme and had relevant knowledge of the operation and maintenance of the nuclear arsenal.

Retrospective: what preceded the Budapest Memorandum?

In 1968, the five nuclear powers (France, China, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and the United States) signed the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) to prevent the emergence of new nuclear powers worldwide.

Russia became the successor to the Soviet Union, taking on many of its debts and obligations. Ukraine, on the other hand, has not officially changed its disarmament course.

"When the CIS treaty was signed in Belovezhskaya Pushcha, one of the first articles stated that Soviet nuclear weapons would remain under a single control and command. Later, at the Almaty and Minsk meetings of the CIS, a decision was made according to which Russia assumed the responsibilities of the Soviet Union, was the successor to membership in the UN and the UN Security Council, and Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan would join the NPT as non-nuclear-weapon states," says Mariana Budjeryn.

In this nuclear puzzle, the interests of Russia and the United States coincided, making their proposals and demands. At the same time, Ukraine defended its interpretation of the requirements (demanding compensation for the nuclear elements contained in the warheads and security guarantees, which would be a real battle in diplomatic circles for several years). For several years, Ukrainian diplomats faced a ping-pong game of negotiations.

In October 1991, Ukraine adopted a non-nuclear status declaration. This document served as an assurance to the West that Ukraine would continue its disarmament course: the presence of former Soviet nuclear weapons on Ukrainian territory was qualified as temporary. Two months later, in December 1991, Ukraine signed the Commonwealth of Independent States Treaty on Strategic Forces. It stated that nuclear weapons deployed on the territory of Ukraine were under the control of the Joint Command of the Strategic Forces. They were to be dismantled by the end of 1994 and tactical weapons by July 1, 1992.

The Lisbon Protocol was signed on May 23, 1992. It legally recognised Ukraine as an equal partner in the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty. De facto, this document confirmed Ukraine's status as the owner of nuclear weapons located on its territory. It created the conditions for claiming compensation for nuclear materials and opened up the possibility of financial assistance for the destruction of nuclear weapons.

The principles of weapons disposal were set out in the controversial 1993 Massandra Accords. According to this document, Ukraine had to transfer nuclear warheads listed in the START I Treaty (which aimed at arms reduction, not total disarmament) to Russia within two years. However, the document that was handed out for signature contained the statement that Ukraine had to transfer all nuclear warheads within two years. Kravchuk's adviser, Anton Buteiko, noticed this during the negotiations. He added the phrase "in accordance with START I". Both sides should have put their initials next to the added phrase to show that they had agreed on what had been added to the document by hand. It was not done, so the Ukrainian and Russian delegations left with different ideas about what they had signed. Russia later denounced the document.

On November 18, 1993, the Verkhovna Rada ratified START I, but with significant reservations. By doing this, the government confirmed that it interpreted its obligations under the treaty as reductions rather than complete disarmament. It caused a scandal in the West.

On January 14, 1994, the Trilateral Statement was signed in Moscow: Russia made certain concessions to Ukraine, and the US increased its technical assistance. A few days later, the Verkhovna Rada lifted the START reservation, and Ukraine effectively gave up its Soviet nuclear weapons.

On November 16, 1994, Ukraine acceded to the NPT: it refused to produce nuclear weapons in the future, regardless of its nuclear past.

What happened in the period between the signing of these documents?

Ukraine was under pressure from both sides. The United States was afraid of nuclear proliferation in different countries. Russia was acting from the position of a powerful state.

As for our Western and Northern partners, their reaction to Ukraine's nuclear status was even clearer and more unequivocal. The phrase "nuclear weapons" popped up in their minds after the word "Ukraine" in the same constant manner as Pavlov's dog salivates after switching on a light bulb,

wrote Ukraine's first Minister of Foreign Affairs Anatolii Zlenko in his book Diplomacy and Politics.

There were fears in the Ukrainian political circles that Ukraine, having abandoned its intention to disarm, would become isolated and turn into a kind of North Korea. Serhii Omelianiuk wrote about this: "Moscow and Washington made it clear to President Leonid Kravchuk's Office and the Verkhovna Rada that the abandonment of nuclear weapons was a prerequisite for the development of relations with Ukraine. Thus, in November 1993, NATO threatened to withdraw Kyiv from the Partnership for Peace programme if it continued to block the process of nuclear disarmament."

Alongside the fierce diplomatic negotiations, there was an almost detective story about the disappearance of tactical nuclear weapons from Ukrainian storage facilities. When the irreversible process of the USSR's collapse began, the central Ministry of Defence In Moscow began transferring tactical weapons from the three republics to Russia. According to the Alma-Ata Protocol, Ukraine was supposed to hand over its tactical weapons by June 1992. But even before that deadline, Russia did so without the consent of the Ukrainian leadership. "It seems that even President Kravchuk was unaware of the whole process," says Kostenko. At the time, he was head of a temporary Verkhovna Rada investigative commission that was trying to find out how the tactical weapons had been exported.

At the request of one of the deputies, the commission received a document signed by the then Deputy Minister of Defence of Ukraine, which stated that "the decision was taken by the 15th Directorate of the USSR Ministry of Defence following the 1990 Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine,

he recalls.

At the end of February 1992, Ukraine announced that it would stop exporting tactical weapons. "The cessation was achieved by blocking the movement of trains at the border, although not much is known about the details," says Mariana Budjeryn. The authorities demanded that a mechanism be created to confirm that these warheads had actually been destroyed in Russia and not put on combat duty.

So Yurii Kostenko went to a facility in the northern Urals where tactical weapons were being dismantled to make sure the warheads were actually being destroyed. After seeing what he saw, he concluded that the fact that Ukraine supposedly controlled the process was fiction: the company flattens the casing, and the plutonium and uranium rods are sent to the company that produced them to be reused.

Initially, Russia categorically refused to consider compensation for tactical weapons. Later, diplomats managed to agree on compensation in the form of a billion-dollar write-off of part of the gas debt. It was recorded in a secret protocol to the Trilateral Statement. This document was never made public: the Russian leadership did not want to show the public that it had agreed.

On December 5, 1994, Ukraine, Russia, the United States and the United Kingdom signed the Memorandum on Security Assurances in connection with Ukraine's accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (this document is better known as the Budapest Memorandum), which will be the subject of intense debate after 2014. This memorandum is not a treaty: it has not been ratified by the parliaments of the signatory countries.

Ukraine lost its nuclear status on June 2, 1996, when the last nuclear warhead crossed the Ukrainian border.

What was the management of nuclear weapons, and could Ukraine have done it independently?

Discussions about whether Ukraine could have reconfigured its nuclear weapons management system and preserved its arsenal continue to this day.

The peculiarity of such destructive weapons is that they are created for deterrence, not for use on the battlefield. However, a "nuclear weapon" is a special system of devices that cannot be acquired, hidden in a safe, and left untouched until the time when it is necessary to frighten the enemy. It requires continuous maintenance.

First, the missiles that were produced and kept operational in Ukraine were aimed at the United States and had a range of 8-10 thousand kilometres. To deter Russia, we would need missiles with a shorter range. Ukraine could not produce them then because the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty was in force until 2017.

Second, the "nuclear briefcase" remained in Moscow. Theoretically, given the country's scientific and technical potential, Ukraine could have developed its own nuclear weapons and created a launch authorisation system for them.

Third, the system of targeting and controlling strategic missiles was also carried out using spacecraft, which at that time were the infrastructure of the Soviet Union. In other words, Ukraine, which has no spaceport, would have to build its own independent space infrastructure to control missiles.

Fourth, Ukraine did not have a complete nuclear fuel production cycle. Although the country mined its own uranium ore at Zhovti Vody, it lacked the following steps to produce fuel. These could have been created, as there was no shortage of scientists and knowledge, but money had to be invested in this business.

Fifth, there was a crisis and hyperinflation. Ukraine was dependent on financial support from abroad. Was society ready to tighten its belt even further in the "grey nineties" in order to build and maintain the infrastructure for nuclear weapons?

At the same time, in the mass consciousness of Ukrainians, no one was going to fight Russia (our neighbourhood was not perceived as a threat), let alone threaten it with nuclear weapons. After the collapse of the USSR, the idea of "brotherly nations" was popular. In addition, in 2013, the level of "love" for Russia was 50%, which began to decline after the annexation of Crimea and the occupation of Donbas.

There were also other issues relating to the storage of nuclear weapons. According to regulations, warheads are sent back to the manufacturer 10-12 years after production: they are disassembled, refuelled and reassembled. Every three years, the main part of the missile is removed to refill it with explosives that trigger the nuclear reaction. The warheads were sent to the city of Sarov in Russia for such manipulations, as Ukraine could not carry out such procedures at home.

What is the current assessment of the decision?

Volodymyr Vasylenko wrote that Ukraine's security sector has been negatively affected by 20 years of internal geopolitical uncertainty and the lost time that should have been used to build up the defence industry and powerful armed forces.

The main reason for the country's security problems should be sought not so much in the shortcomings of the Budapest Memorandum, but primarily in the government's inadequate security policy, or rather in its absence,

said the international lawyer.

Volodymyr Horbulin says in his book "No Right to Repent" that "the only, but significant, drawback of the Budapest Memorandum is that it is political, not legal. And this creates the conditions for the countries that are the guarantors of our security to interpret their responsibilities freely". Although Mr Volodymyr used these words to illustrate the situation on the Tuzla island 20 years after the document was signed, Ukrainians were convinced that the aggressor had its own interpretation of its obligations.

Four days before the full-scale Russian invasion, Volodymyr Zelenskyy gave a speech at the Munich Security Conference.

In his speech, he raised the issue of renouncing nuclear weapons:

Ukraine has received security guarantees for abandoning the world's third nuclear capability. We don't have that weapon. We also have no security. We also do not have part of the territory of our state that is larger in area than Switzerland, the Netherlands or Belgium. And most importantly — we don’t have millions of our citizens.

Then the President initiated consultations under the Budapest Memorandum for the fourth time: "If they do not happen again or their results do not guarantee security for our country, Ukraine will have every right to believe that the Budapest Memorandum is not working and all the package decisions of 1994 are in doubt," Zelenskyy said.

After the outbreak of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the abandonment of nuclear weapons was called the biggest mistake, and the media started talking about a return to nuclear status. But experts say this is impossible.

Yurii Kostenko, who led the Ukrainian delegation on nuclear disarmament issues in negotiations with Russia and was the head of a special parliamentary group to prepare ratification of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, believes that Ukraine has cheapened itself. He quotes figures: dismantling the Soviet nuclear infrastructure cost about $4-6 billion, while Ukraine's average annual budget in the early 1990s was only $6-8 billion.

"We should have received higher compensation from Russia, apart from not transferring weapons to it, but destroying nuclear weapons on the territory of Ukraine," he said in an interview with RFE/RL.

According to Kostenko, Ukraine had a unique opportunity to use its military potential and the issue of nuclear disarmament as a starting point for its development. The former minister is convinced this did not happen because the communist majority remained in power.

By August 1992, I had an absolutely clear understanding of the strategy for moving towards nuclear-free status. There was no question of timeframes. It was all about Ukraine's national interests. And this strategy would end when Ukraine became a full member of NATO, the European Union and the collective security system — then Russia would no longer threaten us, and therefore, we would no longer need such weapons and the costs required to maintain the nuclear potential,

says Kostenko.

"By August 1992, I had an absolutely clear understanding of the strategy for moving towards nuclear-free status. There was no question of timeframes. It was all about Ukraine's national interests," says Kostenko. "And this strategy would end when Ukraine became a full member of NATO, the European Union and the collective security system — then Russia would no longer threaten us, and therefore, we would no longer need such weapons and the costs required to maintain the nuclear potential".

He says that it was beneficial for Ukraine to move towards a non-nuclear status because it could not produce nuclear warheads and had the capacity to produce uranium, but it was worth disarming at another price. At the same time, Kostenko stresses that the idea of joining NATO, while the most attractive, was unrealistic at the time because of public opinion and the views of the authorities: "From the point of view of the mentality of the government at the time, talking about NATO membership in the Verkhovna Rada was like pouring petrol on yourself and burning yourself. For them, NATO was something terrible".

In April 2023, the 42nd President of the United States, Bill Clinton, said in an interview with the Irish channel RTÉ that he regretted convincing Ukraine to give up nuclear weapons.

Visible consequences

We do not know what would have happened if Ukraine had kept its nuclear weapons because we do not have a time machine or an extra supply of lives that would allow us to live in an alternative reality. So, we have to rely only on what we have experienced.

On the world map, the Ukraine of 1991, 2013, 2022, and 2024 was in a different position and had different powers of voice and influence. Therefore, it is irrelevant to evaluate the events of the nineties through the lens of the present. However, we must learn lessons from this experience.

By voluntarily giving up its nuclear weapons, Ukraine joined the civilised world as a "law-abiding" country, gained loyalty in the West and a chance for economic development. At the same time, it became defenceless - now one of the guarantors to which it gave its nuclear arsenal is trying to destroy us.

In 2014, Russia annexed Crimea and started a war in the east of Ukraine. The country that gave the security guarantees set out in the Budapest Memorandum has itself violated them, effectively denouncing the document it signed by its actions.

On March 5, 2014, the consultation mechanism of the Budapest Memorandum was activated, but Russia ignored the meeting of the signatories. Since then, the public space has been filled with an avalanche of reports about the "most ineffective piece of paper", accusations of short-sightedness or naivety among politicians, and accusations of foreign partners of leaving Ukraine alone.

Perhaps at the time of the signing of the Budapest Memorandum, there was no awareness that such a situation, i.e. Russia's invasion, could happen, so no sanctions were imposed for breach of obligations,

says Mariana Budjeryn.

"Russia has destroyed confidence in the guarantees and ruined the world order that was based on the agreements. Since February 24, 2022, it has been threatening Ukraine and its allies with nuclear weapons in an open manner.

The theory of nuclear deterrence works in the case of Ukraine because neither NATO nor any ally is directly intervening in the Russian war against Ukraine: a conventional clash between countries with nuclear weapons could escalate into nuclear war, so other countries would not fight on the Ukrainian side. At the same time, Ukraine is not protected by a nuclear umbrella, so there are many concerns in the media about the possible use of tactical nuclear weapons on Ukrainian territory.

The history of Ukraine's nuclear disarmament can serve as an argument for other countries to build up their nuclear capabilities. If the world was moving towards limiting nuclear weapons before Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, it may now be moving in the opposite direction.