(Not) million tenders. How can architectural heritage be restored without public funds, and why is it important?

There is no roof or windows, and the silence makes my skin crawl. I'm standing outside the Sanguszko Palace in the Khmelnytskyi region, west of Ukraine, built in the eighteenth century. Today, only parts of the facade remain.

No, this architectural monument did not get hit by a Russian missile — it was destroyed by time, and it has never been restored.

In addition to the passage of years, we have a new threat of destruction of cultural sites — the Russian-Ukrainian war. As a result of the full-scale invasion, 664 cultural heritage sites have been damaged or destroyed in Ukraine. This threat is frightening. However, was the destruction of castles and palaces due to the lack of restoration processes alarming?

Read about the state of architectural heritage sites, restoration tenders, their absence, alternatives for monument conservation and the importance of preserving historical monuments in this article.

Who is in charge of cultural heritage?

In Ukraine, there are about 170,000 immovable cultural heritage monuments on the State Register. Over 15,000 monuments of national and local significance are included in the State Register of Immovable (Tangible) Monuments of Ukraine, and the best examples of cultural and natural heritage are on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Among them:

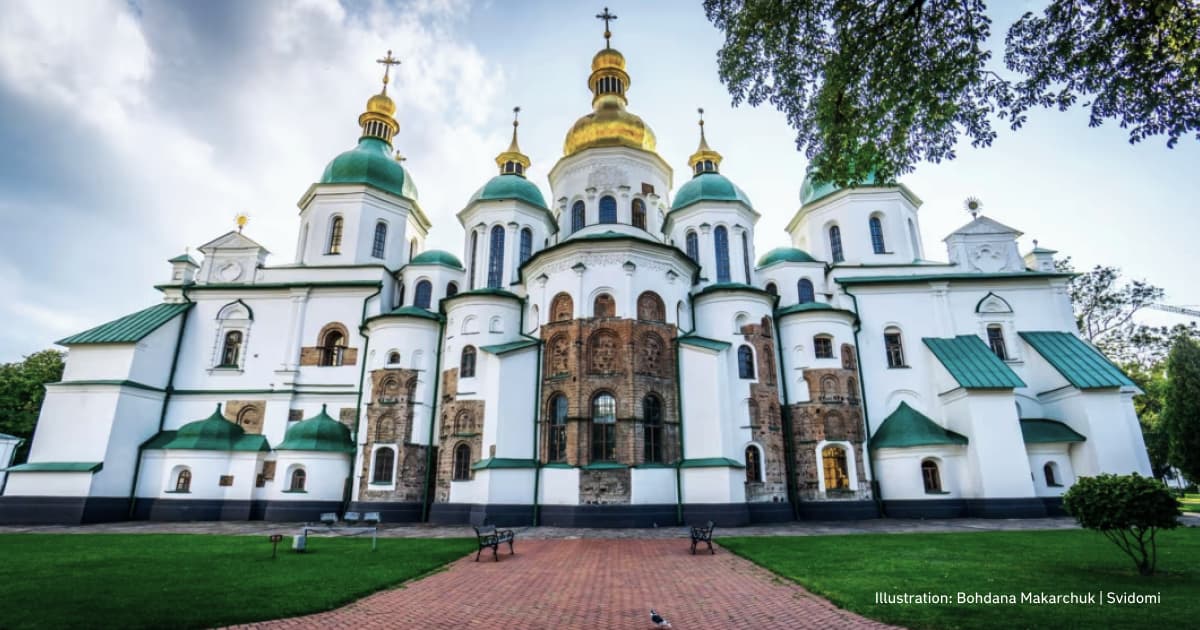

- St. Sophia's Cathedral and the adjacent monastery buildings, the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra;

- The ensemble of the historic centre of Lviv;

- Residence of Bukovyna and Dalmatia Metropolitans in Chernivtsi;

- The ancient city of Chersonesos Taurica in the temporarily occupied Sevastopol (Aqyar) in Crimea (Qırım);

- The historic centre of Odesa.

Heritage sites may be privately, communally or publicly owned. It is unclear what form of ownership most heritage sites have.

"The most effective form of ownership is communal. Communal enterprises are subject to the Law of Ukraine on the Protection of Cultural Heritage and are controlled by the local prosecutor's office. There is almost no control over private sites. Nothing can be done at state-owned sites because only the owner or his authorised body can be the manager of funds, the client of projects and their implementation," says Alisa Sviatyna, director of the Restoration and Technology Centre LLC, a restoration technologist.

Thus, local governments cannot spend money on object preservation in the municipality's territory because they are not their owners.

Archaeological monuments also present a challenge, as many sites are privately owned.

"Many private owners don't even know that their yard is on an archaeological site. Perhaps including the protected boundaries of archaeological and architectural monuments on the cadastral map would help improve understanding of where they are,"

says the restoration technologist.

The lack of proper documentation also affects the restoration process. Local governments on the cultural heritage sites' territory draw attention to their critical condition. In most cases, however, the problem is the same: a lack of essential documentation and accounting records.

"There are cases where sites are not properly registered according to the law. And before developing restoration projects, local governments must streamline the constitutive documents for such sites," explains Alisa Sviatyna.

Some objects still get restored

After regaining independence in 1991, several cultural heritage restorations were carried out. For example, the Transfiguration Monastery in Novhorod-Siverskyi, Chernihiv Region, in the north of Ukraine, was restored in 2004, St George's Church in Sedniv, Chernihiv Region, in 2008, and the Church of the Saviour at Berestove in Kyiv in 2019.

In 2021, the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine presented the Great Restoration Project. Its implementation was planned for 2021-2023 and would cover 150 of the most important architectural monuments needing restoration.

"This is the first project in the history of independent Ukraine to solve the problem of saving cultural monuments on a large scale. It includes emergency work, restoration and rehabilitation of sites across the country,"

wrote the Ex-Minister of Culture and Information Policy, Oleksandr Tkachenko.

In 2021, the state allocated UAH 711 million for 57 projects, including the Odesa Regional Philharmonic, the National Art Museum and the Tchaikovsky National Academy of Music in Kyiv, the church in Pidhirtsi in the Lviv region and the complex in Khortytsia in the Zaporizhzhia region.

However, the Center of Public Finance and Governance at the Kyiv School of Economics cites different figures. The analysts point out that the cost of the Great Restoration was UAH 275 million. Most of the complaints concern the contractors carrying out the work.

For example, the Zhovkva castle in the Lviv region, which borders Poland, was handled by Centre Complex. They signed a contract for UAH 6 million for additional emergency work. They signed the contract without a tender because of the alleged "need to work with the same contractor to ensure compatibility of work". However, the Centre Complex is on the Lviv City Council's list of unscrupulous contractors.

In 2022, a budget of three billion hryvnias was approved for the Great Restoration Programme, and another 100 new projects were planned. After 24 February 2022, when the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine began, most of the budget was used for military purposes, and the restoration came to a halt.

But is it on hold after two years of full-scale invasion?

Tenders or their absence

In 2023, the Prozorro e-procurement website registered a few tenders for restoration. The main request was for the restoration of walls or roofing.

In October 2023, a tender for the restoration of the roof, structural systems and gilding of the domes of the St Sophia of Kyiv National Reserve for UAH 79.4 million was registered. The Union of War Veterans appealed to the State Audit Service regarding the inappropriateness of financing works during the war.

"The army lacks weapons and equipment! Budget funds should be used primarily to finance the Defence Forces of Ukraine! This procurement is inappropriate, an inefficient, untimely, unjustified use of budget funds,"

the union said in a statement.

On December 20, 2023, there was a tender for the restoration of the house In Kyiv where the artists Mykhailo Vrubel (a Russian who lived in Kyiv – ed.), Volodymyr Orlovskyi (a Ukrainian artist – ed.) and Wilhelm Kotarbiński (a Polish-Ukrainian artist – ed.) lived. The cost of the tender for the house restoration is almost UAH 46 million. However, from the outside, the building does not look abandoned and destroyed, like dozens of others across Ukraine that have not yet been mentioned in any tender for restoration.

How many tenders were there to restore Pidhirtsi Castle in the Lviv region, one of the best examples in Europe of a combination of an imposing palace and bastion fortifications? There are only nine tenders on Prozorro that relate to the monument. The largest of them was for one million in 2016. However, even here, it is mentioned only in the list of six objects that need protection (the restoration is not specified – ed.).

What architectural monuments in Ukraine are under threat of extinction yet not mentioned in any tender for restoration?

Tereshchenko Palace in the Zhytomyr region, north of Ukraine, is a mansion built in 1851 by Count Adolf Grocholski, the owner of the village of Chervone. Philanthropist and landowner Mykola Tereshchenko later ennobled the complex. Today, the building is a wreck.

Chervonohorod Castle is a seventeenth-century defensive structure near the disappeared city of Chervonohorod in the Ternopil region, west of Ukraine. During the First World War, the palace was destroyed and never restored. Today, there are only two damaged towers.

The Sanguszko Palace, once a place for balls, is now an abandoned 18th-century palace complex in the centre of Iziaslav, Khmelnytskyi, west of Ukraine. The palace was built between 1754 and 1770 for Barbara Sanguszkowa (Polish poet – ed.) as a private residence and government centre of the Volyn possessions of the Sanguszko princes.

In May 2023, the Department of Culture and Tourism of Iziaslav City Council ordered services to create information products (creation of security contracts and accounting documentation) for the Sanguszko Palace for almost 25 Ukrainian hryvnias. It is the only tender related to the monument.

However, some tenders are still in force. For example, in August 2023, a UAH 1.4 million tender was registered to restore the Synagogue, a local architectural monument in Dubno, Rivne region, north-west of Ukraine. The first phase of the restoration has already been completed: the roof and brick vaulted walls have been repaired, and a drainage system and lightning protection system have been installed. A Jewish organisation from Frankfurt am Main provided funding for the roof repairs.

Restoration is not for the state budget. What are the alternatives?

In Europe, grant funding is actively used to restore architectural heritage. There is also the practice of transferring monuments to businesses when entrepreneurs use the premises for commercial projects while monitoring the condition of the cultural site.

"Transferring monuments to business is possible and necessary under clearly defined conditions. For example, if you own a monument in Germany, you have tax privileges but cannot replace door handles or carpentry elements. Protection agreements clearly define the relationship between private owners and the state and the penalties for non-compliance,"

says Alisa Sviatyna, a restoration technologist.

According to her, Ukraine also has the concept of security agreements, but there needs to be control over compliance with the terms.

"As for making a profit from cultural heritage sites, this mechanism depends on the site's owner and its use. The law allows for the adaptation of cultural heritage sites for modern use. Still, within the framework of restoration projects with maximum preservation of the site's authenticity," the expert says.

An example of architectural conservation is Promprylad.Renovation. It is an innovation centre based on an old factory (one of the oldest enterprises in the centre of Ivano-Frankivsk, west of Ukraine, built in 1905 – ed.) that works at the intersection of four areas: new economy and urbanism, contemporary art and education. The project has attracted more than USD 15 million in investment to create a commercial enterprise and preserve the building.

There is also an organisation in Ukraine called Mapa.Renovation. The team is focused on finding damaged architectural monuments in Kyiv, researching their history and ensuring the renovation of these buildings. They are putting all the objects on an interactive map so that everyone can learn more about the buildings needing protection.

"I believe that the funds for restoration available to local communities should be better used to streamline the documentation of monument protection, to monitor and conduct research to archive materials on monuments, which will allow them to be reproduced and the materials used for future design. Large sums of money would be better spent on purchasing equipment for the Ukrainian Armed Forces to speed up victory," says Alisa Sviatyna, a restoration technologist.

The importance of restoration

Preserving architectural heritage is not only about cultural and historical development. It is also about the economic aspect. A well-restored monument that functions successfully contributes to the growth of the city's and country's tourism potential.

"Cultural heritage sites are material evidence of our belonging to the Ukrainian nation. They are witnesses of the formation, development and rooting of Ukrainian culture, history and traditions. The destruction of cultural heritage is equivalent to the destruction of the nation's historical memory. The preservation of cultural heritage is the preservation of historical roots, which is the duty of Ukrainians,"

says Alisa Sviatyna, a restoration technologist.